Home > CR Reviews

Home > CR Reviews Parker: The Outfit

posted October 5, 2010

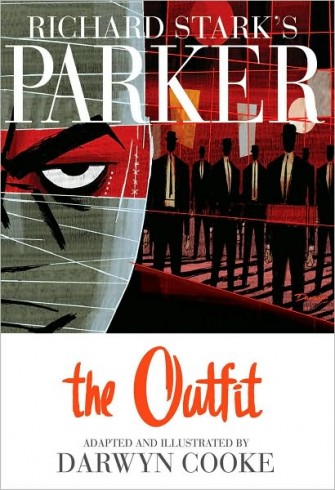

Parker: The Outfit

posted October 5, 2010

Creators:

Creators: Richard Stark, Darwyn Cooke

Publishing Information: IDW, hardcover, 160 pages, October 2010, $24.99

Ordering Numbers: 9781600107627 (ISBN13)

Massive digression: Peter Jackson's

Lord of The Rings movies changed the way I look at cross-media adaptations. The movie versions reduced Tolkien's languid sprawl of a prose trilogy into a strange mix of boys' adventure story and New Zealand travel porn. Gone were all the things I personally grooved to as a kid reading the books: people bursting into song at the drop of a hat, Tolkien's affecting reverence for immortality and exalted beings, and the underlying idea that the characters lived in a world that held close to its heart story and legend at the same time you were reading one of those stories as it unfolded. In their place movie audiences got a movie that darted back and forth between respectful treatment, rousing video-game violence, cool character moments and, lest we forget, low-comedy: dwarf-tossing, that strange Olympian Torch-bearing ignition orc, and the army of the oathbreakers as the SC Johnson Scrubbing Bubbles. If you had described that last group of scenes to me at 12 years old I would have shook my head and vowed never to see the movies. And yet the films worked for me -- they obviously worked for millions of people, but they also entertained me. They provided compensating virtues through what they lost not being prose, and suggested a different but still compelling set of ideas as to what those books were about, a view of them that ran parallel to my own interpretation without running roughshod over them.

It's that lesson that I take to Darwyn Cooke's adaptation of the

Parker series, which enters into its second volume this month with a book that blends elements of

The Man With The Getaway Face with a bigger chunk of

The Outfit, both key works in that series and the latter one of its most popular. I got the feeling about 100 pages into this second, equally handsome companion volume to the first that Cooke doesn't care if he's the right man for a measured, full, nuanced, and meticulously-detailed adaptation of this work or if there's another artist -- or their ghost -- that might provide a level of fealty and attention to verisimilitude that might please the reader for whom the works were strictly rooted in quotidian tableaux. I would guess having fun on the page to be a major concern, and pleasing anyone except himself and as much as it's possible his late collaborator is no longer something he's worried about -- if he ever was. Darwyn Cooke has doubled down on Darwyn Cooke, which if you think about it is sort of a Parker thing to do. If you see his style as impossibly pretty, the characters as overly attractive and the scene-setting as favoring surface elements of '60s design, and that this is inappropriate to your conception of what such an adaptation should be, you're as likely to be disappointed by the second book as you were the first.

For the rest of us, there are those compensating virtues and corresponding insights. I had a blast reading the story, a much more elaborate yet somehow less tedious version of the first book's heady confrontation between Parker's hyper-competence and ability to strictly compartmentalize versus The Outfit's attention to an abstract bottom line. For those of you that enjoyed the stylistic shift in the first book that came with its centerpiece flashback, you'll be glad to hear that Cooke works in many more variations of his standard style in

The Outfit, most obviously in a middle section devoted to a different graphic approach to each different job described. He also makes more of his standard approach, pulling at the extremes of it stylistically, most thrillingly in a household assault that's punctured by flashes of light and the clap of gunfire. Cooke also has a lot of fun with the identity theme, showing Parker in a variety of face-coverings and disguises, including that from his major plastic surgery. As in the first, Cooke contrasts how men conduct themselves in personal space with a sense of how they function publicly, which I think may be his most powerful contribution to our understanding of these stories. In this 1960s there are many more places to hide (Parker has an elaborate network of resources to aim at the Outfit, all of which seem burrowed into the fabric of American society) than to live (even the ideal of warmer climes and temporary dwellings are depicted as paper-thin refuges). The comic book version of Parker lets us see that expressed in a variety of visual cues that reinforce the effect negotiating these surroundings has on the lead character. Cooke also manages to wring a surprising amount of sympathy for a crime-fiction icon that famously resists it, bleeding his rational decision-making into a kind of personal ethos the lack of which he criticizes in others. At one point Cooke shows him mulling over a woman that didn't run away or suffer a breakdown when encountering the uglier secrets of his life. It's a striking image and a weird, off-key moment in a book full of both.