Home > CR Reviews

Home > CR Reviews Paying For It

posted April 10, 2011

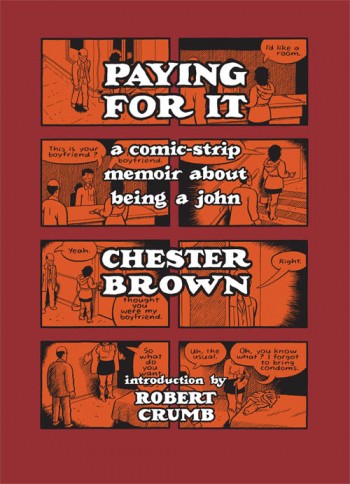

Paying For It

posted April 10, 2011

Creator:

Creator: Chester Brown

Publishing Information: Drawn And Quarterly, hardcover, 292 pages, May 2011, $24.95

Ordering Numbers: 9781770460485 (ISBN13), 1770460489 (ISBN10)

I felt myself at a disadvantage throughout the entire process of reading

Paying For It, Chester Brown's long-awaited graphic novel about his becoming a john and how that part of his life developed over a lengthy period of time. I have no interest in prostitutes, less interest than that in the issue of prostitution and sex work, and can muster only the tiniest bit of prurient intrigue for watching how a cartoonist of whom I'm a fan orients himself to the aforementioned. That's going to sound like a protestation, but I genuinely mean that I lack a fundamental interest in that specific subject matter. In his introduction, Robert Crumb describes in some detail a woman of his acquaintance revealing she did escort work and the personal shockwaves within that circle of friends that followed: that's the kind of thing that's unfathomable to me. I assume I know a woman or two in that position, and that I know a lot of men with experiences like Chester Brown's. What I don't know is a lot of people that have detailed their experiences and everything related to them to the extent Brown has here. The most fascinating sequence in

Paying For It for me didn't involve a single naked woman or the sensible peculiarities revealed by the veteran comic book maker as he unfurls the operational workings of such enterprises from the consumer's end. What I enjoyed most was a few panels where Brown tries to orient himself to the fact he'll soon move from the home of one-time lover and longtime friend Sook-Yin Lee. Buffeted by very understandable waves of grief, Brown gathers himself, pounces on a brief, inexplicable flash of happiness and pins it to the white board of his consciousness like an amateur entomologist. I've read that section four times now. It feels much more intimate than any time the cartoonist depicts himself in the sexual act, more revealing, even, than when Brown suggests we take a second look at his actions throughout this work for the implications of a surprising, final-act twist. The greatest strength of

Paying For It comes in its facilitation of these tiny, off-hand moments, less its ability to bring us the world in which Brown moves than the manner in which he processes what he sees once he gets there.

Off-key moments that yield worlds of meaning: that's the unique opportunity afforded by a cartoonist of Chester Brown's caliber. Brown has long been one of comics' most important and vital creators, and was maybe the last great cartoonist of his generation to roar into the consciousness of art comics readers like some sort of highway-jumping prairie fire, witnesses to the unique strengths of his work testifying to the devastating wonders of what was going on two or three hills over. He may be the last giant of the form to emerge where the scramble to encounter the work in question involved print testimony and a long car ride. Brown's talent allows him to depict anything in comics form --

any single thing -- and have each moment we spend in its company feel as remarkable as other cartoonists' giant space battles and heart-healing moments of emotional catharsis. One of the most exciting moments in comics in the last quarter century was discovering that Brown's comics could be as affecting and powerful depicting the mundane as they were bringing to life sentient penises, parachuting monsters and bristling, impatient messiahs. Any major work by Brown should be seen as a key, celebratory event in any comics-reading year in which one appears, and

Paying For It fits that bill without question.

Brown is a master of quiet insistence. Much of his work is about orienting the body, frequently depicted as full figures rather than partial or suggested ones, to oppressive outdoor spaces, insidious interior blacks and, no less dramatically, other people in the room. No cartoonist draws odder images that so quickly register as normal, and no one in the narrative arts makes such routinely inexplicable story decisions that one accepts for the authority with which they're introduced. Crumb notes that Brown portrays himself in

Paying For It as having almost no visible emotions: the face of his cartoon avatar is cut into an impassive mask. This seems stridently counter-intuitive, in that one would think a graphic novel about a controversial subject like prostitution might lean on the most humane, emotionally accessible depiction of its lead. Brown always makes his own way, though, and that way rarely provides comfort to the reader. There's a jittery undercurrent to Brown's work that shimmies to the surface at odd and unexpected times, a queasy energy unlike anything else in comics.

That noted, it's always enormously fun to read Brown, and

Paying For It proves no exception. There's little I can write that will ever do justice to the enormous visceral pleasure that can come with spending time in Brown's version of reality. One could argue that

Paying For It is a very good book about prostitution but an amazing work about adult friendships and turning 40. Brown makes a few folks just standing around talking look like a miracle, a scene in a café like a matter of great lifetime import; the cartoonist knows that many of the key instances in life come during conversations held while moving towards moments of much less significance. Whatever the comics equivalent of saying you'd watch a certain actor read a phone book might be, that's Chester Brown. He has become like noted influence Harold Gray in that you can fairly check out of the story at hand, sort of leave the details of the narrative at the side of the road, and settle into an extended appreciation of watching figures slice through a variety of environments in ways that affords them dignity and purpose above and beyond the details of their motivations and desires. There is something deeply comforting about a cartoonist so willing to play by a set of rules, even when they seem arbitrarily selected. In the tidal wave of different experiences presented between the cartoonist and prostitutes in

Paying For It that is the book's centerpiece -- a choice almost no other comics creator could have made without creating something that somehow lasciviously winked at the reader and become unreadable, even inhumane in the doing so -- Brown's ability to give each encounter narrative weight in some memorable way, even if he pushes through his depiction of that encounter very quickly, makes us trust him more as an advocate for both those experiences' mundane qualities and their transformational effect on the cartoonist. Sex may never be all the way a normal experience for people; yet if everything's as strange as it is in a Chester Brown comic, then maybe nothing's all that outside of consideration when it comes to open consideration, processing what it means, accepting what other people value in specific permutation that's offered to them.

The problem with having a disinterest in the general subject matter that informs

Paying For It isn't that prior knowledge and passion is any sort of prerequisite for enjoying art on a topic -- something even less true with Brown's comics -- but that in this particular case Chester Brown seems passionately interested and invested in the issues he raises and one may eventually feel left behind.

Paying For It is far from over when the cartoonist has his last, enlightening, words-and-picture discussion of his personal experiences with one of his close friends. In a manner familiar to those that have experienced past works of extended inquiry by Brown,

Paying For It offers up pages upon pages of appendices and notes, observations both personal and derived from key works encountered during research. These pages make up a significant percentage of the overall work, and I think any appraisal of the book has to engage what they say and how they say it. Working together, the notes and the comics push

Paying For It past an extended march through Brown's personal story and into a work of advocacy concerning many of the issues involved. I think this may have been done to the work's overall detriment.

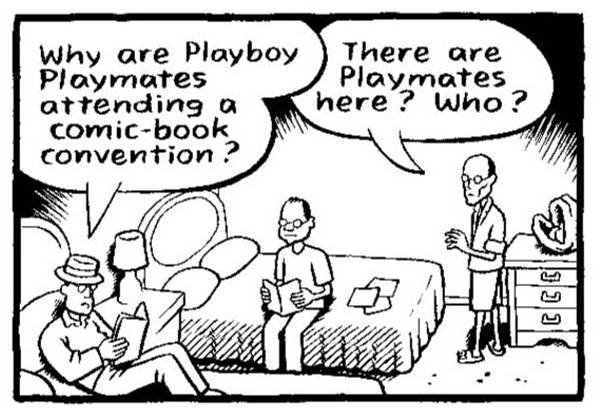

Brown is unapologetic to the threshold of argumentative passion -- or whatever Brown's dispassionate yet invested equivalent might be -- on these matters. It's clear that he's thought about them a great deal. There are revealed any number of fun, pleasurable and insightful elements to the supplementary material, from Crumb's opening salvo to the photo of Brown that caps things off. A significant amount of humor is brought to bear throughout, particularly in some tiny drawings into which Brown places arguments with which he doesn't agree. Brown is such an idiosyncratic cartoonist that his notes and commentaries delight through off-hand descriptions of narrative choices that no other cartoonist on earth would have made; such curt, matter-of-fact declarations duplicate the unsettled energy found in the work. Even an off-hand comment like how he chooses to portray Sook-Yin Lee's hair in one scene can set the reader's mind racing, or a description of whose participation he chose to drop from a discussion. Seth enters into the work as an authorial voice, and his is a welcome, bracing, solicitous presence. There's one set of notes that informs the comics narrative a great deal, about a certain burden Brown felt in his encounters with attractive women until he started seeing prostitutes. It may be the key to understanding the work. As is the case with similar scenes in the comic, it's as much the way that Brown engages that topic, for instance his certainty that most people will understand exactly what he's talking about, that's as informative as the confessional element itself.

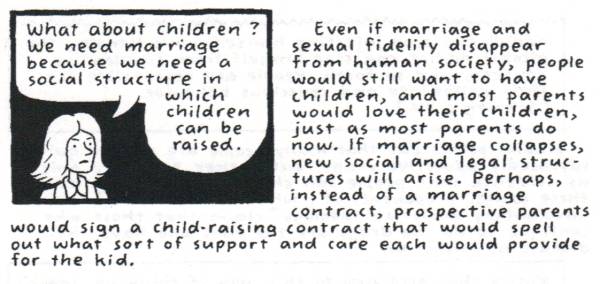

None of these positive qualities makes it any easier to accept some of the underlying arguments. That wider political and cultural issues are engaged in the first place never feels like a necessity. A lot of what Brown declares in the appendices seems derived from boilerplate political and moral theory the cartoonist may take as self-evident (a libertarian conception of personal property, for instance), while readers may not see things exactly that way or at least may wish to object to a point here or there. These ideas are then filtered through a personal set of circumstances that in their usage here comes perilously close to suggesting Brown's situation as portrayed is a universal one. When

Paying For It functions as a comics-format documentary about how Brown's way of moving through the world is improved by his employing prostitutes, it accrues effectiveness in a variety of ways. We like Brown, or at least come to respect the unadorned honesty with which he describes his personal journey, the way his worries and fears are resolved. As much as he seems to have benefited from his current choices, we celebrate that he was able to secure these things in his life. It's hard not to at least be sympathetic to those choices coming Brown's way without penalty or stigma, that current law may needlessly restrict a range of human experiences that includes Brown's.

This is a far cry from what comes through in the essays: that Brown's orientations might somehow be the basis for policy and cultural change, that all stigma is correlative, that the removal of cultural discrimination afforded paid sex is the difference between the world we live now and a world that functions a bit more like Chester Brown. When the cartoonist moves away from his own experiences and into broader proclamations about the nature of romantic love and assertions that more frequent monetary remuneration in sexual relationships will somehow ease relationships between men and women, it's hard to engage with what he's saying beyond being certain he means it. To put it more directly, even for someone not invested in the general subject matter, many of the broader arguments fail to convince. That they represent issues that can be argued, even passionately so, doesn't seem all that remarkable an endorsement in the Age Of The Internet. Give me scenes like the one where Brown argues with Seth over the issues, seething and impatient with Seth's answers and his own, desperate and human in wanting to make and win such discussions, over any number of facile dissections of each argument's actual merits. Within the context of a personal narrative, seeing Brown dismiss the possibility of abuses as things he doesn't himself see has a revealing, human quality; pushing past such arguments in a more standard mini-essay on the issue itself seems way more problematic.

Chester Brown remains now and forever a magnificent cartoonist, and in

Paying For It his comics should make all sorts of readers from all sorts of points of view consider arguments they may never have given the time of day otherwise. Part of me wishes that things have ended there; another part feels churlish in saying so.