Home > Bart Beaty's Conversational Euro-Comics

Home > Bart Beaty's Conversational Euro-Comics Conversational Euro-Comics: Barty Beaty On Olivier Schrauwen

posted March 11, 2011

Conversational Euro-Comics: Barty Beaty On Olivier Schrauwen

posted March 11, 2011

By Bart Beaty

Olivier Schrauwen

By Bart Beaty

Olivier Schrauwen is not the first Belgian cartoonist that I would have pegged for success in the United States, but I'm certainly not going to complain about the opportunities that he is receiving. Since the publication of his book

My Boy in English translation, he has published short pieces in

Mome and elsewhere, generating a solid buzz for his idiosyncratic take on human disconnectedness. His new book,

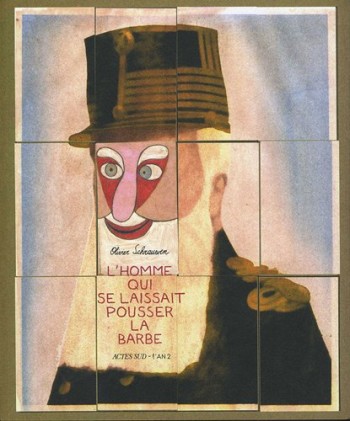

L'Homme qui se laissait pousser la barbe (Actes Sud/L'An 02) collects a number of short works that have been anthologized around the world, and was nominated for a prize at this year's

Angouleme Festival. It will be published later this year in English as

The Man Who Grew His Beard by

Fantagraphics.

Schrauwen's appearance in English seems to me a victory for the wing of the comics world that is most interested in graphic inventiveness. From

Kramers Ergot to

The Ganzfeld, from the books released by

Highwater to

PictureBox, the past decade in American cartooning has seen a turn, however limited, towards graphic innovation. Often eschewing the novelistic turn in the newly-minted graphic novel movement, a new generation of cartoonists has aligned themselves more closely with contemporary art practices than with existing narrative traditions. Schrauwen, whose stories are incredibly slight but impeccably rendered, is one of the stars of this tendency.

L'Homme is a collection of seven short pieces that can be read very quickly or studied for days. The whole book coheres less well than

My Boy, and it reads as a series of short stories that share thematic interests. To my mind, the best works are "Le Devoir" and "La Grotte." Both of these take as their subject the act of artistic creation. In "Le Devoir," a man in an art class is given the assignment of crafting a narrative image involving a cat, a mouse, a man, and some common objects. Allowing his imagination to play out various scenarios, he is driven almost to madness. In "La Grotte," the act of drawing is given religious, magical and mystical powers. The frantic blue and yellow coloring in "La Grotte" gives the work, the least structured of the book, tremendous power. Similarly, coloring in "Le Devoir" gives the work its shape. All of the pieces in the book seem to be well thought out, with only "Le Chateau" not really connecting with me.

Other pieces in the book return to the ground covered in

My Boy. The self-consciously ironic excavation of outmoded visual styles can be found in the titular story, as well as in the deeply alienated opening tale, "Congo Chromo," a wordless take on Belgium's colonial past in Africa. "L'Imaginiste." in which fantasy and contemporary reality meet is suggestive, perhaps, of a new direction for the artist, and one that would be quite fascinating should he choose to pursue it.

Overall, it seems to me that we will look back someday and think that

L'Homme is not the great Olivier Schrauwen book, but that it was the one that first pointed to the greatness that seems inevitable from a creative talent as innovative as he is.

*****

*

The Man Who Grew His Beard, Olivier Schrauwen, Fantagraphics, softcover, 112 pages, 9781606994467, August 2011, $19.99

*****

To learn more about Dr. Beaty, or to contact him,

try here.

Those interested in buying comics talked about in Bart Beaty's articles might try

here.

*****

*****

*****