December 27, 2012

CR Holiday Interview #9—Carol Tyler

CR Holiday Interview #9—Carol Tyler

*****

Carol Tyler

Carol Tyler is one of our great cartoonists. This year saw the publication of

the third and final book in her You'll Never Know series, about her relationship to her father and the lingering effect his time in World War 2 had on his life and that of his family. Tyler has a wonderful eye for color, a penchant for off-beat narrative structures and an underrated way with a tossed-off line. Her books would be compelling solely for the snapshot they provide into the life of a working artist, or for just getting down on paper that specific way that nature presents itself in the American midwest. I love talking to her. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: You've lived with these books for a very long time. How did it feel to get some closure on this work?

CAROL TYLER: It was obviously a relief. But... during the last year of getting the book done, it was impossible circumstances. I had to finish the book by May. I wanted to get it done sooner, but the soonest I could get it done was May. I'm sure you've heard, as I was finishing up the last half of the book in the summer: it started with having to put the dog down, our 16-year-old dog. Then my mom had to go to the doctor. She ended up in a hospital, ended up in a nursing home, ended up in a coma -- this is all over a period of months -- and my sister who was helping me keep it together, we're the ones that are close to our parents physically here,

she started to feel sick in October. It turned out she had stage three and a half, four cancer, ovarian cancer. So I literally... and my dad fell, and all of this stuff.

I literally had to take the artwork -- they live four hours from me -- I had to take the artwork with me and there were days when the artwork would appear at the bedside of my Mom, at the nursing home, my sister at her hospital in recovery, the

VA where dad was and then back to staying at my parents' house. I brought pencils, ink, everything. I couldn't not work, because I had to get the book done! It was madness.

I was able to show my Mom the pages penciled. Before she passed away she saw the work. It made her cry. She said, "This is very good." And it was just so hard to do. There were times when I had to rush over there and came back, and I didn't take the work with me. It was so intense what happened, and I would come back to my drawing board here and I would sit here and feel so calm and comfortable to be at the drawing table, away from the intensity of running around. I put that intensity into the back part of the book.

SPURGEON: As I recall, you've always been one to carve out time for your work. I think "The Hannah Story" was done when you were between jobs, and had specific time to do that story then. This sounds like a completely different working experience, with the work forced upon you in a way that maybe it wasn't in the past.

TYLER: It's been like, "Gotta do the book." "Back to the book." My world was centered around sitting down, doing some more pages, "I'll be inking tonight," for so many years. I made a sign and put it above the table. You know how the dollar bill has the eyeball icon on the pyramid? I made something goofy like that with ink and it said, "I worship the God of being done." [laughter] My work style is such that I just don't write a script, and then sit down -- "Oh, I'm on page 36 now." Although I did have a system, a systematic approach. I did have a lot of order in doing the book. But yes, it was different than how I had had to do it in the past, with raising a child and kind of doing the household thing.

I set out to do this task. I jumped in. I had to find the story. I knew intuitively what it was I wanted to do. As it became... at first I just threw a bunch of stuff out there to help me find, then it became clear how the story needed to be shaped. I knew what the ending was going to be. Pretty close to the ending, although not exactly. I knew the feeling of the climax, the ending. For example, I knew I wanted to talk about Dad's fortitude in having cancer and how that was something I've admired about him. Even though he was impossible. I did write that story a couple of years ago, but it didn't fit into the took until later. There were little pieces and parts like that. I didn't do it in sequence, but I did it thematically. Then I had to, you know, sit there and try to... before book one came out, I knew the general overview. But from 2004 to 2009, when the first book was published, I did do chunks and bits, chapters -- almost like back in the day, with

Weirdo, when I would do like one-pagers, three-pagers, five-pagers, ten-pagers. It was a matter of organizing the clusters, because I had an intuitive sense of the basic theme.

The storyline hit me real strong in 2007. Then I built the pieces and parts and chunks along that. That was surprising because book three... I started book two immediately, I didn't even stop. I went from one on the drawing table to two. I flowed right through. I had difficulty in the illness in my family between books two and three, so I had... a not-complete devotion of attention to three immediately. It was still there. The drawing table was always waiting and I knew the story. I had some devices. I had part of the wall that I gridded out; I used post-it notes to help me manage the pages. Even though in book one I forgot to number the pages. [laughter] But I knew what every page that I scanned was called -- page 36 or something like that. I had a way of organizing all of the pages. I did do them according to, "Okay, I have to work on 37. What does 37 need?" And I kept on the grid a sickbay list -- page 36 needs corrections! Page 53 is awkward; there's no flow to page 54.

It was a lot to juggle.

SPURGEON: Were you getting feedback from people as you were doing it?

SPURGEON: Were you getting feedback from people as you were doing it?

TYLER: No. And it's funny, because everyone knows I'm married to Justin. We do not have a buddy system for feedback for the work. So I would have to mull it over. I would go out and do some yard work, come in and just live with it. Crazily walking around the house, talking out dialogue to myself. "'That son of a bitch!' Well, no, he wouldn't say that. He would say, 'That cocksucker!' Yeah! That's what dad would say! [Spurgeon laughs] Not 'That son of a bitch!'"

So I was on my own in my own world, my own thoughts. I'd walk the dog and I'd be, "No, that's not how it goes; it goes like this." It was constantly here, constantly in my consciousness, feeling around for it, feeling around for that right vibe. Towards the end, with my parents and the illness and stuff. In the Olympics, I love this thought, Oksana Baiul was down, didn't know she was going to win the gold, so at the end of her program she throws in a quadruple toe lutz and another triple toe loop! [laughs] There were a couple of pages I did throw in off of my grid, off of the narrative. Things that had to be in there. I needed them because of what happened with my parents. I added about 20 pages to book three.

SPURGEON: Are you willing to identify some of the pages?

SPURGEON: Are you willing to identify some of the pages?

TYLER: Yeah. My mom at the beginning. I'm looking for her in the landscape. I'm reintroducing the characters. I had her years ago draw that drawing -- I said, "Mom, make a picture for the book." She kept saying, "I don't know why you have to reveal about us in public." She had the drawing, and I knew I wanted her to say that. I had to draw her leaving the panel, but she had passed away already. So where I have the lady manatee, the metaphor that came up for her, originally I was just going to talk about mothers and daughters, but I have her exit that scene on her wheelie cart. She says, "You should ever know that I love you." That's one of the things she told me before she died. "Ever know." She was riffing off of the book title. I had her in her little scooter leaving that sequence. That's not what I had planned originally.

There's another part where... my dad was not a good guy. I don't want to say that. [pause] He took her illness very hard and awkwardly. He got crankier and more off-putting. I put in that section where we go to the motel because the asbestos is all over the house. That's all true. [laughs] We go to the motel. I added the part where I had to go back and get her meds because she couldn't breathe. He's asking for his pipe. That was the way he was. She was over there in her hospice bed just wheezing away and he was trying to light up his pipe. I said, "Dad, you can't do that in here." "Hell, a man should be able..." I said, "Mom is struggling; can't you see?" So I give a touché on that.

I think the crabbiness at the end... I had him crabby, but I really pointed with those sawblades, I went to the level of his crankiness. I was so upset with his behavior. I kind of turned the dial on that one.

SPURGEON: One of the distinguishing characteristics of this work overall is the sheer number of unique narrative solutions. In this volume alone you have a text-heavy section, and these panoramic scenes, and you have the grid as well and you have these pages with a lot of white space where you drop details. It's an almost dizzying array of choices.

TYLER: Did it feel like too much to you?

SPURGEON: No. No, no. I thought that element was wonderful. There's no criticism implied in my pointing this out. My question, though, is at what point while structuring a work like this one do you land on the way you're going to approach it on the page? The fact that you're doing chunks here and chunks there suggests that maybe you're finding your way through how you're going to tell it. Maybe that's why there are so many different approaches?

TYLER: I did know that it could be jumbled, very jumbled, if I didn't have some order. Order in the court. That's why I do have the grid structure. Six panels on a page. I tried to keep some saneness that reappears except for these episodes. When we go to St. Louis, it's pages from the journal over, basically, strips of paper that I'd taken white paint to to make them try and look like roads. Paper that I tore, and like a collage, stuck it on there. I feel like... that saying in architecture? form follows function? -- there were times that I felt like I had to get the mood. There's conveying the content, the information -- communicating that. And then there's the artistic part of communication. There were times when I just had to get it across in a better way.

My mom used to say in an argument, "I'm not going to draw you a picture!" or something like that. Well, I do. That's my business. I have to convey a mood as well give you some information. So there are the words, there's the pictures, and there's the intangible element within that. That's the play part. That's what I like.

Fantagraphics gives me full range to do whatever I want. They may say, "There needs to be a hyphen or a comma" or something like that. Or this word is spelled wrong. Although very little. I pride myself on my great spelling. I don't get called out on that too much. I try to improve my word skills, try to write better because I feel like writing is my weak point. But then I'm so afraid to draw. I'm really not much of a cartoonist, I guess. [laughs] There are people that can just have at it, but it's very hard for me to draw. And writing, I was a troubled reader growing up. So I work on these things, try to improve constantly. I forgot the question! Where was I going with this?

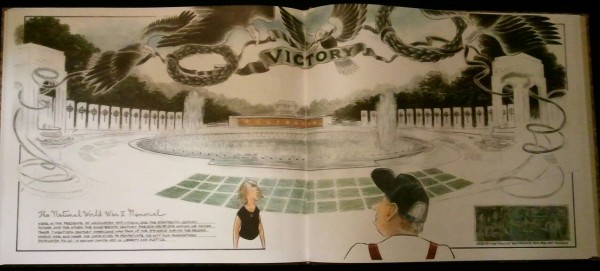

SPURGEON: Let me make it more specific. There's this climactic section where you and your father visit the National World War II Memorial.

SPURGEON: Let me make it more specific. There's this climactic section where you and your father visit the National World War II Memorial.

TYLER: Yes.

SPURGEON: The work opens up there, and you tell that part of your story in spreads. You get a sense of the scope of the place. You also use a muted color scheme, less lively than some of the earlier scenes. I was wondering how you made those choices. Maybe that will help focus my impossibly broad question! Why did you go with these vistas? I think that's really effective.

TYLER: When we went there, oh my God, it was so grand and spectacular, the space itself. When you walk into the memorial, you literally kind of walk down into it, and it opens up in its grandeur. It's wide. There's the Atlantic side over here, the Pacific side over there. It has this wide-open feeling.

I kept... here comes "intuitive" again. As I was drawing, I kept having this feeling of a circular motion, swirling air and big sky. It was all there. When I started to draw those pages, I was literally drawing gigantic ovals on the paper. I was looking for it, because I don't trace. I do reference a photo, but at some point I let it go and try to get the feel, get the vibe. I have everything up to it in the world of the comic panel -- panel to panel sequence. And then we're in the hotel room there are close-ups on my anxiety over not being able to sleep. All of that. And then, yes, as we go, get closer to it, I wanted to get the reader to the point how we fell when we were in there. Good God. It was magnificent and open and spectacular. I felt the way to do that was to open the space up. I don't know if you've ever been there, but the sky does not have birds in it with wreaths. That is confined to the towers that say Atlantic and Pacific. In order to reinforce that feeling, I didn't want to show that and then walk over there and look up and show that, I kind of combined sensations of being there and walking around that.

If you turn the page it had the columns. He wanted a picture with every state he lived in over the years. I had to make the columns as a separate thing. I wanted the gravelly effect. It's a technical thing. I made this big circular thing. I needed to have the reader look at the thing and then almost like a spiral come out, look at the four things, and then spin over to dad walking over to his side, the Atlantic. It's another circular motif. Then you turn the page again. It was, again, inspired by the space itself being near the water. They have these water features there.

He literally did have a meltdown. He's a little, bitty guy. He's shrunk with age, and he's frail. Within this gigantic space I needed to show him coming apart. What tipped him off was the sound of the water, and the names they have carved in stone of the places. His story was that he didn't know where he was, and all this kind of stuff. There would be "

Ardennes" and all of these names, and he didn't know. It made him feel that confusion again. And that water, and the bigness of it. He got lost in that moment. He fell apart.

I knew that the minute I started the comic. "Comic." [laughs] I doesn't seem like the right word. I knew the minute I started the work, I knew I had to bring the reader to the moment when we were at the memorial and he fell apart. When I first started the work --

Kim [Thompson]'s going to hate me for this -- but I did show it to some people at bigger, New York publisher companies. They said, "We don't think your dad is very interesting." One place said that. I didn't have it in the shape I have it now, I just said, "I want to tell a story about my dad. He was brave and he had cancer and he was in the war." "We don't think your dad is very interesting," was one of the answers. I remember thinking, "They don't know him." Then I thought that's my job as a cartoonist: I need to get people with me in that moment. I need to bring people there. I have to describe and define him. That set up the book.

I took it to another place a couple of years later and they said it was great, but it was too random. I didn't have my real story. They were the ones that said, "We can't work with people who are intuitive. You have to have your script written out." And I said, "I don't work like that! Sorry!" And I thought, "The hell with it. Who do I think I am? I am a weirdo artist from

Weirdo magazine. I need to approach it like that, the way that I know best. That's what works." I said, "Goodbye, New York." I can't work with an editor on this big thing. Leave me alone. That was 2007.

I had high hopes. I think it was because of... [sigh] the money, the time, the commitment! I did this on a shoestring. I did this along with... I'm going to say it. Food stamps. I did it with practically no resources. I work as an adjunct. I teach a class. That's what keeps me together. I'm poor folks, baby.

SPURGEON: I wanted to ask about another page, a little bit later than that, the conversation with you and your father in the truck after the memorial. It's almost very plain in a way. I liked the cats and dogs and the buckets, the cartoon jokes, but it's a very unadorned page. If you were flipping through the book, you would not think that this is an important scene. I wanted to know why you did this one in such a straight-forward way. Because the content... I actually gasped, took in air at one moment reading it. It was affecting. But the presentation is... was that on purpose?

TYLER: Oh, yeah. We had gone through the moments of his remembering picking up the dead and being called out as a wuss, which is why he volunteered for that job. And not remembering... the whole confusion element, his being so alone with all of that. There was this grandeur and spectacular element to the memorial, but for the most part, what we know for sure is that soldiers pretty much don't have that experience. It's little things that tip them over. Stuff they can't forget. The accumulation. What

Ernie Pyle described as layer upon layer of awfulness encountered. War isn't about

Audie Murphys. It's about regular guys like my dad, and the damage. We got to the truck, and this is the truth. It was pouring when we left the thing. Epic rainstorm. It was true, I said these are soldier's tears, stories never told. How many... I just felt how many people carried around stories. I get in the truck and I'm with one of those guys. Whose story I know. It was a flash flood; it was awful. He didn't drive because his truck wasn't available.

We pulled over. He said, "They say love is the answer." He started talking about Anne, my sister. It was shocking, because I thought we had had our moment. It was really sweet... in the little cab of the truck there, it was private and personal, like a whisper. Real plain. That's why I did that. I just wanted that to feel that way. This little... private reveal of that, how war sent him to the gates of hell but Anne pushed him in. I wanted to have that be the focus, not any of the environment. The environment is that we were in the truck, the outside world, everything had pushed us into this little spot. It was not like... it wasn't like, "I was happy and he was happy because we resolved something." It was a very quiet realization. That's what I had. I had to get the reader to that place at the memorial, and I also knew that there was something about our time in the truck -- I couldn't have them compete, but it had to be a great other side of that moment. I just kept us in the cab of the truck. Eventually we got home.

SPURGEON: You disparaged your skill as a writer, earlier, and it made me think of a panel -- not a dramatic one, almost a throwaway one -- from the wedding sequence. Right near the end. That whole scene is snappily presented and the writing seems to me to the point, and would seem to speak against your self-portrayal of a quarter-hour ago. At one point you write, "A wedding is a mash-up between loved ones and strangers who politely spend the hours attempting to sort out complex, familial alignments while slowly getting plastered." [Tyler laughs] That's a great line. How much do you worry over your writing. Do you go after every word, do you pick apart the text when you're creating your comics?

TYLER: I do write over and over trying to find the right... "mash-up." [laughs]

I've always been self-conscious about writing because I was in the bluebirds reading group. You know what that means. Sister put me in with the slow readers, the bad readers. Something like that. I was four years old when I started school, because my birthday was in November. Nowadays they would have kept me until the next year. What I learned from teaching first grade and second grade is the child's brain is ready for language, there's a window that opens up at a certain point, and you're ready to read. I was a working class girl, my mom did not read books to us at night. We had to get to bed, so that we could get up in the morning. So pleasure reading was not something that was around. I did not have any prep.

Then when I was in kindergarten I was too short, too small, and the kids would laugh at me because I would stumble on my words. I didn't know what this stuff was. I got put in the challenged group for reading. I had to play catch up throughout school. I think that's why I developed this kind of thing. I had to read the world based on visual clues and sound.

I did learn one thing about myself throughout this book: sound is everything to me. When I hear somebody say something to me, I remember how it sounds as much as what they said. More. It's the sound that becomes the shaper of the form. I know with the wedding I have to go [Tyler sings a series of musical "doots"]. You know? [Spurgeon laughs] Then I figure out the words on that. I walk and talk around the house. I'll go for a walk. I'll get in the shower. I'll order and frame up the words, in the shower, talking through the words. It's something I need to nail down. You gotta have in comics, I feel, you have to build a great house. That's the architecture. That's the panels and the order of the writing, all that stuff. Then the plumbing, that's the words and the composition of the art. I said it was troublesome to draw. I get the panels drawn, the words written. I often have to go back and re-do it because it has to ring true. Then I start to work on the drawing. That's when I get to nail-biting. I have no confidence in my ability to draw. Every panel I draw I have to struggle with, "Can I do this? Uh-oh. I don't know if I can draw. I don't know if I can do that." Then when it's done it's like, "Oh my God." So I try another one. Every single panel I have to get all my confidence together and move forward. It's not easy. When you go to book signings and people pull out their sketchbooks and say, "Can you draw me a picture?" I can't! I have pencil it and work it over a couple of times... I have no confidence. It's a struggle for me.

I'm glad you brought that up about the words. I'm very concerned with the writing and the language and how it reads. I do obsess more over that. I'm equally obsessed about how the picture looks within the panel and how the panel works within the page, so that the whole thing has a sense of being something that works, that leads to the next page and come from the page before.

SPURGEON: You mentioned in an interview once that you would talk to people to get dialogue closer to what they might actually say. Do you do that with the visuals, too? Do you tweak, or check with people, about the visual aspects of your comics?

SPURGEON: You mentioned in an interview once that you would talk to people to get dialogue closer to what they might actually say. Do you do that with the visuals, too? Do you tweak, or check with people, about the visual aspects of your comics?

TYLER: You have to make sure you got the right lamp in the room. Otherwise it's somewhere else. What somebody is wearing. Mom's wardrobe, her

JCPenney's wardrobe is throughout the book. Dad, he was pretty simple because he always wear the same clothes: the blotchy, stained pants. The suspenders.

Through the book I wanted to make sure I captured my own transformation. When Justin leaves at the beginning I'm wearing a

49ers jersey. Could you get any more unsexy or girly attractive than that? Right? At the time, when he left, the 49ers were the team in northern California. I didn't have a jersey but I had... Julie had one or something. That was the mode o' day. I was right in the middle of the raising the kid thing. Women do not feel sexy and all that stuff... you just can't. You have the kid, you have the homework packet. So many things. Another thing: I have to look like a sex object all the time! That takes a low priority. You want to look nice. And aging is starting a hit. So in that panel, I wanted to draw a 49ers jersey because that was as far away from romantic awesomeness as I could get. As I transform through the book, I transform my look. I get back into my being. Everything from my hair to the way I travel around in the panels. It's clothing. It's telephones! At first I'm on a land line. At the end I've got a cordless. There's a cell phone. Cars. Everything. All of these details. I knew I had to show across the time... a phone can really anchor an ear. A well-placed black telephone. We still have a black telephone with a coil. We still use it.

SPURGEON: We talked in 2009 when the first book came out. You expressed some anticipation that the book might garner reactions from other children of veterans. Your generation, and feeling the burnt of this undiagnosed trauma they went through. I wonder how that developed. Did you hear from other people? Do you think your work has been reflected in work that others are doing? Or has that not developed the way you wanted it to?

TYLER: I'm kind of disappointed that it hasn't had that audience. I know that is a great audience. I'll tell you why. This last Fall I was at

the Military Writers Society Of America -- there's actually a group like that. I was asked to do a presentation. Twenty very devoted people came. They were blown away by my presentation. Not only because these are people that write, and I showed them: "And now you gotta draw it." I have a powerpoint about what the studio looks like, and the effort. They were amazed by that. There were also people there who had written on the topic. There's a woman,

Leila Levinson, she had written about the very same topic. We didn't meet until that conference. We became fast friends. She believes the same thing, that this is the big shaper of our generation. And we have it in our minds to put together a conference. We wish we could roll it back 20 years because the baby boomers are retiring and moving to Costa Rica. What do they care about issues? When people of my generation, and they find it and they read it, it really resonates with them.

I'm sorry about the way the bookstores... you go to the graphic novel sections and there's

Hellboy! [Spurgeon laughs] There's Chris Ware's

beautiful, giant thing. There are all these other great titles. But someone that is interested in history or World War 2, or the things that this would strike with them, they're not going to go to that section. I've said that before at the library. I've asked, "Why you can't put it with the military writers?" Put it next to Leila's book,

Gated Grief -- it's about post-traumatic stress. Put it out there for the veterans to find. Amazon, come on! Categorize it. It's under graphic novels, and then women's graphic novels. Those are the categories. If you like Fantagraphics and you want women cartoonists, you're going to find my book. But if you're a military person, you're not going to get to the book. Why are there these screwed-up categories?

SPURGEON: I think that's coming. Slowly.

TYLER: We were saying that 20 years ago.

SPURGEON: When I told a bunch of people I was going to interview you, announced it on Facebook or via Twitter or something, I heard back from about a half-dozen folks -- about par for the course -- but this time they were all fellow women cartoonists. I remember when you went to San Diego a couple of years ago a lot of the female cartoonists I knew there attended your panel. Do you feel a connection to the younger women cartoonists working right now?

SPURGEON: When I told a bunch of people I was going to interview you, announced it on Facebook or via Twitter or something, I heard back from about a half-dozen folks -- about par for the course -- but this time they were all fellow women cartoonists. I remember when you went to San Diego a couple of years ago a lot of the female cartoonists I knew there attended your panel. Do you feel a connection to the younger women cartoonists working right now?

TYLER: Wait a minute. Did you say you heard back from younger women cartoonists about my work?

SPURGEON: It was actually all women cartoonists. That's what I'm saying. Usually I hear back from a range of people. This time it was only women cartoonists that wrote me. I wondered if you felt a connection, because it seems like they may feel a connection to you. I think your work is admired, generally.

TYLER: I find that funny. Not funny ha-ha. I find that interesting because as a cartoonist -- and you know this is true -- you work in your bubble, your isolation unit, and I don't get to go to these conferences. I went to San Diego by the grace of being asked to come. I don't have the resources to travel around and promote my book. I'd love to do that. I haven't had time, and then last year with my family in such a difficult state I didn't have time to go to any of these things. I probably should go and meet people. Get out more. I've got a lot of

Facebook friends and I know people through Facebook and maybe having met them at a couple of conferences. I feel so inadequate because I can't meet the need. If someone comes out with a great book and I see it and I love it, I don't know what to do about that other than say, "Oh, your work is great. I really like it." It sounds so fake.

I try to be supportive. I try to

like. I hit the "like" button on as many people as possible. But I don't have fast friendships with the women that are working, probably just because of the physical... I remember hanging out with

Aline [Crumb], for example. And

Diane [Noomin].

Phoebe [Gloeckner]. We physically hung out together. We'd go to

Ron Turner's burrito party. There'd be some function at Aline and

Robert's. I don't know how close you can be as a friend just by hitting a like button. I'm kind of embarrassed and sad about that. We don't get to show up physically for each other. I can't show up physically. I'm honored and pleased to know that women showed up in terms of this interview. I feel honored.

SPURGEON: You're always honest about the costs of being a cartoonist. Do you worry after younger people that want to make comics or that wanted to try something like you just completed? Is the cost of doing this kind of work something you worry about for others?

TYLER: Do you think people would be surprised to know that I did food stamps to get the book done?

SPURGEON: I don't think surprised as maybe gratified that you would talk about it so openly.

TYLER: About poverty?

SPURGEON: About how tough it can be to make art, or orient yourself towards making art, unless you're very lucky. A lot of the very youngest artists have come up in this age where there really were some book contracts out there at one point [Tyler laughs], and it seemed like that was a thing that might continue. Some of the cartoonists I've talked to this year, those under 35, a lot of them are readjusting their expectations.

TYLER: Because of the economy.

SPURGEON: That, and because suddenly fewer people want a book from them -- maybe not a second book, maybe not a first.

TYLER: How do you get one of those? That would be fun. [laughter]

Fantagraphics and I have a hippie handshake deal. Which is fine because we're from a different generation. I trust Kim and

Eric [Reynolds] and

Gary [Groth]. They've done okay by me. It's not been New York prices, but it's been what they can do. I'm okay. I'm not in foreclosure.

All right... here's the deal. I'm an art nun. [laughter] You take a vow of poverty when you enter this business. It's not about the lifestyle, it's about how can I get this work done. So the first thing I learned as an artist when I went off to art school back in the '70s was you get a job that won't drain you emotionally and will allow you to have the time to do your work. I've been working under that same paradigm. And if you work hard, you'll get a bigger gig. You have to stay the course. I have had times in my life where I've taken -- this is the absolute, god-awful truth -- go through the pantry, take a couple of cans and return them so I can buy a tube of red, a tube of yellow and a tube of blue. Maybe a tube of white. Get some cardboard, and do a little bit of art. I still have returns I do because I need a bottle of yellow ink. At the same time, I can't put forward poverty as my opening shot. People can't see my hobbling reality. They need to see the triumphant result. My art will outlive me. Not my poverty. That's not going to matter. What matters is on the page.

I gave up a long time ago on a fancy wardrobe. I'm a thrift store girl. I gave up a long time ago on vacations. When I'm asked to come to San Diego, I make sure I do a little sight-seeing and have a little fun when I'm there because that's my vacation. I can't afford to go the Cayman Islands. I just came back from Europe. Someone graciously, the

Amadora Festival... Portugal... that was wonderful. Otherwise I would not have been able to go to Europe.

I could not have done this book as a young person. Not just because of the obvious chronology, but because I wasn't ready. I didn't have the emotional connection with some of these broader themes. When you're young you want to draw about young people things: the rent, the landlord, the boyfriend. Which is what I did when I first started out. Cursing them out in print.

I don't know if it's right to air my reality here. "Whoo! This girl's poor!" [laughter] For the younger people, if they're going into it thinking they're going to have contracts, or a certain lifestyle? No, no, no, no, no. You go into this to say something. To communicate.

*****

*

Carol Tyler

*

Carol Tyler at Fantagraphics

*

You'll Never Know Book One: A Good And Decent Man

*

You'll Never Know Book Two: Collateral Damage

*

You'll Never Know Book Three: Soldier's Heart

*****

* cover to the latest book

* self-portrait by the cartoonist, the one used for the Chicago conference earlier this year

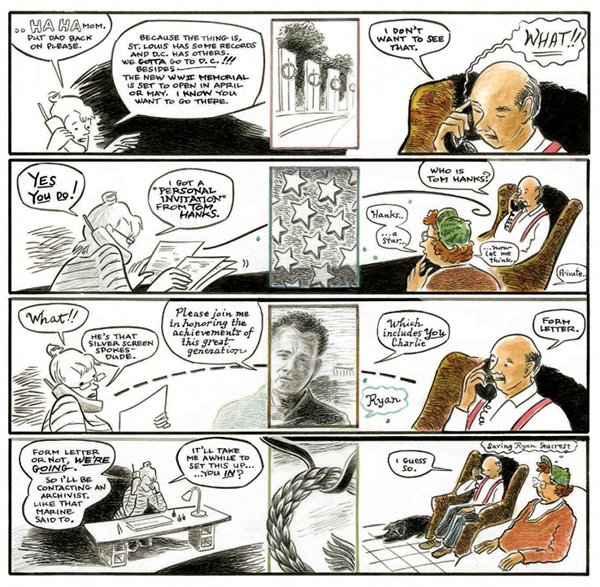

* one of the dizzying variety of narrative solutions employed in the book

* an added scene

* the big memorial spread, photographed because I couldn't manage to scan it even though I thought I could

* Carol's dad getting his picture taken in front of those various state columns

* one of the lovely dropped-border panels that Tyler occasionally uses

* the sturdy grid

* compelling, dream-like image from early in the third volume (below)

*****

*****

*****

posted 4:00 am PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives