December 18, 2012

CR Holiday Interview #1—Alison Bechdel

CR Holiday Interview #1—Alison Bechdel

*****

Alison Bechdel

Alison Bechdel released her second acclaimed memoir this year,

Are You My Mother?, a delicate, layered portrayal of mother-daughter dynamics, the voids created when two people don't always connect and the pervasive influence of art as a way to deal with as much of the resulting hurt as humanly possible. It can be read both as a bookend work to Bechdel's phenomenally successful

Fun Home and as a stand-alone volume. Bechdel's book is as narratively complex as any comic I've read in a long time, triply so for the fact that Bechdel has a tremendously wide-ranging audience, many of whom are not fully soaked in various comics formalities. I saw

the Guggenheim Fellow this summer at

Comic-Con International; she was the first cartoonist I asked to participate in this year's holiday series. I'm grateful that she agreed. We spoke just a few days ago. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: These book roll-outs seem endless now. Do you feel like you've been putting Are You My Mother?

out there for months and months at this point?

ALISON BECHDEL: Yes. My year was kind of turned over to it, in a way.

SPURGEON: Do you know why that is that the promotional periods are extended now? Is it that there are so many different opportunities to do media now? Is it that everyone wants to see you? Are there more events?

BECHDEL: I guess it's so important to promote a book that you need to do as much as you can. Everybody's competing with so many things, entertainment-wise. [laughs] I think of people like

Virginia Woolf, you know, that she would ever go on an author tour. [Spurgeon laughs] People just didn't used to do this. It's not just comics. It's the whole publishing landscape. People just have to flog their stuff intensely.

When I was doing

my comic strip, I would work for two years compiling enough episodes to put together a collection, and then I would go out for a month, a brief publicity tour. I got used to that rhythm, and it sort of made sense. Like okay, yeah, I can go out and articulate a little more carefully what it is I'm doing, connect with people personally. That made sense to do. It's just on a different scale now that my work is being read by a bigger audience. It's a trade-off I'm happy to make. [laughs] I'd much rather be selling stuff than not selling stuff. But it is quite draining. And it's keeping me from work. I haven't been able to start a new project all year.

SPURGEON: Are you strong-willed about curating this period?

BECHDEL: I'm starting to get a little more discriminating, but until recently I just have done whatever anyone wanted me to do. That's how it goes. You have to do that to a certain point. But then the things that people want you to do get out of control and unreasonable and you have to start to say no.

SPURGEON: Is there an unreasonable request you can share?

BECHDEL: None of them are unreasonable on their own... it's the collective force of them. I often get asked to come to comics events in Europe. That's really amazing, but I don't have time to do that. You know? They're paying my way, but I would lose a week of work. [laughs] This is the most annoying thing; nobody wants to hear about how you're getting invited to Europe too often! [laughter] I just find it really stressful. I hate to disappoint people. It's great that they want me to come. I don't know how to say yes to everyone. It's impossible.

SPURGEON: That makes me wonder: what is your penetration into non-English language markets? I'm not sure I know how your work has been published overseas.

SPURGEON: That makes me wonder: what is your penetration into non-English language markets? I'm not sure I know how your work has been published overseas.

BECHDEL: Well... a lot. It started with

Dykes To Watch Out For, just a few languages: German, French. But

Fun Home was pretty widely translated, I lost track of the numbers. But pretty crazy stuff like China, Korea.

SPURGEON: Do you hear back from readers in those markets? Are the reactions different? I'm kind of at a loss to think right off the top of my head how different cultures might process your work, or if there would be a discernible difference. Your work is very observationally specific.

BECHDEL: I'll get letters from readers in Brazil and Sweden, all these places, and they say the same thing I hear from US readers: that it moved them, or they connected with something, somehow.

SPURGEON: Are You My Mother?

is constructed in a really, really complex fashion. When I started to think about what interested me about your book, that's what I kept coming back to. I don't know how on earth, just in practical terms, you put this together. Even in the first section, there are five major beginnings any one of which could probably carry an entire book. And you have multiple threads throughout the work, and this kind of ease in moving back and forth between them that's wholly impressive to watch. How did you keep track of all the different through-lines that you employed?

BECHDEL: [laughs] It's a really crazy book. I'll go in there looking for a certain page, for some reason or another, and I can't even find it. There's no chronological order to it. What is the principle? The principle is... [laughs] I can't tell you, Tom. It's been sort of interesting over the course of this year talking about the work with different people with different contexts. At first I thought, "I didn't pull everything together here; this book doesn't make any sense." [laughs] But I'm starting to feel more okay about that. Maybe it is a more experimental, enormously complex book that's not going to have a straight-forward through-line or narrative. And I think that's okay.

SPURGEON: I think it's a strength of the book, but it is this assault of different time periods, different thematic points and developments. I was never lost

, but it seems to me the making of it must have been insanely difficult.

BECHDEL: It was insanely difficult. It was really... nauseating at times, steeping myself so deeply and protractedly in the inner workings of my life. Reading old diary entries for hours and hours and hours, trying to correspond different events in my life based on these archives I had, like my diary or my mother's letters or my father's letters. I had all of this material from different points in time.

I realized when I was working that this is what our unconscious is like. There's no chronology in our unconscious. Everything is jumbled in there simultaneously. Every moment that we're living and having experiences, we're bringing to bear all of the other experiences that we've had. This is what is exciting to me about graphic narrative, that you're able to do a layered complexity that I couldn't imagine doing with just writing. Great writers can do it with text alone, but I couldn't. I feel that because I'm able to use visual storytelling, I can push how complex the ideas are that I'm trying to talk about.

SPURGEON: There are visual signifiers that lets us know where you are; we can figure out by the look of different things, and even the formal arrangements. Were you just kind of feeling your way through it, then, or was there a right-brain puzzle aspect to this?

SPURGEON: There are visual signifiers that lets us know where you are; we can figure out by the look of different things, and even the formal arrangements. Were you just kind of feeling your way through it, then, or was there a right-brain puzzle aspect to this?

BECHDEL: It was very much a right-brain puzzle. If it had just been me writing down this as stream of consciousness, it would have taken a year instead of seven years. A lot of it was going back and reworking stuff, trying to find the narrative threads that I believed were there. That's what I love about writing memoir, dealing with actual lives and things that really happened as opposed to making stuff up. You have this constraint you're always pushing up against: what really happened. You can't add stuff to make a nicer story. I was working hard to find a narrative that I believed was there. I'm not sure I actually succeeded [laughs] but that's what drove me.

SPURGEON: When you talk about constraints, it reminds me of your strip cartoonist background, in that a strip cartoonist is heavily defined by the formal constraints of that avenue for publishing. I think that makes transitioning into longer works tougher for some strip cartoonists because there's something terrifying about a blank page that can in effect be anything.

BECHDEL: Oh, my God. I totally had that problem when I started

Fun Home after having done a strip for 20 years. I loved the constraints. It was only when I learned that there are new, different kinds of constraints [laughter] with a longer form that I was able to really grapple with it. Chapters. Things having to show up on a left-hand page. Page layout. There are all these other things you have to start attending to, which I didn't have to when I was just trying to fill those little boxes.

SPURGEON: If you think about it in those terms, this work is kind of loaded with such constraints. You have rigid chapters, a recurring dream motif, and there are elements of formal play on the page that repeat... it seems like you were kind of finding your way through all of this in terms of comics structures, or that they were at least a help to you.

SPURGEON: If you think about it in those terms, this work is kind of loaded with such constraints. You have rigid chapters, a recurring dream motif, and there are elements of formal play on the page that repeat... it seems like you were kind of finding your way through all of this in terms of comics structures, or that they were at least a help to you.

BECHDEL: Yeah. There's very much an architecture. It's not capricious at all.

SPURGEON: Do you feel like now you want to break out of that? In fact, with the book itself, did you worry about it not being spontaneous?

BECHDEL: Very much, especially because I wasn't actually drawing it for such a long time. I felt my drawing ability atrophying. I'd do a few sketches here and there, but for a couple of years I didn't even do any drawing on this. I know that's terrible, and that I shouldn't admit that. It felt a little overly-cerebral and I very much want to do something where there's more physical drawing from the beginning. I hope that my next project will be like that.

SPURGEON: You thanked your editor at the end of this book. Was that the stage at which your work with the editor becomes the most important, that writing part of it?

BECHDEL: Yeah. I have

this great editor that I worked with on

Fun Home and on this book. So we've gotten into a routine about it. She's able to read my layouts, with descriptions of what the panels are going to show, but they don't necessarily have any sketches there. She can edit based on that.

SPURGEON: You've mentioned Fun Home

a couple of times, and I have to imagine that lends a completely different level of complexity to this project, knowing that it will be released in Fun Home

's shadow -- or that it will at least come out after such a well-received work. Fun Home

is also a work that's still fresh in people's memories; I think it's stayed pretty front and center in terms of works released in the last half-decade. Was there fear in doing something like Are You My Mother?

as a follow-up?

BECHDEL: There was

intense fear. It was difficult working in the shadow of that book, which was so strangely successful. I wasn't expecting that. I spent a lot of time in my life adjusting to being a successful cartoonist who was considered part of the mainstream after a career in the shadows. That was kind of traumatic. I didn't want to repeat

Fun Home. I felt like I had to push myself, to do something different and more complex. Actually, I don't know if I was conscious of doing something more complex. I wanted to do something different. I was very anxious...

I'm sorry, Tom, I'm sort of blithering.

SPURGEON: No, this is great!

BECHDEL: Even though I was working with this knowledge that I'm in the shadow of this work that people like, it was mostly the weight of expectation that was daunting. When I was working on

Fun Home, no one knew I was doing it. There was no pressure, zero pressure. With this book, I knew that people were waiting for it. I had already sold it. [laughs] So there's financial pressure. But knowing that there was an audience waiting for this book was very inhibiting.

SPURGEON: You were pretty honest in the book about certain financial pressures you've felt at different times. Did that shape the book at all, did you feel like you had to do a memoir because that's what's expected of you, or that you had to do one now to take advantage of the timing? Did the commercial interests intrude into the creative in any small way?

BECHDEL: Gosh, that's a good question. In terms of the genre, I don't think it changed anything. I wanted to continue working in memoir. Autobiographical stuff. [pause] The thing is, I sold this project very early. I hardly had anything; I basically wrote a proposal for it. It changed a lot after that point. I didn't really feel a lot of financial pressure to make it into something because I had already sold it. [laughs] No one was going to be "You should steer away from this; this isn't going to sell." They seemed happy to publish whatever I did. That being said, there was a kind of wish I had taken a little more time conceptualizing the book. I did it in a big rush because I did need the money. And maybe part of what was difficult about the project was getting out from under this proposal I had written, which was very different than what I ended up doing.

SPURGEON: How different?

BECHDEL: I don't know. Not

that different. The proposal -- god, that's so boring I don't want to talk about it anymore. [laughter] It really wasn't that different.

SPURGEON: The other complexity question I had is that given the book has this multi-layered construction, and given you know that you have a number of readers that probably aren't reading a lot of comics, is there a desire when you're executing it on the page to keep it more rock-solid? It seems like you allow the pages to be very straight-forward, and have some very conventional storytelling beats, even as the story itself grows more complex. You use a lot of words, for example, both as a visual tool and to get at key points of the narrative. Are those things that you depend on in terms of making things clear? How concerned were you generally with clarity?

BECHDEL: That's part of it. I like a clear grid. I admire people who do incredible page layouts, but the other part of it is that I'm not that good at design. [laughs] It's easier for me to stick with the standard page layouts. I did a little pushing out of the boundaries with this book. With

Fun Home, there was only one page spread that had a bleed, otherwise it was just standard grids. In this book I did a little more with bleeds and with black areas.

SPURGEON: A couple of the specific solutions you used intrigued me. The highlighting of text?

SPURGEON: A couple of the specific solutions you used intrigued me. The highlighting of text?

BECHDEL: Yeah!

SPURGEON: How did you stumble across that and what did that do for you?

BECHDEL: I went through a number of different techniques with that. I knew from the outset I wanted to include quotations from books like I had in

Fun Home, but also the quotes in context. I love books, and typesetting. I thought it important that if I was conveying these people's ideas through quotation I should show it in the actual font and leading: the page I read it on. Then I had to find a way to highlight specific passages I was quoting. At first I did that [laughs] -- all these complicated things. I used a gray wash over the text. Then the red color highlighting the passage I wanted to read. But they were kind of illegible. Then it was highlighting the passage in the red color and then erasing the highlights, the parts I wanted people to read. I thought it worked pretty well.

SPURGEON: I thought it was effective, and it's not something I've seen people do.

BECHDEL: I felt a little weird about it, because I was doing the deleting of color with a graphic tablet. I use a graphic table for corrections and things, but I don't really draw with it. In this case I felt I was making a lot of lines with the graphic tablet, which was new. It's not a part of my process.

SPURGEON: There are a few flourishes, some very definite employments of a visual motif. There's a page where you're talking to one of your doctors and above it you're describing your theological foundation --

SPURGEON: There are a few flourishes, some very definite employments of a visual motif. There's a page where you're talking to one of your doctors and above it you're describing your theological foundation --

BECHDEL: Oh yeah.

SPURGEON: -- and you use three visualizations of what you're saying. And it's very funny, these visual representations: God, the universe and God in the universe. I like the playfulness of it. I also wonder that given how much dialogue there is in the work, how much hinges on conversation, if you were extra careful to make sure there was some visual interest on the page. I wonder if that was an example of that impulse, perhaps.

BECHDEL: [laughs] That particular passage is so effective and so good I can't help but think I ripped it off from somebody. [Spurgeon laughs] I kept wondering where I had seen it. No one has accused me of this yet, so maybe it's my own idea. When I was writing that scene and that particular therapy passage, I had all of these notes from my time in therapy during my 20s, [when] this really powerful stuff happened. I was trying to map this out into panels. I realized very early on it was deadly. Nothing's really happening. It's the same people on the same chairs. The real action, even if it's in what we're saying to one another, you can't really see it. It's difficult to tell a visual story about something that's completely not visual. I kept compressing things down until this one scene was a one-page spread, even though the sessions went over the course of a year. The whole cosmology discussion became three panels.

SPURGEON: You employ a few silhouettes and some black backgrounds in dramatic moments; is that an important desire of yours, to use the blacks to stop the eye or to isolate an image on the page? Like when the mirror falls on you, the eye just stops on the strong black-and-white panel you did. Were you conscious of the power of the blacks you use that way?

BECHDEL: Uh... yes. [laughter] There were certain emotional beats in the text that I really wanted to make sure people felt. I was trying to do something visually arresting on that page. There's one page of the book where there's no line, it's all done in color. There's no line art. That was an important moment. On another I'm doing this Winnie The Pooh analysis; that page bleeds red. It's a way of accentuating a particular idea or emotional point.

SPURGEON: Are you conscious of how the eye moves, and manipulating that sense of time?

BECHDEL: I'm just trying to get people to read stuff in the order I want them to experience it. I'm not always as effective at that as I'd like to be. I'm not thinking compositionally like Jaime Hernandez in terms of where my blacks take the eye on the page. I don't have that kind of graphic skill. Or with the whites, for that matter. He's a master of whites.

SPURGEON: I do think your use of blacks has a significant impact. The conclusion, for example, there's a black backdrop, followed by dropping the borders altogether followed by an isolated panel. It's very attractive, but it also lends weight to the moment, and frames what we're seeing. Did you struggle with the ending given how much you have going on in the book? Or did the ending come to you earlier, making the struggle more in how to get there?

BECHDEL: The ending came to me... I both worked at it and it came to me. It wasn't at the end of the process. I still had stuff I had to go back and tie up. There was a certain point where I realized where it was all going. That was a great relief. It still took a lot of rejiggering and making it fit. The blacks... each chapter is encased in black. The unconscious surrounds each chapter. I like looking at the book sideways and seeing these little demarcations.

SPURGEON: You've talked about wanting to do memoir, but was there ever any reluctance to work in that form that went along with that desire? You worked in fiction for so long

. Was there a process to getting to where these reality-based works had more value to you? Was there any bias to overcome?

BECHDEL: In a way, I don't even think of

Dykes To Watch Out For as fiction. It's not that it was autobiographical in any strict sense, but I was always trying to write about people who had lives like me and my friends. Almost like a non-fiction project, like I was reporting even though I was making it up. And over the years of doing

Dykes To Watch Out For, I did start doing various little autobio experiments. I did

an issue of Gay Comix in 1993 where I wrote a lot of stories about myself. That was really fun. I enjoyed that so much. That was sort of an awakening, that I wanted to do more of this. I realized that to do more of that meant telling this foundational story about my family -- my dad, his suicide and his closeted gayness. That took me a long time to figure out how to do. Once I did it I was like, "This is my medium. I love this."

I was invited to speak at a non-fiction conference at the University of Iowa's non-fiction program -- like a master's degree. And it was

so cool. There was this thrill of recognition that I had felt when I was a young lesbian meeting other gay people. These are people that are writing about the actual world. These are my people.

SPURGEON: So you feel common ground with other memoirists.

BECHDEL: Oh, I do. I was very, very influenced by

Robert and Aline [Crumb], by

Harvey Pekar -- that was the stuff I was reading in my 20s, those formative years. And all the other autobiographical stuff that has spun off of them.

Joe Matt, and

Joe Sacco's autobiographical stuff. I've read it all. In fact, for a long time I thought that's what comics is -- people writing confessionals about their masturbation or pornography addiction.

SPURGEON: That sounds like the ad campaign we've all been waiting for, Alison. [laughter] "This Is Comics."

There's something that you say in the work, where you're talking about Dykes

, and the changing context in which that work was received as more and more depictions of those kinds of lives became more settled into mainstream media. What struck me is that your shift is into another area that may be even more populated -- even cartoon memoirs of a book-length variety are popular now. Does creating a work where there's a lot of that kind of material out there, is that a hindrance? A boon? Is there a fashionable

quality to these last two books that maybe benefited you? Do you worry about coming out on the other side of this trend?

BECHDEL: I've very much benefited from the trend of memoirs, and graphic novels, and graphic memoirs. The fact that those things are appealing to people for whatever reason has basically made my career. I don't feel like I was doing them for that reason. This is just the work I want to do. So I haven't thought about this as too many people doing it and -- I haven't thought about that. I will now, though. [laughter]

SPURGEON: There's a sense in the book that you do a little thinking about where you're heading. How it positions you. I wondered if you were the kind of person that might even push away from a certain kind of work because it's something you've done or something that's being done.

BECHDEL: I don't feel like I've made those kinds of calculations in my career. [laughs] I'm not that smart. I've always pretty much worked comfortably inside some existing format. With

Dykes To Watch Out For I was doing this alternative weekly format. It was pushing boundaries in the sense of its content, but not in any other way. Even with

Fun Home there were precedents for that kind of work.

The one thing I do feel committed to is that over the years I feel like I've become a little more formally adventurous. I do have some desire to push the boundaries of what comics can do. So far for me it's been -- what has it been? -- telling complicated stories, but having them still be situated in the world of comics. And for me that has meant not just telling stories about my life but bringing in this other material. Psychoanalysis. Virginia Woolf. That feels exciting, to push at what you can talk about comics. I haven't become ambitious until quite late in my career.

SPURGEON: The Donald Winnicott material in

SPURGEON: The Donald Winnicott material in Are You My Mother?

, that would seem to indicate you'd be very effective at biographical work. In fact, there are elements in your work that might indicate a number of potential paths for you. When we talked about Fun Home

making an impression on what you might do next, it seems that now there are two books that might lead to a third. It also might free you up, though. Do you feel the freedom to go wherever you want now? Are you freer on this side of Are You My Mother?

than you may have felt going into it?

BECHDEL: Yes. I do feel freer. And I'm committed to my next project being easier and lighter than the stuff I've been doing. I need a break. I miss doing humor. I get frightened talking about humor because I feel once I start talking about I'm not going to be able to do that. I have an idea for something that will still be autobiographical but also funny and light. As opposed to these searching family explorations.

SPURGEON: Do you ever feel the pressure to tamp down your humor? Maybe on this work in particular. There are a few funny moments, but I wonder if it's ever an impulse of yours to go heavy in that direction.

BECHDEL: No. I feel like

Fun Home there was a lot of humor, but in this book about my mother there's not much humor at all. It goes with the territory of this difficult topic. I feel like I would like to do humorous stuff again.

*****

*

Alison Bechdel

*

Are You My Mother? at a major, on-line bookseller (it's available everywhere, but I can't find a publisher's page for it)

*****

* a panel featuring one of the many conversations in

Are You My Mother?

* photo of Bechdel by me; I think that may be 2009

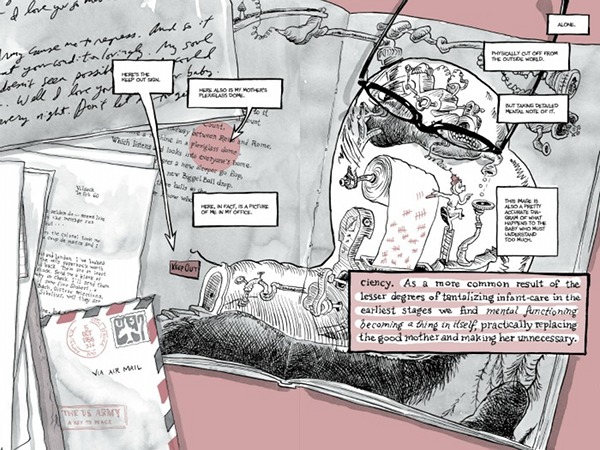

* one of the complicated page spreads in

Are You My Mother?, with different visual references and employments of text

* one of the "flashback" sequences in

Are You My Mother?

* a more standard page, but note the shifts in staging

* Bechdel's use of highlighted text

* that page with the funny three-panel description of Bechdel's view of God and the universe

* Winnicott and Woolf

* I just like this panel (below)

*****

*****

*****

posted 4:00 am PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives