June 20, 2010

CR Sunday Interview: Gene Luen Yang

CR Sunday Interview: Gene Luen Yang

*****

It's been only a few years since

Gene Luen Yang roared to a kind of cartooning success emblematic of new ways of fashioning a comics career. His

American Born Chinese became the first graphic novel

to receive a nomination for a National Book Award (in the young people's literature category). The book would go on to win

the ALA's Michael L. Printz award for young-adult literature, another first. It also sold like the dickens throughout. I don't know anyone who didn't root for Yang when he was picking up the honors, and I know few people interested in the world of comics that haven't tracked his attempts to build on that rush of success since.

Yang followed up

American Born Chinese with the more difficult, complex, short-story collection

The Eternal Smile (with friend and fellow major talent

Derek Kirk Kim), and now

Prime Baby, which was

the last feature to appear in the New York Times' run of comics in its Sunday Magazine. I thought

Prime Baby very charming when I picked up the recent collection, and took the chance to contact Yang so we could maybe go back and forth a bit. I'm glad he agreed. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: I don't want to give you as impossibly as broad a first question as how

TOM SPURGEON: I don't want to give you as impossibly as broad a first question as how American Born Chinese

might have changed your life, but I wonder how such a big and obvious success on the resume might have had an impact on the way you work. Was there any time at all where it might have felt like a hindrance to work under that book's considerable shadow? Do you feel like there are expectations for your work that might not be been there before?

GENE LUEN YANG: Well, there are expectations in that more than my mom and my cartoonist friends read my comics now. To be honest, I do feel some pressure. I think a lot of it comes from the advance system that the book industry uses, that the comics industry is slowly adopting. Not to complain about the money that a publisher is willing to invest in me, but with money comes pressure. If you make a sucky mini-comic, nothing really prevents you from making your next mini-comic. If I lose a lot of money for my publisher, I don't know... I can't imagine them wanting to continue giving me advances.

Practically speaking, the success of

American Born Chinese has allowed me to devote more time to making comics. I've been able to go part-time at my day job, so I get 2-3 full days each week at my drawing table. I used to have to do comics in the early morning, at night, and on the weekends.

SPURGEON: For that matter, have you been able to fully enjoy that book's success, do you think? Now that you've had a couple of years, is there anything about the experience in terms of how well that book did that stands out to you?

SPURGEON: For that matter, have you been able to fully enjoy that book's success, do you think? Now that you've had a couple of years, is there anything about the experience in terms of how well that book did that stands out to you?

YANG: Sure, I've been able to fully enjoy the success of

American Born Chinese. I got to go to

Angouleme with my French-speaking editor

Mark Seigel. I got to go to Washington D.C. for the

National Book Festival. I got to serve as a judge for the

National Book Awards last year. I got to be a special guest at

Comic-Con. I got to shake

Neil Gaiman's hand when I accepted the

Eisner. If you told me five years ago that American Born Chinese would result in any one of these things, I would've laughed myself silly. But for all of them to happen? It's so amazing that it almost feels like some kind of practical joke.

I remember being really worried right before my panel at Comic-Con that no one was going to show up. It's happened before at book signings and such. I did this one at my local Borders after the NBA nomination that was like that. The staff were really nice. They put out this coffee/frosty/smoothie-type drink in little sampler cups on my table, and they had a beautiful display of my books in the corner. One person came up to talk to me. Nobody asked me to sign. Several people waited until I wasn't looking in their direction to sneak a sampler cup.

But the Comic-Con panel was totally different. People showed up. A lot more people than I expected. They asked great questions and seemed genuinely interested in my comics. An experience that stands out? That was probably it.

SPURGEON: You probably did the healthiest thing available to you as a same-publisher follow-up to ABC in that

SPURGEON: You probably did the healthiest thing available to you as a same-publisher follow-up to ABC in that The Eternal Smile

was almost radically different -- in fact, the short stories in that book all break in different directions from each other, let alone from past work. Was that a satisfying work to put together, these different stories in different modes and with different tones, all in color, after such a sustained graphic novel effort? It looked like you guys were having fun but at the same time I could also see the book as being laborious in terms of its execution.

YANG: We were having fun. Eh. I should say, I was having fun. It was laborious, but Derek was the one providing all the labor. All I had to do was send him a script and then wait for these incredible pages to show up in my inbox.

Derek is one of my closest friends, so working with him is always fun. "Duncan's Kingdom," the first story in

The Eternal Smile,

was originally published by Image Comics in the late '90s as a two-issue mini-series. At the time, Derek was going through a bout of writer's block. He told me he wanted to draw some fantasy-type stuff, but couldn't think of a story. He asked me to write for him and I jumped at the chance.

We both eventually moved on to our own projects, but "Duncan's Kingdom" had a special place in our hearts. When we got hooked up with First Second, we wanted to collect "Duncan," but it was too short to stand on its own. We fleshed it out with two more stories dealing with the same theme and ended up with

The Eternal Smile.

I'm very proud of the work for the reasons you mentioned. It's the most beautiful book I've ever worked on, mostly because Derek handled all the visuals. I got to experiment with different writing voices because I knew Derek's art could embody the differences in a way that my own art could not. He really did an amazing job.

SPURGEON: There are what I would say are obvious cautionary elements to

SPURGEON: There are what I would say are obvious cautionary elements to The Eternal Smile

in terms of how it presents fantasy vis-a-vis reality. What I couldn't tell -- and maybe you don't want to tell -- is where your personal sympathies lie. Is it enough to pick up a kind of critical ethos to the stories in that book, or is there a specific criticism of fantasy and its limits you'd like the reader to consider?

YANG: I think "Duncan's Kingdom" is particularly anti-fantasy. I'm a geek and I've certainly consumed more than my fair share of fantasy pop culture. "Duncan's Kingdom" might've been the result of geek self-loathing, that feeling you get after you've missed four consecutive meals because of videogames or when you realize that for the amount of money you spent on comics you could've bought a decent car.

As I've gotten older and less involved in fantasy pop culture as a consumer, I've softened in my self-loathing. Years ago, I had a student in one of my programming classes who never said a word. Whenever I asked him a question, he would look down at his feet and mumble. I used to keep the computer lab open after school, and this kid would come in regularly to work on his projects. We started talking.

I remember the conversation when he lost his mumble. He told me that he played one of those online fantasy games,

World of Warcraft or

EverQuest or something like that. Supposedly, in that game he was The Man. He was awesome at killing dragons or whatever, and he ran a guild that was made up of players who were much older than him, 20- and 30-somethings. When he talked about that game, he got this confidence in his voice that I hadn't heard before. He became a guild leader. He became The Man.

That was my first real experience of one of those benefits of fantasy culture that fantasy apologists are always talking about. But it's true. Those leadership skills and that confidence were always in my student. It just took a videogame to bring it out. As he got older, more and more of his dragon-killing guild-leader self emerged in his real life.

I see that a lot as a teacher. A lot of students find their confidence in some sort of subculture. Maybe it's anime club or a sports team or some sort of virtual environment. They find their voice there, and as they get older they learn to bridge the gap between that subculture and the wider world. They bring their confident alias out into the open.

That was in the back of my mind when I was writing "Urgent Request."

SPURGEON: I'm really fascinated by the use of white space in "Urgent Request." Supposing that was your contribution, is there a thematic component in terms of the isolation the character feels, or were you perhaps more interested in how that imagery floating in space read? How cognizant are you of page design and the quality of the experience of reading that you're offering an audience?

SPURGEON: I'm really fascinated by the use of white space in "Urgent Request." Supposing that was your contribution, is there a thematic component in terms of the isolation the character feels, or were you perhaps more interested in how that imagery floating in space read? How cognizant are you of page design and the quality of the experience of reading that you're offering an audience?

YANG: Man, I wish I could take credit for that, but the white space was all Derek. I write in thumbnails, and the script I gave him was basically laid out on six-panel grids. He told me he wanted to try out this technique that was inspired by Chester Brown, where he'd draw all the panels first and then lay them out on the pages. He thought it would make for more controlled pacing. He was right. In that story, the white space becomes a part of the storytelling voice.

SPURGEON: I want to make sure to ask a bunch of questions about

SPURGEON: I want to make sure to ask a bunch of questions about Prime Baby

, which is the book that made me send you an e-mail. First of all, this was one of the New York Times Sunday Magazine Funny Pages comics, the last one if I'm not mistaken. I don't know anything about how that project worked. How were you contacted? How much editorial back and forth was there between that time and when the work began to be printed? Did you enjoy the process of making the book?

YANG: Yep, it was the last one. They canceled the feature after my story finished.

The

New York Times contacted my agent, my agent asked me, and I said yes because, you know, it's THE NEW YORK FREAKING TIMES. There was some editorial back and forth in the beginning. I proposed one or two story ideas that they didn't think was appropriate for the paper before landing on

Prime Baby. Originally, I wanted to do a story about a porn addict who is visited by leprechauns.

SPURGEON: [laughs] So what ended up being your interest in doing Prime Baby for this gig? Was this a story you'd been thinking about doing or is this something that was more of a direct response to the specific publishing opportunity?

SPURGEON: [laughs] So what ended up being your interest in doing Prime Baby for this gig? Was this a story you'd been thinking about doing or is this something that was more of a direct response to the specific publishing opportunity?

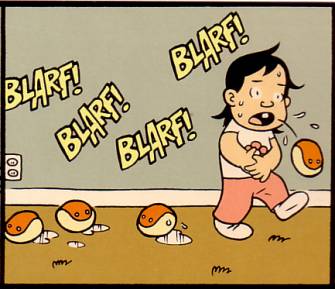

YANG: Prime Baby was a direct response to the

New York Times gig. It came from three different sources. First, my wife and I had recently had our second child and we were dealing with sibling rivalry at home. Second, I assign this prime numbers exercise to my programming students every year, and they often ask what the point of prime numbers is. Finally, I wrote this short story a couple of years ago about a baby who spoke in prime numbers. I used to do 15 minute free-writes as a way to warm up before scripting something, and the short story was the result of one of those free-writes.

SPURGEON: Were you aware of what other cartoonists had done in the series by the time you were working on Prime Baby

? Was Prime Baby

in any way a reaction to what had previously been published?

YANG: I'd read both

Jason's and

Seth's stories. Prime Baby wasn't a conscious reaction to them, but I felt very, very intimated about being in a space they'd once occupied. They're very different from each other, but they're both so polished, you know? And they both have these deep, effecting storytelling voices. Actually, maybe the "lightness" of

Prime Baby was a reaction to them. I knew I couldn't compete in the same ballpark.

SPURGEON: You mention lightness... I think more than any of the other comics that ran in the Times, yours was humorous in a way that we think of comic strips being humorous: was that intentional? Are you a strip fan, is that a mode of expression that you enjoyed inhabiting for a while? Were the constraints of the strip useful to you as a creator in any way?

SPURGEON: You mention lightness... I think more than any of the other comics that ran in the Times, yours was humorous in a way that we think of comic strips being humorous: was that intentional? Are you a strip fan, is that a mode of expression that you enjoyed inhabiting for a while? Were the constraints of the strip useful to you as a creator in any way?

YANG: I love comic strips the way the vast majority of people love comic strips. I read them whenever I can. I have a couple of collections of

Calvin and Hobbes at home. I just don't obsess over them like I do long-form comics.

I realized long ago that I am not a strip cartoonist. I can't handle the pressure of having to be funny every three panels.

That said, I do rely heavily on the rhythm of the page turn when I write comics. I try to have something that entices the reader to turn each page, maybe a question to be answered or a mild punchline. My love for the page turn is why I'm reluctant to do Scott McCloud's Infinite Canvas thing, despite being a computer nerd and very McCloudian in my thinking about comics.

Doing a comic for the

New York Times was difficult. Those were the most constraints I'd ever had on a project. Each page had to essentially function as a chapter, and I had to have between 18 and 20 chapters, no more and no less. I learned a lot from that project, and I have renewed respect for cartoonists working in formats that are determined by someone other than themselves.

SPURGEON: In collected form, Prime Baby

has this sort of bouncy energy that makes it hard to remember that it was ever serialized. Was it hard for you at all to maintain what you were doing over the life a serial strip, even a relative short serial like this one?

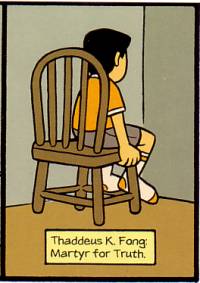

YANG: Some of the pages are definitely bouncier than others. I guess that's true of any work. Thaddeus's voice was pretty loud in my head, so coming up with all the jerk-ish dialog wasn't hard. Getting everything to fit into an 8" x 8" square was.

SPURGEON: Is there anything to the way you construct the individual pages that's important on a project like this one? For instance, is it important that every individual story segment have a certain sort of gag, or that certain characters are voiced every time out? What is the intended effect of so much dropped detail in your panels, how so much of Prime Baby takes place against a single-color background?

SPURGEON: Is there anything to the way you construct the individual pages that's important on a project like this one? For instance, is it important that every individual story segment have a certain sort of gag, or that certain characters are voiced every time out? What is the intended effect of so much dropped detail in your panels, how so much of Prime Baby takes place against a single-color background?

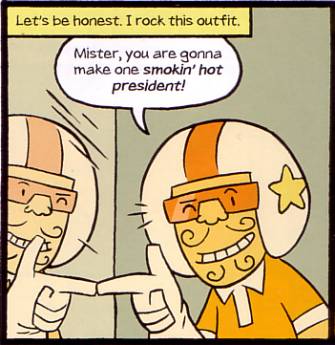

YANG: I have a pretty simple style to begin with, but the visuals of

Prime Baby are especially simplistic. I drew dots for the eyes and very few background details. All those decisions were a response to the limited space. Thaddeus is a pretty wordy kid, at least in his own thoughts, so the pages would already be crowded with text. I was worried that competing details in the images would be off-putting to the reader, so I simplified even more than I normally do.

SPURGEON: How much sympathy do you have for Thaddeus? He's a comically disagreeable character in a lot of obvious ways, but you're also upfront about him working from these positions of real pain and fear. Plus it ends up he's largely right.

SPURGEON: How much sympathy do you have for Thaddeus? He's a comically disagreeable character in a lot of obvious ways, but you're also upfront about him working from these positions of real pain and fear. Plus it ends up he's largely right.

YANG: Derek tells me that of all my characters, Thaddeus is most like me in real life. I'm not sure how to take that. I tried to build sympathy for Thaddeus, both in my reader and myself, by making him relatively young. When a third grader suggests that his baby sister needs to be dissected, it's kind of funny. If a sixth grader were to do it, you'd want to call in the professionals.

I do like him a lot. As I said before, his voice is very clear to me. I hope to use him again in a future project. I've been batting around a couple of ideas in the back of my head as I've worked on my other stuff, but I don't have anything concrete yet.

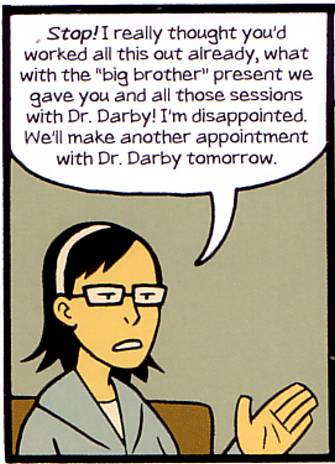

SPURGEON: Is it fair to see the strip as critical of a certain kind of parenting? The parents seem to accept Thaddeus' apparent similar state a bit too quickly for me.

SPURGEON: Is it fair to see the strip as critical of a certain kind of parenting? The parents seem to accept Thaddeus' apparent similar state a bit too quickly for me.

YANG: Yes, it's fair. I think modern parents are encouraged to over-parent in this very... I don't know...

chic way that tries to hide the real difficulty of parenting. I'm particularly susceptible to over-parenting because I tend towards paranoia, especially where my kids are concerned. I feel the pressure to read the latest studies on nap time and buy the latest BPA-free bottles and install the latest organic car seats.

But you can do all this stuff and still find that a grumpy baby is a pain in the butt. New technology doesn't relieve parents of the hardest parts of parenting, but as modern people we sort of expect it to.

Thaddeus's parents are a send-up of modern parents. I don't know how much of it comes through the final pages of Prime Baby, but I definitely had all this in mind when I was writing those two characters.

SPURGEON: The Sunday Times Magazine was a humongous platform for any comics work. Did you hear back from people as the comic was serialized? Did what you hear have any effect on how you presented the print collection?

SPURGEON: The Sunday Times Magazine was a humongous platform for any comics work. Did you hear back from people as the comic was serialized? Did what you hear have any effect on how you presented the print collection?

YANG: I did hear back from some folks. There were some prime number fans who wrote me, and some parents of kids named Thaddeus. It was pretty much all positive feedback. I suspect that the folks who didn't like it were not passionate enough in their dislike to write me about it. That has not been true for my other comics.

Reader feedback didn't really have an effect on the print collection at all. The presentation of the print collection was designed by First Second, with some input from me. They did an amazing job, in my opinion.

SPURGEON: Has anyone blamed you for killing that feature, Gene?

YANG: I asked the

Times folks over and over again about this and they've assured me that it's not my fault. But I have my doubts. Thanks for bringing it up, Tom.

SPURGEON: Your Airbender boycott: were you comfortable using your comics-making skills in that fashion? I thought that mode of presentation really suited your style, but I wondered if you felt that way. When you do a comic like that, do you think in terms of changing minds or is it more about the personal satisfaction of staking out a position that important to you, no matter what others think? How controlled a piece of rhetoric is that comic?

SPURGEON: Your Airbender boycott: were you comfortable using your comics-making skills in that fashion? I thought that mode of presentation really suited your style, but I wondered if you felt that way. When you do a comic like that, do you think in terms of changing minds or is it more about the personal satisfaction of staking out a position that important to you, no matter what others think? How controlled a piece of rhetoric is that comic?

YANG: For that one I used my teacher-self (which is basically me doing my best Scott McCoud impression) because the strip is about teaching rather than arguing. I wanted to raise awareness about a particular issue without beating the reader over the head with it. Righteous indignation is really, really fun, but there's just too much of it these days, you know? I wanted to share my line of thinking while respecting the reader's decisions and free will.

SPURGEON: Gene, I have no idea what you have coming up in future months. Is there a next major project?

YANG:

YANG: I've got a few things in the works. Early next year,

First Second will be releasing a graphic novel I did with

Thien Pham, a fellow Bay Area cartoonist. Thien is actually one of three cartoonists teaching at my school, so we see each other pretty regularly. (

Brianna Miller is the third.) Our project is called

Level Up, and it's about a videogame freak who gets a divine calling to go to med school. I handled the writing and he handled the art. This one has been a long time coming. It was originally called

Three Angels and slated to come out the year after

American Born Chinese, but the story was sucky so we redid it. I've written more drafts of this story than any of my other ones. After American Born Chinese started getting some attention, I freaked out a little bit because I realized that I'd been constructing my stories on pure instinct. I never really understood story structure. So I read a bunch of books on story and plot and character and wrote

Three Angels. It was a stiff and terrible thing. I'm much happier with Level Up.

I've also been working on a historical fiction project about the

Boxer Rebellion in late 19th Century China. In the early 2000's, Pope John Paul II

canonized a couple hundred Chinese saints. These were the first Chinese ever to be canonized by the Catholic Church. The church I grew up in, a Chinese Catholic Church in the South Bay, made a big deal out of this, naturally.

I looked into these saints and discovered that many of them were martyred during the Boxer Rebellion. These Chinese Catholics were killed by the Boxers -- poor Chinese peasant boys who were angry at the European presence in China -- because the Chinese Catholics were seen as traitors to their own people for embracing a foreign faith. The Communist government in China actually protested the canonizations on these grounds.

I found that this historical conflict embodied a conflict Chinese and Asian Christians sometimes feel between our cultural heritage and our faith. As I read more about both the Boxers and the Chinese Christians, I became less and less clear about who to root for. So that's what this project is about. It will be two different graphic novels. The first will feature the Boxers as the protagonists and the second the Chinese Christians. There will be shared characters. I'm writing and drawing everything myself, and

Lark Pien has agreed to color it. I've already been working on it for a couple of years. I'm about 3/4 of the way through the first volume. It's just taking forever.

Finally, I've been invited to contribute to

the next volume of Strange Tales from Marvel Comics. I'm really excited about that. I'm doing a short four-pager for that.

*****

*

Prime Baby, Gene Luen Yang, First Second Books, hardcover, 64 pages, 1596436506 (ISBN10), 9781596436503 (ISBN13), April 2010, $19.99

*****

* cover to First Second's

Prime Baby collection

* two panels from

American Born Chinese

* cover from

The Eternal Smile

* panel from "Duncan's Kingdom"

* page from "Urgent Request"

* seven panels from

Prime Baby hopefully appropriate to the conversation at hand

* panel from Yang's formal

Last Airbender boycott comic

* panel from forthcoming

Level Up

* one more panel from

Prime Baby (below)

*****

*****

*****

posted 10:00 am PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives