July 7, 2007

CR Sunday Interview: Jeet Heer

CR Sunday Interview: Jeet Heer

*****

Jeet Heer is one of the leading lights among writers writing about comics for mainstream publications, and one of the first writers to assemble an impressive client list for such articles. He has since put that journalistic impulse into the service of writing essays for collections of classic comic strips. In addition to two pieces for the

Krazy & Ignatz series at Fantagraphics, Heer is currently co-editing and providing the massively rich introductions to the

Drawn and Quarterly Gasoline Alley books. The

Gasoline Alley work and his introductory essay to the recent

Clare Briggs reprint effort

Oh Skin-nay are the main subjects of this interview. I'd like to thank the very busy Mr. Heer for his time, and

Tom Devlin at D&Q for providing samples of art.

*****

TOM SPURGEON: Did you read comics when you were a kid? At what point did your interest in comics intensify closer to what it is today?

JEET HEER: My history with comics has some peculiar local coloration but it also follows a common trajectory. I was born in India in 1967 and moved with my family to Canada when I was five years old. My first language was

Punjabi. To help us learn English, my father gave me and my brother comics from the

Amar Chitra Katha series, published by

India Book House. Virtually unknown in the West, these comics can be described as

Classics Illustrated with a

masala flavor. In classic comic book style, they recount stories (both mythological and historical) from India's past. This series is published in many languages; the ones I read were in English. So the books served as a bridge between the old world and the new, letting me learn about India's history in the language of my adopted homeland.

Apart from this parental gift, I started reading a lot of comics when I was six or seven:

Peanuts and

Beetle Bailey in the newspaper as well as comic books like

Uncle Scrooge,

Archie, the

Charlton horror line,

Superman and

Batman. A desire to master English was a big part of what made comics attractive; they seemed like a fast-track to literacy. The school board had labeled me a "remedial reader"; ashamed of this stigma, I tried to learn as much English on my own as quickly as I could.

I quickly morphed into your typical teenage geek of the comic book fan genus: over-weight, no athletic prowess, too shy to talk to girls, an easy prey for bullies, and possessing an encyclopedic knowledge of the

DC and

Marvel universes. That part of my history is of course fairly familiar, replicated in the lives of millions.

What perhaps made me a little bit different is that I also had an interest in the broader history of comics, extending to comic strips and magazines like

The New Yorker. Partly this was because I was also a history nerd and loved anything that hailed from the early 20th century, be it

Buster Keaton's virtuoso pratfalls or

Robert Johnson's hypnotic voice. It was a matter of timing. The 1970s saw the blossoming of the modern nostalgia industry, so at bookstores and libraries you could see thick volumes reprinting the best of

Buck Rogers,

Dick Tracy and

Orphan Annie.

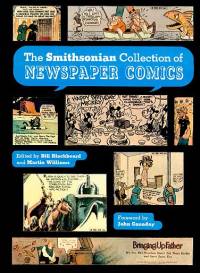

An absolutely pivotal experience for me was first encountering, while still coping with the onset of puberty,

The Smithsonian Collection of Newspaper Comics (edited by

Bill Blackbeard and

Martin Williams). For me this is a volume almost as important as the New Testament or the Koran. It's where I first encountered

Krazy Kat,

Little Nemo,

Polly and Her Pals,

Gasoline Alley and countless other treasures. The book gave me my first sense of how great the early comic strips were, a lost Troy waiting to be excavated.

Popular histories by

Jules Feiffer and

Jerry Robinson also whetted my appetite for old comics. Later on, I pored over

The Comics Journal and

Nemo, along with the reprint volumes published by Richard Marschall, Bill Blackbeard,

Dean Mullaney,

Cat Yronwode, and

Denis Kitchen.

Living in Toronto made it easy to be a comic scholar/nerd: The Dragon Lady comic book store (as you can guess by the name) was run by a fan of old comic strips. The store published its own magazine line which reprinted many classic cartoonists (including

Roy Crane and

Harold Gray). Soon after, there was

The Beguiling, one of the world's great comic book stores, which stocked anything I could care to read. A good comic book store is as beneficial as a good teacher: it can help guide and nurture your taste. Reading alternative cartoonists like

Robert Crumb,

Kim Deitch, and

Seth only reinforced my interest in comics history; so many of the best current comics were done by artists steeped in the past.

SPURGEON: How did you end up writing about comics? How much of your professional time is currently devoted to comics-related writing and projects?

HEER: Well, there are two sides of this, since I write about comics both as an academic and as a journalist. When I went to grad school, I decided to do my doctoral thesis on Harold Gray's

Little Orphan Annie, a great comic strip that offers a chance to say something new about the history of American conservatism. To support myself through grad school, I've worked as a cultural journalist for newspapers like the

National Post and the

Boston Globe, as well magazines like

The Virginia Quarterly Review and

Slate.

When pitching ideas, I found the newspaper and magazine editors, having grown up on comics and wanting strong visuals for their publications, were receptive to articles about cartooning. This was about five or six years ago, at the beginning of the graphic novel boom. So a good chunk of my journalism (about a third) has been comics-related, although I also write extensively on literature, film, and politics. Actually, the most widely read article I ever wrote was on the political philosophy of

Leo Strauss, a subject far removed from comics. Right now, because I'm devoting myself to my thesis and book projects, almost everything I write is about comics, but that will change when I return to a more normal routine. I'd like to settle for writing half on comics, half on the rest of life.

SPURGEON: How do you feel the audience has changed for writing about comics since you've been doing it? Is your own writing different to reflect any perceived changes in the audience? Are you able to write more sophisticated and longer pieces now, for instance?

HEER: When I first started writing, every article had to be introductory and rudimentary. You know the genre: "POW! BAM! Comics Aren't Just For Kids Anymore." That's really changed in the last two to three years. You can expect readers to know about

Maus now, so you don't have to start with a potted history of comics or justify why you are writing about comics in the first few paragraphs. The pleasure of writing longer articles, like my 7000-word essay on

Winsor McCay for

The Virginia Quarterly Review, is that you can get even farther away from elementary writing and explore topics in depth. I've noticed that other writers are doing this as well:

Sarah Boxer in the

New York Review of Books and

Douglas Wolk in

Salon. It's a welcome trend, showing a more receptive and sophisticated audience.

SPURGEON: Can you tell me how your involvement in the

SPURGEON: Can you tell me how your involvement in the Gasoline Alley

project came about?

HEER: There is a short version and a long version. The short story is that

Chris Oliveros liked my newspaper writing and asked me to write the introductions for the series.

The long story goes back to the

Smithsonian book mentioned earlier.

Joe Matt was born in 1963;

Chris Ware and I in 1967. When the three of us were growing up, Frank King was a virtually forgotten figure. Comic strip fans of the 1970s had an entirely skewed sense of history: they tended to be aging man-boys who wanted to reread the adventure stories of their youth. They doted on

Hal Foster's anatomical accuracy,

Milton Caniff's cinematic storytelling and

Alex Raymond's flowing drapery. What they tended to dislike and ignore were the cartoony cartoonists who told stories that were funny, warm and human:

Segar's Popeye, Gray's

Annie, King's

Gasoline Alley, and Herriman's

Krazy Kat. The Smithsonian book changed all that.

Separately, but around the same time, the three of us read the Smithsonian volume and it blew our little minds. Right from the start, my favorite comic in that book was the Sunday page done in woodcut style where Walt and Skeezix go for a walk in the woods. From that point on, Chris and Joe started to collect all of King's art and I started researching the history of American comics. Eventually Joe convinced Chris Oliveros that King's work deserved reprinting. Because Chris Ware and I had already done a great deal of research, we were ready to take on the project. Everything came together beautifully. The seeds that Blackbeard and Williams planted bore fruit.

SPURGEON: At what point did you decide on such lengthy introductions?

HEER: Right from the start, Chris Oliveros wanted me to do long introductions. But to be honest, when he first contacted me, I didn't know if there was going to be enough I could write about King's life and work. What changed my mind was a trip I took in the summer of 2003 with Chris Ware and Chris Oliveros to meet Drewanna King, the grand-daughter of the cartoonist. Lucky for us, it turned out Drewanna was devoted to her family's history. She was an avid genealogist and pack-rat. Her basement was jam-full of King goodies: original art, photos, diaries, and letters. With great generosity, Drewanna shared not only her family treasures but also her memories. Meeting her convinced me that I could write about King's life at length, in a way that would enrich the reading of his comic strips. King was essentially an autobiographical artist, so facts about his life deepen our appreciation of his art.

I should add that in writing the introductions, I always work closely with Chris Ware. Aside from his well-known gifts as a cartoonist and book-designer, Chris has several hidden talents. He's an excellent editor, with a strong narrative sense of how to unfold a story. So Chris and I discuss a great deal how we want King's life story to slowly reveal itself to readers.

SPURGEON: What is the process for selecting, researching and then putting together the introductions? For instance, for volume 3, how did you settle on licensing as a topic, and how did the material come together that was photographed for that section? Are you drawing from one collection? Many?

SPURGEON: What is the process for selecting, researching and then putting together the introductions? For instance, for volume 3, how did you settle on licensing as a topic, and how did the material come together that was photographed for that section? Are you drawing from one collection? Many?

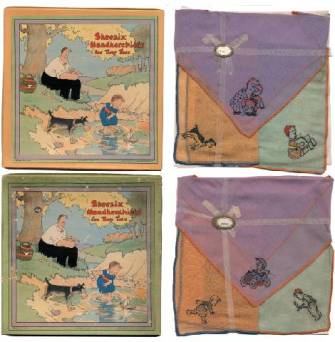

HEER: I try to make each introduction reflect something that happens in the years being reprinted. For example, the merchandising of Walt and Skeezix took off around 1925. So for the current volume, which reprints the strips from 1925 and 1926, I made licensing the main topic. The main source for this introduction is the private collection of Chris Ware, which of course made it easy to photograph. So far, we've relied on a few collections: Drewanna King, Chris Ware, Joe Matt, and others. There are other collections waiting to be tapped for future volumes, so I'm not afraid of running out of material.

SPURGEON: Tell me about your involvement in the Briggs/Nesbitt book and how that developed into a stand-alone project.

HEER: Again, a short answer and a long one. To be brief, Tom Devlin bought a copy of

Oh Skin-nay; he loved the book and found out it would be feasible to republish it. He tapped me to do the intro.

The more verbose answer would go like this: I became interested in Briggs because he was a mentor to Frank King. Aside from Richard Marschall, most comic strip historians haven't given any attention to Briggs, which is a shame. He was immensely popular in his time, and his work remains fresh and alive. Because of the affinity between King and Briggs, it made sense for Drawn and Quarterly to do the book, and for me to write a biographical essay.

Along with

Walt and Skeezix, I hope the Briggs book will help rewrite the history of comics. I really want to challenge the canon that exalts illustrators like Hal Foster and Alex Raymond. To me, the great comic strips aren't

Prince Valiant,

Flash Gordon, and

Buck Rogers. I much prefer

Gasoline Alley and

Oh Skin-nay.

SPURGEON: The book introduces Briggs as an important figure on multiple tracks: as an influence on multiple school of cartoonists, as a important voice in the new form of humor about marriage, as an artist who worked with nostalgia. Is there an aspect you think most important of all the different things he did?

SPURGEON: The book introduces Briggs as an important figure on multiple tracks: as an influence on multiple school of cartoonists, as a important voice in the new form of humor about marriage, as an artist who worked with nostalgia. Is there an aspect you think most important of all the different things he did?

HEER: For me, Briggs should be remembered as the founder (along with

John T. McCutcheon) of the "Chicago school of cartooning" or perhaps "the mid-western school of cartooning." With his low-key humor, his fidelity to ordinary life, his feel for quiet moments, Briggs created a style of cartooning that was very different from the hurly-burly vaudeville vulgarity of the New York school (

Dirks,

Outcault,

Opper). Briggs's approach influenced not only panel cartoonists like

J.R. Williams but also the whole

Chicago Tribune stable of newspaper strips:

Sidney Smith, Frank King, Harold Gray, and even

Chester Gould. They all owed a debt to Briggs. Thanks to Briggs, mid-century newspaper cartooning became a reflection of middle America.

SPURGEON: What was the appeal of nostalgic work like

SPURGEON: What was the appeal of nostalgic work like Oh Skin-nay

at that moment in time? You see it in writing of that same period, too, these almost blissful reveries about a way of life that seemed to be just past.

HEER: Along with

Mark Twain and

Norman Rockwell, Briggs was one of the great inventors of American nostalgia, the mythos of small town life that still governs the nation's imagination. Briggs belonged to the middle of this trinity: he took inspiration from Twain and mentored Rockwell. In my essay, I try to bring out the paradox of Briggs' life: although his work celebrated the quaint rustic past and he was born in rural Nebraska, Briggs himself was a big-city boy all his adult life. He was a skirt-chaser who hung out at speakeasies and loved playing cards with his uptown friends. But in many ways, the paradox of Briggs was also the paradox of America in the 1920s. The nation had roots in the countryside and small towns, but the real action was in bustling cities like New York and Chicago. So Briggs fit the temper of the times perfectly: he was an urbane man who hankered for a half-imaginary past.

SPURGEON: What has the reaction to the Walt and Skeezix

series been like so far? Has any element of the reaction or any individual response you've heard surprised you?

HEER: The response to

Walt and Skeezix has been extremely gratifying. The first book sold out and went into a second printing. It was reviewed widely and many of the reviews were not just positive but also discerning in their appreciation. To some degree, this came as a surprise. I knew I loved King's work, but I was afraid that a contemporary audience might not like it. Part of me thought that King might be too dated, too much a part of the distant past, to resonate now. Yet both reviewers and ordinary readers responded to King's "ineffable grace and infinite gentleness" (to quote Charles Taylor). I'm happy to say I underestimated the audience of the book and King's ability to transcend his time. One reason why readers responded to King, I now think, is because contemporary cartoonists like Seth and Chris Ware have proven that comics can be subtle. Awakened to the potential of the comics, an audience was ready to rediscover King.

SPURGEON: Are there other projects like this one you'd like to work on?

HEER: I have several projects in the works, but I can't talk about them now. So in lieu of that, I'll list off dream projects that should exist. I'll give not only the name of the project, but the cartoonist who should work on it.

1. The Best of Otto Soglow's The Little King (designed by Ivan Brunetti).

2. The Best of Milt Gross (also designed by Ivan Brunetti).

3. Segar's Thimble Theatre: the pre-Popeye Years (designed by Kevin Huizenga).

4. Floyd Gottfredson's Mickey Mouse (designed by Kevin Huizenga)

5. Jimmy Frise's Birdseye Centre (designed by Joe Matt) -- a great forgotten Canadian strip.

6. Garrett Price's White Boy (designed by Dan Clowes)

7. The Best of Kate Carew (designed by Trina Robbins)

8. The Art of Chester Gould (designed by Charles Burns)

9. The Best of J.R. Williams (designed by David Collier)

SPURGEON: When you're done with the King introductions, what would you most like people to take away from those pieces, and how do you feel they complement the cartoons? Is there any chance they could be compiled into a book?

SPURGEON: When you're done with the King introductions, what would you most like people to take away from those pieces, and how do you feel they complement the cartoons? Is there any chance they could be compiled into a book?

HEER: My goal for

Walt and Skeezix is to create an integrated whole. I want my words to be woven in seamlessly with the other elements of the book: the design, the photos, the comic strips, and the historical notes provided by Tim Samuelson. The effect I'm hoping to achieve is something like a house of mirrors. I want readers to be engaged by the story of

Walt and Skeezix, and then see how the tale reflects aspects of King's life as seen in family photos and diaries. Then Tim's historical notes provide another angle of reflection, so we see

Walt and Skeezix in the context of King's era.

In a weird way, the model for

Walt and Skeezix is

Vladimir Nabokov's Pale Fire. In that novel, you have a long poem (written by a fictional poet), a crazy introduction, and an even wackier explication of the poem, topped off by a sly index. The glory of

Pale Fire is that all these elements play off each other to create a disorienting whole.

Walt and Skeezix is much more sober, but it also tries to be a multi-layered book.

Again, I should emphasize the project is very much a collaboration. Really, the idea of doing the book as an integrated whole came from Chris Ware. I don't think I would have tried to do anything so ambitious if I didn't have his encouragement.

In the future, I might write a full-scale biography of King. But because the introductions to

Walt and Skeezix are so closely tied to the books, I wouldn't just gather my essays together. Rather, I would have to write something fresh from scratch.

*****

*

Oh Skin-Nay!: The Days of Real Sport, Clare Briggs and Wilbur D. Nesbit, Drawn and Quarterly, hardcover, 136 pages, 1894937929 (ISBN10), January 2007, $24.95.

*

Walt and Skeezix, Vol. 3, Frank King, Drawn and Quarterly, hardcover, 400 pages, 1897299095 (ISBN10), July 2007, $29.95.

*****

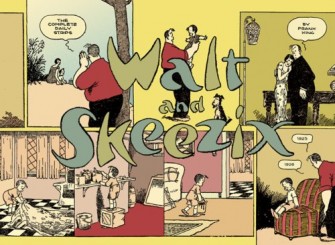

cover image from Walt & Skeezix Vol. 3

the Smithsonian book referenced several times

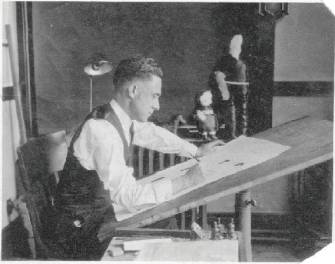

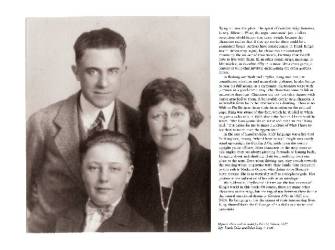

one of the dozens of great historical photos of Frank King throughout the introductions

photo of ancient Gasoline Alley-related toy

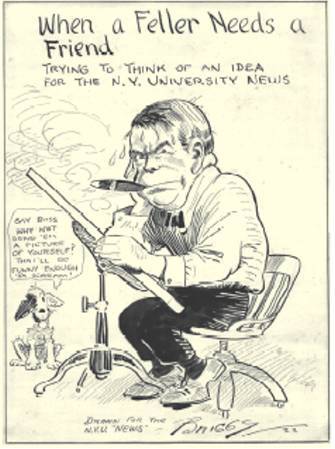

Clare Briggs rarity reprinted in Oh Skin-nay

another Clare Briggs rarity

more licensed merchandise from Heer's introduction -- handkerchiefs and packaging

a page from each project showing how Heer's introductions look (below)

*****

posted 10:30 pm PST

posted 10:30 pm PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives