December 8, 2013

CR Sunday Interview: Karl Stevens

CR Sunday Interview: Karl Stevens

*****

Every year there's one interview at

The Comics Reporter that boasts a difficult production pedigree. This year it was my conversation with the painter and cartoonist Karl Stevens.

Stevens and I talked mid-Summer about his then-recent release

Failure, one of the debut books from the relaunched

Alternative Comics. Stevens had worked with the publisher in its previous incarnation, so in a sense the project was a return home as well as the next book in Stevens' ongoing examination of the lives of young people growing older and slightly roughed up by the exhaustion that settles in after years of resists the monolith of economic necessity.

I think Stevens' work is frequently funny, I like the cultural milieu he's chosen to document, and he's learned to make effective use of his ability to craft stop-and-stare visuals.

Stevens is currently exhibiting work at Carroll and Sons in Boston. I always enjoy seeing him on the road, and I hope he'll forgive me the delay in getting this interview turned around. Please consider a purchase of his book or his work as a stand-in apology on my behalf. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: Are you happy with the book? Is that a weird question to ask? You've done a few of them now. Is it still nice to have a new book in your hands, and to have a work like this out there where people can see it?

KARL STEVENS: Yeah. Absolutely. I definitely have a weird thing in my head where I just want to make a lot of books. I want to have a book coming out every couple of years. If it were up to me, if I could have my way, I'd have one out every year. At this point they're all pretty small press, but it's nice to keep putting product out there.

SPURGEON: You worked with Alternative in their previous incarnation, but is that how you ended up working with Marc Arsenault this time? I'm unclear as to how that relationship was rekindled. I have to admit, I was sort of surprised when it showed up -- I was not aware that you were doing this one with them. How did you end up with the new incarnation of Alternative?

STEVENS: The last book that came out with Jeff Mason was the

Whatever collection, the second book that I did. Marc reached out to me about the backstock of

Whatevers. It was this whole complicated thing. There are a few thousand copies of

Whatever that were at the printer in Quebec. Marc basically contacted to see if I wanted a couple of boxes. So I brought it up to him that I was looking for a publisher for the last collection of the

Failure strips and he was like, "Yeah, sure." [Spurgeon laughs] It was really informal. But yeah, he's taken control of the back catalog, including my books, and translated them into digital form. We're going to do a reprint of

Guilty -- that's the

Xeric book that I did.

SPURGEON: Sure.

STEVENS: I'm going to re-scan those pages, and then fix the spelling mistakes. [laughter]

SPURGEON: I don't think I've ever talked to anyone that was work with Jeff when he kind of... departed the field. Winked out. There wasn't a spectacular crash and burn, it was like Jeff went out for cigarettes and never came back. And he's certainly around, and he has his career in law and he's a supporter of what they're doing down at SAW. But was that a weird circumstance for you as an artist working with that company? Everyone likes Jeff, I like Jeff, and I've not heard of anyone holding a professional grudge on any level with him, but that had to be a unique experience.

SPURGEON: I don't think I've ever talked to anyone that was work with Jeff when he kind of... departed the field. Winked out. There wasn't a spectacular crash and burn, it was like Jeff went out for cigarettes and never came back. And he's certainly around, and he has his career in law and he's a supporter of what they're doing down at SAW. But was that a weird circumstance for you as an artist working with that company? Everyone likes Jeff, I like Jeff, and I've not heard of anyone holding a professional grudge on any level with him, but that had to be a unique experience.

STEVENS: My book was the last book that he put out. [laughter]

SPURGEON: Well, there you go. It's your fault. It's on you.

STEVENS: It's all my fault. [laughter]

SPURGEON: You broke him, after all those books.

STEVENS: Exactly. He was like, "I don't know what to do anymore." [laughs] I remember at the time his wife was going to grad school, and the financials of wanting to keep publishing weren't there. He had to make some decisions about that. Yeah. I hadn't really had an experience with other publishers. Reading all

these tributes to Kim Thompson recently about how he was hands-on as an editor and arguing with

Chris Ware and

Peter Bagge, I could see how you might want that kind of relationship. He was sort of distant by the time he was putting out

Whatever, he maybe had one foot out the door, so I didn't have that kind of relationship with him that he might have had with artists on the earlier books.

SPURGEON: I hope this doesn't look bad in print, because I don't think either of us could ever be mad about the realities of small-press publishing. We know the score. It's kind of a miracle that any books come out.

STEVENS: Yeah.

SPURGEON: So was it weird getting the books back?

STEVENS: You mean recently?

SPURGEON: Yeah, I mean, it's like having an old friend come stay on your couch, at least in a sense. And I guess I further wonder if it was strange at all that at the moment you needed a publisher for this book, this old relationship kind of roars back into view. Lo and behold there are a bunch of Whatevers and this new opportunity.

STEVENS: Marc's been really good about the transition. He's been getting review copies out, he has a couple of people in their with him that do stuff for the books as well.

SPURGEON: Now was Marc hands-on at all in terms of the material?

STEVENS: I'm not much of a graphic designer, and I had a bunch of other projects I was doing, so he basically designed the

Failure book after I provided him with the raw materials. I even said to him, "I don't really care about how it's designed and the package, I'm not much of fetishist about the way it looks."

SPURGEON: Marc's an old-school art director; that's certainly in his skill-set.

STEVENS: Yeah, he's a graphic designer.

SPURGEON: The last book of yours was similarly conceived in that there was a mix of art and some color work in there, and the strips as well, some of which are presented in this form in color. It doesn't strike me as the easiest couple of books to sequence. It's not a bare bones presentation: there's a animating intelligence to it.

SPURGEON: The last book of yours was similarly conceived in that there was a mix of art and some color work in there, and the strips as well, some of which are presented in this form in color. It doesn't strike me as the easiest couple of books to sequence. It's not a bare bones presentation: there's a animating intelligence to it.

STEVENS: Yeah, yeah. As far as the art goes, I did pick images that I thought would work well with the strips. There was a lot of editing. I gave them about 180 pages of material and then it got cut down to about 157 -- so there was a lot of editing in that sense. It was a difficult book for me to conceive because those last couple of years of doing the weekly strip were very random. I went off in about a million different directions. I feel... at the time, I thought that; but looking back at the book it seemed more of a natural thing. It didn't seem as chaotic as it did while I was drawing it.

SPURGEON: You do go off in some different directions, but it seems like there are always through-lines that kind of ground the different paths you take. One thing I wanted to ask you about is that you said that this collection is the last, so I take that to mean it matches up with the last strips you did for The Phoenix before you were let go.

STEVENS: Yeah, this is it. This is all of them.

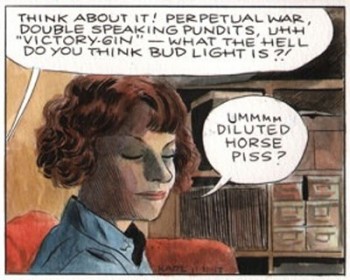

SPURGEON: So the infamous strip that mentions Budweiser in disparaging terms, the one you feel played a role in their letting you go -- is that the last strip that appears in The Phoenix? Because it's one of the last ones here.

STEVENS: There was one more after that. And the book isn't chronological. So the last one was Pope Cat dancing, which was a tribute to Jules Feiffer. I was trying to do Feiffer's dancer with Pope Cat. And failing miserably. [laughs] In the last panel I did have the dancer poke her head in and say something. But that was the last one.

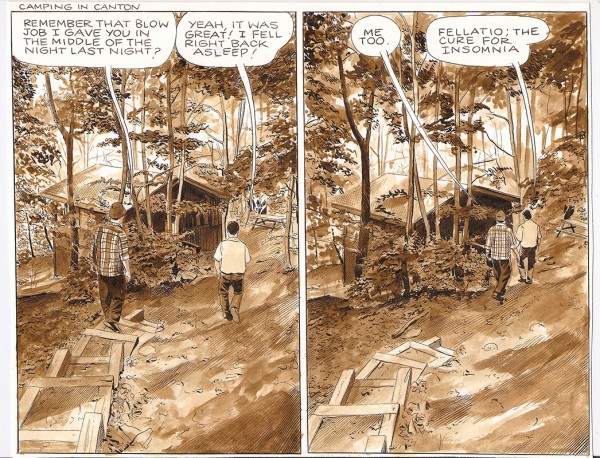

SPURGEON: The bulk of the book, then, is this period of wrapping up your alt-weekly effort. Even though you didn't know at the time when the end would come, there is a definite last day of summer camp vibe in a lot of the strip. It feels like there's a ticking clock off panel. It feels like the last time you'll be depicting certain things, there's an overripe quality to some of the scenes. [Stevens laughs] People complain about being a little older now; the content seems to address the end of

SPURGEON: The bulk of the book, then, is this period of wrapping up your alt-weekly effort. Even though you didn't know at the time when the end would come, there is a definite last day of summer camp vibe in a lot of the strip. It feels like there's a ticking clock off panel. It feels like the last time you'll be depicting certain things, there's an overripe quality to some of the scenes. [Stevens laughs] People complain about being a little older now; the content seems to address the end of something

.

STEVENS: As far as my time at the paper goes?

SPURGEON: As far as the strip's content. I don't know what your platform will look like in the future, but no matter the format it seems like there is something late-period about the content, that you were aware on some level of documenting a period in your life and in the lives of those around you as it came to a close.

STEVENS: Oh, yeah, definitely. There's definitely a sense of that. I would have done it for the next 30 years, just merely because they paid me well enough. It was nice to have that steady gig. But in the back of my head... and always. For most of the run I knew I wanted to do longer stories. I went from doing the Xeric book, which is a longer story to wanting to do something longer and trying to top myself with a longer work. Then they offered me the job of doing this strip. I never lost sight of those longer works. So having this strip was sort of like this albatross, wanting to do these longer stories but not having the time to do it because I was spending all of my time doing this weekly comic.

I think I was just trying to figure some things out.

SPURGEON: It seems like you're basically saying the way you had to work in order to do the strip may not be the way you'd most like to work.

STEVENS: Yeah. Exactly. I'd like to do longer stories, and would like to no longer have certain constraints. Although they did give me a lot of freedom. I got away with a lot, a lot more than most alt-weekly cartoonists.

SPURGEON: You mean in terms of content? Or the indulgence aspect in terms of engaging whatever you wanted to engage how you wanted to engage it?

STEVENS: Both. I just basically had to fill that space. I did it for so long. After

Failure ended I wondered if I should revamp it and pitch it to syndicates, or take it to another paper. But I just felt that I didn't want to commit to it, and that I'm not that kind of cartoonist. I'm not

Keith Knight or

Matt Bors that can put out this consistently brilliant product. I felt my work was to esoteric, too artistic or something.

SPURGEON: What do you mean by saying "artistic"?

STEVENS: There wasn't a theme to it. I was so spoiled to be able to write whatever I wanted to that there was never an overall theme it was attached to. Whenever I read a review of it and they review to hip, cool Boston kids, I don't understand what that means. I don't see that in the strip! [laughs] It's like, "What are they talking about?"

SPURGEON: What do you seen in there, then? This isn't you exercising your creative id, there are a number of impulses on hand, some of which are distancing. You do this satirical material about a future version of yourself. There are recurring characters -- like Abby -- and you get used to seeing people over again as you're reading it. Certainly your visual sensibility all by itself is a binding element. There's "Vegan Dad." There's the process of making art that comes up as a theme, and then there's the parody of that. So if it's not focused on young, hip people, how would you conceive of it now that it's under a couple of covers.

SPURGEON: What do you seen in there, then? This isn't you exercising your creative id, there are a number of impulses on hand, some of which are distancing. You do this satirical material about a future version of yourself. There are recurring characters -- like Abby -- and you get used to seeing people over again as you're reading it. Certainly your visual sensibility all by itself is a binding element. There's "Vegan Dad." There's the process of making art that comes up as a theme, and then there's the parody of that. So if it's not focused on young, hip people, how would you conceive of it now that it's under a couple of covers.

STEVENS: I don't know. That's the question I was wrestling with. I don't know how to describe it. Going back to working on it, it was me trying to make my deadline. So it was week to week, whatever I thought was funny. I would ask myself every week, "What do I feel like drawing this week?" And then it would kind of spring from that. I wish I had more... Matt Bors has politics, I would like this thing I could rely on. With

Failure I feel like I was figuring that out. I had "

Pope Cat," and the future strips, and coming back to the realism of earlier strips and

The Lodger. I was trying to mix it all, but I wasn't satisfied with any one thing. I couldn't settle on doing one thing week after week.

SPURGEON: Earlier this year I watched you read some of this work. It made me appreciate it in a different way. It was lighter. There's a humor that comes out in your voice regarding the characters in the strip, a slight mocking of what's going on with them. You have some distance from it -- you have a clear view on what's funny on its own terms and what's funny because by any rational standard it's outsized, ridiculous behavior. There's no endorsement of the absurdities that you're covering.

SPURGEON: Earlier this year I watched you read some of this work. It made me appreciate it in a different way. It was lighter. There's a humor that comes out in your voice regarding the characters in the strip, a slight mocking of what's going on with them. You have some distance from it -- you have a clear view on what's funny on its own terms and what's funny because by any rational standard it's outsized, ridiculous behavior. There's no endorsement of the absurdities that you're covering.

STEVENS: It's very lighthearted.

SPURGEON: I would imagine you sort of have to maintain a sense of humor drawing your own face, your own problems, over and over again.

STEVENS: Absolutely.

SPURGEON: I think people might feel the work is hopelessly self-absorbed if they look at it from the outside in and don't get in there and engage with the work strip to strip.

STEVENS: Why do I get stuck with that? How do I get that and

Gabrielle Bell avoids that, for the most part?

SPURGEON: I don't know. What do you think, Karl? Are we just being mean to you? Are we just being dicks for labeling you that way? I can't speak for other readers or people that write about comics, but I will admit that it took me a long time to come around on there being a lighter hand involved in your work, or at least a lighter touch than I would have guessed from my initial impression.

STEVENS: You thought I was taking myself too seriously.

SPURGEON: I'm not sure I thought exactly

that, but that's a rough version of it, sure. It seemed to me there was a self-satisfaction that you exuded in depicting your life. It took me a long time to come around to the humor as easily as I see it now.

STEVENS: But what was it about the content that made me seem like that to you?

SPURGEON: I don't know... maybe it's a hang-up about the kind of art involved? I'm not real sure.

STEVENS: It's something I think about. What is it about the art that puts some people off?

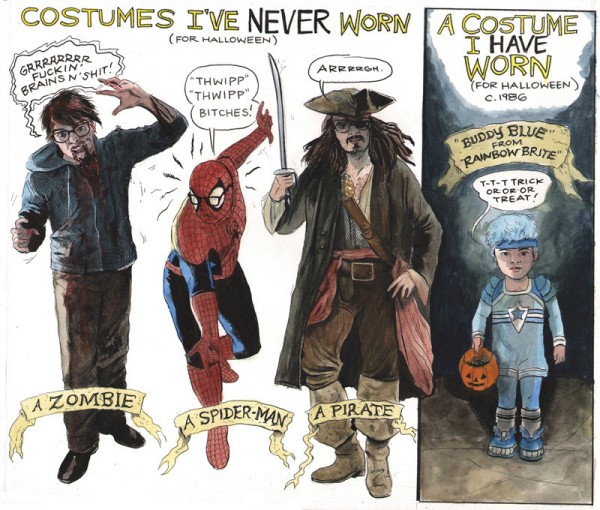

SPURGEON: I don't know -- or at least just behind the kinds of expectations we have for certain kinds of style, I couldn't tell you. It's a really fine line, right? Like with the Halloween strip in

SPURGEON: I don't know -- or at least just behind the kinds of expectations we have for certain kinds of style, I couldn't tell you. It's a really fine line, right? Like with the Halloween strip in Failure

, where you depict yourself as a kid, there are ways to take that where the ridiculousness of it is front and center, but there's a way to take it in where it's just you front-and-center, you being Karl Stevens, or a way to take it that favors the that it's you over anything you might be saying through this self-depiction. But I'm not sure why this would result in more people interpreting it one way over the other.

STEVENS: I'm curious about that. That's the very nature of autobiographical cartooning. How is what I do different in that way from [cartoonist

Robert] Crumb? Is it the art style? Is it because I wear glasses?

SPURGEON: [laughs] I think you'd have to be a pretty dim reader to -- I think in one point in one of the cartoons you even say "It's not easy being Karl Stevens." You'd have to be sort of a dimbulb to look at a strip like that and not see a distancing there, and a humor present. Hm. Why aren't we more generous with your work, Karl? I don't know. Maybe it's just me.

STEVENS: I think back to when I started, to want to become a cartoonist. When I was a teenager I read all these

Fantagraphics books and

Drawn and Quarterly books, Peter Bagge and

Julie Doucet, and being really inspired by these cartoonists. I wanted to be in that world. I went to conventions and sold mini-comics, and ingratiated myself. I submitted the comics I was working on then to those publishers and was rejected for so many years. I don't know. And where I'm at now, just building up whatever career I have, I guess, it still feels like I'm striving for the approval of a Fantagraphics or a Drawn and Quarterly. I don't know. I still feel like an outsider figure. I feel like all of my peers have passed me by. I'm like, "What is it?" [laughs] "What is it about my work?"

And there are real-world accolades.

The Lodger being nominated for the LA Times thing... I don't know.

SPURGEON: With work that appears like yours has... I assume since it was in

SPURGEON: With work that appears like yours has... I assume since it was in The Phoenix

it had a Boston audience and because it was comics that it had a comics audience that didn't all the way overlap with the Boston audience. And sometimes when you have a natural split in your reading audience, those audiences will read your work completely differently. So let me ask you this: was the Boston audience a good audience for your work? Did you feel like they took the work on the terms you'd prefer people take it?

STEVENS: It was a popular strip. I got letters and stuff. But that's another thing: I don't feel like it was necessarily reflective of Boston.

SPURGEON: I'm not so interested in Boston specifically but that Failure

was appearing somewhere in front of an audience that would have no way of bringing comics-culture signposts to their understanding of it.

STEVENS: They weren't. And it was very popular. I would hear from

Tony Davis at Million Year Picnic that people would come into the store that had never been to a comic book store before and want to find one of the books. There was stuff like that. But it's definitely a weird hang-up that I have. Why does the snobby comics community [laughs] ignore me?

SPURGEON: This is the third time we've talked, Karl. I think. I haven't totally

ignored you. [Stevens laughs]

STEVENS: I'm venting.

SPURGEON: I do think there's a way you're processed differently than cartoonists doing similar work, a way that's maybe not generous to the humor involved. I don't think that's an unfair observation. I wish I had a better answer for you why people don't appreciate your strip for all of its qualities as opposed to settling in on one or two. Of course, once you start to dissect things on that level, you're talking about these very refined reactions from a limited pool, you're wanting a couple of dozen people to see work a highly specific way. And then you might even be getting to a place where it's just a series of differences of opinion in terms of what people see in the work, and what they might value about it. It's hard to project a systematic reaction onto what people are saying because it's actually so few people that engage work in that way at all.

I don't know. It's all messed up. We should all go back to bed. [laughter] "Please re-try Karl's work, everybody."

The inarticulate nature of our conversation -- at least from my end -- is a sign of how specific and delicate these kinds of cultural conversations can be. But I've definitely feel you've benefited from having an audience that isn't familiar with Gabrielle Bell or Robert Crumb.

STEVENS: I'm working on this book for

Candlewick Press -- it's an illustration project. It's a drama about a woman that's a war vet as she tries to reinsert herself into her small town in New Hampshire. I just finished sketching it all out. It's been this great process for me, to work on a longer story -- which is something I've been jones-ing for this last few years -- and to work within a professional structure. They gave me an advance so I can actually live off of comics for another year.

SPURGEON: That's come up a couple of times in recent interviews I've done, Karl, the positives of the traditional book-publishing set-up in terms of there being an editor whose job it is to work with you towards making the book in question better, and that there's a process for completing the work that doesn't automatically exhaust you.

STEVENS: It's nice having some editorial input after working at

The Phoenix, where they were like "Get this in by Tuesday night."

SPURGEON: [laughs] Are you a different cartoonist now for this last run of work for

SPURGEON: [laughs] Are you a different cartoonist now for this last run of work for The Phoenix

, the material that appears in Failure

? And if so, how so? Where are you that's different?

STEVENS: I feel much more confident in my work. [pause] I guess. [laughter]

It's strange, because this new book, the book I'm working on, I didn't write it. It's my first experience translating a script. I did collaborate on the strip

Success, which ran for a year in

The Phoenix. But that was much more friendly. So I'm gaining discipline from this. I'm thinking about structure more. I'm also a different draftsman now. I've loosened up quite a bit in the last couple of years. I don't feel the need to crosshatch everything to death, and I'll try different techniques.

SPURGEON: There is an element to your art in Failure

that feels more lively than maybe some of the earlier books. You're not overworking the art, or even pressing your jokes -- at least not in most cases. There's more of a fuck-it attitude in terms of the humor landing that I thought might be a sign of increased confidence. The other option is that it comes from deep fear and that you did it from a stone panic. [laughter] But my first guess is that you just feel more like you know what you're doing.

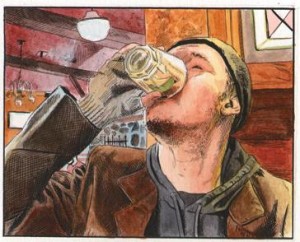

STEVENS: After sobering up, too. Almost every one of those strips was done the day before deadline, and incredibly hung over. [laughs] I wasn't able to really concentrate, and sometimes I had like no joke. The classic cliché of the cartoonist before deadline.

SPURGEON: There's a specific tradition of that in alt-weeklies, the kind of terrified, last-minute production as lifestyle.

SPURGEON: There's a specific tradition of that in alt-weeklies, the kind of terrified, last-minute production as lifestyle.

STEVENS: Oh, yeah. Yeah, yeah, yeah. I mean, I still drink. But now I take days off. [laughter]

SPURGEON: Your point is the overall production schedule is less... furtive.

STEVENS: It's definitely more under control. I know I'm like an alcoholic. It's just one of those things I have to deal with. Maybe I'll have to quit someday. [laughs] It's been okay. I just moved into this new place in downtown Boston with my girlfriend and she's on par with me as far as drinking goes. We definitely keep each other in check during the week.

This is boring personal stuff.

SPURGEON: This is the compelling stuff. [Stevens laughs] I'm going to run all of this in bold, with a slightly bigger font.

STEVENS: I definitely think about that, keeping the drinking under control. I wonder if I were more sober if I might have produced better work. Whatever. I definitely thrive on structure -- which is an alcoholic kind of trait. I'll spend eight to ten hours a day working really hard on comics or on painting and then at night get blotto.

SPURGEON: Assuming those factors fall into place, how much comics would you ideally want to do? You have opportunities in painting -- you just mentioned the painting. You said you would have done the

SPURGEON: Assuming those factors fall into place, how much comics would you ideally want to do? You have opportunities in painting -- you just mentioned the painting. You said you would have done the Failure

strip for as long as they would have had you, and that was a vocational proclamation, but still. At the same time, you said you want to do longer work. Is there a perfect career path for you? I know it's odd for some people to even think of this stuff as a career, but you're in your mid-30s now, you must have thought about it once or twice that way.

STEVENS: Oh, yeah. Oh my God, yeah. I'm 34.

SPURGEON: So you're 34. New apartment with the girlfriend. Not drinking as much. So what's ideal? How big a role does comics play in your ideal vocational outcome?

STEVENS: It remains the main muse. I can't see myself ever not doing comics. I've always had it in my head, this desire to have a new book every couple of years. I'm really kind of working all of the angles. I'm excited by this Candlewick book, I'm excited by the Kickstarter book I started that got moved to the back of things because the Candlewick book came up and couldn't say no. I'm hoping to sell that next if not to Candlewick than to another publisher. Just keep putting out books. Having Marc there, knowing that I would put out just about everything I would do, it's nice having that security. I can never shake comics. I came to them at such a young age. I look at

Bernie Krigstein, who freed himself of them. I read that

Art Spiegelman story about him talking about his panting in terms of those being his panels now. I just hope that doesn't happen to me. [laughter] I hope I never say "Fuck it. I'm just going to paint." I don't think I could, you know? The hook is in too deep.

SPURGEON: Do you have a longer form comic in mind, after this current gig? Is that the Kickstarter project you mention?

STEVENS: It's called

Imitating Life. It's a comedy, a love-triangle story. And there's a zombie story that I have, too. But I might wait on that.

SPURGEON: You draw a good-looking zombie, Karl.

STEVENS: I've been doing some superhero stuff, too. I would love to get my feet into that. I thought it might be fun to do mainstream work.

SPURGEON: You have a whole Tumblr devoted to that. [Editor's note: It has since this summer become a more general tumblr.] Have people responded to your superhero drawings?

STEVENS: Yeah, just not in the way I hoped. [Spurgeon laughs] I was hoping that some editor would see that and say, "Hey, do you want to do the cover to

Punisher?" And I would be, "Yes. Yes, I do." Maybe not

Punisher.

Swamp Thing, that's the book I want to do. I was looking at the

Steve Bissette/

John Totleben stuff for inspiration. I thought, "That might be a fun book to work on." That might be fun. And there's money, too.

It's the old saw of being a freelancer/grifter. You're just trying not to get a job. I talk to [the writer and cartoonist]

Tim Kreider about this a lot. Our one goal in life is to not have to get a job. [laughter] How long can we keep this going?

*****

*

Failure, Karl Stevens, Alternative Comics, softcover, 1934460028, 160 pages, 2013, $21.95.

*****

* cover to

Failure

* photo of Stevens from 2012

* various images from this latest

Failure book, hopefully understandable by choice due to proximity to some sort of passage that explains the context

* the Swamp Thing image I don't think is from the

Failure book and instead appeared on the cartoonist's Tumblr

* a drawing from Stevens I found on-line (below)

*****

*****

*****

posted 12:00 am PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives