June 21, 2009

CR Sunday Interview: Kevin Cannon

CR Sunday Interview: Kevin Cannon

*****

I first became aware of

Kevin Cannon when he showed up in initial publicity as a member of the

Big Time Attic studio alongside

Shad Petosky and

Zander Cannon. He first caught my attention as a solo artist when I found a collection of his

Johnny Cavalier strips and began to track

his contributions to 24 Hour Comics Day.

This series of exercises eventually led Cannon to attempt a graphic novel through a series of monthly 24-Hour Comic experiments -- the 288-Hour Comic. This almost worked in terms of his following the rules, and it more than worked in terms of the results.

That comic became Far Arden, collected this month by Top Shelf Comics into

a hardcover edition.

Far Arden is an arctic sea adventure where every single person involved seems to have the emotional make-up of a tipsy, spiritually fragile graduate student. Since this also describes most of the people in my circle of friends, I found

Far Arden affecting as well as being impressive for its lunatic narrative flow and the unbelievably well-crafted, overall look to the thing. Cannon has also contributed to several of the splashier Big Time Attic projects and has done a number of notable, super-sized illustrations for the Minneapolis area alt-weeklies. I might be convinced by the right malevolent spirit to trade my past for his future, and I like my past. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: As I understand it, you didn't think about doing comics until the opportunity to do some came your way in college. Is that true? Do you think the process was different for you in making your first comics than for someone who maybe always wanted to do them? Have you since developed an interest in the art form and other practitioners of same beyond making your own TMNT comics once upon a time? Did you connect back to that early exposure? Do you think your aesthetic is different than other cartoonists as a result?

KEVIN CANNON: I grew up reading newspaper strips and for a long time I thought that's the career path I wanted to take. But as soon as I started researching what that would take -- i.e. the long-shot odds of getting published, the lengthy contracts, the stultifying editorial oversight -- I lost the drive. I continued reading the dailies every morning, because they were there on the kitchen table, but after age 15 or 16 I no longer thought that being a cartoonist was in the cards. My heroes then were

Kafka and

Kerouac, so through most of high school I thought I would be a novelist. [laughs] I even wrote a novel back then -- imagine a very sappy, poorly written

The Road. I punched that thing out a few pages a night for about a year, so I guess that experience was a precursor to

Far Arden, although I haven't made that connection until just now.

My exposure to comic books and graphic novels seems bizarre when I look back on it. I consumed every bit of

TMNT I could get my hands on, but for some reason

never felt the need to pick up other mainstream titles. I read a lot of

MAD, and my grandma had a stack of old '50s romance comics that I leafed through on holidays, but that was it. I think I'm drawn to unique art styles, the way you you look for music that has a unique sound. Maybe that's what kept me away from mainstream comics for so long. As an outsider looking at superhero comics -- and manga, too -- it looks like all the artists are desperately trying to draw exactly the same style. I don't understand that way of thinking.

Anyway, so in college I started drawing a weekly strip called

Johnny Cavalier for the school paper -- I had gone in to the office looking for a job as an illustrator, but they said they needed a cartoonist, so that's how that started. It wasn't until midway through my college career after I discovered

Hate and

Eightball that I realized that this is where I was taking

Johnny Cavalier and that this is what I wanted to do professionally. However, I'm glad I had a grounding in the dailies, because I think that gave me a good sense of timing, and how to deliver a solid punchline.

SPURGEON: A theme that seems to dominate your young career is how much you've benefited from tight feedback loops. I believe you're a private school kid, your Grinnell work would have been mostly read by people in your same general circumstance, and now you have a tight core of fans and fellow artists that follow what you do now. Is there something that appeals to you about this kind of attention as opposed to the more diffuse kind that you'd have if you'd signed a contract with United Media right out of school and were doing Johnny Cavalier in 200 papers and getting back six e-mails a year? Has feedback been generally important to you as a way to develop?

SPURGEON: A theme that seems to dominate your young career is how much you've benefited from tight feedback loops. I believe you're a private school kid, your Grinnell work would have been mostly read by people in your same general circumstance, and now you have a tight core of fans and fellow artists that follow what you do now. Is there something that appeals to you about this kind of attention as opposed to the more diffuse kind that you'd have if you'd signed a contract with United Media right out of school and were doing Johnny Cavalier in 200 papers and getting back six e-mails a year? Has feedback been generally important to you as a way to develop?

CANNON: Yeah, that's so true, I've always had really small, tight feedback loops. On any day of the week I'd rather have honest, harsh criticism from a few people whose opinions I care about than get a hundred gushing emails from complete strangers. In college I had a group of friends who read my weekly strips and would give me feedback. A lot of times it was harsh, maybe overly critical, but I matured a lot based on their reactions. Plus, when they laughed at a joke you know they meant it, and that was incredibly satisfying.

I'm in a similar situation here at Big Time Attic. Zander gives me incredible feedback on anything I put in front of him, and this guy is one of the best comic book writers in the business.

SPURGEON: How do you feel about the Johnny Cavalier

work right now? I know that for a lot of college cartoonists that can be a very intense experience because it's part of a lot of a specific period in folks' lives. What do you recall when you think of that work now?

CANNON: Some of the art is a little embarrassing to look at, but that's a pretty superficial reaction. Mostly I'm excited by how the book has touched young cartoonists.

Carl Nelson (

Outwise),

Tim Sievert (

That Salty Air), and

Julia Vickerman (

Yo Gabba Gabba) have all told me that the collected

Johnny Cavalier strips meant a lot, or influenced them in some way. And these weren't Grinnell students, so I'm not really sure how they picked up copies of the book.

Mostly, looking at old

Johnny Cavaliers makes me realize what a great learning experience they were. Zander and I talk about this a lot, that we think doing a strip for a newspaper should be required for anyone considering a career in comics. You're forced to learn about scanning, layout, reduction, etc., but the most important lesson is how to hit a deadline. We've met a lot of art school students who have no idea what a real deadline is because their professors never enforce them. These students will turn in pencils and say, "Oh, I didn't have time to do inks, but here's what I've got," and the professor is like, "Okay, that's fine, great job." Obviously, that's a gross generalization, but based on real anecdotes! With a newspaper strip, you either get the finished product in on time or you don't. There's no pat on the ass for a job half done.

SPURGEON: What were your other college strips like?

SPURGEON: What were your other college strips like?

CANNON: There was a political cartoon called

Third Party, a gag panel cartoon called

Heaters, an acerbic three-panel strip called

Art Guy, and a dada cartoon called

absent. Most of these ran for one semester each, alongside

Johnny Cavalier. But

Cavalier was the anchor, and ran for all four years.

SPURGEON: The one thing I find interesting about your not being Zander Cannon's brother is that this was the basis for your contacting him, which means there was enough institutional memory at Grinnell that people would bring up Zander. Am I getting that right? Can you talk in more explicit terms how that relationship developed?

CANNON: When I was a freshman I ran into a guy named Xander (the first in many bizarre coincidences). Xander had graduated the year before, but was on campus working in the art building. He was a freshman when Zander Cannon was a senior, and it was Xander who concluded that I must be Zander's brother. I immediately read all of Zander's old strips in the school's microfilm archive, and concluded that Zander was some kind of god. So I nervously introduced myself via email. He responded, but I let the conversation die. That was freshman year.

Jump ahead to junior year and I needed a job over the summer. My mom, in her infinite wisdom, convinced me to write a letter to Zander asking if he ever had interns. So I wrote the letter, and Zander agreed. I ended up spending four hours a day in his little Minneapolis studio, helping out on Alan Moore's

Smax, which Zander was just starting to illustrate. In all honesty, we didn't get a lot done. Zander was getting ready for his wedding that August, and we were constantly (and fortunately) distracted by all the other cartoonists in that building.

Sam Hiti,

Adam Wirtzfeld, and Shad Petosky worked one door over, and

King Mini shared Zander's space. Seeing all of their art in progress and hearing their thoughts on process and the comics industry was pretty priceless.

SPURGEON: You used to do really detailed pencil portraiture, which is interesting to me in that it seems an enterprise completely divorced from the kind of symbolism and simplification I think of when I think of communicating in comics form. Does that kind of art -- or even your painting, you studied painting -- influence your cartooning in a way that might not be apparent to someone taking that work at face value?

SPURGEON: You used to do really detailed pencil portraiture, which is interesting to me in that it seems an enterprise completely divorced from the kind of symbolism and simplification I think of when I think of communicating in comics form. Does that kind of art -- or even your painting, you studied painting -- influence your cartooning in a way that might not be apparent to someone taking that work at face value?

CANNON: The portraiture thing happened because at that time (high school years) I believed in objective value in art, specifically that the more realistic something looks, the better it is, and the more praise should be heaped upon the artist. My neighbors saw that I was doing realistic pencil drawings for school, and were more than willing to part with a few hundred bucks for me to draw pictures of their kids. It was hard to say no to that, and for a long time I enjoyed it. But college killed my "representational art = good art" ideal, specifically via two art classes. The first class surveyed three hundred or so years of American art from the hyper-realistic stuff back in the day to post-modernism and beyond. I cheered for representationalism at the beginning of the class, but that part of me was slowly beaten down -- not by force (the class had no agenda, per se), but by being exposed to modern art, piece by piece.

Senior year I was in a seminar on German Expressionism, and those pieces, especially the woodcuts, blew me away with their wild figures. Most of these artists were basically non-sequential cartoonists. The life and energy and complete not-giving-a-shit about realistic human proportions are the foundation of all my comics work today. If I'm the product of my influences, it's Pete Bagge meets

Lyonel Fieninger, or

R. Crumb meets

Ernst Kirchner. At least, that's what I'm striving for!

SPURGEON: I apologize for not knowing this stuff, and I think it might be more fun for me to just ask rather than try to nail down the information before doing so. You and Zander and Shad Petosky created Big Time Attic earlier this decade. I was wondering if you could talk about that experience in broader terms, because it's the kind of business enterprise a lot of folks consider doing. First of all, is it still around? I always get a little bit confused with you guys. What's its status? How has it developed in ways that were maybe different than your original conception? You were such a young artist that it seemed to me odd that you would join this kind of group because your ambitions might settle anywhere -- has that been a good structure for you in terms of development?

SPURGEON: I apologize for not knowing this stuff, and I think it might be more fun for me to just ask rather than try to nail down the information before doing so. You and Zander and Shad Petosky created Big Time Attic earlier this decade. I was wondering if you could talk about that experience in broader terms, because it's the kind of business enterprise a lot of folks consider doing. First of all, is it still around? I always get a little bit confused with you guys. What's its status? How has it developed in ways that were maybe different than your original conception? You were such a young artist that it seemed to me odd that you would join this kind of group because your ambitions might settle anywhere -- has that been a good structure for you in terms of development?

CANNON: Big Time Attic still exists, but it has molted several times. Let me lay down the history, as I remember it. So back in the summer of 2001 I was Zander's intern, and Shad worked next door, so we hung out a lot. After that summer Zander moved to Japan, Shad became a freelance web developer and Flash guru, and I finished school and tried to keep doing portraiture. Jump to summer '04: Zander was moving back to Minneapolis from Japan and he and Shad and I were looking to join forces, because we thought that if we pooled our resources and diverse talents, that we could be more successful than we were as three lone freelancers. Actually, there were seven or eight cartoonists and artists talking about forming a group, but Shad, Zander and I were the only ones who gelled. I was incredibly young and naive, but that turned out to be great for me because I learned from Shad and Zander's experience. And what they got from me was a workhorse, someone who would stay late and make sure the jobs got done.

Our dream -- my dream -- was for Big Time Attic to be a comic book studio, to try and put out a book a year and eventually make a living off royalties. Shad, I think, wanted something bigger from the beginning, and that created a little tension. I mean, Shad had always envisioned having employees, and that was a big shocker to me and Zander. It was like a weird three-way marriage or something. Shad was the visionary, and Zander and I were the conservative voices of reason. So as far as I see it, that balance meant that we grew, but not too wildly. Thanks to Shad's connections in the new media realm, we started getting animation jobs for Target and Cartoon Network, and at one point we had maybe a dozen employees. Eventually Big Time Attic was a lopsided company with no unified direction: on one side, Zander and me drawing comics, and on the other side, Shad and the animation department doing animation and new media stuff.

So in 2007 Big Time Attic split into two separate companies: the animation department became

Puny Entertainment, and Big Time Attic shrank back down to me and Zander doing comics. We separated, but it wasn't a divorce -- it was more like a cell splitting in two. Puny -- headed up by Shad and King Mini -- is now wildly successful. They're doing most of the animation for Nickelodeon's

Yo Gabba Gabba. And Zander and I are finally reaching our "one graphic novel a year" output goal, with publishers like

Hill & Wang and

Simon & Schuster, so we're pretty happy.

Whew. And that's not even the long version of the story, but hopefully that clears up what Big Time Attic is. If someone came up to me on the street and said, "My friends and I want to start a studio like BTA, should we do it?" I'm not sure what my answer would be. It was great for me, as a young artist with no experience. But it was only great because Zander and Shad knew what the hell they were doing, and already had a solid client list. And even then, we barely made it. I'm still paying off credit cards from the first few years of BTA. So I guess my answer would be yes, do it, but be flexible, be long-sighted, and get ready to be poor.

SPURGEON: I was wondering if you could talk about some of the non-glamorous jobs you've done since joining up with those guys, say some of the background drawing you've done, or maybe some of the teamwork projects... has any of that work been particularly instructive, or is it just applying the lessons of craft, a kind of day job?

CANNON: When we started Big Time Attic, we took every single job that came our way. It was nuts. Even if we had absolutely no idea how to do a job, we'd take it. That included designing a pizza restaurant, character animation, professional photography touch-ups, digital illustration, book design... it goes on. But every time we got a job, we researched the hell out of how to do it, hired people to help if needed, and got the job done.

Our classic example of jumping in headfirst was when we took on a job to design a family fun center called "

Action City." The contractors for the park wanted to hire us because we, as cartoonists, would give the place a fun, original feel. These contractors had spent years driving around the country and researching similar parks, and knew that they wanted theirs to stand out from the pre-made murals and generic designs that you can buy off the shelf. So we were in on this project from the blueprint stage, designing everything from themed birthday rooms to a 30-foot fiberglass back-lit volcano climbing wall. Shad and I even lived on site for three weeks before the opening. I got up at 5am every morning to guide construction crews and muralists, and Shad was on site late every night working on identity, marketing, the computer systems, etc. etc.

I was burnt out after that, but mostly I missed drawing comics, so as soon I got home I drew a story called "Our Endangered Cartoonists" just to help me come down from the nervous high I'd been on for three weeks in Action City.

SPURGEON: What was the extent of your contribution on the GT Labs book Bone Sharps, Cowboys and Thunder Lizards? That was a fascinating book in many ways that I thought never quite coalesced as sharply as some of Jim's other works. How you do feel about that book?

CANNON: Yeah, the reaction to

Bone Sharps has been less positive than we'd hoped. Part of that may be that Jim tried something new, weaving more narrative among the facts than in his previous books. So in that sense maybe it was riskier. I love it, but obviously I'm a bit biased! My role on that book was lettering and backgrounds, and I also did some of the layouts and acted as project manager.

SPURGEON: You've spoken in positive fashion about Jim Ottaviani and GT Labs. What is it that you think is admirable about Jim's enterprise, his approach to comics? What appeals to you about what he does?

SPURGEON: You've spoken in positive fashion about Jim Ottaviani and GT Labs. What is it that you think is admirable about Jim's enterprise, his approach to comics? What appeals to you about what he does?

CANNON: During the first few years after college I remember feeling like I was "getting dumber." My brain was atrophying. For most of our young adult lives, we're forced to read the greatest books in the Western canon, forced to write papers that sharpen our critical thinking and communication skills, and forced to listen to and talk to people with interesting, divergent viewpoints. And then -- boom -- you're 22 and you get your diploma and you're on your own in regards to what you feed your mind. I didn't feed mine very well, and I felt emptier and emptier because of it, although I couldn't pin down the cause at the time.

Then Jim Ottaviani comes along with the script for

Bone Sharps, and all of a sudden I'm at the library again, digging up books on paleontology and dinosaurs. I'm being a little over-dramatic, but having an excuse to

learn again was really exciting. The same thing happened a few days ago, walking to the library to pick up some books on evolution for a graphic novel Zander and I are doing with Jay Hosler. And it's not as though I can't read weighty books in my free time, but it's great to be able to marry those books with comics ... and get paid for it, to boot.

So getting back to Jim, he's got the best business model: he finds something he likes --

Niels Bohr, paleontology, the moon race -- and makes a graphic novel out of it. And Jim has a day job, so there's no temptation to muck with the integrity of the work just to make it sell better. If that were the case,

Bone Sharps would've had a lot more babes in it.

SPURGEON: You're going to do this a bunch of times as the book's out, but can you describe in specific terms how

SPURGEON: You're going to do this a bunch of times as the book's out, but can you describe in specific terms how Far Arden

went from that initial 24-Hour comic to this multiple 24-Hour comic graphic novel. Because that just seems insane to me. Were the stunt aspects -- the time limit, for instance -- rigidly adhered to?

CANNON: The whole thing started as a dare from my friend

Steve Stwalley. We and most of the members of the Minneapolis Cartoonist Conspiracy have been doing 24 Hour Comics Day since 2004. Shanks actually made his comics debut during the 2005 event, in a story called "Exit Strategy," and that story wound up in Nat Gertler's "24 Hour Comics Day Highlights 2005" anthology. Anyway, after the 2006 event was over, Steve dared me to do one 24-hour marathon a month for a whole year, with each month's output being a chapter in a 288-page graphic novel.

The first four chapters of

Far Arden were legitimate 24-hour marathons, minus being surrounded by people. It was pretty lonely. After the fourth event my body felt ragged and my sleep schedule was messed up and was impacting my day job, so I gave up the marathons in favor of smaller, shorter spurts. So each page was still taking about an hour, and until the very end I was still producing a chapter a month. Now I think I can only handle one 24-hour event a year.

After chapter seven was finished I bundled up those chapters and mailed them to Chris Staros at Top Shelf. Tim Sievert was working on

That Salty Air in a little corner of the Big Time Attic studio and I guess that made me eager for my own Top Shelf book. Chris called me up a little while later to tell me that he was passing on

Far Arden, but we had a really good chat and I don't have a ton of experience with unsolicited manuscripts, but I don't imagine that a lot of publishers would have called like that. He gave me really good notes about what wasn't working for him, and I think those notes were always in the back of my head as I wrote the final eight chapters. About a year later, not wanting to give up on Top Shelf, I sent the finished

Far Arden to both Chris and Brett [Warnock], and to my surprise they picked it up.

SPURGEON: Was it hard for you at all to find a level at which you could create in such a short time span with as much detail as you bring to the project? Because there were moments in which you drew an entire boat or otherwise provided a more elaborate illustration where I and likely many others felt the same impulse that led Marge Simpson to yell at Homer during the trucker episode, "Don't fill up on bread!" Did you adjust your approach at any point during the initial project or project entire?

SPURGEON: Was it hard for you at all to find a level at which you could create in such a short time span with as much detail as you bring to the project? Because there were moments in which you drew an entire boat or otherwise provided a more elaborate illustration where I and likely many others felt the same impulse that led Marge Simpson to yell at Homer during the trucker episode, "Don't fill up on bread!" Did you adjust your approach at any point during the initial project or project entire?

CANNON: But bread is great! The trick is to do an easy page in 40 minutes, so you have 80 minutes to do your big detailed splash page. Actually, it's even more complicated than that, because you've got to factor in restroom breaks, eating, quick jogs, socializing... so each page

really takes 40-50 minutes, not 60. But yeah, it took a few years to develop a style that I knew I could pull off in an hour and still look decent. If you compare a page from

Far Arden to a page from "Exit Strategy," you can easily see the rough beginnings. It's not that there are fewer lines on the page in

Far Arden, it's that the lines are more confident because I knew how much I could get away with.

SPURGEON: When did it begin to coalesce for you in terms of a project that you thought might work as one massive comic book? Was that different than a project you might work on all the time for a shorter period of time, or is that sense of something coming together the same?

CANNON: I knew the scope from the get-go. Shanks' last line in Chapter 1 is me basically telling my future self what I need to try and establish and ultimately wrap up over the next eleven chapters. Usually when I write a comic I'll get a germ of an idea, and that snowball will either melt immediately or turn into an avalanche. There's not a lot of middle ground. If it's an avalanche idea I'll have to sit down and write a full script immediately. With a short comic, like my

Chapter 99 one-pagers, it's easy to get the spark and then sit down and produce a finished comic in the same day. But it's obviously tougher with longer projects. I have notebooks full of plot points and character sketches for various graphic novels that are hard to execute because I usually only have a free hour or two a day, and it's difficult to find your bearings when there are tons of notes to sift through. So the chapter-a-month marathon style of

Far Arden was nice because it gave me a framework in which to organize my thoughts. Plus it was maybe a little like writing for television in that once a chapter was done and "aired" there was no going back to fix things. With my longer projects there's a tendency to change a thing at the end of the script, and then need to sift through all the earlier notes to set up that change better. I suppose everyone goes through that.

SPURGEON: One of the fun flourishes is your use of elaborate sound-effects. If I had to hazard a guess, I would suppose that this a visual shorthand you latched onto, but were there other influences? Do you have a favorite from the ones you used?

SPURGEON: One of the fun flourishes is your use of elaborate sound-effects. If I had to hazard a guess, I would suppose that this a visual shorthand you latched onto, but were there other influences? Do you have a favorite from the ones you used?

CANNON: I'm sure they were inspired in some way by the old

Batman TV show. I like how the sound effects in that show are a little cheeky, a little ridiculous. They lighten the mood and hopefully break the fourth wall a little bit.

I also latched onto them because they're incredibly utilitarian. In

Far Arden, David's "THROW UP A LITTLE IN MOUTH" sound effect really cuts right to the core of what he's feeling and doing, and it only took one panel to accomplish. If I used a normal sound effect like "HRMPH" I suppose some people might deduce that David had thrown up a little in his mouth. But how do we know he hasn't thrown up a

lot in his mouth? Or what if he has merely belched, without any throw-up at all? One solution would be for the character to have the "HRMPH" sound effect, and then to tell another character, "I've just thrown up a little in my mouth." But given the fact that he's got to spit out the throw-up first before he can attempt to say anything, we're looking at three, four panels just for that one gag. That's just wasteful.

SPURGEON: You've spoken how

SPURGEON: You've spoken how Far Arden

kind of scratches an itch for you both in terms of its specific subject of arctic exploration and a more general sense of being in the outdoors that's stuck with you since you were a kid. Can you give an example of a specific story element that draws on that more personal sense? Were both of those things explicit influences, or were they things that you see now that the work is done? In general, is there anything in there that you're surprised reveals itself in the comic?

CANNON: I think my interest in the arctic can be traced back to a few separate childhood experiences. One is that I grew up in Minnesota, which meant long winters spent skiing and tracking animals in the woods behind my dad's house. So the memories of brutally cold winds and frozen boogers are fond ones. Also, I spent a lot of my summer vacations on a small island off the coast of Connecticut. The island was in a chain of maybe thirty other inhabited islands, and each island had their own character and bizarre histories (one involved the pirate Captain Kidd and another involved the circus performer Tom Thumb). So when I was in college and becoming really interested in polar history, I spent a lot of time looking at the strange islands of the Canadian High Arctic and imagining that each of them had their own bizarre personalities, too.

Another big influence was Jon Krakauer's book

Into the Wild which I read at age 16. I guess someone could make a case that Army Shanks is really Chris McCandless, had he survived and was living in an abandoned whaling station instead of an abandoned bus.

As far as a surprise reveal, I think that would be the character of Anger -- the half man, half beast. He was really just a throwaway character drawn into the first few pages. In fact, he was such a throwaway character that all we see of him initially is his big, shackled forearms. But he kept popping up later, probably because I identified with his vague "raised in the wild" history. His friendship with Alistair was a surprise, too. Alistair worships him, to the point where Alistair's brain chooses Anger as the one person he wants to walk into the unknown with. Without getting

too Psych 101, I think that maybe Anger represents the nature/urban dualism I experienced growing up, and Anger's flight to Vancouver to be a movie star -- and his ultimate demise -- mirrors how I've completely lost touch with nature as an adult.

SPURGEON: Given the comic's final outcome, I think it's also fair to say that there are critical elements in it, too: everything from a distrust of blindly following dreams of the kind one has in school to people being generally disappointing to a very specific conception of Eden myths. Were you aware of this critical vein in Far Arden

when you were doing it? Is there any element of it you'd be willing to unpack a bit and talk about what you were trying to do?

CANNON: I don't want the take-away message from

Far Arden to be "don't follow your dreams." We all have ridiculous dreams that we follow, and I'd be a hypocrite to criticize that. I think the criticism is aimed at the means we take to achieve those ends. The backstabbing and the trampling over one another really amount to nothing. And the rewards, if and when we receive them, can never live up to our expectations.

That being said, there was never any specific goal in my head to lay down a critical vein throughout the book. That just came out naturally. Maybe the one pre-meditated idea was that I wanted the indifferent and harsh personality of nature to shine through every aspect of these characters' lives. The few journals I've read from polar explorers often mention their awe of both Nature's extreme beauty and extreme cruelty. They paint a landscape of a place that giveth more and taketh away more than anywhere else on earth, and I wanted to try and capture a little bit of that in Shanks' world.

SPURGEON: The sheer brutality evident in your conclusion seems like a whole thing in and unto itself. Were you aware that's where you were going? How might you ask the reader to consider this super-severe, shattering outcome in light of what's gone before?

CANNON: Actually, the ending was the only thing I knew about from the beginning. All the other plotlines and characters -- except Shanks and Hafley -- were made up as I went. I suppose that, knowing the ultimate outcome, I built up readers' expectations along the way so that the ending would be that much more shocking -- a bit of emotional pornography, I guess. But in another sense, I actually don't think that the ending is that harsh, if you consider the truly wonderful things the characters go through leading up to that point.

You're right, though, the ending will probably bother anyone who's a sentimentalist. It's no Meg Ryan movie. Let's be clear, I wrote the book for me, and I'm a person who doesn't like a lot of magic or fantasy. I like things to confine to reality, at least reality as we know it or can imagine it.

SPURGEON: You seem to be fond of your main character, at least enough so you've considered doing other works with him. One thing a couple of people mentioned to me upon reading

SPURGEON: You seem to be fond of your main character, at least enough so you've considered doing other works with him. One thing a couple of people mentioned to me upon reading Far Arden

is that Armitage Shanks seemed a tiny bit slippery, that a sense of him was out of their grasp. What is it that appeals about him to you, do you think?

CANNON: Shanks is slippery because I haven't quite figured him out myself. Part of the fun of the book was creating Shanks' habits and back story as I went along.

I think what appeals to me about Shanks is that he's a sort of nightmarish extrapolation of myself -- someone who excelled during his school years but somehow got off track and ends up living alone in a whaling station looking at old Polaroids, reminiscing about the people he's hurt or given up on along the way. So in that sense,

Far Arden is a kind of autobiography of the future, a tale of how

not to spend the next 20 years of my life.

SPURGEON: Can you talk a bit about some of the insanely detailed single-image comics you've done for

SPURGEON: Can you talk a bit about some of the insanely detailed single-image comics you've done for City Pages

? I think there was more than one. I really liked the one I saw. That seems an entirely different enterprise. Is there something you looked at as a model? How hard is it to maintain an overall visual impression given the detail and even clarity between those details?

CANNON: You probably saw the "Rock Atlas" one, which is a big two page spread showing a lot of rock clubs around Minneapolis, but surrounded by lots of little details. I guess I like the map quality of it. I think I'd be a cartographer if I'd been born a hundred years ago.

The thing those

City Pages illustrations have over regular narrative comics is that you can enter at any point, stay as long as you like, and always find something new when you return. Those illustrations are just big Easter egg fields. I love Easter eggs. I try to throw in as many Easter eggs as possible, and that's especially true in

Far Arden -- if people are going to drop twenty bucks on a book I think they should be able to read it a few times and find something new each time.

SPURGEON: I'm terrible at that kind of thing -- can you give me one "Easter egg" example from

SPURGEON: I'm terrible at that kind of thing -- can you give me one "Easter egg" example from Far Arden

?

CANNON: Toward the end of the book, Fortuna tells Shanks that she's "going outside now and may be some time." These are the famous last words of

Captain Lawrence Oates, who sacrificed his life for the good of

the failed British South Pole expedition. Fortuna doesn't kill herself like Oates did, but I wanted to give astute polar buffs a sense of dread. There are also a couple of little neuroscience Easter eggs, but I'd rather wait and see if anyone out there is nerdy enough to find them. My cousin is a geneticist and she figured out the code at the end of chapter 3 right away!

SPURGEON: What do you have planned for the immediate and not-so-immediate future project-wise?

CANNON: T-Minus: The Race to the Moon is coming out soon -- that's Zander's and my second book with Jim Ottaviani. And we're about to start illustrating Jay Hosler's

Evolution: A Progress Report, which is the sequel to Mark Schultz's

The Stuff of Life. I've got a few short comics in anthologies, like Ed Moorman's

Ghost Comics and the upcoming nod to old-timey newspaper strips,

Big Funny. Other than that I'm trying to decide on what to do for a follow-up to

Far Arden, but nothing's solid yet.

*****

*

Far Arden, Kevin Cannon, Top Shelf, hardcover, MAR094430 (Diamond), 9781603090360 (ISBN13), 400 pages, May 2009, $19.95

*****

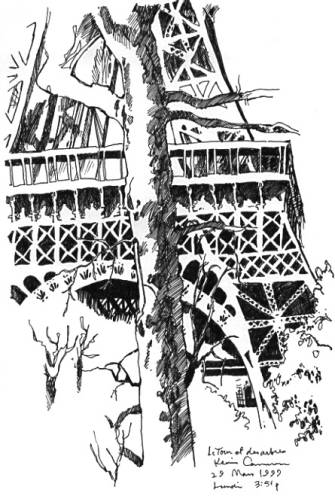

* cover to the new Top Shelf hardcover version of

Far Arden

* photo provided by Kevin Cannon

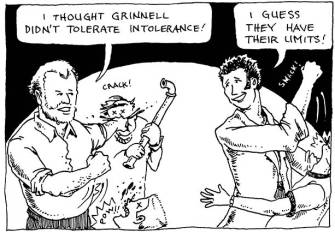

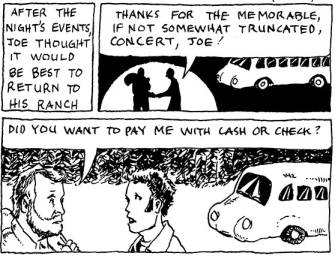

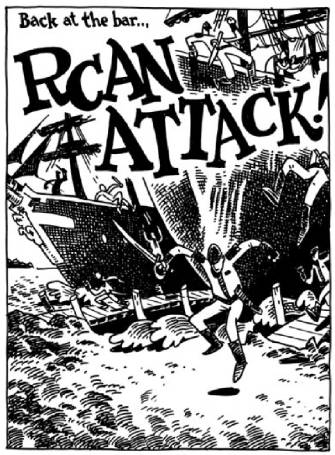

* three different pieces of art from the

Johnny Cavalier strip

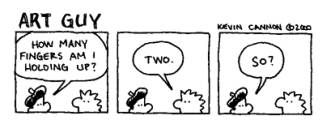

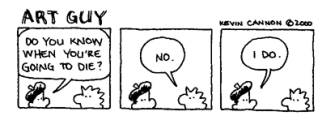

* three different pieces of art from

art guy

* from Kevin Cannon's sketchbook

* recent magazine strip

* photo from the Action City gig stolen from one of the BTA blogs

* from the

T-Minus gig for Jim Ottaviani

* section from Cannon's massive strip about the 24-Hour comic and what led to

Far Arden

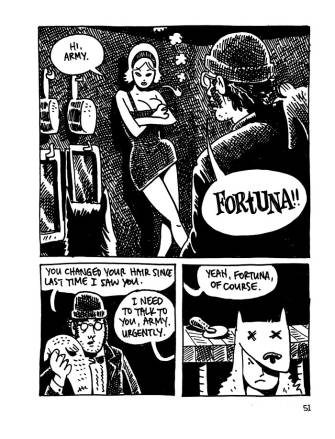

* one of the elaborately-done panels that made me worry for Cannon finishing the comic

* one of the sound-effect panels

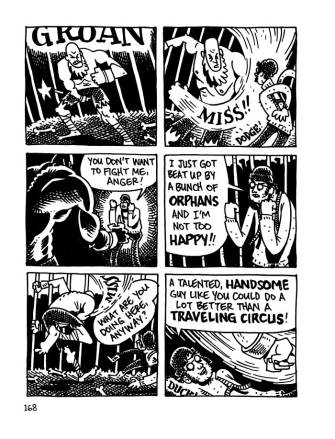

* more really elaborate drawing

* some of the loose action

* a section from one of Cannon's cartoon maps

* more

Far Arden

* a final, fun

Far Arden page (below)

*****

*****

*****

posted 8:00 am PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives