September 14, 2008

CR Sunday Interview: Scott McCloud

CR Sunday Interview: Scott McCloud

*****

I read the comics that make up the new collection

Zot!: The Complete Black and White Collection: 1987-1991 when I was a college student, much older than the 'tween and early teen that seems perfectly suited to the manga-influenced tale of Jenny Weaver and her superhero friend from another Earth. Instead, I was a terribly confused young man, who, like many others at that age, wanted to regress to my own 13-year-old days and those concerns and all the feelings rampant in those first, true, out-of-family friendships. I probably fell a little bit harder for the title than I should have, and when I talk below about fans that seem to like

Zot! more than creator Scott McCloud seems to, I'm to be counted among their number.

Given the major crush of news that came with McCloud's

recent making of a comic to introduce Google's Chrome browser, a Scott McCloud interview devoted to the new

Zot! book and general industry talk is a bit like an interview with Sarah Palin limited to the summer of 2008 in Alaskan politics. I hope you'll indulge me as much as Scott does in our conversation below.

Zot! remains interesting to me now that I'm no longer a young man and only a little bit confused because I think it may be one of best works out there in any medium when it comes to capturing the quality of lives lived by bored 1970/1980s suburban teens and exploring the way those kids turned to fantasy as a coping mechanism. It is also of great interest as an historical document within comics: McCloud's use of manga storytelling tropes, for example, feels prescient considering their present-day ubiquity; similarly, the medium now sports an entire library shelf of work aimed at a young audience in a way that makes McCloud's first series less of the total odd man out it once was when it comes to finding readers able to process all that it's trying to do.

I always enjoy talking to Scott, and I laughed several times during the interview below.

*****

TOM SPURGEON: You just got back from the East Coast, right? You did some appearances on behalf of the book.

SCOTT McCLOUD: Harper had me doing three events in New York and, of course, I'm always promoting at talks and whatnot around the country.

SPURGEON: Was being out for this book any different than being out for the kinds of books you've been doing more recently?

SPURGEON: Was being out for this book any different than being out for the kinds of books you've been doing more recently?

McCLOUD: [laughs] It was different than

Making Comics... I didn't have to do it for

an entire year! [laughter]

SPURGEON: Do people make that connection between the kind of work that you do now and the older work, or did you see people that have only kind of latched onto this work?

McCLOUD: It's very unpredictable. Most of my fans are pretty eclectic: they have a broad understanding of the many things I've done. But then you have these little pockets of people who only know me for

Zot! and are dimly aware that I've gone on to do some kind of book afterwards.

SPURGEON: [laughs] Right.

McCLOUD: And then there are others who are surprised that I had ever done any kind of fiction. Then there are those that know me only for the web stuff. It's interesting seeing that Balkanization.

I remember a talk we did during the tour at

Auburn University in this well-appointed room at their big library. It felt as if every single person in this room knew me as a different person. It was like all the McCloud tribes had converged into some great summit.

SPURGEON: Were there any technical difficulties in getting this work together? Or were all of those problems overcome with the Kitchen Sink editions?

McCLOUD: There was a gargantuan technical challenge for me, in that I only had Photostats of some pages, originals of some pages and neither of some pages, which meant I had to resort to the printed copies.

SPURGEON: Wow.

McCLOUD: First of all, the challenge was scanning them in and making sure they were all the same size. Then, because I'm picky, I also had to equalize the line weights in Photoshop. I would make a pretty complex series of adjustments and often hand-tooled fixes to make sure that the pages looked more or less that they came from the same source. This involved sometimes applying filters to the lettering separately from the lines. It was a pretty gargantuan job.

SPURGEON: How long

a job was it?

McCLOUD: That part of it took up a good six weeks of continuous work.

SPURGEON: Oh my goodness.

McCLOUD: But it was worth it. It looks pretty. And now when I look at it I don't want to throw it against the wall like I do with some of my books.

SPURGEON: Is it nice in general just to have this work in one place, to be able to point at a book and say, "That's where it is"?

McCLOUD: I love it. I think I'm just obsessive-compulsive enough that having things in scattered places eats away at me. Having it in this one singular package is very gratifying both to my practical side and to my psychoses.

SPURGEON: [laughs]

McCLOUD: The fact that it's a very attractive package helps. I like the size of it. Like

Frank Miller, I think that comics are too damn skinny. The trim size that became the standard in the industry, it's just a little too narrow. It doesn't feel right. So I had the opportunity to make it a bit squarer and slightly smaller, because I think it handles better at that size.

I was particularly fond of the cover we ended up with. I had a more conventional cover that had that same illustration, but it was in the middle and the logo was at the top and I had this more muddled green and gold scheme. My editor at Harper, Hope Innelli, very late in the process asked if she could just take one last crack at this vague idea she had in her head. She came up with a black, white and silver design with the logo and illustration switched. I knew almost instantly that it was infinitely superior to what I had come up with. [laughs] I said, "Yes, let's go with it."

I was really grateful to them, because it was clear that if I had said no that would have been the end of it. It was just so beautiful. Every time I look at it, it just makes me smile.

SPURGEON: The thing that pops out at me about that cover is the dates: 1987 to 1991. [McCloud laughs]

SPURGEON: The thing that pops out at me about that cover is the dates: 1987 to 1991. [McCloud laughs] Understanding Comics

came out two years later, in '93, right?

McCLOUD: Exactly.

SPURGEON: You were a machine, Scott! From like '87 to '93 you were a page-producing machine! [McCloud laughs]

McCLOUD: Maybe on some levels, but really I had a lot of deadline troubles during that time.

SPURGEON: I guess when I see all that work in one place it looks like a lot of comics but according to the standards of the time, you were one of the irregular guys.

McCLOUD: Exactly. The ultimate example being the infamous Zot! Month when

Eclipse had planned several things around Zot! and none of them came out during Zot! month. [Spurgeon laughs] It was the most terrifyingly embarrassing thing that ever happened to me as a pro.

SPURGEON: Is there anything to be said for working in that fashion even though you felt behind most of the time?

McCLOUD: I think the biggest difference was that there was this disjuncture between my potential and my delivery. There was this scraping, this friction, and you could see it in the panels where it looked like I was asleep at the wheel. You could

see that parabola of panic that I think most cartoonists are familiar with, where you begin at a pace where you have to do a page every two days, and then gradually it becomes a page a day, then two pages a day then three pages a day.

As a result, it was just uneven. Some of the worst, most offensively incompetent faces and figures came out of those panic periods. When I began

Understanding Comics, and especially in my later projects like

Making Comics, I became much better at estimating how much time it would take. It helped that the advances I was getting were enough to cover our living expenses while I was working. I became pretty punctual.

Understanding I think I went slightly over. But with projects like

Making Comics, I was delivering on time.

The amazing part is, through careful management of caffeine, and incredibly long work hours, my productivity curve was almost flat. I would begin with a little more than a day per page, and I would end with a little more than a page per day. That to me was extraordinary. And I was getting enough sleep every night. And my productivity didn't dip at 3:00 pm because that's when I would have a Dr. Pepper. I had figured it out. I'm much more efficient these days.

SPURGEON: I wonder if anyone's ever looked at the dysfunctional nature of deadlines and the nature of productivity and what that's done to artists over the years. You get the sense even with some mainstream artists that there are talented people that kind of rattled and fell out of the industry because they couldn't ride that wave for more than a couple of years.

McCLOUD: Many relish the late-night, 3:00 AM panic, because that can produce a feeling of near-euphoria. What I found seemed to work much better was marathon-and-rest, basically. Take a year of seven days a week, 11 hours a day, but then rest for a time. It's tough on the family, but then when I'm done, there's some relief. Then, when I go back into marathon mode, I go back with a great deal of energy and even a certain degree of joy. I find myself loving to sit down at 8:00 AM each day. To sit down in front of that screen and work. I love the process, and I don't feel tired.

SPURGEON: I recently wrote a short essay about this book where I talked about how I saw an emotional underpinning to Zot!

and I was confused because the introductory material in this volume didn't unpack or explain this, I guess according to my demands as a reader this be done. [McCloud laughs] I think you nailed a kind of longing and boredom that kids have, and you've said since that perhaps this was something that you drew on from friends and their situations. It wasn't something from your own personal experiences, necessarily.

McCLOUD: In your review the overarching question is how much of this was scooped right out of my own emotional experience and how much did I have to extrapolate? If you think about it, we're in grade school, most of us, for about 12 years. And over the course of 12 years, virtually anybody is probably going to accumulate enough genuine anguish. If you had one really bad day, you can probably do a reasonably good job -- provided you can remember the texture of that day -- of extrapolating to someone else's really bad childhood.

I would have to rate my childhood as maybe a 7. It was reasonably happy. In elementary school I belonged to an advanced program so in class, I was surrounded by kids that if anything were smarter than me. On the playground, though, I did get bullied. I guess we all did. [laughs] All the kids in the AP program probably got bullied. So I knew what it was like to really, genuinely have my ass kicked. I was kicked in the balls at one point by this kid that was supposed to be some kind of hall monitor. I was kind of terrorized here and there. For the most part, though, it wasn't too bad.

In Junior high, I was still being a nerd with my pals like

Kurt Busiek, but I also learned to disappear. I learned the art of gaming the system so as to seem ordinary. In high school, because we lived in a really smart town, I wound up falling in with the nerd core, which was kind of huge. There were enough children of engineers and scientists and newscaster and politicians and journalists and professors that we had an entire cafeteria filled with nerds. So that was really liberating. I kind of portray that a little in

Zot! also.

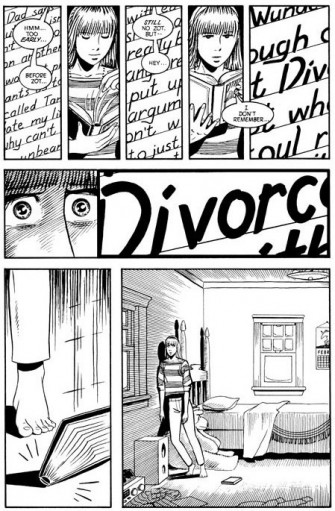

Of all of the things that I portray, all of the real serious problems that people have, the only one that I didn't experience first hand at all was the pain of parental discord. My parents got along pretty well. If they fought, they were good at hiding it. So the potential divorce that's sort of at the center of Jenny's world, and the real dysfunctional parents that a few of my characters have, those I did have to look to my friends for.

SPURGEON: Was there any desire on your part to deal with the question of how kids escape, how kids negotiate those harsh times through the kinds of fantasies represented by Zot and his world?

SPURGEON: Was there any desire on your part to deal with the question of how kids escape, how kids negotiate those harsh times through the kinds of fantasies represented by Zot and his world?

McCLOUD: I think on one level I was a bit cold in my approach to that theme. I was working on a detached level of thinking. "Well, this is what the story demands. These are my themes. Let's see if I can work with various themes and variations on that." I was trying to conceive of these things as a writer. "What would a writer do here?" [laughter] So I wasn't as emotionally invested in it.

I've always been fairly agnostic on the question of escapism. I saw escapism as a valid option. At the same time I was wrestling with the validity of escapism in my own writing. I saw all these non-genre comics outside my window and wondered if I was on the wrong train. [laughs] As a kid who early in college was reading

RAW, I secretly feared that by its nature my mission was doomed to be a little bit more trivial.

It's helped, as a parent, to be in a family of nerds. My wife and my two girls are total fangirls. I've seen what a great experience it is to just bask in the warm glow of escapist entertainment.

Buffy and whatnot. So I've sort of forgiven my previous self. But I think I do still want to try and play in that other arena. Does that make sense?

SPURGEON: Sure. To poke you a little further, it's clear there are people with a great deal of affection for this series. It's not just about

escapism; it functions as escapist literature for some of those people. There are fans of this work that are more into it than you are.

McCLOUD: [laughs] Yeah, you were very astute in making that observation a while back.

SPURGEON: Did you mean for the work to be taken that way? You have these mixed feelings towards escapism, but you created this work that's a very powerful piece of escapism.

McCLOUD: I wanted it to be. But it's an escapism comic by the guy who was going to write

Understanding Comics. I was trying to figure out what kind of rocket fuel would drive this thing. I wanted it to be a very effective form of escapism. But I was doing it through the manipulation of certain archetypes, storytelling tropes, and the effect of certain drawing styles. I was a scientist. The scientist in me had this storyteller chained up in the basement. [laughs] I was making what use I could of my intuitive storytelling persona to harness that stuff. That was the real fuel: the less scientific more emotional side of myself -- but the formalist was still driving the bus in a lot of ways.

SPURGEON: Now, certainly the experience your kids are having is very different than the one you and Kurt lived through when you were kids.

McCLOUD: Yeah.

SPURGEON: Did you get any sense when working with this material again how much of it was of a time? For instance, you also mentioned that there was some nuclear dread informing parts of it. That might not be as much of a factor now.

McCLOUD: I don't think that the nuclear dread part necessarily dates it. Now that we have the book all in one place and I can look at it from enough emotional altitude, I have to say I feel as if it's less dated than other things of the era. I think I tried very hard at the time to create work that would last. I think I was maybe aware more than my peers as to aspects of what we were doing that were tied to our time. I was trying to steer clear of those.

SPURGEON: Is there an example of that that pops into your head? Especially if it ends up with you insulting someone else's work. [McCloud laughs] I'd like that a lot.

McCLOUD: I wish I could do you that favor. [Spurgeon laughs] If you look at the other titles that could be most closely associated with me of that era, the ground-level middlebrow alternative superhero variant type titles, many of them were about genre. If there's one through-line in what I've been doing all along it is I actually don't give a fuck about genre. I can enjoy something that plays with genre, but almost everything I've ever really valued stands outside of any given genre. I look at my favorite movies, like

Run Lola Run or

Princess Mononoke or

Fight Club, and I realize they're very hard to shelve. I think

Zot! at the end of the day is kind of hard to shelve. That makes me happy.

SPURGEON: Was that just you being contrary?

McCLOUD: No, it was my trying to find something earnest, something without the irony of the moment, without the winks and the nudges and the affiliations: the different ways that works of narrative call out their origins, or play on them. The way that they require that you already be in this moss patch of pre-existing genre trappings so that you can appreciate "Ooh, they went that way instead of this way."

That's such a muddled answer. I tried to create characters that were basic archetypes, or basic human thoughts. I tried to create villains that were based on ideas about the future that were fundamental, like the idea that our machines would become us or that we would become our machines. All of those things were really an attempt to create something that wouldn't be washed away when fashion changed.

SPURGEON: Two contexts that have

changed for the book is that there was almost no young-adult aimed material at the time. That is a huge category now. Another difference then and now is that some of the storytelling techniques you used common to manga were not part of the visual vocabulary when Zot!

was coming out but may be more prevalent now. Do you think either one of those factors changes the reading experience?

McCLOUD: History in some ways has caught up to the book. The manga techniques I was using were at the time pretty rare in American comics. Now they're more mainstream, although I'm still frustrated in that people seemed to have picked up on just the surface stuff. In terms of the young readers aspect, it's nice to think that

Zot! might be a bridge book for kids that read

Bone, or

Baby-Sitters Club or whatever. I imagine that the superhero trappings might stop a lot of them. There are a lot of readers that never read superheroes. That go straight from

Fruits Basket to... I don't know what.

SPURGEON: One reason I wonder about the work being perceived differently than it might have been then is that back then it was processed in large part in terms of how it broke with standard superhero tropes. It was a subset of superhero readers because that was almost the entire audience back then.

McCLOUD: Here I'll actually name names: if you compare it to

Don Simpson's Megaton Man or

Jim Valentino's normalman, both of those really worked in a way that referenced where they existed vis-a-vis what had come before. Sure you can look after the fact and say, "Okay,

Zot!existed to the left of this and to the right of that, above this, below that, comparing it to

Marvel or

DC or

American Flagg! or

Nexus or whatever. But I really wasn't thinking about that. I was just cracking open

Osamu Tezuka. I was trying to channel my childhood. Where it stood in relation to the other comics on the shelves at the time was more of an accident than for others working in a similar vein.

SPURGEON: Have you heard from anyone who's picked this book up brand new and read it?

McCLOUD: Random people: reviewers, people that saw me talk and bought it and wrote me a couple of days later. One of my missions with this book was to erase some of the embarrassment I felt about this material. I could go back and fix the worst parts of it. When I hear back from people, people don't just see it for its problems; they have a very balanced view of it. I haven't yet heard the complaints I thought I would. "Oh yeah, Mr. Making Comics [laughs] you can't do, so you teach." I haven't heard that.

SPURGEON: That's good.

McCLOUD: Yeah, it made me feel good. Oh, and by the way, the reason that the dates are on the cover? It's kind of ungainly, having the dates there. It's because I was terrified that somebody would think it was the thing I did right after

Making Comics.

SPURGEON: [laughs] That's horrible. And it's horrible that I laughed. [McCloud laughs] Hey, I wanted to ask you a nerdy question that came to me while re-reading

SPURGEON: [laughs] That's horrible. And it's horrible that I laughed. [McCloud laughs] Hey, I wanted to ask you a nerdy question that came to me while re-reading Zot!

I thought that the character designs held up pretty well. That's not something you have occasion to do -- other than your narrator stand-in I don't think of your work in terms of its character design.

McCLOUD: Yeah, I haven't gotten to do that in a long time.

SPURGEON: Are you happy with the way the designs look?

McCLOUD: If you asked me in 1988 about my strengths and weaknesses, I would have said figure drawing was a weakness and character design and layout were strengths. I felt good about that stuff then. Still do. Little things like making sure the eyes are all different. I'm a big crusader against the cookie-cutter approach. Even very talented cartoonists have templates for their characters. I hated that. I wanted every character to carry their own stories on their back and be their own universes. Ensuring those differences was very important. It'd be hard to find two characters that have exactly the same eyes. With the broad characters, the villains, I was going for something where every part reflected the whole, so that they have this instant impression -- just looking at them I wanted them to have a particular effect, like they stepped out of a dream.

I have to give props to

Paul Rivoche. When I was working on the proposal for

Zot!, he was putting up

those posters of Mister X. I thought

Mister X looked like it was going to be an amazing book. I knew it would be out well before

Zot!, so it would be okay that I was pilfering some of the design aesthetic. [laughs] I think 9-Jack-9 was partially inspired by that poster he did of Mister X, where he's sort of in the background and the glasses are reflecting the light or whatever. I actually felt bad when

Mister X didn't come out until after

Zot! Rivoche never even drew it.

SPURGEON: Those posters were something, though.

McCLOUD: They were. I created color posters for the proposal; I'm not sure anybody saw them. It was partially in response to that, the idea that a character's image could be just as iconic as a movie poster or a trading card.

SPURGEON: I want to shift gears a bit for the last few questions. You did some work on creators rights issues once upon a time, and were part of the original crew putting together the Creator's Bill of Rights. The golden goose of media rights seems to have put a lot of those issues back into play. As a result we're seeing a lot of cartoonists that don't seem to understand those concepts in a way that your generation did, or not caring, or even asserting it's no one's business if they want to sign a horrible contract. That it's their god-given right.

SPURGEON: I want to shift gears a bit for the last few questions. You did some work on creators rights issues once upon a time, and were part of the original crew putting together the Creator's Bill of Rights. The golden goose of media rights seems to have put a lot of those issues back into play. As a result we're seeing a lot of cartoonists that don't seem to understand those concepts in a way that your generation did, or not caring, or even asserting it's no one's business if they want to sign a horrible contract. That it's their god-given right.

McCLOUD: Well, it is. I'm not sure that that part is all that different.

SPURGEON: Okay. [laughs] Do you follow these newer conversations?

McCLOUD: I'm keeping an eye as to what's going on, particularly the web ventures. Things like the

Platinum deal, and what

Tokyopop has done. We're obviously heading down the same road. It might be helpful to have a set of rights circulate among the communities. My feeling was that the rights in the Creator's Bill of Rights were fundamental and that each of us could choose as individuals and say, "These are the things I shouldn't be signing away at all." But it was always an opt-in thing. I didn't see anyone having the responsibility to sign onto this for the good of the community. It was a very libertarian impulse. It was waking up to this enormous amount of power in your hands, and just exercising it.

SPURGEON: Are you surprised these issues have to be re-argued? I think there was a sense 20 years ago that once these issues were brought to light they would serve as a bedrock for future discussions to build from there. They would endure.

McCLOUD: Things were actually quite stable for a while. In many respects throughout the late '90s creators rights were used as a matter of course. People expected to get their originals back. They expected to be able to use a lawyer for negotiation. They expected to have the rights of ownership and control.

You have to remember there are two crosscurrents and they go to extremes on both sides. On the one side, you have people trying to snatch up rights in the old-fashioned way. Like Tokyopop. And then you have webcomics artists making literally 40,000 comics -- and I'm not throwing this figure out to impress anyone, it's apparently true -- that are acting like 40,000 little

Dave Sims. They have absolute control. They have no strings on them at all. They can put whatever they want out there. They have control over their distribution. We sure didn't. It's a lot like the evolution of Fair Use, which has become more restrictive in some corners and evaporated in others.

The conversation is far more vigorous and omnipresent than it used to be. When we did the Bill of Rights, we got the cover to the

Comics Buyer's Guide the next day, and eight months later

The Comics Journal wrote about it. [laughter] Compare that to something like the Platinum deal, where you had something like 700 zillion words posted on message boards and forums and sent out in e-mail in the space of a few weeks. People like

Scott Kurtz were weighing in. If someone like

DJ Coffman wants to take the plunge, he's doing so in an atmosphere of full disclosure.

SPURGEON: Is there a chance that the democratization of the dialogue harms the quality of that dialogue? There was something impressive about getting those issues of CBG

and TCJ

-- a kind of "You should pay attention to this" that doesn't exist when the argument is being shaped on a message board.

McCLOUD: The equivalent gesture in the current climate would be if three or four of the majors got together and released something together. If you,

Heidi and

Dirk all agreed on something, we would notice.

SPURGEON: Because the world would end. [laughter]

McCLOUD: But you know what I mean? We still have vetted sources, respected sources. The process just goes faster. The discussions devolve almost immediately into that mulch of he said/she said, endless debates that always end with someone being compared to a Nazi, but you still have ideas that remain and make a difference.

SPURGEON: I saw you at San Diego this year; you didn't see me. You were going from one segment of the floor to another. You were in a hurry. It occurred to me you're someone that is insulated from a lot of the heave and fall of daily business in the current comics climate. You're not creating comics in a way that you want to be a writer on a TV show or expect to have three movies picked up suddenly.

SPURGEON: I saw you at San Diego this year; you didn't see me. You were going from one segment of the floor to another. You were in a hurry. It occurred to me you're someone that is insulated from a lot of the heave and fall of daily business in the current comics climate. You're not creating comics in a way that you want to be a writer on a TV show or expect to have three movies picked up suddenly.

McCLOUD: Probably not.

SPURGEON: Given where things seem to stand, is there anything to be said about the state of your creative profession right now? From your perspective, do you still work in a good place? Is it crass, over-commercialized, not as wide open...?

McCLOUD: I think it's a good climate with one huge exception. That sector that could previously make a living: that's beginning to erode for some creator-types. It's easy to see that this economy could slide, and that part of the industry could dry up.

SPURGEON: Wait, which market are you talking about?

McCLOUD: All of them, that's the point. [laughter]

I like that we have an economy of free and DIY and a growing market for graphic novels and an all-ages movement. Although the manga scene doesn't have an effect on too many creators here, there's that, and there's the traditional superhero realm. Diversity is healthy. When you have more diversity in the marketplace, it's healthier. When you don't, you have crossbreeding and degradation. It's hard to find another period of history in comics in North America where you've had this much diversity, maybe by a factor of three or four over the last few years. It's pretty astonishing.

The problem is that in a few years this may result in a diversity of ways to make

no money. [Spurgeon laughs] To me, that's the sole danger. I have a problem seeing any other downside.

SPURGEON: It may be less diverse than the market we had in our heads.

McCLOUD: I don't know about you, Tom, but it's pretty close to the market I was dreaming about in 1988.

SPURGEON: I guess what I saw when looking from my outsider's perspective at my comics and cartooning friends at various shows this year is that we've progressed past the point where we're no longer inhaling the fumes of the promise

of big-time publishers' interest, the promise

of Hollywood, the promise

of monetized web publishing. Instead, it's the reality of those things.

McCLOUD: Okay, I'll grant you that. I do think there's a sense of slowed momentum.

SPURGEON: I'd suggest it's maybe a "I don't have a place here" feeling. That although things are better overall, that not everyone gets to be on board. Now if this were my interview and not yours, I could go on in fascinating detail at this point.

McCLOUD: [laughs] I think this might be the first San Diego in a little while where people could look at the situation and see that some of these trends have peaked. That wasn't true last year or the year before.

SPURGEON: And if you haven't gotten on the other side yet, that could be worrisome.

McCLOUD: The tide is going back out. That can be a very frightening thing. I saw a furtive look here and there.

SPURGEON: Another thing: I spoke to Daniel Merlin Goodbrey a while back, and I remember him as a person you were high about during your advocacy for early webcomics. It occurs to me that that realm has severely changed since then, that the dialogue back then was about the possibilities of the form, or just wrapping your mind around these new comics. Now when I talk to people, it seems the dialogue is dominated by the idea of monetization.

SPURGEON: Another thing: I spoke to Daniel Merlin Goodbrey a while back, and I remember him as a person you were high about during your advocacy for early webcomics. It occurs to me that that realm has severely changed since then, that the dialogue back then was about the possibilities of the form, or just wrapping your mind around these new comics. Now when I talk to people, it seems the dialogue is dominated by the idea of monetization.

McCLOUD: There were a lot of creative possibilities for experimentation early on. There still are. The difference is that in 2008 no one is proposing ways for the experimental weirdos to make money. I was back then, and it failed. Right now almost all of the successful business models are built on daily or thrice-weekly gag strips. Short attention spans. Those include some extremely talented people and some great comics. The point is to have a lot of chatter around the comic. The comic as social space. It's this little centerpiece on this potpourri of appetizers and party favors that make the money: advertising, merchandising, sponsorships, t-shirt, mugs, that kind of thing. If you wanted to do the equivalent of

Jimmy Corrigan on-line, or

RAW... it doesn't really lend itself to that model yet.

The alternative models like subscriptions and micros were a non-starter. Guys like me failed to come up with something for long-form comics. But guys like the

Penny Arcade guys or Scott Kurtz have done really well by the short form comics.

SPURGEON: You say "yet," but isn't it hard to break out of this kind of reward pattern?

McCLOUD:

McCLOUD: We may get locked into certain models on mobile devices, but in terms of the overall web an alternate system or revenue model can still present itself. Nobody's fighting over one finite patch of ground: the ground is essentially limitless. So that doesn't worry me so much. The fact is, I don't have the answers now, so I'm going to go off and draw a graphic novel. I'll see how things look when I get back.

SPURGEON: Does having a new book out put you in a different place to create?

McCLOUD: Psychologically, it was healthy for me before I came back to fiction in a big way to get a handle on what I thought about my first attempt. I have some really mixed emotions about my work from 20 years ago and its relative worth in the scheme of things.

Having fought through those feelings and getting some perspective on them, I'm better able to move ahead, not look in the rear view mirror, not have those doubts that come with new enterprises. I can return to fiction knowing that I've learned a lot in 20 years.

*****

* cover to new collection

* McCloud-drawn McCloud icon

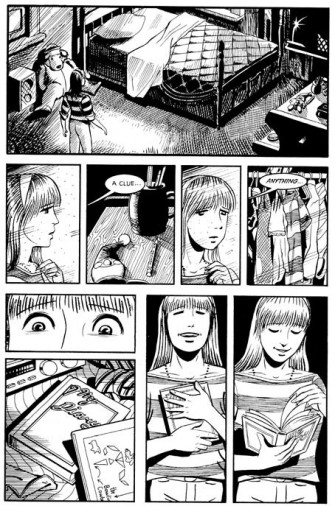

* Jenny Weaver as designed by McCloud

* the covers to the last black and white sequence in the Zot! comic book series

* key two-page sequence from book

* Zot! as designed by McCloud

* 9-Jack-9 as designed by McCloud

* Creator's Bill of Rights TCJ issue cover

* the interface to an on-line Zot! comic

* Uncle Max as designed by McCloud

* photo of McCloud at 2003 San Diego convention

*****

*

Zot!: The Complete Black and White Collection: 1987-1991, Scott McCloud, HarperCollins, 576 pages, 9780061537271 (ISBN13); 0061537276 (ISBN10), July 2008, $24.95

*****

*****

*****

posted 1:00 am PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives