Home > CR Interviews

Home > CR Interviews A Short Interview With Joe Sacco

posted January 25, 2008

A Short Interview With Joe Sacco

posted January 25, 2008

*****

What's not to like about Joe Sacco? One of the few cartoonists in the last 25 years to whom you can give credit for an entire way of doing and looking at comics through the notion of comics journalism, Sacco's funny, intelligent and his work is consistently excellent. There is nothing that makes me happier about the shape of comics over the last decade and a half than that Joe Sacco has a prominent place in it. I talked to the cartoonist, who is currently hard at work on another major piece which will likely be seen in 2009. Fantagraphics has released a hardcover

Palestine: Special Edition, which is the subject of most of what follows. It's a nice-looking book, with excellent back material and even some lacerating self-analysis from the author. The story itself proves to be one of those rare comics efforts that's grown in power with age, and it was pretty damn considerable upon its initial, serial publication. I had a great time doing the interview. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: Is there a reason why you're doing this project right now? How did the project come about?

JOE SACCO: I think

Eric [Reynolds] came up with it and passed it through

Kim Thompson and then one or the other contacted me and said, "How about this?" What sounded good to me is that they were going to put the book in hardcover. Maybe I've related this story to you before. A long time ago I asked Kim if they were going to release this in hardback. And Kim said, "Yeah, we could do that, or we could go to the top of the Space Needle and throw out buckets of money." [Spurgeon laughs] To me, the idea of having a hardcover, it was like, "I arrived." The idea of this thing as a money loser, now it actually makes them money. It just made me feel sort of good. And I think, "Why not? It should be in hardcover." I wanted it to be in hardcover originally. But it really wasn't worth the hardcover before for commercial reasons. And now it is.

If you're going to put something like that together, then of course you think, "Well, maybe there should be some extras." I'm a little ambivalent about it. Part of me feels like I'm interested when other people explain their work, and part of me feels like the work should always speak for itself. I decided to go along with it, because basically I feel that so many ask me these sorts of questions about my working methods. I talk about this stuff. If I'm going to talk about it, I might as well be honest about it. I might as well demystify it to some extent. So that's the purpose of all the extra information. Comparing my photographs to the drawings, having excerpts from my journal entries, just so people can get an idea of how I go about doing things. Maybe they won't ask me those questions in interviews anymore. [laughter] It'll be there for them to read.

If you're going to put out a hardcover in this day and age, people sort of expect some extras. They don't want to buy the same book again. This is sort of an impetus for them to say, "Okay, well, the softcover's falling apart. Maybe it'd be nice to have this volume." Fantagraphics did a beautiful job. Adam Grano, he did a great job with it. So why not, I guess. But there was no real reason why this was the moment to do it.

SPURGEON: I was impressed by the supplementary material. I thought it among the best I've seen; almost certainly it's the best I've seen in a comic in terms of the quality of insight.

SPURGEON: I was impressed by the supplementary material. I thought it among the best I've seen; almost certainly it's the best I've seen in a comic in terms of the quality of insight.

SACCO: I'm glad to hear that, because I don't look at supplementary materials of other people's work, really, I can't even remember looking at some stuff like this. My thing is I relate it to CDs, and how when I was first buying CDs, I was always into the bonus track. Now I can't stand that stuff. Unless it's something really revelatory and interesting, it's just wasting my time with alternate takes, and it's like, "Give me a break. I don't want to hear that stuff."

SPURGEON: It looks like it was time-consuming. Even if people hated everything that ever came out of your pen, they would have to admit you really spent some time digging into the older material and related issues.

SACCO: It was a lot more work than I thought. Once you get started on a project like that, you think, "Is this going to be half-assed, or am I actually going to put some effort into it?" My feeling is if people are going to be spending any more money on this thing, it better be worth it. I'm always thinking in those terms. I really think commercially in a way. Not just in the sense of "Okay, I need some money, so this is a good thing." But also if it's going to be a bargain for the reader. I feel like people deserve a bit of a bang for their buck. So yeah, I put some effort into it. And there was a

lot of back and forth about the design. And yeah, it took a lot of digging... always trying to go that extra step, even though this was kind of my off-hours project.

SPURGEON: Another thing re-releasing a work allows you to do is to look at the work again with new eyes. I guess we'll see how readers react, but there were moments in the supplementary material where you indicated your own thoughts about re-visiting that work. Was there a process of re-reading the book anew? It seems like it might have been an interesting experience for you to go back and look at this important work for your career.

SPURGEON: Another thing re-releasing a work allows you to do is to look at the work again with new eyes. I guess we'll see how readers react, but there were moments in the supplementary material where you indicated your own thoughts about re-visiting that work. Was there a process of re-reading the book anew? It seems like it might have been an interesting experience for you to go back and look at this important work for your career.

SACCO: That's true. To be honest, I've never read the book all the way through since it came out. I've read parts of it again. Sometimes I'll open it up for some reason because I need to refer back to it for whatever reason, and I'll sort of lose myself in it for five or ten pages. There's some sections I almost know by heart, because I've actually looked at them again and thought, "Could I ever capture this atmosphere again?" Sometimes I see it as the standard that I'm not sure I ever met. Sometimes I see great problems in the work or things I would really change. I think that's typical. You see things and you think, "Oh, I could never match this." And you see other things and you think, "Boy, I've really improved." [laughter]

The thing that struck me the most... Whenever I look at it again, I realize how much writing was important to me, making words sound good. Making it sort of entertaining and moving it along in a way. And I know, just because my work has become more self-conscious, that in some ways I've downplayed that or turned the knob down on that. You realize with comics that the pictures have to speak more, and sometimes you can write a really nice passage, and the wording can be really nice, but sometimes that can get in the way of the strict journalism of it. Now when I edit my scripts I'm much more ruthless about cutting things out. Because I just want the thing to move. What

Palestine had is a different kind of energy to it. In some ways, I don't know if I'll ever be able to write like that again with strict journalism. I think some of that was in

The Fixer in a way. I was able to sort of write, because I love words, be able to let myself go a little with the writing there. In other projects I'm doing like the one I'm doing now and even the Gorazde book [

Safe Area: Gorazde], I was much more restrained.

SPURGEON: You make the point about the work's energy in the supplementary as well. I was struck by that, because it lines up with what I hear about the work. A reason a lot of people I know hold

SPURGEON: You make the point about the work's energy in the supplementary as well. I was struck by that, because it lines up with what I hear about the work. A reason a lot of people I know hold Palestine

so dear is that it has this kind of careening energy to it, this reflection of a very specific experience, a flow that doesn't appear in any of your work since. I was almost amazed that you would pick up on that, too.

SACCO: If you look at my work subsequent to it, you'll see elements of

Palestine in there, some of the craziness of the angles and all that. Which actually really comes from my

Yahoo books. If you look at the

Yahoo material, I think that's where it really comes from. It sort of reached full fruition in the

Palestine work. I just use it when it's really necessary now. I think that sort of manic energy that's in the

Palestine book really reflects in a way who I was at the time and how I was approaching the material. I was much more jumpy. Much more overwhelmed by the things I was seeing and how I was trying to get the story. I was unsure of myself. Not so much in the drawing, but when I was there. And it reflects that.

Now when I do these sorts of work, I'm just more experienced, so I'm more low-key. Panic isn't the word, but I don't frighten as easily. So the drawing reflects that. The drawing reflects a shift in my maturity. It's not because I don't appreciate who I was during the

Palestine phase. I think that stuff is entirely true to who I was. But if I used all those techniques in that same kind of way, I think that wouldn't be true to who I am now. If that makes me works now perhaps slightly drier, that's just how it goes. I accept that.

SPURGEON: Has there ever been a serious backlash anywhere to Palestine

that you know of?

SACCO: Not serious. Every now and then I feel like someone comes down on it, or some store gets in trouble temporarily. I know that some places don't carry it because it's the personal viewpoint of the owner. Which is the prerogative of the owner. But no, no.

SPURGEON: Some of the things you hint at in the supplementary material made me wonder. There was one remarkable anecdote where you talked about someone reacting negatively to the caricature aspects.

SACCO: Yeah. There was a Palestinian-American person who tore up the book without really reading it. When something like that happens, I'm not the kind of person who goes, "Well, fuck you." I'm the sort of person who thinks, "Does this person have a point or not?" You kind of examine it or weigh it.

SPURGEON: One thing about Palestine

is that you were left alone during its creation, which I think may have contributed to a cohesion that it seems to me would be harder to maintain in subsequent projects.

SACCO: I don't know, because I'm working on a project now that's probably the most ambitious thing I've ever done. I think any cartoonist who's really doing good work is going to tell you it takes extraordinary discipline to keep it up, day in and day out, year after year. So I still have it in me. Honestly, you always wonder if you'll have it in you when the one you're working on it's done. Because when you're working on it, as much joy as it gives you, and as much drive as you have, it's so difficult you don't know if you're going to be able to do it another time.

SPURGEON: A lot of what's been written about you has been in terms of your approach, the fact that you pursue journalism in comics form. Are you surprised that there aren't more people doing exactly what you're doing? You see the occasional first-person report and comics essay, but almost no one in more considered journalism. Do you feel a kinship with anyone out there?

SACCO: I know people like

Ted Rall have done something along these lines, and it seems like magazines are open to cartoonists doing 1-, 2- or 4-page strips.

Art Spiegelman at

Details was sending people out to do some journalism. There are a number of French cartoonists where I think their work is journalistic. I don't feel like I'm the only one doing it. What I do know, and I'm not claiming any title for myself, what I do know is that when people want to talk about comics journalism, they tend to call me up. I'm still kind of the go-to guy, for whatever that's worth. In some ways, that's flattering. It doesn't really matter, because you wrestle with your work all the time and you know your own limitations. You know how things can be better. So you put everything into perspective. [laughs]

SPURGEON: Is it ever a concern for you that you might write more for an audience now because, well, you

SPURGEON: Is it ever a concern for you that you might write more for an audience now because, well, you have

an audience now?

SACCO: I don't think that enters into my thinking. I was definitely aware when I was doing

Palestine it sold so miserably as a comic book that I was able to do it under the radar. The good thing about selling miserably is that no one has any expectations. No one is talking about your work. And no one is criticizing it, [laughs] I mean, not in that way that really matters. I was doing it, no one was really buying it, and then it came out in a book, and it became successful as a book after the Gorazde book became successful. If I'm not mistaken, the soft cover single volume came out after the Gorazde book came out.

SPURGEON: I'm almost certain of that.

SACCO: So I'm aware now that people are interested in my work. I just try to use that to my advantage. I do those shorter pieces you mention for magazines. That to me is almost ideal. I don't know any other term for it, but I like to be in the field. Those magazine pieces allow me, when I do them, to sort of go somewhere and get a story. I have a lot of interests. That doesn't mean I won't work in the long-term format again. But I'm also interested in doing shorter pieces. It keeps your blades sharper when you can do that. Here I am sitting at my desk and I've been almost sitting for five or six years. Okay, I made a trip to Iraq that was pretty short. I was gone three weeks. In five or six years you're sitting there just drawing, drawing, drawing. Anything you do a lot of you're going to be better at. What I'm not doing a lot of is journalism. And I miss it.

As far as what people expect... you know what I've noticed? Whenever I do something that's maybe more humorous, people think, "Ah, this isn't serious stuff." That's what I'm most aware of. As far as my journalism goes, I don't really pay attention to what I think people want, although I know they might be more interested now, certainly. It's not like I'm paying attention. What I think about most is, "Can I ever do anything other than this and have people take it seriously?"

SPURGEON: Really?

SACCO: Yeah. What if I wanted to do fiction or some sort of essay stuff? I think people would say, "OK, that was whatever it was, but his real serious work was this, this and the other thing." And it is my real serious work, but a personality has more in him or her than serious work. [laughs]

SPURGEON: Do you think you'll eventually move in that direction anyway?

SACCO: Yeah, I think so. At the very least, what I think I'm going to do is try and balance it a little. There are other things I want to do.

SPURGEON: I saw some photos that Eric Reynolds put up of your recent appearance at the Fantagraphics bookstore. I don't know if that's an appropriate hook on which to reflect, but it occurs to me you have a very different profile than you had in the 1990s that is not just reflective of the growth your career has had, but kind of the way that comics are treated now differently now than 10-15 years ago.

SPURGEON: I saw some photos that Eric Reynolds put up of your recent appearance at the Fantagraphics bookstore. I don't know if that's an appropriate hook on which to reflect, but it occurs to me you have a very different profile than you had in the 1990s that is not just reflective of the growth your career has had, but kind of the way that comics are treated now differently now than 10-15 years ago.

SACCO: Yes. That's definitely true.

SPURGEON: How is it different for you? Do you ever reflect on how things are different for you now just as a functioning professional? Palestine

was such an odd duck in its comic book iteration, and now there seems a much greater context to appreciate what you're doing.

SACCO:

SACCO: The difference between the days I was working on the

Palestine comic book and now is like night and day. Comics, the way they're perceived and the way they're treated, it's almost hard to imagine it's the same medium, or the atmosphere is even the same. What you're breathing, the air you're breathing now is very different than what it was then. Back then there were people doing good work and working at the top of their game, but it seemed at around the year 2000 everything seemed to coalesce. There was almost like enough stuff was coming out that was serious or really well done, and people sort of just turned their heads and thought, "Oh, there's a bunch of this stuff." It doesn't mean there wasn't stuff before, because there was, and there are a lot of people that did a lot of serious work that will be mentioned years from now as a precursor or whatever. Things have changed a great deal. I can make a living off it now. And back then... thank God I was doing the

Palestine books when I was in my early 30s. Now when you think about it that's pretty old to be doing something like that. I was still at the point of renting a room for $250 and that kind of thing.

Things have changed a lot. It doesn't mean it's easy financially. But it's much, much easier. To me that's a big deal. If things work out for you financially, you're more apt to continue on the same path. If you're getting rewarded for what you're doing, you think, "Okay, I'll keep doing this. I love doing this." But there came a point in the middle of the Gorazde book where I thought, "I'll finish this book, and then I'm wrapping it up. I'm not going to do any more comics." How long can you beat your head against a wall? Those are the subjects I'm interested in. I thought if I did humorous work it wasn't what I wanted to do right then. I was interested in these very serious subjects. I didn't have anything in me other than that. I saw how

Palestine had done. I thought, "You know what? I can't keep doing this. I can't work this hard and make this amount of money. I can't even have a personal life." It was kind of like that. So I was actually half-seriously thinking about becoming a mathematics teacher. For me, math is pretty easy, so doing something like that and that's it. That's the difference. The difference is now magazines call my agent -- I have an agent now -- and say, "Is he interested in doing this?" People are contacting me relatively frequently with ideas or offers. That's where I wanted to be back then. That was my ideal situation. Now I'm working on a long book and sometimes I can't take all these offers. I can't do all those things that are really tempting.

SPURGEON: That is a change.

SACCO: It's a huge change. You look at what your peers are doing, also, and it just gives you hope. You see the sorts of books that are coming out, and the impact they're having, and the fact they're getting reviewed, and you see the fact that the

New York Times Magazine is running comics pages, and boy there's a big change.

SPURGEON: I recall that at one point you moved to New York to better pursue professional opportunities.

SACCO: That's it. At the end of the Gorazde book, I was about to give up, and I thought what I'll do is move to New York and I'll make the Last Stand. Even though New York is a difficult place to get by, I thought, "Here's the center of the publishing world. Maybe that's the right place to be." Let's see if that works. It sort of worked in its way. The Gorazde book came out and it was well-reviewed and those things seem to matter if they're reviewed in big mainstream publications. I did something for

Time. I was closer to a group of people who made me feel like I was doing the right thing. It helped. It was a shot in the arm that way.

SPURGEON: One of the things I find intriguing in the back material of the new Palestine

book was that balance you found between inserting yourself in the narrative and keeping yourself at a remove. I don't know if that was calculated or if it was something that you just felt your way through. I was also wondering how that element has changed for you since then.

SACCO: I think I felt my way through that. If someone really wanted to look at where that all comes from, I think it comes from the tone I achieve in

Yahoo #5. No one's ever asked me that question, so I've never really answered it.

Yahoo #5 is called "How I Loved the War" and takes place in Berlin. There's a tone I had, sort of a cynical, skeptical tone that I had that carried over. The next project I did as far as going somewhere was

Palestine. I went to Palestine and then came back and did

Yahoo #6. But really the tone of

Yahoo #5 carried over into how I did

Palestine. It wasn't something where I'm sitting back and thinking, "Oh, I'll do it in this way." It was a very organic process of writing. That's how I felt. That's how I wrote it. If I can say anything about

Palestine, it's that it's really organic.

SPURGEON: That's a wider journalism question, too, that pops up in everything from embedded journalism to Oprah standing near a crime scene and weeping on camera. It seems to be about how much of yourself is smart to put in there, how much will work.

SPURGEON: That's a wider journalism question, too, that pops up in everything from embedded journalism to Oprah standing near a crime scene and weeping on camera. It seems to be about how much of yourself is smart to put in there, how much will work.

SACCO: It wasn't the only thing I was doing, but I was doing autobiography in the

Yahoo series, like a lot of cartoonists were doing and are still doing. So when I was thinking, "I'm going to go to the Middle East," I thought of it in terms of maybe there will be some elements of journalism in this, I'll probably talk to people and all that, but it seemed almost second nature to think of it as a personal travelogue without thinking of the consequences of that. I came out of a milieu. I came out of autobiographical comics. People like

Chester Brown,

Harvey Pekar,

Robert Crumb. There were just cartoonists doing that, so you did [laughs] in a way. It was part of what people did. It seemed very second nature-ish to go and write about my experiences.

Now as far as how to balance that when you're actually drawing it, how much to leave yourself in or out of it, that's just an artistic consideration. For me, I realized Palestine was so episodic. There isn't one driving story or plotline. It's just a series of episodes. The only thing connecting them is myself. Of course you take a part of yourself and you make it your character. I didn't include certain aspects of my personality that wouldn't be interesting or would have undercut the story. You have to be very sparing if you show yourself feeling emotion. That doesn't mean I wasn't feeling emotion when I was hearing these stories or seeing the things I was seeing. It's more important to emphasize the humorous parts of your personality in those situations instead of "I'm really broken up. I feel like I'm about to cry now." Let the reader cry. You don't have to cry for them. [laughs]

SPURGEON: You know, issue #6 of Yahoo was completely different than #5 in terms of tone and your presence in the story.

SACCO: I think I wrote that before I went to Palestine, and I was drawing it while I was in Palestine.

SPURGEON: Did your perception of how that worked in relation to how #5 worked have an impact on how you approached Palestine

?

SACCO: No. No. Not really. At that point, I wasn't sure how I was going to approach

Palestine. I thought I would just continue

Yahoo on some level, too. To me,

Yahoo was a means of experimenting, and sort of finding a voice, or shifting my voices, because I was never interested in having a set of characters that lived in a situation, that gets a bit too sit-commy for me. I'm not that kind of writer. Some people are good at that. I'm not. So if I continue

Yahoo I probably would have just shifted gears each issue somehow.

SPURGEON: You've talked about doing stories that aren't journalism, but is there a kind of journalism you want to practice you haven't practiced yet? Is there a kind of story that you haven't covered? Is there any impulse to say, follow Barack Obama around for a year or dissect economic policy?

SPURGEON: You've talked about doing stories that aren't journalism, but is there a kind of journalism you want to practice you haven't practiced yet? Is there a kind of story that you haven't covered? Is there any impulse to say, follow Barack Obama around for a year or dissect economic policy?

SACCO: The way it is now for me is that I choose what I'm interested in and then I'll approach someone. That's the only way I really look at things. The only time someone called me up and convinced me that this was a good story idea and I did it was a story that's not been released but it's been completed for about three years about

Chechen refugees. So many people contact you about things, and you think, "Okay, whatever." But this person was serious and wanted to put her money where her mouth was, basically, and send me somewhere. So I thought, "Why not?" So I did a crash course on it. And I got really pulled into it. But that's really the only time I've done a story that wasn't self-generated. All the Iraq stuff, it was a question of contacting my agent and saying, "Hey, I'm interested in going to Iraq. Do you think anyone is interested in printing a comics piece?" And a month later she talked to people and came up with a list. That's a positive way my life has changed. People take me seriously now.

This is the big difference: Back in the old days, you'd do a piece about Palestinians and people would say, "It's in comics form?" And that would seem ludicrous. And now it's like

because something is in comics form, they want it. They would almost rather have it in comics form. That's how comics has sort of changed now. Editors are searching for this sort of stuff. It's a big, big difference. I'm sure it's same for a number of people. The younger cartoonists who are starting out now probably have some paths cleared for them. But people like me, and I hate to say it, my generation of cartoonists, our paths were also cleared for us by certain people. Art Spiegelman. Even the underground people.

The Hernandez Brothers and

Peter Bagge, those people cleared a path. You always benefit from what others have done.

SPURGEON: I don't have any more questions as much as I'm just sort of happy for you; it sounds like you've found a rational and fruitful way of conducting a major part of your professional life.

SACCO: Well, thank you. I don't have that many complaints. I overwork myself, because it's hard to be in the same creative space for a long period of time. You kind of want to move ahead. You have a lot of ideas. But cartooning is labor intensive. Or let me say this clearly: it should be. [laughter]

*****

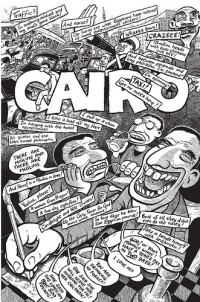

* cover to the new

Palestine: The Special Edition

* self-portrait

* page from new edition's back section, showing how a cover was colored

* two of the careening, wilder pages from Sacco's

Palestine era

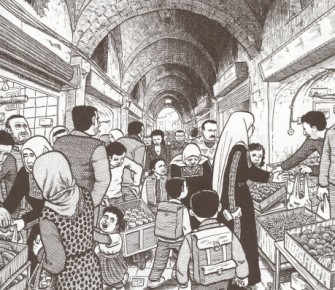

* from one of Sacco's freelance works

* photo from Sacco's signing, provided by Fantagraphics

* cover to an issue of the

Palestine comic book

* inset from

Safe Area: Gorazde I nicked from Dan Raeburn's article on Sacco

* another page from

Palestine

* a scene from

Palestine, I think

*****

*

Palestine: The Special Edition, Joe Sacco, Fantagraphics, hard cover, 320 pages, November 2007, 9781560978442 (ISBN13), $29.95.

*****

*****

*****