Home > CR Interviews

Home > CR Interviews A Short Interview With Tim Lane

posted December 23, 2008

A Short Interview With Tim Lane

posted December 23, 2008

*****

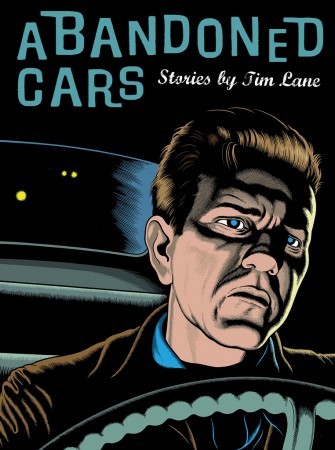

Abandoned Cars came out of nowhere for me. I has seen Tim Lane's work here and there, things like

the attractive cover he did for the latest Hotwire anthology. Nothing about those projects had prepared me to process what was between the covers of this new, handsome hardcover volume. Lane's work reminds me a lot of the post-underground generation that kind of fell to the wayside in the mid-1990s in favor of the humorists, fantasists and more strictly literary-minded and formalist crowd. If this were 1993, we'd be getting Lane's comics in a $2.95 black and white comic book four times a year and

Denny Eichhorn would be banging down his door for a chance to work with him in

Real Stuff. Lane's best comics are chilling, deeply melancholy character studies told with straight-forward prose and considerable visual panache.

His web site shows that he's a talented illustrator and restlessly creative cartoonist. I hope

Abandoned Cars isn't the last volume we see from Lane; indeed, he has two more volumes planned in the same vein. I enjoyed my brief contact with him in the course of preparing this interview, and thank him for his time.

*****

TOM SPURGEON: When I was researching for this interview I looked at your web site and unless I'm mistaken, most of what you've put up you've put up in the last several weeks. What caused you to go on-line in such a big way so recently?

TIM LANE: I think what you're referring to is the weblog,

jackienoname.wordpress.com.

SPURGEON: I am. Sorry. Is there another web presence somewhere?

LANE: My website,

jackienoname.com, has been up for a long time -- so long, in fact, that it hasn't been updated for a couple of years. My website guy moved to Thailand, and since I don't know anything about website construction, the jackienoname.com site came to a halt after that. I recently put up the weblog in order to display some of my "non-commercial art" related work, such as

Abandoned Cars. The jackienoname.com site is pretty much dedicated to illustration work I've done for clients.

.jpg) SPURGEON: Your book reminds me a lot of a certain kind of post-underground comic that you really don't see right now. Can you talk about your comics and illustration influences, who you find interesting and who might directly inform you work as it exists today?

SPURGEON: Your book reminds me a lot of a certain kind of post-underground comic that you really don't see right now. Can you talk about your comics and illustration influences, who you find interesting and who might directly inform you work as it exists today?

LANE: I think the biggest, earliest, and most sustaining influence on my work, in terms of comics, is

Will Eisner -- specifically

The Spirit. When I was growing up, during the mid to late 1980s,

Kitchen Sink Press was reprinting all of those great

Spirit comics from the 1940s, and I couldn't get enough of them. I'm a fan of his graphic novels, too, but, for me, it was

The Spirit that really resonated, got me interested in comics. I still refer to them, especially the ones created during the late 1940s, where the dynamic contrasts of black & white in his ink work, the shifting perspectives, make it very evident that Eisner was influenced by

film noir. Eisner's collected

Spirit material offers some of the greatest examples of everything from story pacing, page design and panel arrangement, etc, that I can think of -- everything about that period of his work seems innovative. And very fun. His splash pages from that era are incredible, too -- they just suck you right into the story.

Also reprinted in the '80s were the old pre-comics code

EC Suspenstories. That material really had an impact on me, too. The work of

Johnny Craig was, and still is, a big influence on me. But also

Al Feldstein,

Jack Cole,

Jack Kamen,

Wally Wood. Those

Crime/

Shock Suspenstories have the same kind of charm and appeal that old radio dramas from the '40s and '50s have -- radio dramas like

Suspense,

Inner Sanctum,

Escape. And I think some of those pre-comics code tales are gruesome, even by today's standards.

.jpg)

I really love those old

Dick Tracy newspaper dailies. I love the surreal meandering nature those stories can sometimes have about them. The oddness of the stories. In certain cases, you get the sense that

Chester Gould wasn't exactly sure what was going to happen in the next episode, and I really love that about them. I might be wrong about that -- perhaps he had the structure of each story nailed down long before he put pencil to the page. But there's a real lively fluidity to those stories, filled with the absurd. Those characters: The Brow, Pruneface, Shakey... every time I look at Shakey, for instance, I'm amazed by the simplicity and originality of Gould's artistic choices, the way he chose to depict a human face.

The underground comics of the '60s have had less of an impact on me, although I really appreciate the work of

Robert Crumb and

Spain Rodriguez. I've had a harder time tracking down compilations of Spain's work, and that's been very frustrating -- if you know of any, please let me know. I'd love to get my hands on them.

I've learned a great deal about overall page design and unique panel arrangements by looking at the comics of Glenn Head, especially his recent work. You can look at some of those pages for hours; they're really dazzling and absurd, but beneath the apparent craziness are some incredibly disciplined choices.

Recently I've gotten to be a big fan of

Kim Deitch. I love his writing style, especially

Alias, the Cat. I love how he plays the reader -- balances between believability and hogwash. He tells a yarn in what I think of as the old fashion Irish way. My Irish grandmother used to tell stories like that, a talent passed down to my father. The kind of story that leaves you wondering if the story is true or not, then reveals itself in the end. That's skill, and it takes real talent to keep your audience guessing -- "paddling in the water," so to speak. Deitch does that, and he's extremely good at it -- I'm thinking particularly of chapter two of

Alias. I love the multi-layered aspect of his stories, too: their depth and texture. Like with the first chapter of

Alias: a guy is telling a story about guy telling a story about a guy who told a story.

Charles Burns has been very influential, even pivotal. I'm constantly impressed with the precision of his imagery, his line work. It almost doesn't look like it was drawn by a human being, but a machine instead. It's incredible. That style works for him so well, but for myself, I'm glad I couldn't do that; I like there to be evidence of the human hand, the person who rendered the drawing. It's important -- even integral -- to the kind of stories I'm interested in writing.

Other comic artists I like are

Daniel Clowes,

Adrian Tomine,

Joe Sacco,

Seth,

Joe Matt,

Chris Ware. I've learned a lot from all those guys. I continue to learn a lot from all those guys!

David Mazzuchelli has also been a big influence. Again, growing up, I loved the

Batman series he did with

Frank Miller --

Batman, Year One. Later, he illustrated the graphic adaptation

Paul Auster's City of Glass, and that had an impact on me, too, but of a different kind.

Geof Darrow left a big impression on me, too... but I think I'm getting a little too long-winded here.

.jpg) SPURGEON: To shift gears a bit, am I to understand that you went through a period of wandering around and living in different places in America, maybe even having some of the experiences that later worked their way into this collection? What caused you to set out to these different places? What put you finally in St Louis?

SPURGEON: To shift gears a bit, am I to understand that you went through a period of wandering around and living in different places in America, maybe even having some of the experiences that later worked their way into this collection? What caused you to set out to these different places? What put you finally in St Louis?

LANE: Yes. Before I moved to St Louis a couple of years ago, I moved around a lot. Throughout my twenties, especially. And I traveled by land as much as possible -- buses, trains, cars. The landscape is an important element to the character of every part of the world, I suppose, but I think it's especially true in America. It's been important for me to see the way the landscape changes as you move from one part of the country to another. On a plane, you don't get that -- the dramatic changes in the land, the distances between places. Also, you meet people on trains and buses. You're with them for a long time. People start talking. Particularly on trains.

My experience has been that people who take Amtrak are mostly travelers who want to see the country, want to talk to people -- that's why they're doing it. Or maybe I just keep running into the people who are like that. I once spent a couple of days traveling from Oakland to Minneapolis with a guy who'd written a country song that sold to a well-known musician. He was living on the money he made, traveling around the country. I never saw him again, but for a couple days, we were traveling friends. Those are the kind of people you meet, and you learn a lot from them. Most of the characters in

Abandoned Cars are directly related to people I've known -- some combination between real and imagined people. The accuracy to their depictions varies somewhat. I've always been a collector of conversations. Living in different places is helpful in collecting a huge arsenal of potential material. But it isolates you, too. You're always on the outside looking in.

One of the main reasons I moved to St Louis was to work on comics more seriously. Before that, I was living in New York City, and was constantly working freelance illustration jobs just in order to keep my head above water. I really loved all that -- the illustration business -- but illustration has always been for me a means to an end. I knew if I wanted to get anything else done, I'd have to go somewhere else. I had lived briefly in St Louis once before, and knew of this neighborhood called

Soulard. It seemed the perfect place for me to live while I worked on comics -- at only a quarter the price I was paying in rent at my last apartment in New York, which was in

Crown Heights, Brooklyn -- not so great a neighborhood, at the time.

SPURGEON: I hear different things about St Louis as a city for artists. There are certainly some talented younger cartoonists that live there, and I hear that it's one of those towns that offers some of the amenities of a city without some of the over-gentrified high rents and insular scenes that other cities may have. What is it like for you to live there as an artist?

SPURGEON: I hear different things about St Louis as a city for artists. There are certainly some talented younger cartoonists that live there, and I hear that it's one of those towns that offers some of the amenities of a city without some of the over-gentrified high rents and insular scenes that other cities may have. What is it like for you to live there as an artist?

LANE: St Louis is a great old American city. You still have in St Louis great, gritty vestiges of the American past. It's also a city deeply rooted in American mythology.

Stagger Lee shot Billy Lyons here.

Frankie shot Johnny here. And you can see

Chuck Berry perform nearly every month at a bar/restaurant called

Blueberry Hill. To me, that's an incredible thing to experience hearing live, at a small venue, that unique guitar sound, which is practically as familiar as your own mother's voice. If you're into the blues, rhythm & blues, soul, etc, St Louis is a great city to live in. There's a stretch on Broadway -- downtown St Louis -- where, at night, out on the street, you can hear the best lives blues or rhythm & blues coming from three different bars simultaneously, while freight trains roll toward the Mississippi on the railroad bridges overhead. Not everybody would think of that as attractive, but I do. The only bad thing about St Louis is the summer's stifling heat and humidity. I grew up in Minnesota; the heat is brutal if you're from the north.

SPURGEON: You mention that you went through a period where you were very serious about your art and then that you wanted to get back into comics as a reaction to what was perhaps a specific kind of young man's feelings toward making art. Is that fair? What finally set you on the path to doing comics?

LANE: I think everyone with a creative inclination goes through a period, usually just after college, of discerning -- or having to discern -- the nature and uniqueness of their creative voice. It's one thing to exercise that inclination in the relatively safe environment of a college campus, but very much another thing when you're out their on your own, facing the pressures of daily life. And it's at this point when your idealism has to stand up to practical realities, as well.

Paul Auster writes well of this in his book

Hand to Mouth. He writes about how -- and I'm paraphrasing -- between his late twenties and early thirties, everything he touched turned to ruin. I love the way he phrases that. He goes on to talk about the anxieties of trying to reconcile wanting to communicate as an artist against the enormous pressures of practical living. For myself, that process involved coming back to comics -- or coming back to the things that first inspired me to communicate creatively. The important intuitive things that existed before pretensions had the chance to develop.

SPURGEON: Your work will no doubt remind people of a lot of mid-century authors: John Fante perhaps, and maybe some pulp writers -- your back cover text mentions Jim Thompson. Are there writers that you feel are an influence on your work? Are there specific difficulties in working a prose influence into comics?

SPURGEON: Your work will no doubt remind people of a lot of mid-century authors: John Fante perhaps, and maybe some pulp writers -- your back cover text mentions Jim Thompson. Are there writers that you feel are an influence on your work? Are there specific difficulties in working a prose influence into comics?

LANE: The pulp writers comparison in the PR material for

Abandoned Cars wasn't made by me. I've read Jim Thompson, but haven't read

David Goodis. I've only read one book by John Fante, and I don't remember much of it. A long time ago, I went through a phase of reading that kind of fiction:

Raymond Chandler,

Dashiell Hammett,

Mickey Spillane,

James M. Cain. I think it's great, but I wouldn't say it's had a huge influence on me, in terms of writing style. That comparison surprises me; I don't really see it. Writers, though, have made more of an impression on my life than anything else. I mention that -- perhaps too much -- in the first part of "Spirit."

Ernest Hemingway,

Jack Kerouac,

Thomas Wolfe,

Henry Miller... those guys really helped shaped my life in every way -- and it was largely because of them that I began traveling and, of course, writing.

Jack Kerouac stands out as the biggest influence when I was in and just out of college. His writing doesn't affect me like it once did. He's definitely a very young man's writer. But whatever one thinks of his writing, in terms of technique and style, he created a world so vivid you can touch it. I could go on forever about that stuff -- with all of the writers I mentioned. I won't bore you with it too much more. But the older I get, the more surprising it is to me that a guy like Kerouac ever even existed. He really represents to me the ideal of an artist -- his dedication to his craft, his ability to so clearly describe his vision, his experimentation, on and on.

In terms of the writers most influential to the writing in

Abandoned Cars, I'd include

Raymond Carver, the short stories of

Denis Johnson, Hemingway,

Nelson Algren. I'm really into learning how to craft beautiful, tight graphic short stories. Adrian Tomine is excellent at the graphic short story, in my opinion. I really admire his work. I've got a lot to learn, but am very excited about that process.

Which leads to your question about the difficulties in working a prose influence into comics. All of the stories in

Abandoned Cars began as literary short stories -- written out in prose form. I always planned on them being comics, but it was more natural for me to write them out in prose form first. It's taken a lot of pages to realize that that doesn't always work. Most of these stories were also very loosely constructed -- in some cases, I wasn't sure how they would end, but I'd be working on inking the first pages already anyway. The balance of text and image needs to be equal, overall, in comics. The work in

Abandoned Cars doesn't always express that. Those are some of the things I'm trying to learn how to do better.

SPURGEON: A few of your more effective works in

SPURGEON: A few of your more effective works in Abandoned Cars

are essentially character studies as much as they are narratives that detail an incident. What draws you to using comics in that way, what do you hope to achieve in taking that kind of a snapshot of someone, as in "To Be Happy" or "The Drive Home"?

LANE: That question relates to another influence on

Abandoned Cars:

an album by Bruce Springsteen called Nebraska. It's a very stripped-down acoustic album -- he apparently recorded it on an 8-track in his living room -- filled with, in essence, short stories that, when strung together, make up a bigger story -- or suggest a theme about American life. Each one of the songs speaks in the language of the characters. Springsteen is a great storyteller, and he paints with a broad brush.

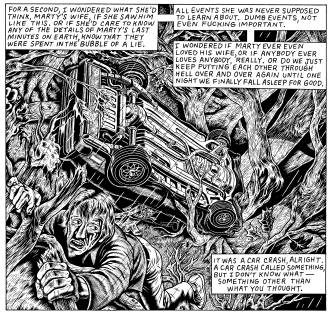

In the two stories you mentioned -- those stories about John -- as in many of the stories, I wanted to capture the language of the character and let them tell their own stories. With John, I wanted him to seem like he really didn't know what went wrong, why his marriage ended, but in his narration he inadvertently tells us what went wrong. We know why things didn't work out (or at least we have a pretty good idea), even though he -- at this point in his life -- doesn't. That's one of the things about just talking to people that's interesting: How much they reveal about themselves without intending to. Another thing about a character snapshot is that it allows the reader to draw his or her own conclusions. In a sense, I, as the writer, am not there. It's just John talking. But he's describing in his casual way incidents in his life that were critical.

SPURGEON: Some of your most compelling pages bring the reader's eye back away from the character to capture an element of their surroundings; is that just a matter of varying the visual in order to keep a page interesting, or are there thematic concern in how you frame an individual panel.

LANE: It's both. In the more recently done stories, my intention was to create a sense of hugeness to the landscape -- or, to a greater extent, the "Great American Mythological Drama," which is the theme binding all of these stories together -- by juxtaposing these smaller, more individual, ordinary narratives against the bigger things surrounding them. My hope is that it gives the sense that these characters are lost in a kind of enormous landscape – both a figurative and literal landscape... that the angles create a sense of tension and anxiety, like in

film noir movies.

I've read that early American pioneers spoke of the "sublime" when they spoke of the American wilderness. By that, they meant they were struck by its awesome beauty, but they were terrified, as well. Try to imagine how frightening the Alleghenies must've been, if you had no frame of reference. What lay beyond was a complete mystery. I'd be terrified, too. I think that awesomeness still exists today, only in different ways. In an American story, I believe Nature is a character.

SPURGEON: You wrote a fascinating essay about your Stagger Lee strip in which you talk about other cartoonists' attempts to work with that legend and suggest that you're all part of the rich tapestry of interpretation and meaning that surrounds that particularly folk story. One thing I found interesting was that you talked that at first you were going to work with the legend in terms of an old-time newspaper format, but the resulting work didn't have very much of that flavor at all. How in this case did subject matter dictate what you did with the material?

SPURGEON: You wrote a fascinating essay about your Stagger Lee strip in which you talk about other cartoonists' attempts to work with that legend and suggest that you're all part of the rich tapestry of interpretation and meaning that surrounds that particularly folk story. One thing I found interesting was that you talked that at first you were going to work with the legend in terms of an old-time newspaper format, but the resulting work didn't have very much of that flavor at all. How in this case did subject matter dictate what you did with the material?

LANE: I guess I meant the old newspaper daily concept in very general terms. You're right, though: Now that you mention it, those Stagger Lee episodes don't look much like old

Dick Tracy strips, in terms of format. But the Stagger Lee story ran as a serial at first: It has that in common with the newspaper dailies, if nothing else. The weekly

You Are Here column had to work within a pre-established format -- you have to take what you can get, right? Old newspaper dailies were the idea behind the conceptual approach to the Stagger Lee story. Maybe that's where the similarity ends.

SPURGEON: Did you design the book? That has to be one of the more handsome debut works I've seen.

LANE: Thank you! I really appreciate that. Or are you making fun of me?

SPURGEON: No! [laughs]

.

LANE: Yes, I designed

Abandoned Cars -- Fantagraphics was great about letting me do what I wanted. They were great about everything. I had very specific ideas about how the book should look, and how it should be paced -- they really seemed to appreciate that. The main "fictional" portion of the book is sandwiched by the young and old portraits of

Marlon Brando. They are the book ends. I just wish I could draw portraits better; I don't know if people are recognizing Brando. It's an important element to the book, that recognition.

SPURGEON: Did you assemble the work that appeared in

SPURGEON: Did you assemble the work that appeared in Abandoned Cars

? Was there anything to going back over so much work and putting it together in book form? How did you feel about the finished product?

LANE: That's a tough question to answer because there are so many elements to consider, and I've only had my own final copy for a short time. I'm happy with the finished product overall. And, yes, I assembled all of the work. Those stories were always meant to be together.

I think the quality of the work, from story to story, definitely indic ates the passage of time -- or more appropriately, the development of skill over the passage of time. These stories span about six years. The earliest story is "Ghost Road," the last was "Spirit, Part 3." The story of "Ghost Road" makes me wince a little. But thematically it fits in very significantly. So, although I'm not thrilled with its writing, I believe it serves its purpose well in the greater context of the book, however cumbersomely -- and I'm very glad I could include a fabrication of

Art Bell's Coast to Coast coming from the radio.

Overall, I think

Abandoned Cars is a fairly good start. For all of its faults, I can look at it as an accurate representation of myself, artistically and as a human being, and that means a great deal to me. Yeah, I'm pretty happy with it. But I'm still a long ways from being as good as I want to be.

SPURGEON: What's next for you, Tim?

SPURGEON: What's next for you, Tim?

LANE: Abandoned Cars is the first book of graphic short stories in a series of three -- the next two are tentatively titled

Folktales and

The Believers. There were lots of stories in varying stages of development that didn't get into

Abandoned Cars, which are all connected by the same umbrella theme. Mostly these will all be stories about new characters, but ones already introduced in

Abandoned Cars -- such as John and the Manic Depressive from Another Planet -- will return, sometimes as background characters, sometimes as central characters, at various stages in their lives -- and not necessarily chronologically ordered. Also, a few who were background characters in

Abandoned Cars will appear as central characters in the next books. I'm working on those stories now.

I've been working on the story for a separate graphic novel, as well -- unrelated to the three books of short stories. Beyond that, I'm trying to work out a story called

Belligerent Piano -- a story I've been working on, on and off, for a long time -- as a weekly strip, in the style of

Dick Tracy or

Steve Canyon.

Dan Nadel recently put out a book called

Art Out of Time. In it are some incredible and weird old daily strips. My favorite is

Dauntless Durham of the USA. Even it's title makes you smile and wonder "who the hell is that?!" Although you need a magnifying glass to read it -- sort of fun in itself! That stuff sort of inspired me to try a weekly strip. I'm publishing that on my weblog. But it takes a back seat to these other projects.

I'd really like to keep producing material for these next books, and other material that isn't meant to go anywhere else, in a regular pamphlet -- or what used to be called a comic book (to me, it doesn't feel comfortable calling them "pamphlets"). That's what my comic book

Happy Hour in America was supposed to be about.

Happy Hour was self-published, and distributed by a few distributors (Diamond, FM International, Last Gasp, and Cold Cut -- if I remember right -- but nobody seems to have ever heard of it. I really suck at self-promotion, so I'm not a good candidate for publishing my own stuff. But it would be great to have that regular outlet. I myself love that stuff. With Daniel Clowes'

Eightball, although he might be working on installments of a graphic novel -- things that will eventually be published as a graphic novel -- you still get things in it that are unique to that particular issue of

Eightball. Also, it seems to me that comic books are an important part of the tradition of comics. I guess people aren't buying comic book pamphlets anymore. It would be a shame to watch that die because they don't sell as well as they used to. Some things should be kept alive, just because.

*****

Abandoned Cars, Tim Lane, Fantagraphics Books, Hardcover, 128 pages, 1560979186 (ISBN10), 9781560979180 (ISBN13), September 2008, $22.95.

*****

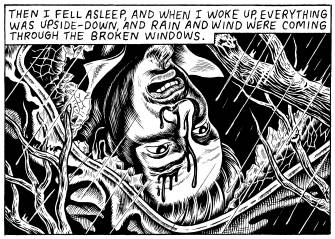

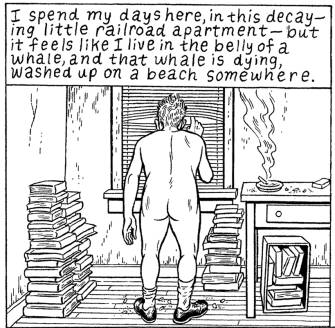

all images from Abandoned Cars

*****

*****

*****