Home > CR Interviews

Home > CR Interviews A Short Interview With David Malki

posted December 23, 2008

A Short Interview With David Malki

posted December 23, 2008

*****

I wasn't aware of

David Malki until several

CR readers suggest I track his on-line comic

Wondermark as part of my ongoing efforts to track down some of the best works in that realm of comics-making. I enjoyed the strip, and came away from

the webcartoonists panel at

HeroesCon in June impressed with the articulate and forthright way the cartoonist and film editor engaged with the issues of the day. A book of Malki's material from

Dark Horse's on-line comics initiative called

Wondermark: Beards Of Our Fathers hit bookshelves this month, making Malki part of the latest publication trend to hit webcomics. I suspect it and Malki will do very well in the months and years ahead.

*****

TOM SPURGEON: David, I'm not really familiar with your background at all. Is there a short standing-around-at-a-party-chatting biography you can give me as to where you came from and how you ended up in LA doing the comic? In particular, were you ever an avid comics reader? Can you outline in rough terms your experience with comics?

DAVID MALKI: I was born and raised here in Southern California, and went to college in Orange County (bachelor's in film production). After one gets a bachelor's in film production in Orange County, one usually moves to L.A. and tries to get an entry-level job in the film industry, which is what I did.

But I was a comics fan, too -- in fact, I applied for an internship at

Image Central back when they were headquartered in Anaheim. (They offered me the position, but by the time they called I was already interning at

New Line Cinema.) I'd read comic books since the boom of the early '90s, mainly godawful Image stuff, but enough gems that the habit sustained itself through most of college until I realized I had nowhere to put all these pamphlets. So that died until I got a job down the street from a comics shop and started getting into trades and indies.

Anymore, I read very very few comic books, and none regularly -- just don't have the shelf space or the disposable income. And if anyone wants to make me an offer on six longboxes of pamphlets from about '93-'01, I'll give 'em a killer deal.

But I'd

always read comic strips in the newspaper. I read every single strip in the paper, even the dumb ones. I never skipped any. For my entire childhood, I never had any idea what in the world was happening in

Rex Morgan, M.D., but I always read it whenever my parents bought a newspaper. My parents had

old Pogo books (which I, again, didn't always understand, but devoured) and '60s-era

Peanuts paperbacks, which I absolutely loved. My mom still gives

Calvin & Hobbes collections to her grandkids as gifts -- she was an early influence. But I also recall she once wrote to our local newspaper complaining that

The Far Side hadn't been funny lately. One of those people.

The point being that comic strips were far more formative than comic books. Looking at both industries today, from the perspective of an adult in their midst, I'm utterly baffled that the two media even share a common term -- "comics." I don't think they could be more different.

SPURGEON: Can you talk about some of the major differences you see? Because that's a classic take on comics that's kind of swung in the other direction the last ten years or so, towards their being much the same.

SPURGEON: Can you talk about some of the major differences you see? Because that's a classic take on comics that's kind of swung in the other direction the last ten years or so, towards their being much the same.

MALKI: I think they used to be more closely related than they are today. Comic books began as collections of strips, didn't they? And in newspapers you'd have the old full-page strips like

Little Nemo or

Dreams of the Rarebit Fiend which were these gorgeous illustrative works, and later as the funny pages shrank you'd still see

Dick Tracy and

Steve Canyon which were serialized adventure stories told four panels at a time. These were comic strips that read like comic books, or comic-book-type stories told as comic strips. There used to be a lot of crossover between the formats, in terms of the types of stories you could tell and even the talents and properties involved. I just saw a thing on

Journalista about a

Beetle Bailey comic book from 1953, with full-on comic-book style

Beetle Bailey stories.

You don't see that today.

Bill Amend and

Stephan Pastis aren't drawing comic books. And it's because of

Peanuts --

Schulz took the tiny scrap of real estate on offer in a newspaper and started to tell tiny little funny stories with it. And, notwithstanding the continued existence of strips like the soap operas and

the completely bizarre newspaper version of Spider-Man (none of which, I would argue, work as comic strips), that's pretty much what we have today. The comic strip format today is a joke delivery medium, or in some cases a story-made-of-bite-sized-jokes delivery medium.

Meanwhile, comic books decades ago spun that adventure-serial tradition into longer and more complex stories about superheroes, and later more literary works. Like Schulz taking advantage of his tiny scrap of newsprint, comic books took advantage of their full-sized multi-page format to tell bigger and more ambitious stories. Basically, we had sibling formats that grew up into very different adults -- sharing a family resemblance in their visual vernacular of panels and word balloons, but content-wise no more similar than poetry and novels, or pop songs and opera. They're two different types of storytelling that just happen to share a common language.

The reason any of that's important is because the audiences for the two formats are now completely different. People today, at least up until the current generation, have grown up reading funny comic strips in newspapers and are familiar with that form. Everyone likes to read a little bite-sized comic strip because it's quick and they expect a joke. A comic book has a lot more hurdles in front of it -- the length, the complexity (wander your local comics shop for ten minutes and tell me if you can find one pamphlet that a totally new reader could pick up and fully comprehend), and not least, the nerdy culture that's grown around it all. So few people even read for pleasure that asking people in general to read comic books is doubly difficult. But anyone'll read one comic strip, and if they laugh, maybe they'll read another, and so on. I think, in general, humor comic strips will always attract larger audiences than long-form comic books of any genre.

The differences between these formats (as well as new and hybrid formats) and how they appeal to different types of audiences are, I think, important components missing from all the talk about how to make money at webcomics.

United Feature Syndicate and

Marvel Entertainment don't share a business model, so why would anybody think that the many different types of webcomics do or should?

SPURGEON: How surprising is it to you and the people who know you that you're doing what you're doing now?

MALKI: It's not at all. I think one measure of doing something fun with your life is whether you're still doing the things you came up with on your own as a kid. I used to trace Charlie Brown and Garfield and Calvin and make my own versions. The influence of the aforementioned Image books led to oodles of ill-fated home-grown comic books, but strips are what stuck. I got two pages drawn of my elaborate fantasy epic, maybe nine of my sci-fi horror book, but I finished something like 125 episodes of my parody

Batman strip

Bic Man starring the ink-blob mascot from Bic pens.

SPURGEON: Although I think that perhaps you just quit your formal day job, I noticed that you're a film editor in addition to doing

SPURGEON: Although I think that perhaps you just quit your formal day job, I noticed that you're a film editor in addition to doing Wondermark

. Can you talk about how that work might have had an effect on your comics? For one thing, I have to imagine it provided you familiarity with some of the tools you use in assembling the work. Is there a way of looking at comics that you think might make you different than someone without your specific professional background?

MALKI: I spent about five years working full-time in motion-picture advertising (as it's known), working on trailers and TV commercials for movies, until I started turning down that work to focus more on comics. Editing TV commercials is a lot different from editing student films -- for one, there's such thing as a time limit. 30-second TV commercials can't be 35 seconds long. So that practice taught me a lot about how to get your message across quickly and within boundaries. But I also learned that cutting jokes way down and messing up their rhythm to fit three of them in a commercial is a good way to make them not funny -- sometimes you need to leave some breathing room.

The first people I showed

Wondermark strips to were colleagues at the agency where I worked -- folks who weren't necessarily comics fans, and who prided themselves on being both creative and critical. It got me in the mode of writing for a varied, reasonably intelligent audience as early as possible.

As for the computer skills & such, I was familiar with Photoshop, etc. from fooling around with other projects long before I started the comic. But I certainly honed a lot of technical skills working in advertising.

SPURGEON: You told Shaenon Garrity that you started doing the work that became Wondermark

in part out of a fondness for the older illustrations that you use. That's not exactly a common interest, David -- can you talk about your interest in that kind of illustration? Did you approach those old magazines directly, or did you enter them through their appropriation into other media? How did that interest develop?

MALKI: I was a kid that could stare at the engravings on a dollar bill for an hour, just marveling at the craftsmanship that went into it. My "formal" art training -- private lessons with a group of friends for about four years -- emphasized the fundamentals of craft above stylization. Our teacher, a wonderful illustrator named John Arthur, would pull out

Wyeth and

Frazetta and

Rockwell and

Wrightson and

Michelangelo and hold them side-by-side with the

Liefelds that we would bring in to show him. So a classical appreciation of craft was an important element of my artistic education. (And a solid foundation in figurative anatomy is why I can't really cartoon worth a damn.)

I think my first encounter with Victorian illustration was through a Dover clip-art collection, which I would just marvel at. That's what I first used for the comic, but when I began to see the same characters crop up in other media -- after all, anyone can use the same clip-art -- I started researching where the illustrations came from, with the idea to make my work more unique through the use of images that others didn't have the same access to or familiarity with.

SPURGEON: One thing I think that's interesting in working with the illustration the way you do is that on the one hand the images are sometimes similar panel to panel, which indicates that people might process them visually very quickly, but at the same time the quality of the art is very involved. Do you find in writing for that kind of art that there are approaches or types of writing that work better than other kinds of writing? Do you write for the art?

SPURGEON: One thing I think that's interesting in working with the illustration the way you do is that on the one hand the images are sometimes similar panel to panel, which indicates that people might process them visually very quickly, but at the same time the quality of the art is very involved. Do you find in writing for that kind of art that there are approaches or types of writing that work better than other kinds of writing? Do you write for the art?

MALKI: Sometimes I write to the art -- "what is this bear saying to this man?" -- and sometimes have to make the art fit a preconceptualized joke; it's about 50/50.

And there are some tricks of writing that I think are unique to the way my type of comic works. For example, if you look at a very streamlined cartoon strip, usually every element is in there for a reason. If the cartoonist goes to the trouble of drawing a vase in the background, then you know the vase is going to come into play somehow. But in my strip, a vase in the background might reasonably be there for absolutely no reason. It might just be part of the engraving -- the reader doesn't assign it any special importance. So in a case where the vase

does come into play (

Wondermark #342), it hopefully surprises the reader.

The same can be said for any of my strips that involve a change from panel to panel. What "any element I took the time to draw" is to the the streamlined cartoonist, "change from panel to panel" is for me. It draws attention to itself, and if it's not relevant, it distracts. Knowing that helps inform how I structure each comic, and it's definitely a different approach from how a traditional cartoonist might work.

SPURGEON: On the webcomics panel at Heroes Con, you were one of the cartoonists that mentioned that your impulse to do this work preceded your wider interest in webcomics and what was out there? At the same time, I believe the first time I heard your name was in conjunction with the cartoonist Steve Hogan, and I assume you have friends in that part of the comics field. How did becoming a member of that community and your relationships with other cartoonists have an effect your work, or your feelings towards that work? Has it been helpful? Hurtful? A non-factor? Are there any dangers to be found in the camaraderie of arts communities?

MALKI: I think there's definitely a danger of getting too insular. An advantage that comic strips have over comic books (if the artist takes advantage of it) is the work is not necessarily limited to comic-book fans. People young and old, male and female, rich and poor, read comic strips, and the same can't be said for comic books, at least in this country. So (with the occasional exception) I try not to write specifically for comics fans, a trap that I think is easy to fall into when you hang around comics fans and read comics messageboards and inundate yourself with comics stuff. As far as writing the comic goes, I want to insulate it from the world of "comics" as much as possible.

But being a part of the comics community personally has been hugely beneficial. Participating in fan messageboards helped me publicize

Wondermark early on, and that grew into links from more popular webcomics, which helped me develop what's become a more self-sufficient audience. It's been great fun meeting and hanging out with other creative people whose work you respect and who're doing the same thing you're trying to do -- working and learning from each other, having nerdy conversations that nobody else cares about. The social component of conventions is absolutely my favorite part, and I really hope that rising travel costs don't ruin that part of the experience for me. And being involved socially has opened up a lot of business opportunities as well. It's the same as networking in any other field.

SPURGEON: One of the macro-stories about on-line comics is the growing ability for people to make money with the on-line material at its center. As someone on the inside, and even a beneficiary of some of these opportunities, can you talk a bit about how things have changed since you started? I get the sense that there's some perhaps slight trepidation on the part of some of you that have been around a while when you see folks approaching webcomics as a business opportunity first.

SPURGEON: One of the macro-stories about on-line comics is the growing ability for people to make money with the on-line material at its center. As someone on the inside, and even a beneficiary of some of these opportunities, can you talk a bit about how things have changed since you started? I get the sense that there's some perhaps slight trepidation on the part of some of you that have been around a while when you see folks approaching webcomics as a business opportunity first.

MALKI: I definitely didn't start Wondermark as a business. I don't fill my site with tons of ads, and I'm very sensitive to how often I ask my readers to buy some new product. I think in the webcomics business model there should be a balance between how much free entertainment you provide and how much you can ask readers to invest in your success, and my teeth grate when I see comics that haven't figured out that balance yet (or who willfully weigh down the wrong side).

I'm glad I didn't know anything about webcomics back when I started. If I knew how people were making a living at webcomics back when I started a webcomic, I would have been impatient for my piece. That's just the truth.

Everyone who writes a novel wants to sell as many as

J. K. Rowling; everyone who writes a screenplay wants to make a million dollars or win an Oscar. Now there's webcomics too. I'd rather it not be this way, but I think plenty of people look at

Randy Munroe and wonder why isn't it happening to them.

SPURGEON: You've worked in a variety of different ways with this material -- for instance, I access your work at your Wondermark url, but I also believe you've worked with one of Joey Manley's sites. Is there anything different about right now in terms of the opportunities provided work like yours that might not have been there two or three years ago? What excites or interests you about the current publishing landscape?

MALKI: I syndicate the comic to Manley's

Modern Tales as well as a few other websites, and that's just another way to reach new readers without any skin off my nose. I'm what you might call a "reluctant optimist" in terms of new platforms -- sort of a middle-adopter. I figure anything that I use myself is something that's reached a critical mass for a sufficient number of other people too. A few years ago that meant creating an RSS feed. Then it was Facebook, now Twitter. But I go through life perfectly contentedly without reading comics on my cell phone, so I'm not going to spend a lot of time working on some sort of alternate version of the comic for phones, for example.

People are so used to getting the content they want, how they want it, that I'm gonna make sure the comic is in places they can read it easily without barriers like a subscription wall or a clickthrough ad or putting only a link in the RSS. As long as I do that then I think I've done my job. If they

really want the comic on their iPod they're probably the kind of nerd that can figure it out on their own.

And there are certainly more opportunities now for content than ever before, with the disadvantage that it's harder to stand out from the crowd. That's always the problem in any medium, and it's not going to get any easier in the future. The secret now, as it's always been, is to do good work. The better your work, the less hard you'll have to work to get people to read it. I work reasonably hard, but

Nick Gurewitch has to beat people away with a stick.

I also think it's cool that we're at a place in time when cartoonists like

Dave Kellett and

Bill Barnes can print their own books, sell them to their fans, and make a living at it. The democratization of self-publishing may have made everyone with an ego think they're an author, but it's also made it possible for people like Dave who couldn't care less about publishing deals or getting into bookstores to provide his healthy-but-not-massive audience with a quality product that he makes an excellent profit from. Self-publishing lets you take all the risk and reap all the reward, so if you've got a website with a dedicated fanbase, hooray! The risk for you is much less than Aunt Elsie trying to sell her self-published romance novel out of her trunk. You've sidestepped what used to be the major pitfall for self-publishers, attracting an audience, because you built the audience before you made the book, and only made the book once they've told you they're hungry for it.

SPURGEON: Can you talk about how the Dark Horse deal developed? Were you brought in after they had worked with Nicholas Gurewitch or at the same time? With whom did you work at Dark Horse and how closely were you involved in terms of how the final product came out?

SPURGEON: Can you talk about how the Dark Horse deal developed? Were you brought in after they had worked with Nicholas Gurewitch or at the same time? With whom did you work at Dark Horse and how closely were you involved in terms of how the final product came out?

MALKI: I was at

SPX with

Nick when he premiered his Dark Horse book last fall, and told him how I'd been ready to do a new collection for a while but, after the process of self-publishing, I wanted to try and see if I could interest a publisher -- as a way to potentially reach an audience bigger than I could just through my website. I think Nick talked to his editor,

Dave Land, because Dave got in touch with me and we started that whole process of seeing if it'd be a good fit for them. Nick's book really opened a lot of eyes, I think, to the commercial potential of webcomics -- but I had to warn them, "This isn't going to sell quite as many copies. Let me just tell you that up front." Because Nick's comic is atypical as far as webcomics goes.

It was because I knew that the book would live or die on its content -- not my reputation or the popularity of the web strip, neither of which even approach PBF levels -- that I knew it had to be a book that would take your breath away in a bookstore even if you'd never heard of

Wondermark. So I was very picky about how it looked. We went through a lot of proofs. Having designed a couple books already, it was easy to say "Here's exactly what I want." And to their credit, they said, "Fabulous."

SPURGEON: I know that you printed some of your own work before -- how was this experience different? Has there been anything that's surprised you about working through a publisher like Dark Horse and the relationship you've developed there?

MALKI: They've been great. Dave Land said to me, early in the budgeting process, "Tell me what you want." And I said. "Uh, geez, well, I know this is pie-in-the-sky, but I'd like a cloth-bound hardcover with gold foil and glossy color pages. But seriously, I'd be happy with a black & white paperback." And Dave came back a week later and said "Good news! We're gonna do a cloth-bound hardcover with gold foil and glossy color pages." Having them behind it that way was incredible. I could never have afforded to do a color hardcover if I'd self-published.

And they let me do whatever I wanted with it. They didn't ask what was going in the book, which was great because I didn't even really know what it would look like until I sat down to design it. I don't know if that's a typical role for a publisher to play, but it's exactly the way I like to work.

SPURGEON: Having done the strip for a while, and compiling the work into a book which might have given you a chance to look at a bunch of the material with fresh eyes, how would you describe the kind of humor you're exploring in Wondermark? What do you find funny, and is that the same thing as the humor you're writing?

MALKI: Personally I love very dry humor, which I hope is on display in the book's packaging and design. I think tackling absurdity with an absolutely straight face is one of my strengths. The strip itself is a little more traditionally jokey, but I hope it never talks down to its audience. If I had to nutshell it, I'd say it's "absurd things happening to ridiculous people."

I think it's important in writing to stay true to what one finds interesting, and not try to pander for the sake of an audience. The people who're in tune with your sensibilities will stick around, and the ones who aren't, won't. That's perhaps one advantage of a webcomic over a print comic strip in a newspaper -- the only people who go to the trouble of visiting your site are the ones who want to. Over time, ideally, you end up cultivating an audience who'll follow you through variations, experimentations, etc. because they find the same things funny that you do.

SPURGEON: Do you feel constrained at all by Wondermark

?

MALKI: Sure, but I think constrictions are part of the fun. I think any form has its constrictions, or maybe should. It's nice to have a starting point for the days when you're staring an empty document. I think writing a gag strip has its own limitations and freedoms vs. a story strip, for example, and on balance isn't any easier or harder.

The moments when the constrictions are most frustrating are when I've written a joke that requires some particular element to work -- let's say, a teacher in a classroom -- and then I have to page through dozens of books looking for a picture of a teacher in a classroom. If I were to draw the strip, I could just draw whatever I want and wouldn't have that problem. Often I'll construct the necessary scene from component pieces, which involves a lot of hunting for an arm in some specific position, a face that looks like it could be the same person from the previous panel but looking another way, etc. Those moments are the most challenging, but if I do my job right, the end result looks perfectly authentic and the process isn't evident to the audience.

The advantage of working this way is the opportunity to create unexpected things in the milieu of Victorian engraving -- for example, a ninja on a unicycle (#238). Hopefully seeing that surprises the reader.

SPURGEON: A huge difference between on-line comics in strip form and newspaper comics is the amount and ease of the feedback you can receive on-line. Having a forum, or having readers able to e-mail you, what has that experience been like? Do you think it has an effect on the way you create, or the choices you make in how to present something?

SPURGEON: A huge difference between on-line comics in strip form and newspaper comics is the amount and ease of the feedback you can receive on-line. Having a forum, or having readers able to e-mail you, what has that experience been like? Do you think it has an effect on the way you create, or the choices you make in how to present something?

MALKI: Personally, I think it's great, but then in my experience, usually the people who bother to write are complimentary. I'm sure there are other artists who've had different experiences with audience feedback. I'm not really bothered by negative feedback, because as long as there's

somebody out there who gets what I'm doing, then I know I'm not crazy. It's just not some folks' cup of tea, and that's fine, because it is some other folks'.

Going back to the idea of writing in a way that's true to you, I think a corollary is that you attract the audience that you attract. If you're a jerk and you write a comic that's jerky, then you attract an audience of like-minded jerks and you shouldn't be surprised when the feedback you get is rude. If you're gregarious and friendly, and your comic reflects that, so will your fans. In my case, Wondermark tends to be a bit sarcastic, a little silly, more literate than some comics, and those are the kinds of emails I get.

But this is an area where I think someone starting a new webcomic might get tripped up. Again, I'm glad I did the comic for a few years in total obscurity. I'd already figured out my game and gotten into my groove by the time anybody started paying attention. If I'd had people emailing me after two weeks saying "this suxxxx" I don't know if it would have been quite as much fun. I don't know if I should tell newcomers not to pay attention to criticism, but they should probably at least hold off posting their work until they've got thirty or forty episodes under their belt, so when they receive the inevitable "this suxxxx" emails about episode #1, they're in a place to look back and think, "I agree! The stuff I'm doing now is so much better."

SPURGEON: One thing that's interesting about Beards

is the longer commentary pages, and the running commentary. Can you talk about those choices in deciding to present the work in that fashion?

MALKI: The running commentary with each strip is the mouse-over text from the website, sort of a bonus aside after the strip's punchline. That's one of the cool tools that the Web affords you, and I think we found a way to make it work in print. The longer commentary pages, and really a lot of the non-comic content in general, are a value-add for the folks who've already read all the comics online. I'm a firm believer in making sure my books have value unto themselves. I want them to be more than just printouts of stuff from the Web. I want to give the reader an extra experience -- in some cases, an experience they could only have in print.

And I think all that stuff helps put the book firmly on the "humor" shelf in the bookstore, rather than in "comics." That's the audience I'm trying to reach -- fans of humor, not necessarily just fans of comics.

SPURGEON: Have you ever received criticism in terms of using the art you do, from people that don't consider that an artistic endeavor on the same level as drawing the work yourself? I have to imagine that most people would recognize what you're doing as valid, but at the same time comics fans can be conservative and dismissive.

MALKI: Yeah, I've only ever heard that criticism from comics fans. I see comics fans arguing all the time about whether so-and-so is a product of laziness, or whether this-and-that deserves its success, or whether thus-and-such should even be called a comic at all.

On the one hand, I can understand the impulse -- our culture places a high premium on effort, and things that look difficult are always given more consideration than things that look easy. If there are two equally successful things, the one thats look hard will elicit a "Wow, that's amazing" response, and the one that look easy will elicit a derisive "People pay for that???" It's the root of our objection to plagiarism -- regardless of whether an article, say, reported the facts correctly, we don't want anyone to get away with claiming to do work they didn't do.

So having a comic strip that really obviously makes use of copy/paste might strike some people as being a shortcut, or a cheat for not being able to draw well. A lot of times those objections come from folks who've spent a lot of time learning how to draw, and they don't like someone seem to get away with not putting in the same effort.

I can't really speak to those objections, because those people and I are on totally different wavelengths. I used to feel like I had something to prove, like I had to make sure everyone knew how much work I put into the strip. I don't really feel that way anymore; I just try to make sure my work gets in front of as many people as possible, and hopefully some percentage of those folks will dig what I'm doing. The ones who don't, I don't need. Let them argue about it among themselves, if they want.

I don't know if it's endemic to comics, but people love trying to put things in boxes: this or that does or doesn't succeed as a comic for such-and-such reason. I really couldn't care less about that argument. I happen to call what I do a "comic strip" because it uses the vernacular of the form, and people are familiar with what that means. But under different circumstances I'd be just as happy to call it a "comedy website."

I don't care about making comics for the sake of comics. I'm trying to make funny things. They just happen to look like comics, most of the time.

SPURGEON: A couple of things you've said makes me think you're still looking for images, still looking for new characters. Is that true? What is the quality that presents itself that you think distinguishes that kind of art in a way that makes you want to work with it? Is it something that's inherent to the drawing? Do jokes suggest themselves right away?

MALKI: I've only ever repeated source illustrations grudgingly. (Or, in rare cases, when characters recur.) I'd rather each strip look totally new and unique. So I'm always trying to build my database of images, finding new characters, adding to the cast. Because the images are static, there's a real tendency (I think) for them to get old. Once you've seen a certain character, there's nothing novel about him or her the second or third time. So I definitely try to make each strip feature something new that I can present to the reader: "Hey, have you seen

this image? Pretty cool, huh?" That's something that works on a different level from the storytelling: simply being able to share the old images that I unearth with the world.

In some cases, a joke (or the rough shape of a joke) can suggest itself from an image very quickly. The Bob character from

comic #139 suggested his strip right away. That sort of fascinating character attracts me immediately -- when the image itself is just funny. Political cartoons from the era are a rich source of bizarre visuals, because they're full of symbolic imagery -- for example, the guy

in the last panel of #156 is actually, I believe,

Otto von Bismarck, and the thing in his hands used to be a zeppelin representing the pressing issues of contemporary Germany, before I stripped out the sneering face.

SPURGEON: Have you come to notice a difference in the quality of the illustrative art from say, German satirical magazines as opposed to English humor magazines? For instance, are there schools of work where imagery tends to be repeated with more frequency, become recurring drawings? Is the drawing simply different?

SPURGEON: Have you come to notice a difference in the quality of the illustrative art from say, German satirical magazines as opposed to English humor magazines? For instance, are there schools of work where imagery tends to be repeated with more frequency, become recurring drawings? Is the drawing simply different?

MALKI: I've definitely learned which types of magazines are most likely to have the sorts of illustrations that are most useful for my purposes. It's gotta be before 1890, which was when they figured out how to reproduce paintings and photographs, and the woodcuts start to disappear around then. English humor magazines tend to have sketchier art, and the stuff before about 1870 has very loose linework that doesn't read well in a comic. The images in

comic #402, for example, come from an old

Punch, and in the first panel I had to add a halftone to pop the guy away from the background. By contrast, literary magazines such as

Harper's and

Frank Leslie's tend to feature much more intricate engravings --

comic #414 uses an image from Leslie's, I believe. Some of the full-page engravings in these magazines are beautiful, but all the linework is totally lost when reduced to comic size, so the effect isn't as cool. I've used a few of them to make greeting cards, which I think is a better way to showcase that level of intricacy.

Harper's also features serialized fiction, which can be handy because sometimes you'll see the same characters in different poses over the course of the story.

Comic #304 was built that way. Harper's also features a lot of landscapes and buildings in their articles about travel or historical places ("the house where Joan of Arc lived at age 12," that sort of thing), which are great for backgrounds. And if you need a hat or a desk or a table or a vase, best to pop open the 1901 Sears-Roebuck catalog. You just get more familiar with it all over time, so depending on what sort of image you need, you know where to start looking.

SPURGEON: Do you a feel a kinship with people who have worked with this kind of material in the past, say Shane Simmons or Terry Gilliam's animated bumpers for the Monty Python show?

MALKI: I think it's cool that other people have appreciated this work in the same way that I do. People like to bring up

Max Ernst to me a lot, whose work I finally looked up after having never seen it. He was doing almost exactly what I do! His stuff is awesome, and I've even seen a few images I recognize among his work. Seeing his stuff is really inspiring. I'm not familiar with Shane Simmons, but I'm a big fan of Gilliam. And there are other people who've used Victorian clip-art to make comics or other things. But I still feel my work is different enough from any of these others that I'm able to feel out my own way.

SPURGEON: Do you have a sense of who might buy the book, and how that group might be different than the readers on-line? Who are your readers?

MALKI: I really hope that the book is neat-looking enough that we'll have a lot of browsers picking it up at the bookstore. In fact, I addressed the preface of the book specifically to those people. My fondest, fondest wish is for someone that has absolutely no idea what

Wondermark is to pick up the book and be enchanted by it.

When I'm at conventions, I hand out flyers containing a couple short comics to the people walking by. I do my best to hand them out indiscriminately, because I've learned that there's no way to tell -- the person you might think would be totally uninterested ends up walking away with one of everything you have for sale, and the ones you think are totally your kind of people just shrug and throw the flyer away. There is absolutely no pegging a demographic, and I love that. It means that the book's hopefully for anyone who goes to the trouble of browsing the humor aisle.

SPURGEON: What's next for you? Is Wondermark

something you'd like to continue for as long as you have an audience? Do you have ambitions elsewhere?

MALKI: I've always had ambitions running in a dozen directions at once. I finished a short film earlier this year, and I've been taking that to festivals all around the country and am working on a feature screenplay. In addition to

Wondermark comics and books, I have a

Wondermark greeting card line and have just published the second of my "Dispatches from Wondermark Manor" parody Victorian novels. I'd love to keep making comics as long as folks want to read them, but as I said before, I'm most interested in making things that people enjoy. If they look like comics, great, or if they take the form of something totally new, I'm all for that too.

*****

*

Wondermark: Beards of Our Forefather, David Malki, Dark Horse Comics, Hardcover, 96 page, 9781593079840, July 2008, $14.95.

*****

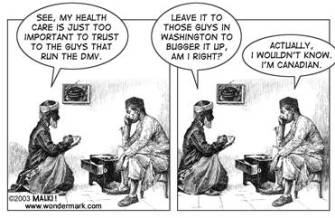

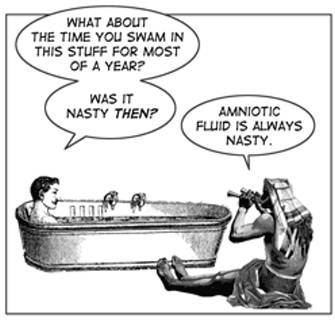

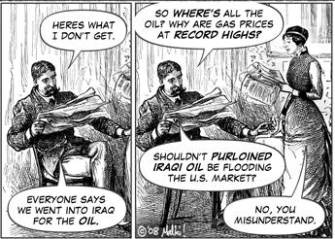

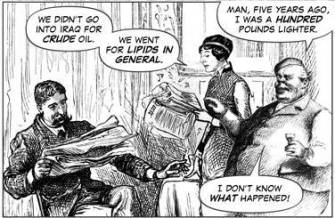

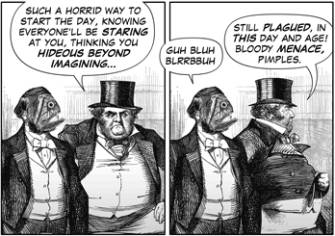

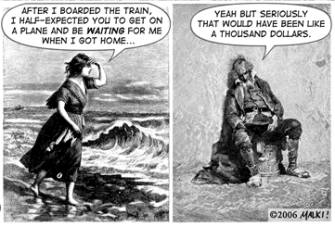

* all art from

Wondermark site; book cover for new collection up top.

*****

*****

*****