Home > CR Interviews

Home > CR Interviews A Short Interview With Gary Spencer Millidge

posted July 19, 2009

A Short Interview With Gary Spencer Millidge

posted July 19, 2009

*****

I don't know

Gary Spencer Millidge beyond his entertaining series of graphic novels

Strangehaven and as a friendly presence with whom I shake hands and exchange pleasantries at the occasional comics convention. Receiving his new book

Comic Book Design was a double-surprise, then, because I had no idea he was working on it and I thoroughly enjoyed the experience of reading it.

Millidge uses a broad definition of the word "design" to tackle just about every aspect of comics making in one way or another. He employs an aggressive number of examples to make sure that you get exposed to a wide variety of comics, particularly those from 1980-on. Some people may pay lip service to knowing and appreciating a wide variety of English-language comics; Millidge has put his catholic taste in such comics right on the page. Half the fun of

Comic Book Design is art directing the book in your head, figuring out which examples you'd use or emphasize and whether or not you agree with the choices made by Millidge and the

Ilex Press team. If I had this book to check out and read during high school study hall, I'd be on my 21st year working in comics rather than my 15th. I was grateful to read

Comic Book Design and to be afforded this chance to get to know Millidge better. For one thing, I wanted to ask when we were going to see

Strangehaven again. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: I was surprised to get your book, Comic Book Design

. I hadn't heard a lick about it. Can you talk as explicitly as possible as to how the deal came together?

GARY SPENCER MILLIDGE: I was a little surprised to get offered it, too, to be honest. Essentially, I had already written a couple of all-ages how-to-draw type books for a London publisher called

New Holland, and Tim Pilcher the commissioning editor at

Ilex Press (who I knew from his Vertigo UK days) asked me to write a "

blad" for a book on self-publishing comics.

As it turned out, that book didn't get picked up, but Tim asked me to write

Comic Book Design, which was an existing proposal at Ilex. So I had a meeting with them and agreed to do it.

SPURGEON: Does the book accurately reflect how you think about comics? Was there an element of this being your statement on comics? Have you always thought in terms of design with comics this way?

MILLIDGE: No, I haven't always thought about comics in terms of design, but gradually over the past few years I have begun to realize that my own creative process consists greatly of a methodical, design-like process, rather than a purely instinctive one.

Having said that, I think there's always more than one way to look at anything, and sometimes that just depends on what you mood is on any given day. Perhaps by analyzing the creative process of comics from a strictly design oriented viewpoint you might bring a fresh perspective to the subject.

So although it's not exactly my "statement" on comics, the book has given me plenty of scope to discuss every part of the comics creation process by analysing the very best examples of comic art that have been produced over the last hundred years or more.

SPURGEON: I think one thing that will really strike people about this book is the range of material and samples you reprint. Your copyrights page is this scary two-page spread of tiny type. What was the process like of getting all of these people to agree to let you discuss their work in this book. Were there any hassles along the way? Were there rights to anything that you wanted to run that you couldn't get?

MILLIDGE: Well I think in a book of this kind which includes commentary and analysis of generally a positive nature, it's fairly safe to work under the assumption that you'll get a positive response to any requests for permission. The exception to that I found was

DC Comics who for a number of reasons apparently guard their rights rather jealously.

I worked under the assumption that I wouldn't be able to use any DC stuff, which to be honest was a total pain in the ass. As it turned out, a tip from Joel Meadows suggested that we might be able to obtain permission to reproduce a small number of DC-owned properties in the book, and that turned out to be the case. Unfortunately as I couldn't be sure the selected DC pieces weren't going to get pulled at the last moment, there were very many examples and creators that I simply had to leave out.

There were also one or two creators that had personal issues -- either with me or people at the publishers, not sure which -- who didn't want their work featured in the book. We couldn't get permission for some

Frank Miller images as we simply couldn't contact him before the presses rolled. And only about a third of all the images I initially selected actually made it into the book, purely for space reasons.

SPURGEON: Does the range of material reflect your own conception of the comics art form and what's vital, or was there some plotting out in terms of "I should make sure this camp is reflected, and that this doesn't overpower this" and so on?

MILLIDGE: There were some suggestions from both Ilex Press and the US publishers of the book, Watson-Guptill, as well as the editorial team, that certain creators should be included. There was also an understandable desire that certain names should be incorporated from a marketing point of view. We compiled a fair-sized list in the end. But of course I wanted to reflect my own broad taste in the comic book field anyway, so it wasn't so much a matter of making sure that certain 'camps' were reflected, but making the most of the opportunity to demonstrate the huge variety of styles of comics that exist.

I think pretty much all the images were taken from my own personal collection and therefore the choices reflect my tastes and interests pretty accurately. If I made any concessions to include creators who may not have been on my own personal shortlist, then I think the book has turned out better for that.

SPURGEON: One thing that hit me when I was reading the book is how thoroughly you apply principles of design to aspects of the comic book. It's not just that there's a section on spine design -- although I'd love to hear you talk about how that came about -- but that you seem to see design issues in every single aspect of comics. Is that a fair assessment of where you're coming from? Are there are elements of making comics where you feel design plays almost no role?

MILLIDGE: I think design is a loose enough term that it can be applied in all kinds of ways, not just in the sense of "graphic design." The opening chapter on "character design" might have been stretching a point -- apart from the visual design of a character -- but I think it makes sense in the context of the book as a whole.

Likewise, there's a substantial section about storytelling in the book which might not immediately seem to be related to design. But in terms of laying out a page, so that each element is contributing to progressing the story in some way, by leading the eye, or by creating harmony and balance, ideally

should essentially be about storytelling.

The actual packaging of the book and its covers is what most people would probably think of as it's "design" -- and that is something that has always interested me. And in a book store environment, where most books are displayed spine out, the design of the spine itself may the only aspect of the book that can attract a potential purchaser, so its design is a very important aspect, no?

I think that applying graphic design principles to other aspects like lettering and coloring is also valid in the context of the book as a whole. It helps make the book more of a comprehensive reference for the student of the medium, or for the budding creator.

SPURGEON: Who did you perceive reading the book? Comics enthusiasts? General audiences? Burgeoning creators? I can see a case for multiple audiences including those three but I wonder if you had someone specific in mind, if only as the primary reader.

MILLIDGE: I don't think it's wise to try to second-guess your audience, and I think most writers would say that they're primarily writing for themselves. But I admit I do find it easier if I have one or two profiles of potential readers of the book in my head when writing. Particularly, my brother and his three sons are all very arty, and his eldest is a very successful animator (he was lead animator on the Oscar-nominated "

This Way Up"), but he's not particularly into comics

per se; I'm hoping he's the sort of person with a passing interest in comics that would pick up the book in a store and be intrigued by the possibilities of our humble art form.

I like to imagine that this book could cross over the commercial art and comic markets; designers with some interest in comics; comics readers who want to know more about the processes behind the creation of a book, with the intention of broadening the knowledge of the reader. Introducing

Seth to a

Spider-Man fan or pointing out the innovations of

Jim Steranko to a reader of

Persepolis. The juxtaposition of placing artists like

Bill Sienkiewicz and

James Kochalka together in this book is the sort of thing that made it such a fun thing to do.

SPURGEON: While your book is festooned with positive example of great designs, and it's easy to understand why that strategy is employed, I was wondering: do you seem comics in a critical fashion, perhaps some where they've failed to employ excellent design? And if so, in terms of books out there right now, what do you see as the primary area where bad design happens?

MILLIDGE: As a creator myself, I don't like to criticize fellow creators too much, especially not in print. I like to believe that by pointing out examples of good design makes good design self-evident, despite the fact that my experience tells me otherwise. There are lots of things I could point to and say how badly they're designed, but sometimes there are mitigating circumstances, so I don't like to be too harsh. Heaven knows that there are plenty of things of my own I could point to that are terrible in every way.

Compared to creating a new work of art, I think criticism is pretty easy. Criticism has its place of course, but good criticism is far rarer than good art; it's so liable to be skewed by personal tastes and prejudices.

I think also there are different ways in which you can judge good design. Is a good cover design one that sells the most copies? Or one that adheres to design rules and standards the most closely? Or perhaps the most aesthetically pleasing from a design point of view? Is a great design on a cover still a great design if no one can tell it's a comic?

It is interesting to analyze design in anything, trying to figure out why the designer made specific choices; whether they were intuitive or concious choices; or whether the design was undermined by a last minute editorial change or whatever.

At the very least, I hope it's just a visually spectacular, interesting book to have lying around on the proverbial coffee table.

SPURGEON: An idea you bring up a couple of times in your book is that many cartoonists will apply a principle you're discussing without thinking about it in quite that way, as just a natural extension of what they do. How much does this apply to yourself as a cartoonist. Looking at your past work, should we see this as a collection of rational choices to bring about a certain effect, or have you winged it at times, made choices out of an artistic impulse without giving these matters as much thought as one might think reading you hold forth in this book?

MILLIDGE: Well that's the luxury of being given the opportunity to write a book like this -- analyzing why great comics work and consciously applying that to your own work. Like most other things, the best way to learn is by doing it yourself. Reading this book won't make you a great cartoonist, but it might help analyze where you're going wrong, suggest areas of improvement and, most specifically, to inspire new ways of working.

Some of the opinions in the book were formulated while reading comics, some during the years I've spent creating comics, and more still while studying and researching for the book itself. Some of the principles discussed in the book are really for analysis only, and are universally self-apparent to any artist worth his salt. Perhaps other ideas are more obscure and open to discussion.

Applying the principles that I discuss in the book retroactively to my own work would help show up many of my own faults as a creator, I'm sure. I think sometimes you realize that you've not really ironed out all the problems with your layout, even as you're still working on it, but you have to just move onto the next page at some point.

My own art style is very specifically photo referenced, which brings its own set of advantages and limitations. Although I've said I work very methodically, I do design my pages intuitively rather than mathematically. I think many of the principles I discuss are best internalized rather than applied analytically. I do feel sure that my future work will be hugely improved by having written this book, and hopefully it will also benefit other creators.

SPURGEON: How much did you enjoy kind of putting into words not just ways to look at material, but certain working tools that cartoonists bring to work like this: the idea of spotting blacks, say, or the golden section or page mark-up. It seems like there's a pride you have in bringing this kind of material forward, this sense of how elegant and thoughtful making comics can be. How did you feel about those kinds of sections as you were doing them?

MILLIDGE: Proud isn't a word I would have used myself, it makes me sound a bit smug and that's not my intention; I'm not claiming credit for any of these techniques and principles, but I am hugely enthused about the vast creative possibilities that comics can offer, and if some of that enthusiasm and love I have for the medium has come across in my text, then I'm happy.

One thing I

was proud of was spotting the Golden Section in a

Gilbert Hernandez panel. I was so proud that I told Gilbert all about my book and that panel from Palomar at San Diego last year. He told me he had never heard of the Golden Section, which popped my bubble pretty quickly. He may very well have been pulling my leg about that, but on the other hand it might also show how great artists create intuitively.

I did learn about the Golden Section at Art School many moons ago, but it was

Bryan Talbot who pointed out its relevance to comic design to me. I think that there are more artists that adjust their layouts until they "look right" rather than meticulously measuring out the dimension of the Golden Ratio, but it's still a helpful and useful thing to be aware of.

SPURGEON: If it's not too much trouble, I was wondering if you could talk about your spotlight choices: Seth, Chip Kidd, Chris Ware, Brian Wood and Matt Kindt. Why those designers? Was there anyone you would have liked to have spoken to that just wasn't available in the way you would have needed to do a full spotlight?

SPURGEON: If it's not too much trouble, I was wondering if you could talk about your spotlight choices: Seth, Chip Kidd, Chris Ware, Brian Wood and Matt Kindt. Why those designers? Was there anyone you would have liked to have spoken to that just wasn't available in the way you would have needed to do a full spotlight?

MILLIDGE: For those sections, I definitely wanted to stress the "graphic design" aspect of the book, so selection was heavily skewed to artist/designers rather than pure artists. There were a few other creators on my shortlist that I didn't eventually include due to a variety of reasons, like reproduction rights issues and suchlike. I think the choices represent an interesting cross-section from the pure design of Chip Kidd to the cartoonist-turned book designers Seth and Chris Ware. Matt Kindt was initially a graphic designer which is in stark contrast to his organic, fluid comic artwork. It's interesting to me that Kidd and Brian Wood are both writers and designers/illustrators rather than cartoonists as such, which underlines the point that design is all about visual communication and that the best comics can be such a beautiful blend of all the visual and verbal arts.

I only wish there more space available in the book to include more images per designer.

SPURGEON: This may be the dumbest question ever, but how much did you contribute to the design of this book, how closely did you work with the art director and the designer? How important was it to you that the book itself be designed a certain way?

MILLIDGE: It's not a dumb question, as I didn't actually have very much input to the design of the book itself at all, and I didn't have any direct contact with either Julie Weir the art director or Jon Allen the designer. There were a few things that I would have done differently, but on the whole I think they both did a terrific job, along with Nick Jones and Isheeta Mustafi, my editors. I ended up turning in about twice as many images as I probably should have, expecting many of them to be dropped at the layout stage; almost all of them were squeezed in somehow, making the book a very rich visual treat in itself. On the whole, I think it might have helped give the book an added dimension by having others to actually edit and design it.

It's ironic that it's a book about design that I didn't design, but then, I had originally been asked to write a book about self-publishing that I wasn't going to be self-publishing.

SPURGEON: Is there anyone when you were making the book that kind of caught your attention in a renewed or more focused way that you maybe hadn't appreciated as fully as you had before?

SPURGEON: Is there anyone when you were making the book that kind of caught your attention in a renewed or more focused way that you maybe hadn't appreciated as fully as you had before?

MILLIDGE: Almost everyone I would say. The very best comics are a storytelling experience; you don't want to be analyzing how well the panels fit together or how appropriate the choice of font is, you should be just carried along by the story.

By analyzing many of the works in the book, I have gained an increased appreciation for a great number of the creators -- off the top of my head I must mention Jim Steranko and Frank Miller, both of which I sort of took for granted in the past. Steranko incorporated much of the design of period, but revolutionized page layout in the process, specifically his last few

Captain America issues. Miller took

Eisner's techniques to a new level. I don't particularly care for Miller's hard-boiled stories, but in terms of comic book design he has few peers.

A less obvious one would be

Paul Grist who effortlessly incorporates every trick in the book without being overly showy, and fellow Brit

D'Israeli displays an extraordinary range of skill.

But in terms of innovation and experimentation, you have just got to hand it to

Dave Sim, no matter what you think of his political views. Apart from the chapter on color, I could have quite easily filled the book with examples from

Cerebus, and that's no exaggeration.

SPURGEON: Is there a reason you didn't use a lot of older work? Because there's not a lot of classic comics in your book. Is it just to give your book some currency, or this is the material you read, or is it by personal choice, do you perhaps not see some of the older books as strong in terms of the designs principles you extol.

SPURGEON: Is there a reason you didn't use a lot of older work? Because there's not a lot of classic comics in your book. Is it just to give your book some currency, or this is the material you read, or is it by personal choice, do you perhaps not see some of the older books as strong in terms of the designs principles you extol.

MILLIDGE: Not sure what you mean by "older work" as I think '60s Marvels are pretty well represented. As I mentioned earlier, we had a rights issue with DC-owned material which knocked a lot of potential examples out. Newspaper strips (along with Manga and Euro comics) were deemed out of the scope of the book, apart from a handful of essential Sunday page strips.

Also, I wanted to concentrate on works that were generally available and in print so that the reader could go and pick up anything that tickled their fancy from Amazon rather than trawling the back issue bins. Part of my intention was to encourage readers to seek out new works.

A lot of the older material was also very poorly printed due to the limitations of the printing techniques at the time, so perhaps wouldn't have reproduced very well in the book.

Having said that, there's no doubt many worthy examples were excluded due to my own ignorance or bad taste and for that I apologize wholeheartedly.

SPURGEON: Are you a different designer having completed the project than you were before?

MILLIDGE: Like I suggested earlier, merely researching the subject make you a wiser man. I bought a number of reference books on graphic design as well as comics during the writing of

Comic Book Design, in order to get a consensus about the things I was writing about, to make sure I wasn't writing total nonsense. I think in the process you can't help but learn and be changed in ways you didn't expect.

I think the biggest change in me as a designer is now I'm a lot more confident in my abilities, knowing that what I've always

felt is right

is actually right, and

why it's right. Plus filling in a few gaps in my own knowledge and realizing that design is as much about aesthetics as art is.

SPURGEON: Gary, I was thinking about doing the research that would enable me to fake that I know the answers, but I thought it might be more honest if I just brought it up and admitted my ignorance. Where do things stand with

SPURGEON: Gary, I was thinking about doing the research that would enable me to fake that I know the answers, but I thought it might be more honest if I just brought it up and admitted my ignorance. Where do things stand with Strangehaven

? And am I right in thinking that we just kind of lost track with you as the market shifted or things went on in your own life... ?

MILLIDGE: Strangehaven has been on an indefinite hiatus since I put out issues 17 and 18 and the collected third paperback

Conspiracies during a spurt of activity in 2005. It's not that I burned out as such, but although the self-publishing of

Strangehaven was always profitable, it never really brought in enough to live on comfortably. I have always been trying to top up my bank account with other jobs, whether they're comic related or not.

2006 and 2007 saw a lot of European editions of

Strangehaven being published, and in between freelance work and being invited to all-expenses paid exotic foreign comic festivals, I didn't really have any time to start work on the next book. I had hoped to do some freelance comics writing, but after spending a lot of unpaid time working on aborted proposals for companies like Vertigo and Desperado, I found myself at a point where I really needed to start earning some money. The past couple of years have been a bit of a disaster both financially and personally, so freelance gigs like

Comic Book Design have become critically important to me.

I do want to stress that

Strangehaven is still an ongoing project; it's never far from my mind and it's always on my drawing board, albeit gathering dust. Of course, over the past couple of years, the landscape of the direct market has changed somewhat and now it's debatable whether I'll be putting

Strangehaven out as a periodical (when eventually I have completed the next issue) through Diamond. Perhaps it'll have to be continued via a POD or online solution, at least until the fourth and final trade paperback is completed. We'll see, they may be other solutions.

SPURGEON: What's next?

MILLIDGE: There are a few personal projects that I would like to started on once

Strangehaven (which is my main priority) is complete, including a couple of self-contained graphic novels, an art book, a novel and a solo album.

In the meantime, I'll be continuing to work my day job as a graphic designer and website designer and perhaps some sort of sequel to

Comic Book Design which I've been discussing with Ilex Press. Fingers crossed!

*****

*

Comic Book Design, Gary Spencer Millidge, Random House, softcover, 160 pages 9780823097968 (ISBN13), 082309796X (ISBN10), July 2009, $24.95

*

Strangehaven, Gary Spencer Millidge, Abiogenesis Press, Ongoing

*****

* cover to the new book, UK

* cover to the new book, USA

* photo by Tom Spurgeon

* example of Matt Kindt's work

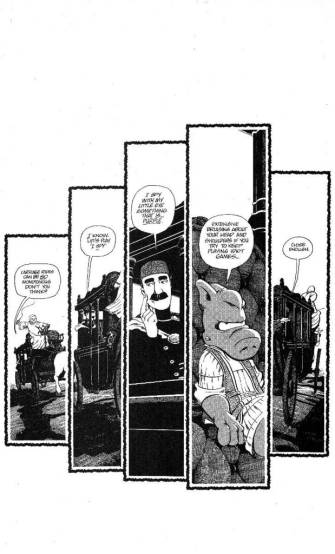

* the always-revelatory craft touches to be found in Cerebus

* page from Master Race included in book

* the last

Strangehaven trade; there are more to come

* short panel sequence from

Strangehaven (below)

*****

*****

*****