Home > CR Interviews

Home > CR Interviews A Short Interview With Douglas Fraser

posted June 18, 2005

A Short Interview With Douglas Fraser

posted June 18, 2005

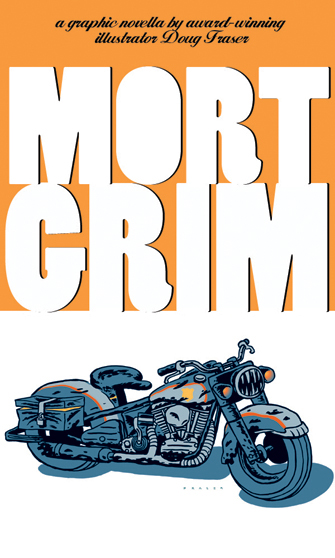

Until I stumbled across news of his new comic book, I knew as much about Douglas Fraser as you probably did. Get used to not knowing who people are all the time. With the explosion of interest in graphic novels and the development of boutique publishers like AdHouse Books, more comics works from talented artists who work the majority of their time in related arts are very much likely. We can hope they're all as visually compelling as

Mort Grim, Fraser's first sustained comics work, a comic that may remind many of something David Mazzucchelli or Graham Chaffee might have made.

Douglas was born in Lethbridge, Alberta in 1961. He was trained as an artist at the Alberta College of Art & Design and studied for a master's at the School of Visual Arts in New York City. His web site gives you an idea of the kind of art he's practicing now, both digital and on canvas, which he describes in humorous fashion as "Brutal Sign Painting, Comic Book Social Realism, and or Specific Generics."

Fraser's

Mort Grim goes on sale July 6, with a planned premiere the following week in San Diego. It costs $5 and its Diamond order number is May052382. Although AdHouse hopes you will buy all of your comics through

your local comic shop, you can also get

Mort Grim through their

web site.

TOM SPURGEON: How did you hook up with Chris Pitzer and AdHouse Books?

DOUGLAS FRASER: We have a mutual friend. I've been illustrating for almost 23 years, and Chris also has a foot in graphic design. As a result, he's seen me as an illustrator. I've always kind of acknowledged the fact that growing up I really enjoyed comic book and they were a big influence in my life. At that point he was putting together the first of the compilations,

Telstar, and I'd done some stuff, too, with Monte Beauchamp at

Blab!, a couple of times. He said, "Would you like to try to do something with this compilation? I can give you a few pages and you can run with it." Chris is such a joy to have met and to have worked with that I seized the opportunity. I jumped at it. Yeah.

Boy, that's a long-winded answer.

SPURGEON: [laughs]

FRASER: Chris heard from a mutual friend,

Kelly Alder, who is in Richmond as well. He said, "Why don't you give him a call? The guy likes comics, and he's always told me he'd like to go for it. Why don't you give him a shot?" So Chris e-mailed me and we got together that way.

SPURGEON: Alder's a fine illustrator, too, as I recall.

FRASER:

SPURGEON: Alder's a fine illustrator, too, as I recall.

FRASER: Oh, yeah. Kelly's a great illustrator, and his brush and ink skills have always left me sucking wind. That was one the things that kept me out of comics. I look at Kelly's work, and his ability to put down such a beautiful line with the brush... I come from a different world. I couldn't do that. I had to accept the fact that I liked the rougher, more spontaneous thing within me, and had to learn to step into that. There were people in illustration doing a line quality something like that, and I was enjoying their work, but personally I kept most of that stuff in my own sketchbook. It was through Kelly and Chris I kind of got encouraged to bring it out into the light of day, I suppose.

SPURGEON: One question I had was why it's taken you so long to try a comic seeing as that's long been an interest of yours.

FRASER: Intimidation! I really respect the medium, and I think storytelling is a whole other layer on top of making a picture. As an illustrator, you resolve things in one panel. As a comic book artist, you go further, you go somewhere else with it.

SPURGEON: In your site's biography, you say you like "certain" comics. Do you have a canon? Is there a short list of greats?

FRASER: I guess I'm rather old school. The people I enjoyed were the Kuberts from the DC days,

GI Combat and the Kirby stuff. I even liked

Bernie Wrightson from

Swamp Thing. Of course comics has gone much bigger now. I also liked some of the storytelling from years ago like

Moebius. There's a lot of new talent doing great work. It's funny. It took me years... I love

Alex Toth. I was late coming to Alex Toth's work but I love it. And another good friend who's been good at coaching me as far as getting out there and doing it is

Ken Steacy.

SPURGEON: You have a graduate degree from the School of Visual Arts?

FRASER: Yeah, I do. I have an MFA degree.

SPURGEON: What was your area of concentration? Did they have "illustration" as an area of study?

FRASER: I was an illustration major. I graduated in '86.

SPURGEON: Most comics readers are aware of SVA for the cartoonists that come out of there. Were there comics around in those days?

FRASER: I bought comics, I read comics... yeah, sure. I was always looking at them. I loved

RAW, really, during the '80s. It was a great thing. It kicked the doors open. I love Gary Panter's work and Charles Burns' work. Again, every generation of comic book artists I would look over at was really pushing the boundaries. They were doing some illustration work as well. I guess as an illustrator I was spending so much time doing illustration and trying to stay viable in that game and enjoying it and doing well at it that it swallowed all my time. I found that if you do anything long enough, I guess you get a little cynical at it. Illustration for me as much as I still love it, some of my youthful exuberance has been polished off. [laughter] It doesn't always fulfill me as much as it used to. I wanted another outlet. I wanted something to take me back to the roots of why I love to make pictures and to draw and to express myself. The opportunity to do a comic with Chris, for me at the time it was both just wonderful and intimidating simultaneously. I had never really contemplated filling up 32 pages of space.

SPURGEON: How did you go about that when the time came? Where did the story come from?

FRASER:

FRASER: The character goes back decades. It goes back to when I was in college I saw the zen film

Electra Glide in Blue, with Robert Blake. Also at that time I was discovering a regionalist flavor to my own work. I grew up in southern Alberta, north of Montana, in a very prairie-esque, farming-based part of North America. I was getting a handle on my own personality, a visual personality, and things were forming. I always remember the far-away shots in the film that I loved so much. [laughs] Of course, Robert Blake is a whole other subject. [laughter] But the movie itself I really enjoyed.

I enjoy motorcycles. I've had one since I was 13. This motorcycle cowboy motif out on the lone western expanse... I had done a number of earlier fallen motorcycle cop paintings for myself personally -- this tragic figure that to me is symbolic of the thin blue line of civility out in the open expanse. I would draw this character. I shelved it for some years, and then about five years ago, four years ago, by Mark Murphy, an editor out of San Diego, a publisher guy, asked a bunch of illustrators to contribute to a book, which was really in essence a rethinking of a sourcebook in the illustration community, trying to add something to it that was not so blatantly crass as other sourcebooks.

SPURGEON: [laughs]

FRASER: Yeah. [laughter] He developed a theme for it and asked everybody to contribute something. And of course we literally paid for our space in there, so it was a kind of backhanded compliment. So I painted up this character that I had kind of evolved in sketchbooks and other ways, I finalized it for myself. I put it in my space for that book. Some people came forward: "That's kind of neat what you got going on there. You should do more with it." At that point, I always wanted to do more; it was percolating. I had drawn the character. It's something I want to draw. It appeals to my feeling of those early motivations as well as an opportunity to talk about some of my own personal... I'm trying to find a word for it... I guess, if you will, self-constructed religious baggage combined with regional imagery.

I wanted it to be kind of a tonal story rather than a blow-by-blow panel of characters talking to one another filled up with speech bubbles. Not to say either one is better; this is where I going. So I developed the drawing. I roughed out a story.

Mark Murphy was at one point thinking he wanted to do something with the character -- that's a whole other thing I don't want to go into at length. I just said I really want to do this on my own. It's my thing, and I want to do it for myself. It was at that point I had the good fortune that Chris came forward and offered me this opportunity. It forced me to get off the toilet. You know the old saying, "shit or get off the pot." I had to pony up here. Which was good. By committing to Chris it forced me to meet a deadline. And I roughed out a story; I started doing my panel layout. All this was new to me. It was so much fun. I enjoyed it. I struggled at times. How I wanted to even do color: four-color, two-color, maybe grayscale, I got to kick around. Once I got a panel structure to it I felt comfortable with I just dove into it. I literally started constructing it when I could in my own time. As an illustrator during the day you're still trying to feed yourself and keep a roof over your head.

SPURGEON: Let me ask you about that panel structure. You're working primarily with three tiers, the width of the page.

FRASER:

SPURGEON: Let me ask you about that panel structure. You're working primarily with three tiers, the width of the page.

FRASER: It's like that horizontal, open, great expanse. When you're sitting in a movie theater, I love that letterbox format. I've always enjoyed a horizontal layout, even when I'm painting. It's a chance to describe that great kind of cinematic, hopefully, take on things.

SPURGEON: One thing I liked is an early scene, during the wreck, where suddenly there's a competing element. The car makes the move around the truck, and this kind of freezes the action because its verticality changes the rhythm on the page.

FRASER: I'm trying to create vertical columns within these flowing horizontal bands. What I was trying to do there is punctuate those events, making them major pillars in the story.

SPURGEON: How was the book actually constructed? Was it something you built in Illustrator, or did you scan things in first?

FRASER:

FRASER: I used an old-school approach. Ken Steacy chuckled that he hadn't seen someone do it for years. I would blue pencil the drawings out on a bond paper, referencing my panel guide, then on top of the blue line I'd work with a brush and ink, a brush and speedball ink. That's what I would do for the black. Then over that I would throw a layer of Mylar -- a transparent paper surface, a paper plastic, quite resilient. Then I could start knocking in where I wanted the next tone to go, like the yellow. I would do a layer for each. Whether it was the 60 percent gray, or the yellow, I would build them as I would go up. A page may have four or five overlays. Then I scan them all into the computer. Whereas in the old days they'd be shot on a line camera, now I'm just scanning them on my scanner in my studio. Then in Adobe Illustrator I'm just basically piling them all on top of one another, the white space being transparent. You create a sandwich of overlays.

SPURGEON: The tones are quite lovely.

FRASER: I wanted a hand quality to the thing. Even when I paint I have a heavy black line that's cleaned up later in the painting as an illustrator because you can get in there and muck about. Ink is a very spontaneous thing. I wanted to be honest to what I was capable of, and what I was doing. I found it very liberating to work this way and to accept my capabilities and my execution.

SPURGEON: It sounds like you're happy with the way the book turned out.

FRASER: I'm really happy. And that's the thing. When you're this happy, it scares me. [laughs] You're checking over your shoulder for the other shoe to fall.

all pictures from Mort Grim except for image #2, which is by the artist and from his web site