Home > CR Interviews

Home > CR Interviews CR Holiday Interview #1—Sean T. Collins On Blankets

posted June 19, 2010

CR Holiday Interview #1—Sean T. Collins On Blankets

posted June 19, 2010

Sean T. Collins lives in Levittown, New York and was I think the first writer to be receiving assignments simultaneously from

Wizard and

The Comics Journal. He currently writes for the

CBR team blog

Robot 6 and for his own blog at

Attentiondeficitdisorderly Too Flat, in addition to a number of print and on-line clients. Collins has an interesting critical voice for several reasons; one that I find particularly useful is that he wandered into this current age of excellent comics as a blank slate. There's not a lot of an industry bottoming out in the late 1990s evident in Sean's writing, as I'm sometimes afraid there may be in my own.

For his list of comics from the decade just past which he'd be comfortable discussing, Collins and I settled on

Craig Thompson's massive

Blankets, published by Top Shelf in 2003.

*****

TOM SPURGEON: Where did Blankets

hit you on your personal discovery of comics and graphic novels? You have one of the more immediate immersions into the art form, so it's always a question I like to ask you. Had you read a lot of big comics like this one before?

SEAN T. COLLINS: It's funny you should ask this. Just a couple days ago I was talking with a friend about whether or not I should do a best-of-the-decade list, and he suggested I think of doing one as a guide for people who are interested in discovering what's good out there but didn't know where to begin. I realized that that was pretty much my story, this decade. Prior to 2001, I wasn't really a "comics reader," though I'd read comics, including

Jimmy Corrigan in the individual

ACME Novelty Library issues. But once I got started in earnest, I jumped in with both feet.

Blankets memorably debuted at

MoCCA in 2003, along with

Kramers Ergot 4 and

The Frank Book, both of which I also picked up, which I think gives some indication of where I was at in terms of my interest in ability to read sophisticated comics. Looking over my

best-of list for 2003, there's

Mat Brinkman,

Gilbert Hernandez,

Marc Bell, plenty of

Ware... in other words

Blankets wasn't a "gateway comic" for me, it was something I consumed alongside serious literary and

avant garde comics, in the same way I consumed those comics. And alongside plenty of Nu-Marvel books too, of course.

That said, in one respect at least there was no comparing

Blankets to anything else, and that was that it was the longest original graphic novel ever published up to that point, in North America at least. So in that sense I hadn't "read a lot of big comics like this one before" -- no one had, because they didn't exist.

Bottomless Belly Button and

A Drifting Life were a long ways away.

SPURGEON: Had you formed an opinion about Craig Thompson? Were you familiar with his previous work?

SPURGEON: Had you formed an opinion about Craig Thompson? Were you familiar with his previous work?

COLLINS: I'd read

Good-Bye, Chunky Rice and liked it a lot, yes. To tie this back to the previous question, that was one of the most applicable contexts in which I could place

Blankets, or at least Craig -- the rapturous and wistful alternative comics starring cute little big-round-headed guys that were all over the place earlier in the decade. I'm thinking of things like Jordan Crane's

The Last Lonely Saturday, which had been a real landmark for me, and a Martin Cendreda mini-comic called

Zurik Robot, and even

Jimmy Corrigan. There's really not a huge leap to be made from the snowy and heartbreaking flashback chapters of

Jimmy Corrigan to either

Chunky Rice or

Blankets, even though Ware and Thompson's approaches to line and layout are obviously very different.

Another important bit of context for me at that time was

Will Eisner's work. When I first read Eisner I wasn't cognizant of the controversy over whether he really merited all the accolades heaped upon him, especially for his later and ostensibly more mature works. From where I was standing he was universally acknowledged as the pioneer of the graphic novel, the Orson Welles of comics. What had happened was I'd interviewed

Frank Miller for my job at the

Abercrombie & Fitch Quarterly and he'd enjoyed it so much that right then at the end of the phone call he offered to hook me up with Eisner for the next issue. So I devoured pretty much any Eisner that

Jim Hanley's Universe had in stock from

A Contract with God onward. Eisner's nakedly emotional approach to narrative, his looseness and borderless freedom with layout, the pantomime body language of his characters, the sweep and lushness of his brushwork, the autobiographical stuff, even his depiction of rainstorms and snowstorms -- that all set me up for

Blankets in many ways.

Finally,

Blankets was something you could grasp in terms of its position as part of Top Shelf's line. The same year

Blankets came out and my wife and I befriended Craig, we picked up

Clumsy and

Unlikely for free courtesy of Brett Warnock and Chris Staros, and we befriended

Jeffrey Brown. So their line at the time, even though it contained

From Hell and

Hutch Owen and plenty more besides, was spearheaded by these heart-on-sleeve Midwestern indie-rock-soundtracked first-love autobiographies. That was an important frame for the book as well.

SPURGEON:

To place that question into a wider context, do you think the timing

of Blankets

worked in its favor? It was this huge and original work, and I'm not certain that anyone had seen this kind of huge and original work done with Thompson's level of skill. It was also being hand-sold with great effectiveness by Top Shelf, at the time when some smaller shows were beginning to take hold... is there anything to be said about this comic and comics of its kind when they become events above and beyond their content?

COLLINS: Oh, yeah, totally.

Blankets wasn't just a book, it was an event. Like I said, it came out at that year's MoCCA, and that was my introduction to the concept of "book of the show." Top Shelf was set up at what had already become its "usual spot" at the bar in the corner of the big ballroom, and you just couldn't miss this huge wall of gigantic powder-blue bricks -- that was

Blankets. The whole show was abuzz about the sheer size of the thing if nothing else. To a lesser but still significant extent this was also true of the other phonebook-sized powder-blue-covered book that debuted there,

Kramers Ergot 4. But what was more, the

insides of both books were just so stunning, visually. When you flipped through them, the impact lived up to the visual impact of simply looking at them, or the physical impact of holding them and lugging them around the show. That was really important.

I think both books -- but especially

Blankets because its art and subject matter were ultimately just so much more accessible -- established that in comics, size matters. Size connotes ambition on the part of the artist. Plus it's an immediately obvious sign that this isn't just some flimsy spinner-rack comic, and back then, when you were

just starting to see the first flourishings of mainstream-media coverage of comics, that was key to breaking through. It's an instant publicity hook and it gets a crowd buzzing. I think that what you saw happen later, at other shows and in general, with the

one-volume Bone and

Bottomless Belly Button and

A Drifting Life and

Kramers Ergot 7, was very much an echo of

Blankets.

And I mean, this is not unique to alternative comics -- look at the complete

Calvin & Hobbes and

The Far Side and the sensation those caused, or DC's Absolute Edition collections. Moreover, we've all learned to conflate size with importance since the first time we heard a

War and Peace joke in

MAD or on

You Can't Do That on Television or wherever. But

Blankets was the first time altcomix had seen anything like that, as best I can tell -- it was certainly the first time

I'd seen anything like that. Plus it was an original graphic novel that hadn't been serialized -- it dropped like a bomb. Plus it was so visually lush. Plus it was an extraordinarily well-designed

object with that powder-blue cover. It leaped off the Top Shelf table, you know? And Craig was there, of course, indefatigably signing copies. As time passed and he continued to tour shows with the book and it caught on and blew up and people had read it and connected with it and were bringing in their own copies for him to sign, he became the closest thing alternative comics has ever come to a heartthrob, too, which also fed into

Blankets the phenomenon.

SPURGEON: You mentioned that you became personally acquainted with Craig, and I mostly want to stay away from that out of respect for the both of you except for this question: could you characterize Craig's relationship to the book in broad terms? Because it's autobiographical, was there an element for Craig of wanting to get that specific story onto the page? Was it perhaps more about achieving a certain amount of skill put to work on a comic's behalf? How do you think he came to regard the work?

SPURGEON: You mentioned that you became personally acquainted with Craig, and I mostly want to stay away from that out of respect for the both of you except for this question: could you characterize Craig's relationship to the book in broad terms? Because it's autobiographical, was there an element for Craig of wanting to get that specific story onto the page? Was it perhaps more about achieving a certain amount of skill put to work on a comic's behalf? How do you think he came to regard the work?

COLLINS: Most of my most direct discussions with Craig about the book took place during shows in 2003 and 2004, so that was the relationship between him and

Blankets that I remember most clearly: just the phenomenon of being the author of that book. Having written the longest graphic novel ever, traveling all around the country and eventually the world, meeting and befriending starstruck readers including my wife and myself, how his life with his friends and his girlfriend was going in the face of all of this, signing so many copies that it literally damaged his hand and prevented him from drawing. Yet for all his and its success he was still very much living the life of a cartoonist. During San Diego 2003 he was sharing a room with three other guys while thanks to my A&F gig I had an in-room jacuzzi all to myself. At MoCCA 2004 he stayed with us on Long Island and commuted to the show rather than springing for an expensive hotel room in the city; he slept on our fold-out sofabed and suffered through the smell of the one and to this day only time our cat ever peed outside her litterbox. The word "whirlwind" comes to mind, though he was never scatterbrained, always present in the moment.

But what you said about "wanting to get that specific story onto the page" was a huge factor for him too if I recall correctly. And it turns out this is borne out by

the interview I conducted with him at San Diego 2003, which I hadn't read in a long time before this discussion. What I remembered most clearly was that the material focusing on his relationship with his first love, Raina, was also inspired in large part by his relationship with his then-girlfriend. Who was awesome, by the way, friendly and funny and lovely, and welcoming to Craig's ever-expanding circle of fan-friends. Anyway, she was the physical model for Raina for one thing. And I'd forgotten this, but Craig said in the interview that when he started working on

Blankets they weren't together -- their separation was the inspiration for

Chunky Rice, actually -- so he poured a lot of his longing for her into the Craig character's longing for Raina. So

Blankets was more of a love letter to her than to the girl who was the basis for Raina, in fact.

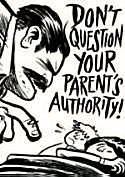

The other major thing was that mailing a copy of

Blankets to his parents was his first admission to them that he was no longer a Christian, let alone of all the other uncomfortably intimate moments he was sharing in that book. They were still every bit as devout as they were during the childhood and teen events depicted in the book, so this took a great deal of courage on Craig's part and caused him a great deal of pain. Imagine sending your magnum opus to your parents and their reaction is concern, because this means you're going to Hell. That's literally what they told him. So that was hanging over his head constantly as well -- though I know it felt good for him to break the logjam of communication that had prevented him from ever honestly and openly discussing this with his parents before.

SPURGEON: One thing I was struck by looking at the book recently is that it's so very pretty. There's an element in comics that tends to disregard the effect of art altogether, a faction that almost talks about the art in a comic book as if it were an empty vessel in service of the writing.

SPURGEON: One thing I was struck by looking at the book recently is that it's so very pretty. There's an element in comics that tends to disregard the effect of art altogether, a faction that almost talks about the art in a comic book as if it were an empty vessel in service of the writing.

COLLINS: That's true, and not just in the usual sense of overemphasizing the plot or the dialogue or what have you. A couple of days ago I read

that Comics Journal conversation between Art Spiegelman, Kevin Huizenga, and Gary Groth, and it's just the latest place where Spiegelman describes cartooning as a sort of picture-writing, where your style is like your handwriting, and the images are pictograms. As Huizenga pointed out in a different context elsewhere in the interview, it's sort of contrary to his earlier notion of comics as a "co-mix" of word and picture, since he came to see them as inseparable.

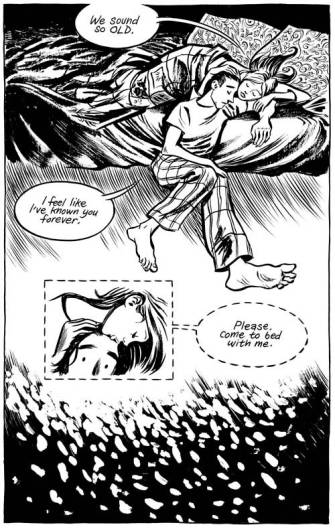

Blankets is subtitled "an illustrated novel" -- not so accurate in terms of what we usually understand a novel to be, of course, but bringing "illustration" into the equation makes a lot of sense, I think.

SPURGEON: Can you talk some more about how much of what

SPURGEON: Can you talk some more about how much of what Blankets

did for people came from its very elegant art and Craig design sense? How would the work have been different if a good artist without Craig's particular flair had handled the art chores?

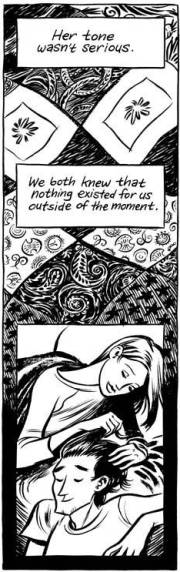

COLLINS: Well, like I said, it grabs people right away. It just looks inviting, like something it would be pleasant or even delightful to spend 600 pages looking at -- and for a book this size that's hugely important. To compare it to other "crossover" hits from a few years back, imagine if

Ghost World were 600 pages long! People like you and me might give their eye teeth to wallow in Clowes for that length, but bye bye bookstore sales -- a civilian's eyes would just glaze over. In that interview I did with him, Craig said that he agreed with non-comics readers that your usual comics page is "claustrophobic." With his sweeping line and frequent splash pages and abandonment of panel borders and absence of a grid and so on, he was trying to open things up. So that was key, I think. That's what made my wife make the transition from flipping through the copy I'd left on the kitchen table to grabbing it and reading it all in one sitting to, eventually, getting that recurring mandala symbol tattooed on her person. I mean, that was also because it reflected events in her own life so uncannily that it was all but written about her, but as a comics civilian she never would have gotten there without the look of the thing first and foremost, and the easy, graceful reading experience it enabled.

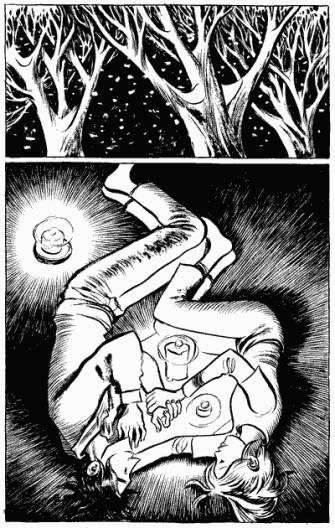

But it's not a picture book, it's a comic, and to get back to the Spiegelman definition for a moment, form and function mesh pretty perfectly here. It'd been years since I'd last read the book before I re-read it to prep for this conversation, and the thing that struck me

immediately was just how openly, nakedly, ecstatically

emotional it is! Right from the get-go, from the first scene with Craig and his little brother in bed, they horse around like cartoon animals, then their Dad shows up all angry and he's drawn as a hulking shadowed

ogre, then little Phil gets locked in the cubbyhole and it's full of

monsters and

demons and

spiders, it's like

Hell, and he screams and cries and pleads and panics and ultimately despairs, and Craig is just

devastated. That's the first scene! It's all peaks and valleys. Then it happens again, right away, with Craig getting bullied at school. And so on for 600 pages. In this re-read, it became obvious to me that what many people write off as cloying or melodramatic or emo was a conscious and utterly in-control choice on Thompson's part to pitch everything to the balcony, because that's reflective of how it felt in the moment. At one point Raina makes fun of Craig's flowery way of speaking, which of course is the same way the whole book is narrated in past tense -- I think that gives the game away right there, that Thompson is perfectly aware of how this all looks and reads. And again, you couldn't get there without the surface beauty, kitschy though it may seem to some. You add an edge to it and it falls apart.

SPURGEON: There's been a bit of backlash against Blankets over the years, and one of the responses by some of its supporters has been to point out that it's a book best intended for teens. What do you think of that as a) an accurate description of the book, b) as a deflection against criticism?

SPURGEON: There's been a bit of backlash against Blankets over the years, and one of the responses by some of its supporters has been to point out that it's a book best intended for teens. What do you think of that as a) an accurate description of the book, b) as a deflection against criticism?

COLLINS: People really say that? Hm. Wow. As a defense? Huh. I don't think it's a book best intended for teens, I can say that much. I never thought about it that way, I've never thought about it that way actually. Certainly that never came up in all the conversations I had with Craig about it. Is the idea that he intended it that way, or just that that's how it came out?

I mean, obviously it'd be an amazing book to have and study and hold close to your heart and moon over/fap to the sexy Craig and Raina pictures as a kid. If my wife and I had had something like this when we were long-distance courting by mail as teenagers -- Jesus. The doomed glamor of it all! And even aside from that, it really does just nail the specifics of that situation. Having a hard time eating around this person because you're so infatuated, wearing their clothes once they leave, the dread and hatred you feel for the passage of time because it means they'll have to leave, missing someone while they're still there, sending mix tapes and letters and all sorts of treasures through the mail... some of that stuff I'd forgotten until I re-read it just now, and wham, it hit me like a freight train. The validation that seeing this depicted would give a teenager, I imagine that's just phenomenal.

But the thing is, as teenagers we'd read it as an endorsement rather than as an observation. And it

is an observation of past behavior by an older and wiser young man. That it manages to recapture those moments without condescension is remarkable, but it

is recapturing them and presenting them through the filter and remove of someone who can look back and see his past emotional and intellectual excesses for what they were. Frankly I think that not seeing this betrays a lack of sophistication on the part of the critic, not on the part of the book.

SPURGEON: Can you describe one or two places where you think Thompson achieves a distance from what he's recording, where it is clearly about observation rather than endorsement?

SPURGEON: Can you describe one or two places where you think Thompson achieves a distance from what he's recording, where it is clearly about observation rather than endorsement?

COLLINS: Aside from the bit where Raina makes fun of the way he's speaking, which is the same way he's been narrating the comic, I think the big tell is the material with Raina's father. When Craig and Raina first rendezvous at the drop-off point and her dad drives them back to their house, Craig mockingly contrasts his happy mile-a-minute chatter with Craig and Raina's silent exchanged glances and whatnot: "Raina's father Steve seemed full of enthusiasm, but I knew OUR enthusiasm was more sincere." But then Craig -- author Craig, not character Craig -- goes on to punctuate that whole romantic middle third of the book with little glimpses of Raina's parents' dissolving marriage, Steve's difficulty connecting with Raina's brother Ben, and of course that final scene where Steve catches Craig and Raina sleeping together shirtless but instead of busting them, he just sits down and looks at the family album. Obviously that's not something Craig could have seen or known in real life. I think it was added to belie character-Craig's first impression of Steve and his superiority to him. Character-Craig is all caught up in his first love, but the great love of Steve's life is falling apart at the same time. I imagine his enthusiasm was no less sincere than Craig and Raina's back in the day.

Moreover, the lynchpin of the final third of the book is the Biblical passage that really keyed Craig into the ambiguity of that text, the thing about "the kingdom of God is around and/or within you." Earlier in the book, everything Craig did he did with the grand gestures of absolute certainty. He doesn't just stop drawing when he feels like it's too secular and selfish a pursuit, he destroys all his old drawings. He doesn't just break up with Raina, he cuts off all contact with her and burns up almost everything she ever gave him. The final section strikes me as a repudiation of the kind of Romantic absolutism that animated most of the book. Now to be fair, I'm cheating a little here, because in that interview Craig came out and said that he cut off contact with Raina because he was a kid and couldn't handle it otherwise. In other words I knew for a fact it was an observation rather than an endorsement. But I think it's present in the text as well.

SPURGEON: You told me in an out-of-interview aside that your re-reading of Blankets

indicated to you that it was better than your memory of it. Other than the observational specifics you mention above, can you describe what led you to hold it in greater esteem? And why do you think that occurs to you now and maybe didn't then?

COLLINS: I think the main thing is what I said earlier about how openly emotional it is, and the reason I like it more now is because I've read an awful lot of comics since then, far far more than I had even at the time, and you just don't get that very often. That's not to say that there aren't many alternative and literary and art comics that were designed to have a major emotional impact on the reader and in my case succeeded -- just that the way Thompson foregrounds that, and the resulting pacing and layout and line and figure work and so on -- it's really unique. Particularly the pacing, I'd say. It was just a pleasure to read something I hadn't really seen done elsewhere and have enough under my belt to recognize that.

SPURGEON: Do you feel

SPURGEON: Do you feel Blankets

has something to say about the act of making art? It's easy to see how Raina acts as a muse for the graphic novel's Craig, but there's also a struggle he has in rectifying art to his Christian beliefs generally. Even on the page, you could say that the way he approaches this story reflects a feeling to be more specific (the posters in Raina's room, say) and present in his art than he maybe was in the funny animal stories he'd done before. At the same time, the dude is engaging those issues while creating a 600-page comics story.

COLLINS: I'm not following what contrast you're drawing with that last sentence... Uh, actually I don't know if I have much of value to say on this point. I think you just summed up most of the obvious points about making art that the book makes. [Spurgeon laughs] Maybe what you're getting at is that throughout most of the book Craig sees life and art as being at odds.

SPURGEON: Yes.

COLLINS: There's obviously very little room for it in the Christian fundamentalist worldview to which he is exposed and to which he ascribes. But even before he becomes involved with Raina he reacts with discomfort and disgust to the mass singalongs at Bible camp -- he seems to see art as solitary rather than communal, and that's a separate issue from how drawing a naked lady makes Jesus cry or how his Sunday school teacher said he couldn't possibly glorify God by drawing his creation since God already drew it. And then later, with Raina, as much as she's his muse, when he's with her he doesn't want to draw at all, since her existence is a superior substitute for the act of making art. Perhaps going back and making a 600-page comic about it all was his way of reassuring himself that art and life need not be at odds, that art can be an important part of life. You see that, a bit, when he tries to reconnect with Phil and encourages him to never stop drawing. He heeded his own advice, I guess. I mean, you can't read the last few pages and the captions about "How satisfying it is to leave a mark on a blank surface" without thinking about how he'd just done exactly that 580 times.

SPURGEON: I think people tend to conceive of Blankets

in terms of at the book's evocative, romantic middle rather than its last third. It's not always what Thompson thinks about the experience in its entirety, and that's to his credit, but what do you take away when you look at the book as a whole rather than breaking it down to its admittedly lovely parts?

COLLINS: Well, I think the central metaphor of blankets works better as a metaphor than as a real binding thread. Craig said in my interview that the germinative idea was what it's like to sleep with another person for the first time, and then he realized that he'd of course shared a bed with his brother for years, and the story grew from there. But for me, Phil never becomes a character the way that Raina does. There's not really a parallel story being told -- the Phil material is just a frame for further coming-of-age stuff, introducing Craig's harsh family dynamic, providing a contrast between the "filthy" pee fight and how un-filthy he feels being sexual with Raina, and so on. The Raina material is the meat in the sandwich, so I don't blame people for focusing on that. But it's much more than just that boy meets girl, boy loses girl story. It's not

Unlikely, with its laser-like focus. It's also about growing up in the rural Midwest, it's about being brothers, it's about a certain strand of American Christianity and the damage it does, it's about having well-meaning but psychologically abusive parents, it's about loss of faith, it's about cartooning, it's a portrait of the artist as a young man, to a certain extent it's about Raina's family and the issues of divorce and adoption and caring for the mentally disabled that are raised there, there are some nice little mementos of the grunge era... it's a big book with big aims, and you lose sight of something important if you reduce it to just the love story. I have no idea if that answers your question.

SPURGEON: That works. Do you think

SPURGEON: That works. Do you think Blankets

has been influential? Is comics different now for this book being published? What made you think of it as an emblematic work of the decade?

COLLINS: I think the format is more influential than the content. Other than a handful of pretty minor works I don't think you can point to an important graphic novel and say that it was written or drawn like

Blankets. At least, not in the circles I run in. Indeed, I think many of Craig's methods and priorities here were roundly and soundly rejected by Altcomix Nation. Possible exceptions are

Skyscrapers of the Midwest, though I think that has more to do with Chris Ware, and maybe

Jeff Lemire's Essex County trilogy, which of course is another Top Shelf release. That said, I'm guessing there's dozens of young artists that this book hit like an atom bomb who are out there doing webcomics I'm not reading or making minis I'm not buying, and perhaps one will emerge with a major work at some point.

But the way the book broke was a big deal, for the reasons I described earlier, and now

Blankets is sort of the default mode for how to create a breakout graphic novel. You aim for a giant fat book instead of doling things out in serialized installments. Even in 2003 that was still a dicey proposition -- I know Craig took flack from other cartoonists for it, and I know he lost out on income he could have made through his cartooning for a long time while he toiled to produce 600 pages. Nowadays it may still be economically treacherous, but no one would look at you like you were crazy if you told them the reason you hadn't been releasing work is because you were storing up for a 700-page book about high school.

Which is another thing: Memoir is a huge deal, and if you can tie it into a hot-button issue like religion, so much the better. I think it was probably easier for this decade's dabblers-in-comics to see

Blankets in

Fun Home or

Persepolis than to see

Maus in them. They'd

reference Maus if they were writing those books up for a magazine, sure, but I think Spiegelman's agenda has a lot less to do with those books than Thompson's.

Meanwhile, I'm not even close to knowing all the specifics of it, but I think Craig was the first of the post-

RAW generation to at least be rumored to become very successful thanks to comics. There was that photo op of

Chris Staros giving him a $20K check at Wizard World Chicago -- wow, talk about changing times -- and then of course he decamped for

Pantheon for altcomix's rumored first six-figure payday. It's easy to see why a company like Pantheon would want to work with guys like Ware or Clowes or Burns, but I think a person of Thompson's age and level of output opened doors in a way that those guys didn't.

This is all making

Blankets' impact sound pretty mercenary and gross, though, which I don't think it is. Partially that's because I think that most of what I just went over has been good for comics. But it's also because it has very little to do with why I suggested

Blankets as one of the decade's major works. So to answer your question of why, it's because I'll never ever forget that MoCCA when it came out, the immediate impact it had on the scene. Everyone had to have an opinion about it and passionately defend it. It got people talking, and it got people

reading, more than any comic I'd actually been around to see come out up until that point. It did so because it just plain

worked in an immediate and obvious way. If I had a nickel for every time I saw it show up as the only comic on some LiveJournal list of someone's favorite books, I'd probably have a couple bucks. It's one of a very few books that you can point to and say "There, that's a book that made comics

happen this decade." Now, I happen to really like it, so my hope is that other artists might ask themselves how it pulled this off, and return to it and read it and learn from it and apply it. There's gold in them thar hills.

*****

*

Blankets, Craig Thompson, Top Shelf Productions, softcover, 592 pages, 9781891830433, 2003, $29.95

*****

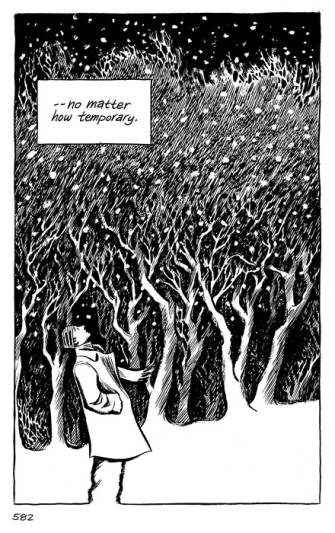

* all images from

Blankets except the last one which I think is an unused cover for an edition, an image that I had sitting on my hard drive for some unspeakable reason.

*****

This year's CR Holiday Interview Series features some of the best writers about comics talking about emblematic -- by which we mean favorite, representative or just plain great -- books from the ten-year period 2000-2009. The writer provides a short list of books, comics or series they believe qualify; I pick one from their list that sounds interesting to me and we talk about it. It's been a long, rough and fascinating decade. Our hope is that this series will entertain from interview to interview but also remind all of us what a remarkable time it has been and continues to be for comics as an art form. We wish you the happiest of holidays no matter how you worship or choose not to. Thank you so much for reading

The Comics Reporter.

*****

*****

*****