Home > CR Interviews

Home > CR Interviews CR Holiday Interview #16—Ben Schwartz On BPRD

posted June 19, 2010

CR Holiday Interview #16—Ben Schwartz On BPRD

posted June 19, 2010

Ben Schwartz and I used to write for the same on-line magazine. He has since put together an awesome resume in terms of writing about comics, a list of dream gigs that I coaxed out of him early in the interview below. I chose

the BPRD books from the short list of comics Schwartz provided.

Mike Mignola's

Hellboy was one of the signature comics creations of the 1990s, but

the spin-off series featuring various supporting characters from the original title is very much a creature of this decade: influenced by the movies, working both serial book and classic comics-format markets, split between various genres, beholden to one creator's work while allowing several hands in on the process. I couldn't wait to hear what Schwartz had to say. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: Ben, I think you're probably a pretty unfamiliar figure to readers of this site. How did you end up writing about comics? What are some of the better-known pieces of the last five years or so? What's the basis of your specific interest in comics?

BEN SCHWARTZ: Hi Tom -- well, I guess the pieces I've done that got the most notice would include

the comics reprints Sunday feature I did for the NY Times. I interviewed Joe Matt and several publishers, editors, and collectors about how fan collections (like Joe's amazing

Gasoline Alley set) and digital media make the current strip reprint renaissance possible. Literally, a combination of paste and scissors technology and Photoshop scanning is preserving whole bodies of work -- pretty amazing. Besides the cranky letters I write you, your readers might know me from

Comic Art where I've written about

Charles Schulz' return home from WW II and the beginnings of

Peanuts, as well as profiling

Kaz and

Drew Friedman at length. I write reviews of comics and other books for

Bookforum, the

LA Times,

Washington Post, the

Chicago Reader. I wrote about them for

Suck.com as Bertolt Blecht. I've sold screenplays to filmmakers

James Cameron and

Arnold Kopelson (which remain unproduced, goddammit), and written a Captain America special with Howard Chaykin ("Blood Truce"), gone to

the Indy 500 with Peter Bagge for Suck.com, and wrote a biographical piece on

James Thurber with

Ivan Brunetti, "The Thurber Carnivore."

Why do I write about comics? Well, I've been staring at comics since before I could read. I was three when my mom gave me a

Gold Key Disney digest (the one with Carl Barks' "Trick or Treat" in it). So, I have a lot emotionally invested in them. In recent years, literary comics and the interest in them mean it's a way into mainstream newspapers and magazines. I've finished a profile for

Vanity Fair on a cartoonist (who I can't name, as the piece hasn't run yet). I don't know any other way for me into

Vanity Fair. I know what to ask an

art spiegelman, but not

Gisele. There's 1000 writers on movies and books and whatever else I write about, but comics is a smaller field.

SPURGEON: There's two things that you mentioned in an e-mail to me that I was wondering if you'd repeat and unpack a bit in terms of your general outlook on titles such as

SPURGEON: There's two things that you mentioned in an e-mail to me that I was wondering if you'd repeat and unpack a bit in terms of your general outlook on titles such as BPRD

. The first is that you'd been enjoying superheroes anywhere but comics for a while now. The second was that you'd be rediscovering the appeal of such characters through the eyes of your son, who also was coming at them with almost no comic book knowledge.

SCHWARTZ: Since college, I pretty much wrote off the superhero as a concept. That happened right after

Dark Knight and

Watchmen came out, and I didn't love those books. While I saw their quality upgrade over most hero comics, I felt they were a swan song for the era I grew up reading, from the '70s thru the mid-'80s. Whereas today, many many readers see

Watchmen as an entry point. Different perspective. Both books are compelling arguments about the futility of superheroes. Although, I have to say, punching reality holes in the teenage fantasies of

Bob Kane,

Siegel and

Shuster, or the

Ditko/

Kirby Marvel Age isn't exactly going ten rounds with

Tolstoy.

I always thought the weak point of both were their political and governmental view of America. Not for my own particular left-right partisan ideas, but say, the idea that

Nixon would still be in office in 1985, that superheroes are outlawed... I mean, this country won't even outlaw masked criminals like the

KKK, eco-terrorists, or organized criminals like

LA gangs and

the mafia. If they can't catch

bin Laden and took decades to catch

the Unabomber (and only when his brother turned him in), what's the government going to do about Spider-Man? This is a country that threw a fit over

Caller ID -- until they were guaranteed their privacy. Also,

the whole nuclear clock thing was specifically a Reagan issue, not a Nixon issue -- Nixon was actually disliked by the far-right for détente and going to China. Maybe

Time-Warner vetoed using

Reagan, I don't know. When

Watchmen and

Dark Knight came out, I was in college, reading more about politics and government. Let's just say, I find

Alan Moore's

Dr. Manhattan more believable than his Nixon. Then again, I'm perhaps the only pre-2009 reader of

Watchmen who actually likes the

Watchmen movie as much as or more than the comic. Anyway, except for Moore's

career on Supreme or

League of Extraordinary Gentelmen, I skipped most superhero books after that. For all my

Watchmen complaints, I still think Moore's "

Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?" is his greatest superhero story, and may be the greatest story DC ever published.

Anyway, two things happened that made superheroes interesting again. First, the movies: I've seen very few

Spider-Man,

X-Men, or

Batman comics that compare to the great movie adaptations of the last ten years. Is there a better superhero story than

The Incredibles? The people who make the movies do an amazing job of relating superheroes to a non-direct sales comics audience. Until the movie, for example, I never found Iron Man that entertaining in my life: a secondary character, a good Avenger with a boring series and the worst villains ever (

Whiplash?

The Unicorn?

The Melter?). I like how the movie uses a pulp hero to ask questions about America's current wars. It reminds me of how

John Ford approached the Western or

Kurosawa the samurai film. Most superhero movies feel like high-tech westerns to me. Marvel and DC tend to use super heroes to ask more questions about superheroes. I once wrote in to

CR with a joke about

Frank Miller saying he wanted to do

a Batman v al-Qaedah comic. After seeing

Iron Man, which dealt with who we arm and why, I take it back. I'd like to see what Miller does.

The second way superheroes came back into my life is my son Archer (now 3) through toys and cartoons he likes. He loves

The Incredibles and Fleischer Brothers

Superman shorts (I always jump to the fast forward when "Japoteurs" comes on),

Speed Racer,

Astro Boy -- as well as

Yo Gabba Gabba,

The Backyardigans, and

Li'l Bill. I got Archer some action figures to play with and he loves superheroes that way or watching shorts on Youtube. The Fleischer

Superman is great example of what happens quality-wise when you wrest these things from the hands of the fanboys. It's hard to look at Joe Shuster's mediocre art after the Fleischers' perfected his Golden Age Superman. Obviously, it's all about execution, whether to a three-year-old or me and

the Nolan Batman movies. Archer has a Fisher-Price Imaginext Batman and Joker, and they're totally kid friendly in design. Archer dismissed the

Brave and The Bold show as "too fighty." I agree, it was very much a grim, violent cartoon, done in a cartoony style to sell toys, I guess (uh, we have the Blue Beetle and vehicle). His Fisher-Price Joker drives a purple motorcycle with a clown's hammer on it that bops good guys. A Galactus I owned from the 90s currently towers over the

Yo Gabba Gabba gang on his play table. Marvel does

Superhero Squad for kids, too.

Disney's buyout of Marvel makes me hopeful a

Floyd Gottfredson or

Carl Barks will emerge one day in superhero comics. I'd like to think it's why Otto Binder and CC Beck's Captain Marvel reportedly outsold Superman -- because it had a hipper view of the

Marvel Family than DC's dullard Superman. I look at them now and get the ironic, absurdist gestures the way I do the lit references in Chuck Jones cartoons. It's probably why I find that Binder and Siegel wrote my favorite DC comics of the '50s and '60s (the

Jimmy Olsen,

Legion stories) because they're knowingly absurd (and Binder, much more than Siegel).

SPURGEON: While the BPRD

books are a creature of the last ten years in comics publishing, Hellboy

seems to me one of the key books of the decade before that. How familiar were you with that book and its core characters coming into the BPRD

books? When did you discover Mike Mignola and what were your initial impressions of his work?

SCHWARTZ:

SCHWARTZ: Not familiar with

BPRD at all and I wasn't familiar with

Hellboy outside of knowing that it existed. I remember its debut, which I did not read, as I thought it looked Kirby-derivative and the name struck me as skateboarder cool. Like skate kids who say "bad boy" a lot. You know, "Check this bad boy out," as the kid does a leap off a handicapped ramp at school and lands back on his board. Also the

Ben-Grimm-in-a-trenchcoat look and the big gun, I thought, "Is he supposed to be a badass

Cain and Abel or

Cryptkeeper? I never read it. Honestly, I was struck by a

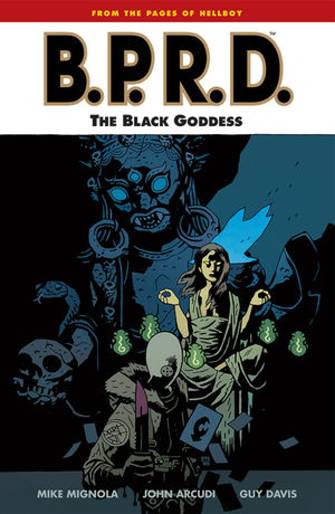

Kevin Nowlan cover for the

BPRD "Black Goddess" cycle. I immediately liked that

BPRD is a kick-ass action comic, which is rare in mystic-themed comics.

The Phantom Stranger,

Dr. Strange,

Dr. Fate -- they stand around reciting spells and lighting incense. Strange wears a leotard, for God's sake. Gaiman's

Sandman made the fey stuff work. Ditko's Strange at least has physically intimidating villains and magic bolts that can knock Strange on his butt. Mignola's is a Kirby-inspired magical world, so it's magic with some muscle. I read back thru all the collections of

BPRD and really got into it. I looked at the early

Hellboys on up, and I still wasn't into him alone as much as

BPRD. Then again,

BPRD stories take advantage of everything Mignola and his collaborators built up previously in

Hellboy (the frog plagues, all that history). It's like comparing

Steamboat Willie to

Fantasia.

As for Mignola himself, his career really took off when I had no interest in genre comics, so I missed out. A friend (collector

Glenn Bray) showed me some Mignola stuff he liked. Glenn, btw, is also the executor of sculptor and painter

Stanislav Szukalski's estate. As a total coincidence, unknown to Glenn until recently, Guy Davis used some Szukalski inspired designs for his ancient world technology in

BPRD. But, really, the black goddess covers sold me. Jack Kirby once told me he used to draw covers so you could see them a block away, and that's how Nowlan hooked me.

SPURGEON: I think most people enjoy BPRD as straight-ahead entertainment; is there any argument to be made for anything else they do well? Is there anything formally ambitious in any of the series that struck you as interesting, or is there a metaphorical thread or two that gets revealed at any point? Are they ever entertainment-plus?

SPURGEON: I think most people enjoy BPRD as straight-ahead entertainment; is there any argument to be made for anything else they do well? Is there anything formally ambitious in any of the series that struck you as interesting, or is there a metaphorical thread or two that gets revealed at any point? Are they ever entertainment-plus?

SCHWARTZ: As far as the hero genre goes in comics, yes. Setting superheroes in this world rather than the usual mystery man world we've seen since the 1930s is innovative. (More about this later.)

BPRD is a great repository as well for so many modern and ancient horror myths, religious, cultural, or purely fictional. It's like

Aliens set in a supernatural world, too, with this special forces team versus the paranormal mentality.

BPRD has that Gen X thing that

Tarantino and great hip-hop like the

Beastie Boys do, of synthesizing and sampling a whole genre and then handing it back to you. In this case, a demon hero, Hellboy, and

Liz Sherman, a

Stephen King firestarter, battling

Lovecraftian cult frogmen and their gods. That is, theological demons v. Lovecraft, classical Old World horror v. modernist horror -- a great clash of genre and ideology, and that's the jumping off point.

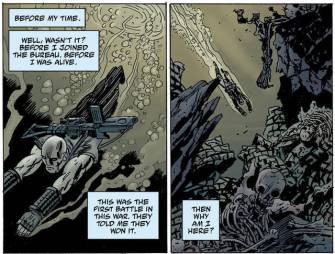

There's lots

BPRD does better than most genre comics. Stories are lean, the characters are always present. They build on a continuity that doesn't require you to buy 20 titles. Like the best horror, you're creeped out by atmosphere and the pathetic dehumanizing of life -- then the monster shows up. Davis has a subtle gift for pausing on faces, revealing characters in silent reflection and with perfect mood.

Arcudi and Mignola load these characters with plenty of mystery and avenues for self-discovery, like Liz Sherman's future in the

Black Goddess cycle or Hellboy's fragmentary knowledge of his future or

Abe's of his past.

Johann's existence, and the amoral territory in which his desire to feel again leads him, is funny and sad.

Still, there's definitely a ceiling to the ambition. As far as genre goes, this isn't

Cormac McCarthy restating the Western in

Blood Meridian or

James Ellroy's radically rewriting

noir as historical fiction in

American Tabloid. The advantage of a self-contained literary model is that you can do that in one great work. A soap opera continuity dilutes that. If the frog plague is meant as some metaphor for AIDS or conformity or the dumbing down of America or something, I don't get it.

Hellboy and

BPRD strip a lot of the serious theological stuff off these characters. I mean, Hellboy's a demon with a heart right? Is he going to team-up with St. Paul anytime soon? I'm Jewish, so if there's a deeply Christian thing going on, feel free to point it out. A lot of these creatures -- Hellboy,

Hecate, the frogs, the mummy in the bed, the leprechauns, the Lovecraftian space horrors -- theologically, how do they all exist together? That's a question Alan Moore would want to answer. Mignola, I'm guessing, isn't going to explain such things.

The creative team behind all this is clearly serious about their characters and the world they inhabit. If they think seriously in

BPRD about ours, I don't know. And I'm OK with that, it's not what I want from it. Now that the "graphic novel" era is upon us, superhero books aren't the sole representative of the medium in the public's mind. Who needs such statements on modern America from

BPRD when

Ware,

Clowes,

Tomine and

Los Bros are on job?

SPURGEON: Do these books ever work as satire at all? Certainly the basic

SPURGEON: Do these books ever work as satire at all? Certainly the basic Hellboy

formula of these awesome horror images and this wisecracking character at the center of it all called attention to the excesses of the genre. I'm thinking of a character like Memnan Saa in The Black Goddess

, which seems to be a noir/pulp character brought to life. Is there an attitude toward the source material that you can get out of the various book series?

SCHWARTZ: Saa is a particularly effective "villain," if he is that, in his assessment that only part of the world can be saved from the frogs and their gods. There's something about his resignation to this that is so anti-heroic... I love it. Saa is a great example of what they do. He's a Fu Manchu "type," but the back story they give him is human, from discarded mystic wanna-be in Victorian England thru so much degradation to what he is now.

Yes, it's satirical, and in the best way. What you described in

Hellboy, the wisecracking, is funny -- I especially liked that iron keys "tale" with the asshole leprechaun. But there's a bigger sense of fun to

BPRD. Lots of comics back to

Action #1 feature a wisecracking hero laughing at enemies the rest of us need to fear --

BPRD is different.

BPRD: 1946, the story of Hitler's Operation Vampir Sturm, is a great example. There's no terrible reverence for the Nazis. I don't need to hear about Auschwitz in a monster comic. Leave that to

Maus. Here, Nazis are bad guys injecting lunatics with vampire blood to unleash them on the allies -- in experiments conducted by a bald decapitated Nazi scientist using a robot spider body and giant brain controlled gorillas as his musclemen. Plus, there's that Soviet BPRD counterpart, a Lord of Hell in the shape of a little girl in a white dress holding a dolly. There's a hilarious over the top-ness to it that never loses the story -- not easy to do. I mean, the Nazi scientist's name is "Von Klempt," I assume, from "verklempt," and it still works! It's a version of Binder absurdity aimed only at adult readers. I wasn't kidding when I said I loved Siegel and Binder's writing (they had Jimmy Olsen time traveling back to Nazi Germany as Field Marshall Olsen, for God's sake) and

BPRD has that quality in a far weirder, compelling story style. The BPRD team obviously love comics and their cliches and are quite aware of how absurd it is.

One of my favorite movies as a kid and now is

Abbott and Costello Meet The Invisible Man (1951), from a story by two of Jack Benny's writers,

Wedlock and

Snyder. In it,

Bud and

Lou are private detectives (always a great start) who get involved with a boxer on the lam from gangsters -- for not throwing a fight -- and the cops (as a falsely accused murderer). He takes

Claude Rains' invisibility serum (some character in the movie is Raines' great granddaughter or something, and they have Raines' 8x10 on the wall, to tie the franchise in). Then Lou has to get in the ring and box with the invisible boxer next to him, who then has to leave the ring for a while, so Lou gets pounded. Ok, four genres: boxing, gangsters,

Invisible Man sequel and simultaneous Abbott and Costello comedy. Top that! Absurdity is not something DC or Marvel can traffic in much. I mean, they're already teetering on "

Superduperman" everyday as it is.

Otto Binder and

CC Beck produced a great comic at their

Captain Marvel peak, with hilariously snide comments about how dumb Marvel is and the total evil that is the

Sivana family. Like the one where the Sivanas rob the Marvels of their powers and chase them on horses in a foxhunt with Dr. Sivana shouting, "The sport of kings!" It worked for me as a little kid and as an adult, but not in-between. Binder and Siegel gave us the Bizarros and Superpets and

Mr. Tawny and

Mr. Mind. It's lighter in tone than

BPRD, but no less hip.

SPURGEON: What is the nature of the enjoyment you derive from the series? Can you provide a general critical overview? Which ones have work better for you than the others? When these books are working, what are they doing for you that other comics don't?

SPURGEON: What is the nature of the enjoyment you derive from the series? Can you provide a general critical overview? Which ones have work better for you than the others? When these books are working, what are they doing for you that other comics don't?

SCHWARTZ: I'm the wrong guy to ask about what other books are doing out there re superheroes.

BPRD is an unfolding serial, so an overview is hard when the story could be half over or 9/10 done for all I know. Overall,

BPRD manages with deceptive ease an epic storyline with human, driven characters at its center. It's as much about Liz and her gradual acceptance of what she is and what her abilities cost her (from her family as child to her unwanted role at the center of Memnan Saa's vision) to our apocalyptic frog future. Abe's broken heart and Johann's isolation fit perfectly into this cosmic/mystic epic. They can tell a multi-part story that's really one "chapter" in the overall story (like

1946), jump to Nebraska "now" in

The Black Flame, or visit Abe Sapien's Civil War past. A great example in

1946 is the German mom hiding her loony vampir son in the barn, not wanting more soldiers to take him, despite what he is. Heartbreaking, weird, a mother grasping at whatever she can of prewar life -- despite how warped and lost her son is.

I actually get creeped out reading

BPRD. I get emotionally involved in the characters.

BPRD combines a number of horror and superhero elements I love, from Lovecraft to Cameron's

Aliens to Kirby Nazis to ghosts and mummies, yet in a truly effective, dramatic, and disturbing way. Like the kicker of

The Black Flame, when the industrialist who thought he controlled the frogs, his former lab experiments, gets dragged underground to burn forever as a beacon to attract their Lovecraftian space lord -- and Liz lets it happen because he killed her friend. It's one of the creepiest moments for me ever in comics. Going back to Jack Kirby for a minute: I told him, in a way I

thought was flattering, that his Thor meets Pluto issue so scared me as a 7-year-old that I had to put the comic down and wait a day to finish it. He got quiet, contrite, and said, "I'm sorry." The

BPRD crew owes me several of those Kirby-sized apologies.

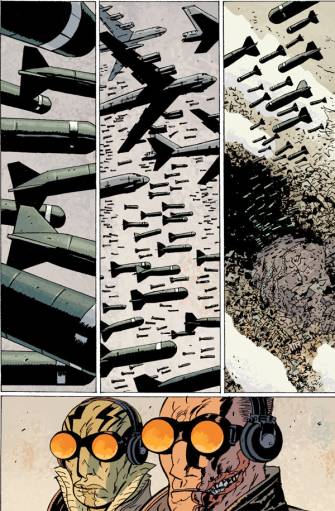

Design comes to mind, too. Mignola says in one of the introductions that Guy Davis is one of the best "creature guys in the business." So true.

BPRD feels so unique from the creators previous work that you can't do a fan's Who Did What analyses of it, but Davis' creatures, the crazy looks of the technologies, and the dense but not detailed look of his stuff -- not sure if that's the best way to put it -– is a great look. Davis' Jules Verne containment suits for the Oannes Society in

Garden of Souls and how he composes panels in

The Black Flame. He does grimy well, too.

Paul Azaceta did an amazing job with the Vampir Sturm technology, the gestation tubes, period Berlin, the creepiness of the Soviet demon, and even made photo reference art work for me.

SPURGEON: Is there something to be said for the serial aspects of the experience of reading

SPURGEON: Is there something to be said for the serial aspects of the experience of reading BPRD

? Has it been fun to move from book to book? Is that an experience we've seen less of in a decade that emphasizes the complete novel held in one's hands? Is comics giving up something important if they move even further away from serial entertainment?

SCHWARTZ: Well, I've noticed that in the weaker storylines (and none are that bad), it's better to buy it monthly so that what works holds you in suspense for months before it comes crashing down. I tend to reread good issues while waiting for the next issue, whereas I read collections once and move on. Otherwise, no, either way is fine, although I prefer to have a bound story on my shelf than five loose comics to store.

SPURGEON: They've had a remarkably consistent run with the creators on those books. Guy Davis is a very stylish artist in his own right: what is your estimation of his work on this series? What does he do that Mignola doesn't when working this approximate style?

SPURGEON: They've had a remarkably consistent run with the creators on those books. Guy Davis is a very stylish artist in his own right: what is your estimation of his work on this series? What does he do that Mignola doesn't when working this approximate style?

SCHWARTZ: Yeah, if they quit today the

Hellboy through

BPRD years can match any great run at Marvel,

Fawcett, anywhere. Every issue is gravy from here on, I guess. As I mentioned above, Davis is a great designer of creatures and stuff for comics. He appears to be a researcher who adapts styles and periods into his own. Davis' work has a proximity to Mignola's core look without being derivative in any way: blocky, inky, dense and cartoony. He can choreograph action sequences or conversations equally well, and has a gift for the disgusting (bones from rotted flesh, the giant tadpoles). Davis gets story down. He doesn't appear challenged by simple character moments anymore than conceiving of antebellum fishman romances. A rare talent.

SPURGEON: I take it from what you wrote me that you consider these more or less superhero books, but do they have other genre elements? Do they continue the Hellboy tradition of horror and horror imagery? What is it about the superhero model that makes it so easy to graft on these various out-of-genre elements?

SPURGEON: I take it from what you wrote me that you consider these more or less superhero books, but do they have other genre elements? Do they continue the Hellboy tradition of horror and horror imagery? What is it about the superhero model that makes it so easy to graft on these various out-of-genre elements?

SCHWARTZ: As far as extending the original series' interest in horror -- both series actually do it simultaneously. So yes. The addition of

Richard Corben to the

Hellboy books is a good one, and it's all expanding one large canvas. Actually, I'd say they're better at reinventing horror's character and spirit. Lots of people draw horrific stuff, but this creative team does it through the writing, too, which is rare in comics. Given that, I'm guessing it gives Mignola, Davis, Azaceta, Nowlan, and Corben's work that much more impact.

But yeah, it's essentially a superhero book: the characters have superpowers, there's super-villains, a super-cool HQ, plus, in

BPRD, the characters ride in helicopters (or other cool vehicles) to fights. So, yes, it's a superhero book.

BPRD has the classic line-up: strong guy, smart guy, alien guy, and underestimated but super-powerful girl (like

Sue Storm,

Jean Gray/Phoenix). Also, there's only

one woman, so you know it's a superhero team.

BPRD is a superhero book for me like Moore and Nowlan's

League Of Extraordinary Gentleman is a superhero book. What's cool about

BRPD and

LOEG is applying one genre's conventions in new contexts outside the Golden Age masked mystery man model. It's fun because they aren't constrained by either genre they use. In Moore's case, his "grand unification theory of fiction" idea is a little distracting, like his attempts at politics in

Watchmen. I liked it when it was Victorian England, where

Wells, Verne,

Burroughs, and

Stevenson all made sense together. Mignola does that a bit by allowing

BPRD to explore any supernatural world, from Lovecraft to

Stoker to

Rohmer to the Bible, and then mix in historical figures like Rasputin and Hitler. In pulling

Brecht and

Woolf into

LOEG, Moore dumbs down some great stuff if you've read it or seen it performed well. On the other hand, he elevates the pulp stuff he touches. I mean, while the rest of the literate comics world turns to the self-contained "novel" model, Moore moves in the opposite direction, obliterating distinct literary works into one Stan Lee-like Mighty Moore "universe." The current "

1910" has characters like

Mack the Knife and Jenny Diver from

Three Penny Opera, but singing lyrics in comics; that's pretty much the province of

MAD magazine. Then again, if you haven't read Brecht and Woolf, who cares? The

LOEG Andy Capp cameo, however, is great. I hope we'll see Andy meet Orlando in a pub soon. Andy can sing the Kinks'

Lola.

SPURGEON: Do you think they'll still be doing this series this way in five years' time? Ten? Would you follow it if they went to serializing the work on-line? As someone who's done so much work in several media, what do you think about the death of print vis-a-vis the fate of comics?

SPURGEON: Do you think they'll still be doing this series this way in five years' time? Ten? Would you follow it if they went to serializing the work on-line? As someone who's done so much work in several media, what do you think about the death of print vis-a-vis the fate of comics?

SCHWARTZ: I don't know. Mignola's already moved into film, animation, and novels, and none of that has taken the creative lead from his comics the way movies did

Iron Man and

Batman. I'll go where the best story is, I guess.

Honestly, I don't read that many comics on-line. I'm at

Meltdown every Wednesday with

Brian Doherty and

Joe Matt. However, I can easily see the Internet as animation or film platform for comics. Do superheroes even need comics anymore? I like the superhero movies, cartoons, and toys better than the comics. Most kids will discover Superman as my son has, not in a comic book. The comics form might be too limiting for the superhero of the future and what new audiences out there want from them. If it wasn't for

BPRD and

LOEG, I'd say that was true for me.

SPURGEON: Finally, you edited a forthcoming anthology of critical writing about comics for Fantagraphics. Can you talk about that process a bit? Was it easier or more difficult than you thought to find pieces good enough to go into such a collection? How much of the work came from on-line sources? Do you have favorite writers about comics on-line?

SPURGEON: Finally, you edited a forthcoming anthology of critical writing about comics for Fantagraphics. Can you talk about that process a bit? Was it easier or more difficult than you thought to find pieces good enough to go into such a collection? How much of the work came from on-line sources? Do you have favorite writers about comics on-line?

SCHWARTZ: You know, when I first pitched the book to

Gary Groth, he sent me back an e-mail asking me if I really felt I could fill a whole book with good comics criticism and attached his essay, "The Death of Criticism." I have the advantage of selecting criticism from 2000-2008. In that period

The New York Times,

Bookforum,

Comic Art,

The Comics Journal, and newspapers and magazines around the country were all running comics reviews, interviews, and feature pieces. There were also groundbreaking histories of comics published, as well as some cartooning that was critical in nature. So, no, I did not have a big problem finding stuff. My main consideration in choosing pieces was: does the writer's piece fit the book's main editorial guideline, that it somehow is about the literary comics movement or somehow influencing that movement? That alone cuts out a lot of good writing simply by subject, like almost all superhero stuff (except for an awesome Ditko section). The second issue was the time frame. I specifically set the date of September 12, 2000 as the start point, which is the day both

Jimmy Corrigan and

David Boring were released by

Pantheon, the date

Rick Moody (one of our contributors) describes as when comics were "unavoidable" in literary conversation. That's a tipping point moment for comics, and I wanted the anthology to cover that moment onward.

My only real headache was finding enough stuff not yet published on-line so that readers wouldn't look at our table of contents and ask, "Why buy this when I can google it all at home?" As for on-line favorites, if you mean writers who write exclusively on-line about comics, well, not many are exclusive. Several writers from

Comics Comics are in the book, a piece from

The Two-Fisted Man, and

Paul Gravett, all come to mind. Several pieces, say by Chris Ware or

Ken Parille or

Sarah Boxer, have been updated and revised from their on-line presences. Through our different contributors, the book is meant (as best I could) to sketch out the major developments and artists of the period. A couple of writers I did not get into the book would be

Jog the Blog or

Tim Hodler.

Todd Hignite is planning a

Comic Art anthology at some point, so I was limited in pieces from his great magazine. Also, there's going to be some major works skipped over because they did not get a great piece written about them no matter how good the book is, so I admit the editing is imperfect in that sense. The pieces had to be really good and about a specific comics area, the lit comics or "graphic novel" area.

That's why

BPRD is such a big deal for me (personally, anyway). That after 20 years or so, I'm finally totally into a genre book that doesn't need any apologies.

*****

*

B.P.R.D. Volume 1: Hollow Earth and Other Stories, Mike Mignola and Chris Golden and Tom Sniegoski and Ryan Sook and Brian McDonald and Derek Thompson, Dark Horse, softcover, 120 pages, 9781569718629, January 2003, $17.95

*

B.P.R.D. Volume 2: The Soul of Venice and Other Stories, Mike Mignola and Miles Gunther and Michael Avon Oeming and Brian Augustyn and Guy Davis and Geoff Johns and Sott Kolins and Joe Harris and Adam Pollina and Cameron Stewart, Dark Horse, softcover, 128 pages, 9781593071325, August 2004, $17.95

*

B.P.R.D. Volume 3: A Plague of Frogs, Mike Mignola and Guy Davis and Dave Stewart and Lia Ribacchi, Dark Horse, softcover, 144 pages, 9781593072889, February 2005, $17.95

*

B.P.R.D. Volume 4: The Dead, Mike Mignola and John Arcudi and Guy Davis and Dave Stewart, Dark Horse, softcover, 152 pages, 9781593073800, September 2005, $17.95

*

B.P.R.D. Volume 5: The Black Flame, Mike Mignola and John Arcudi and Guy Davis and Dave Stewart, Dark Horse, softcover, 168 pages, 9781593075507, July 2006, $17.95

*

B.P.R.D. Volume 6: The Universal Machine, Mike Mignola and John Arcudi and Guy Davis and John K and Dave Stewart, Dark Horse, softcover, 144 pages, 9781593077105, January 2007, $17.95

*

B.P.R.D. Volume 7: The Garden of Souls, Mike Mignola and John Arcudi and Guy Davis and Dave Stewart, Dark Horse, softcover, 146 pages, 9781593078829, January 2008, $17.95

*

B.P.R.D. Volume 8: Killing Ground, Mike Mignola and John Arcudi and Guy Davis and Dave Stewart, Dark Horse, softcover, 140 pages, 9781593079567, May 2008, $17.99

*

B.P.R.D. Volume 9: 1946, Mike Mignola and Joshua Dysart and Paul Azaceta and Nick Filardi, Dark Horse, softcover, 144 pages, 9781595821911, November 2008, $17.95

*

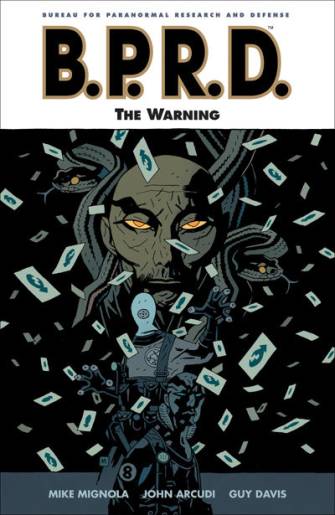

B.P.R.D. Volume 10: The Warning, Mike Mignola and John Arcudi and Guy Davis and Dave Stewart, Dark Horse, softcover, 152 pages, 9781595823045, April 2009, $17.95

*

B.P.R.D. Volume 11: The Black Goddess, Mike Mignola and John Arcudi and Guy Davis and Dave Stewart, Dark Horse, softcover, 152 pages, 9781595824110, October 2009, $17.95

*****

This year's CR Holiday Interview Series features some of the best writers about comics talking about emblematic -- by which we mean favorite, representative or just plain great -- books from the ten-year period 2000-2009. The writer provides a short list of books, comics or series they believe qualify; I pick one from their list that sounds interesting to me and we talk about it. It's been a long, rough and fascinating decade. Our hope is that this series will entertain from interview to interview but also remind all of us what a remarkable time it has been and continues to be for comics as an art form. We wish you the happiest of holidays no matter how you worship or choose not to. Thank you so much for reading

The Comics Reporter.

*

CR Holiday Interview One: Sean T. Collins On Blankets

*

CR Holiday Interview Two: Frank Santoro On Multiforce

*

CR Holiday Interview Three: Bart Beaty On Persepolis

*

CR Holiday Interview Four: Kristy Valenti On So Many Splendid Sundays

*

CR Holiday Interview Five: Shaenon Garrity On Achewood

*

CR Holiday Interview Six: Christopher Allen On Powers

*

CR Holiday Interview Seven: David P. Welsh On MW

*

CR Holiday Interview Eight: Robert Clough On ACME Novelty Library #19

*

CR Holiday Interview Nine: Jeet Heer On Louis Riel

*

CR Holiday Interview Ten: Chris Mautner On The Scott Pilgrim Series

*

CR Holiday Interview Eleven: Tim Hodler On In The Shadow Of No Towers

*

CR Holiday Interview Twelve: Noah Berlatsky On The Elephant And Piggie Series

*

CR Holiday Interview Thirteen: Tucker Stone On Ganges

*

CR Holiday Interview Fourteen: Douglas Wolk On The Invincible Iron Man: World's Most Wanted

*

CR Holiday Interview Fifteen: Jog On Death Note

*****

*****

*****