Home > CR Interviews

Home > CR Interviews CR Sunday Interview: Ian Boothby

posted June 27, 2010

CR Sunday Interview: Ian Boothby

posted June 27, 2010

*****

_thumb.jpg)

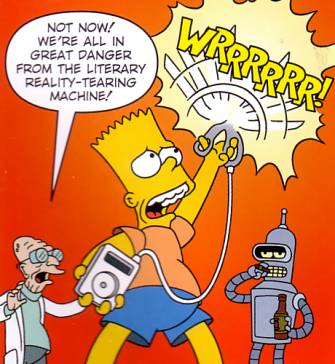

I first became aware of

Ian Boothby as one of the talented wave of Vancouver mini-comics creators that sprung up in the mid-1990s, a group that for its proximity to a few prolific

Comics Journal contributors of the era had their work reviewed in the magazine. Fast-forward a decade or so later and I discovered that Boothby was one of the writers at

Bongo responsible for their

Simpsons comics, a fine place for someone with his combination of television and comics writing experience. I'd read a few Boothby Bongo efforts over the years since, but had my first prolonged exposure to that work through

Abrams' collection of his

Simpsons/

Futurama comics in a handsome slipcase called

The Simpsons Futurama Crossover Crisis. I enjoyed reading the comics, I liked Boothby's writing in them and I thought they exhibited different qualities than most comics have these days -- all of which added up to something worth talking about. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: When I was doing my research, one thing I thought would be easy is figuring out your comics career, how you started doing comics in a way that led you to where you are now. But actually, I still have no idea how you started writing comics. I know you were doing mini-comics in the 1990s. Is there an easy way to describe how you went from there to working for Bongo?

IAN BOOTHBY: I went to the first

Alternative Press Expo, I believe it was San Jose. I was selling my mini-comics there. I ran into

Terry Delegeane and

Scott M. Gimple. Bongo was fairly new out of the gate. I was handing out my minis to whoever was there. I didn't want to carry them home with me; I shouldn't have crossed the border with them. I already had the border guards basically try to kick me back home when I was going down, so I didn't want to carry them back with me. I gave them a couple of the comics and asked if they were taking submissions, and at that time they were. They got back to me really quick. Said, "We love these, these are great, we'd love to have you do something." About three years later they got around to it. [laughs] Very slow, slow, slow, slow process.

SPURGEON: I remembering enjoying your mini-comics, but I don't remember them being like the material you're doing now. They were well written and accomplished in a way they'd be a nice showcase for you, but was getting work writing comics the goal of doing the minis?

BOOTHBY: Oh, no. No. At that time I was just coming off of working on a television series. When I was 14 I became the youngest writer, the youngest union writer in Canada for TV. I was working on a show called

Switchback for the

CBC, writing sketches and performing in them. When that kind of wrapped up, I was at loose ends, and so decided to make my own stuff. I was creating plays and that kind of thing as well. I was also doing some stand-up. But yeah,

Kinko's just started being in our area, so you could actually Xerox stuff on the cheap. I got my stuff into local comic book stores and record stores.

SPURGEON: You're one of the few guys in comics I know where I bet in an article somewhere you've been described as a funnyman, [Boothby laughs] by which I mean you have this nicely rounded resume and these different creative experiences. Do you have a sense of how you might write comics differently for your specific career path?

SPURGEON: You're one of the few guys in comics I know where I bet in an article somewhere you've been described as a funnyman, [Boothby laughs] by which I mean you have this nicely rounded resume and these different creative experiences. Do you have a sense of how you might write comics differently for your specific career path?

BOOTHBY: I also have an improv background, and I think that's really where it comes from. I listen quite well to people's voices. And in improv, the idea is to make the other person look good. To make the other person look good, you have to know their voice. So I'm really good on picking up people's voice and character voices. So when you got a show like

The Simpsons, which has so many distinct voices, I'm pretty good at writing in a character's voice. So even if you don't necessarily like the joke that I'm putting down, it does sound like the person. That's a bit of an advantage.

It's a disadvantage to me reading comics, because if I read a typical DC comic, I'm one of those guys going, "

Lex Luthor would never say that." Because I'm pretty good at picking up a character's sound, whether I'm reading it or hearing it. It's served me pretty well in doing some animated series in the past. I'm pretty good at that sort of thing.

SPURGEON: Is there a specific school or approach to improv that you come from, or does the improv world even break down that cleanly? Is there a Del Close school... ?

BOOTHBY: People like to break it down into short form and long form. Games is the short form. Long form is something along the lines of what Del Close created called

the Harold. But I've been doing this for so long, and the people have been doing it so long with me, that we've made our own mishmash and pulled the elements that we like from both forms together and just do our own thing now.

On my blog I have a series of essays on improv and my problems with the Del Close and

Keith Johnstone methods. On Facebook they're on a group called "No And..."

SPURGEON: It says in the Abrams hardcover that this was your pitch, that it was your idea to do the crossover saga. Is that true? Did it start with you?

BOOTHBY: Yeah. I was writing most of the

Simpsons comic books at the time, and they had just come out with a

Futurama comic. I wanted to do some work on that, but they already had writers, primarily from the TV show, working on it. So I couldn't break into that book. I thought the obvious thing was to have a crossover between

The Simpsons and

Futurama [Spurgeon laughs]. Since I'm already doing this book, I can show them I can write these other characters. Matt wasn't game for that at first. He had kind of a worry that they'd crossover in a kind of "

Flintstones and Jetsons" bit of business. Also, it didn't make any sense. They were in different universes. I found a way of pulling that off. Bill Morrison -- my editor -- really liked it, ran it by Matt, he was game, and we went and we did it.

SPURGEON: I don't know anything about Bongo other than a bit about Bill Morrison and then a bit of familiarity with some of the creative people that have been involved over the years. It has a reputation as a nice place to work, a professional place to work. You hear from the occasional creator going, "That was a good experience." And I've not heard any corresponding grind

SPURGEON: I don't know anything about Bongo other than a bit about Bill Morrison and then a bit of familiarity with some of the creative people that have been involved over the years. It has a reputation as a nice place to work, a professional place to work. You hear from the occasional creator going, "That was a good experience." And I've not heard any corresponding grind against

Bongo. Is Bongo a supportive place to work? Are you encouraged to make pitches like your crossover idea? I guess I'm just asking if it's a good place to work.

BOOTHBY: Yes, it's definitely a good place to work. You'll hear repeatedly from people that the folks from Bongo are nice. The reason for that is they know what they're doing. [Spurgeon laughs] You find out in television that when people are assholes is because they're freaking out because they fucked up. And the thing is, Bill Morrison was the art director for

Futurama; he knows

Futurama, Terry Delegeane knows

The Simpsons. They all know what they're doing over there and they do what they do very well. Matt Groening is the boss. They report to him. He keeps things on track. He's hands-off, but when it comes to something big he gives it the yay or the nay. These are his babies. So they're very, very good at what they do, and because of that they have the freedom to be nice. They're confident and they enjoy what they're doing. That makes for a very good environment.

When you're starting off at Bongo -- and I was talking to another person who worked there: we both had the situation where you get a lot of notes off the top. You get lots and lots of notes. As time progresses, and they realize what you can do, you get next to none. That's the situation I'm sort of in right now. As for are they open to new ideas? Yes, they are. They're all very creative people, they all love comics, they all love the history of comics as well. So you get a book like

Radioactive Man, which may not sell really well, but it's really clever. It's doing parodies of things that you're going, "What? That? From that one '50s comic... you're making fun of that? You're spending this much of an issue on that?" It's just because they love the medium. That comes through in the books

and in the work environment.

SPURGEON: Do you have a sense of your audience for the original comic books? When you were doing these crossovers, were you hearing back from people? Is it different audience than the other companies out there have?

BOOTHBY: Yeah. It's a mainstream audience. [Spurgeon laughs] And that's how it's different. We've been lucky enough to have been flown all over the world. We've been to Spain, Germany. I've done signings in England. People love

The Simpsons. So they're approaching it, one, with that. They love those characters. So you're already a little bit of the way there. With most mainstream comics now, I think what's been happening is that it's getting too insider baseball. Their big events currently are bringing back characters that if you haven't been reading comics for 20 years you wouldn't give a damn about. Like

Hawk? What are you talking about?

But

The Simpsons, people know. They like them. And so you have a nice playing field to tell a story. Often I'll get the people who were dragged to a comic-con; they didn't necessarily want to come. But this is something they like. I'll give them a book or something and they'll dig it. Also kids go nuts for it as well. It's one of the few legitimate all-ages comics. Not the all-ages where it's just for kids. It's the all-ages hopefully like

Pixar where it's

actually all-ages.

SPURGEON: I'm trying to figure out where the comics exist in the constellation of Simpsons fans. Certainly not all Simpsons fans read the comics, so I was wondering what subset of Simpsons fans you think you're getting?

SPURGEON: I'm trying to figure out where the comics exist in the constellation of Simpsons fans. Certainly not all Simpsons fans read the comics, so I was wondering what subset of Simpsons fans you think you're getting?

BOOTHBY: Well, the

Simpsons audience is so huge that you only get a miniscule portion of them. The books don't sell particularly well in the Direct Market. But they sell really well on the newsstand. It's very similar to Archie in that way. If you saw the sales of

Archie in comics stores, Archie's not doing that well. But all these people know Archie, all these people read Archie. That's the same boat we're in. If you look at us over here, oh, not doing so well; if you look at us over here, we're doing very well. Whenever they have a free comic book day the Bongo stuff flies off the shelves. The people bring such a love for

The Simpsons to the book, when they know about it, it's like "Oh -- yoink!"

SPURGEON: I've read Bongo books here and there but to read a whole bunch of once, one thing that stood out for me is that it seems like you're not afraid of dialogue in these comics. There can be chunks of comedic dialogue. You're not whipping people through the comics with a cinematic approach designed to make the eye skim across the page.

BOOTHBY: Marvel loves splash pages, yeah.

SPURGEON: You're not afraid of telling a joke that way; you're not afraid of having 50-75 words on a page or making someone read 15 words to get to the funny part of the word balloon.

BOOTHBY: I do try to throw the visual in there, but

The Simpsons at its beginnings was a limited-animation situation. It was on

The Tracey Ullman Show,

Matt Groening was animating it, and he didn't have a lot of animation skills -- or the drawing skills, to be honest. But he did have the dialogue skills. That was the start of

The Simpsons. It was always dialogue-heavy. You never watched

The Simpsons and went, "Whoo, look at that art!" The comedy came from the dialogue. You'd get a few visual gags, but the dialogue carried it. I think a lot of

Simpsons episodes you could run on the radio and not miss too much.

It did become a thing where they'd throw a lot of gags into the background. We still try to do that: we put funny signs up, and if you have a store name or a mall, you want to fill it with as much stuff as possible. It's a little harder to do in a comic where you have a seven-panel page; you can only jam so much in there and have the reader be able to pick it up. You gotta choose your battles, and what I pick is dialogue over the visuals. Also, I have lot more control over dialogue. I don't know what the artist might do.

SPURGEON: Taking something from animated form and putting it into comics form, is there anything harder to do on the comics page? Is there an effect you lose that's harder to replicate than others?

SPURGEON: Taking something from animated form and putting it into comics form, is there anything harder to do on the comics page? Is there an effect you lose that's harder to replicate than others?

BOOTHBY: Yeah, you lose the voices. And the voices are hilarious. You lose the nuance of the voices. People do have

Homer's voice in their head when they read the dialogue. But there might be a little pause, or a going up: they're such skilled vocal artists. You do lose that when you put it into comic book form. Something like a pause: you might do a panel where someone is just staring at another person, play that beat out. They're totally different media.

SPURGEON: So you find ways to compensate.

BOOTHBY: So much of delivering a joke is the pacing. When a new writer comes into Bongo, quite often the mistake they make is they make things -- you were saying things were dialogue heavy -- they make things

too dialogue heavy. They don't give any room to breathe. They try to jam as much as they can in, and in doing so you lose the pacing of the joke. At some point you need to pull back a little bit, relax a little bit, and give the joke enough set-up.

One of the most frustrating notes I get not from Bongo but when I work in television is you write a comedy piece and they will like the piece but then go, "But this part doesn't get enough laughs."

So you go, "Well, that's the set-up."

"Can you throw a joke in there?"

"Not without ruining the punch-line." Because you're now not setting the stage for what comes later. I think that's something that new writers do: they try and jam so much in there, make it so dense, that you don't really give people a chance to relax. You need to a little bit of space in structuring a joke or, really, any kind of dialogue.

SPURGEON: I was impressed with the number of visual gags that were in these comics and the way that many of them were seemingly for texture, say, and not necessarily germane to the plot. There are a number of science fiction parodies later on that flash by really quickly; there's a scene early on where something drops through the various levels of reality all the way to Hell.

BOOTHBY: That wasn't in the original. That's from the two pages of bonus material that you get in the book.

SPURGEON: Do you have to be aware of making sure that's there enough funny business going on? It almost seems like a texture or tone issue, where you have a certain number of gags that stand apart from helping move things along. I assume you write all of those, because they seem too specific to develop organically.

SPURGEON: Do you have to be aware of making sure that's there enough funny business going on? It almost seems like a texture or tone issue, where you have a certain number of gags that stand apart from helping move things along. I assume you write all of those, because they seem too specific to develop organically.

BOOTHBY: Yeah.

SPURGEON: So is there a way you pace yourselves with such sequences?

BOOTHBY: How I write is I'll write an outline that gets approved by Bongo. I'll draw the comic out myself with very rough figures. I'll then read it over and see what's missing. If there's a page where I go, "There's no jokes on this page; this just pushes the plot along." Then I gotta gag up that page. If a page is

just jokes, and doesn't move the story along, then I have to throw a little story in there. I'll also look to throw in heart, emotional beats. It all becomes a real balancing act. If I just wrote it in straight script form, I don't think I'd be able to do that. But when I sort of create the comic first myself and flip through it, I can see what's missing and what's needed.

Of course, when you mention that page where the poo falls through the floor to hell and hits Stalin on the head [Spurgeon laughs] you couldn't really do that in television. You could have a pan down, but it works best in comics because panels in comics also look like floors and you could pull that off. There are things you can do in comics that you can't do in the television series. I try to think of what can't they do. An example of that would be earlier on in the comic where we have a

Charles Atlas parody. Those have been done a lot, but it's something where if you did it on television it wouldn't have the same impact than doing it in a comic where that kind of thing originated.

When I talked to

David X. Cohen, one of the co-creators of

Futurama, he said that was the page where he started to like the book. I think that's the page where it becomes its own thing. This is why we're doing this as a comic; you can do

this.

SPURGEON: As the writer that mashed the two universes together, is there anything about doing so that surprised you? For instance, as might be expected you paired off a lot of the characters for different scenes; is there an effective pairing that you didn't see going in?

SPURGEON: As the writer that mashed the two universes together, is there anything about doing so that surprised you? For instance, as might be expected you paired off a lot of the characters for different scenes; is there an effective pairing that you didn't see going in?

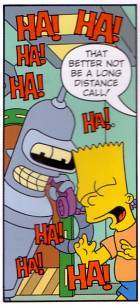

BOOTHBY: When I got into the second series, I thought we had pretty much done the major matches with people. But then you go, "What do I do with

Moe?" And you go, "Oh, they do have that bartender that looks like

Isaac from The Love Beat." And then it's like, "If they're doing that, there should be a crank call, and it should come from both

Bender and

Bart..." I'd say the characters write themselves, but I still want to get paid. [Spurgeon laughs]

It's basically like when I was a kid and I read

Superman Vs. The Amazing Spider-Man. I still have that comic here in the office. It's one of my favorite comics. It was such a kick to go, "Yeah, that's right,

Clark Kent and

Peter Parker do have similarities." But you get to see the differences as well:

Perry White is a great guy compared to

J. Jonah Jameson. When I was doing this book, my guide was to make it as cool as

Superman Vs. The Amazing Spider-Man was for me.

SPURGEON: Did you contribute directly to this current hardcover, slip-cased collection? Did Abrams' interest in these comics come as a surprise?

BOOTHBY: James Lloyd and I both supplied some extra material for the book. One of the things that didn't end up making it in there was I had some script for the comic and some commentary on it as

Harold Zoid,

Zoidberg's uncle. That didn't make it in there. We put in a couple of extra pages, like the one where Stalin gets hit on the head. But aside from that? No, not much. We're both pleasantly surprised at how it turned out.

SPURGEON: Are you getting a different audience than you do with the serial comic, do you think? Because I'm not sure I would have read these comics in any other format.

BOOTHBY: It's selling quite well. It's the kind of thing that if you're in a bookstore, and I see them in basically every bookstore around here, you put it in a fairly prominent place. It leads you to look at other books. People like

The Simpsons and

Futurama. It might get picked up by people who wouldn't buy the softcover Harper-Collins trades. The

Wall Street Journal list of Best Selling Graphic Novels had it in the #2 position just below

Kick Ass. It's currently #3.

SPURGEON: Ian, you're still a comics reader, aren't you?

SPURGEON: Ian, you're still a comics reader, aren't you?

BOOTHBY: Yes, I am.

SPURGEON: Some of your comments earlier made me realize you're working out of a different comics culture than general comics culture. You also have a perspective you bring from other entertainment fields. I wondered if you had anything to say on how things are going in comics generally. It occurs to me it's an entirely different field than it was when you were doing your mini-comics and I was reading them. Are you a happy comics reader, Ian?

BOOTHBY: [laughs] I'm not necessarily -- no, I'm not a happy comics reader. [Spurgeon laughs] I don't read

Spider-Man anymore, because some major mistakes have been made to that character. I'm hardly the only person saying that. But what I used to like about Spider-Man was that he was the character that stuff happened to and then he moved forward. Superman stuff happened to, but nothing stuck to the guy. Spider-Man was the guy whose

main villain killed

his girlfriend and they both stayed dead. Can you imagine

Lois Lane being killed by Lex Luthor? That's what made Spider-Man different. He was a working class hero. If he and

Johnny Storm walked out of a building, Johnny would see an alien attack, Spider-Man would see a mugging or an animal-themed villain robbing a bank. That's who Spider-Man was.

Somehow along the way they decided to give him

a satanic divorce. [laughter] They decided, "You know what Spider-Man is? He's young. And people need him to be young." And that's a mistake because Spider-Man's main theme is responsibility. If your character's main theme is responsibility, as a writer you want to give him as much responsibility as possible. He was going to have a baby once, and they just made that baby disappear. I know there's a worry where there's a point where you never get them back. But any responsibility you give to the guy should work.

Spider-Man was a role model for me and your role model shouldn't be making deals with the Devil. Don't worry about taking responsibility for your actions kids, your problems will magically go away eventually.

They've lost the mission statement of the character. Nothing can really happen that'll have any effect and so the heart of the book has been torn out. The stories might be clever but that's all they can be. And that's a real loss.

It seems like right now, Marvel and DC have lost their balls. They make big decisions, they kill a bunch of characters, they rape a bunch of characters, and then they do pullbacks on everything. They bring those characters back, or they won't take responsibility for what they've done. It's just shock, shock, shock. And in doing so you lose your mainstream audience. Completely. You lose your new readers. I love comics. I have some friends with children that are 11 and 12, and I can't give these comics to them because

Dr. Light is raping people. It's horrible, gory, shock stuff. The kind of stuff you'd see in Vertigo ten years ago is mainstream now. And where are you going to go from there?

SPURGEON: It occurred to me that The Simpsons

has been on the air for about as long as Marvel's superhero universe had been around by the time they started doing things like Contest Of Champions and Secret Wars. Is there something to be said for the difficulty of managing an interconnected property when it gets to be that age?

BOOTHBY:

BOOTHBY: For most people,

Spider-Man will be the movies. More people will see the movies than will ever read a comic. More people will see the image on the t-shirt than will see the comic. Same with

The Simpsons: more people will see the television show or the movie or the images on the lunchboxes. So I can't make the comic book too inside. I'm reminded there's a mainstream audience I should be serving, and I think that's what mainstream comic books have lost. They're tending to people that are already in the clubhouse. The

only thing that can happen is that the audience will shrink. There's no way for it to expand.

One thing I think might save comics -- and again I'm not the only person saying this -- is something like the iPads and what have you. Because people love comics. They're nuts for comics. You give a good books to someone and they're crazy for it. Like

my wife's comic

Y: The Last Man. People who've never read comics love that one. They have no beef with the medium; it's just the continuity that holds them back. When you have something like the iPad, you can see any comic that's been done in history. You don't need to know what's going on now. You can read a great arc of

Spider-Man, or

The Simpsons, or

Little Lulu or

Wonder Woman. I think one of the things that will save comics is ditching the continuity and relying on the huge library we now have access to of all the great stuff that's come before.

*****

*

The Simpsons Futurama Crossover Crisis, Matt Groening and Bill Morrison and Ian Boothby and James Lloyd and Steve Steere Jr., Abrams, slip-cased hardcover, 208 pages, 0810988372, 9780810988378, April 2010, $24.95

*****

*****