Home > CR Interviews

Home > CR Interviews CR Holiday Interview #9—Jason T. Miles

posted January 10, 2011

CR Holiday Interview #9—Jason T. Miles

posted January 10, 2011

*****

I wanted to interview the cartoonist, 'zine distributor and alt-publisher employee

Jason T. Miles for reasons having to do with each of the hats he wears, but I'll admit that my primary motivation was a conversation at

San Diego we had about his switching jobs at foundational alt-comics publisher

Fantagraphics. It was the kind of chat that I have with a lot of my friends, but rarely with those in comics: the excitement of taking on new responsibilities, the possibilities for certain skills to be applied. My friends in comics either don't stay around for very long, period, or dig in at one job for what seems like forever. I've been more and more convinced in recent years that one of the reasons the non-Big Two companies have been able to find a bigger place for themselves in the industry is that they've managed to hang onto more employees -- employees like Miles -- for a longer period of time. Miles is also a compelling cartoonist, working in a number of self-published formats and most memorably with

Zak Sally of

La Mano 21 on

Dead Ringer. Owning and operating a 'zine distribution company, as is the case with Miles'

Profanity Hill, intrigues me because of the sea change in that area of expression since the photocopy-happy 1990s. In other words, there's a lot to discuss. The following interview was conducted via e-mail and edited for clarity and flow by me. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: One of the things about which I'm talking to a lot of people this year is jobs, and you switched yours this year. Can you talk about what it is you're doing for Fantagraphics now, what you were doing, and what specifically appeals to you about your current duties?

JASON T. MILES: I was the "Director of Sales" for Fantagraphics for about three years and I worked in the warehouse for about four years prior to that. As the "Director of Sales" my primary functions were to process wholesale orders as well as drum up new wholesale business. In effect my job was to facilitate the movement of books from point A to point B and then payment from point B to point A in an efficient and sometimes creative way. A lot changed during my time in the position... in fact the job title is now "Inventory Manager."

My current job title is "Operations/Editorial" and I see my current position as an opportunity to utilize all of my experience in the publishing industry to assist just about every factor involved in making or attempting to make great books. I especially enjoy watching a book take shape from catalog copy to finished product... it's almost always a strange and surprising journey!

Back when I was working at the warehouse I was just working there... it was a cool place to work and I didn't have to sit in front of a computer all day and it helped pay the bills while I toiled away making art... and then the "Director of Sales" position opened and I thought, "Aw, hell..." I'd never tried to work towards the center of a company. I'd always just worked to pay bills and subsidize my non-working life... so here's this opportunity and... working joe jobs is easy, you put your time in and you go home... and I'd built this idea that the ease of joe job made it so I still had energy to make art, so I'd been nervous about working my up the ladder so to speak because I thought my art making practice would suffer, and I must admit I was nervous about being turned down... but I went for it because I love comics and making books and since I'd never tried working my way up the ladder, what did I know about how it was or was not going to go? And I got the job! I interviewed for it with

Gary [Groth] and got it. I remember right away both

Eric [Reynolds] and

Jacob [Covey] were worried I was going to stop making art and I guess I'm proud to say I'm now making more art than ever before.

SPURGEON: What is your work day like? What are the nuts and bolts duties of your job? We know almost nothing about editors at these smaller companies because until recently companies of that size didn't really have a lot of people primarily devoted to working on the production side of things.

MILES: Lately, I've been getting to the office around noon and staying until 8 PM. When I first come into the office I turn on my computer and open old-fashioned mail while watching my e-mail counter jump to anywhere from 35 to 85 new e-mails. The old-fashioned mail usually consists of printer proofs and book dummies as well as other stuff. I give the other stuff to other people and then go over the proofs and dummies to suss out any problems. If it's necessary, I'll discuss the proofs or dummies with Gary,

Kim [Thompson] or Eric or the designers in order to resolve any open issues on are end of production and then I'll contact the printers to let them know what needs to be changed or that everything looks great and to start the presses! By this time I've now got anywhere from 50 to 90 unread e-mails so I e-mail until lunch. I eat lunch while reading a couple of pages from a book or I skim web sites... I really hope people aren't finding this boring.

SPURGEON: [laughs] Most jobs are boring.

MILES: Lunch takes about 20 minutes to 30 minutes and I'm back at it, usually addressing the work generated by the pre-lunch emails until the end of the day. This work can consist of many different things including: talking with artists and editors about how their books are or are not taking shape, talking with Gary, Kim, Eric and the designers to see where their projects are at and what they need, running remainder sales with one or more of the various bargain book distributors, researching sales to help Gary or Kim set print runs, making bookplates for our mail order department, I might be working on putting together an art show for our bookstore/gallery, sending materials to authors and printers, running art and material by Disney and United Media for approval, advising on how to try and tackle a new found problem (there's a lot of this) etc. etc. etc.

SPURGEON: Now, was working for a publisher ever an ambition for you? What took you to Fantagraphics in the first place?

SPURGEON: Now, was working for a publisher ever an ambition for you? What took you to Fantagraphics in the first place?

MILES: I tried to get a job at Fantagraphics when I was 13 or 14 years old. One of my cousins had given me a stack of comics which included

Usagi Yojimbo,

Frank and

Love & Rockets. While reading these, I saw the address for the company was about seven miles from my house! It made my then cartooning aspirations seem possible. As a kid and into Junior High I made my own comics and books of drawings, so this is something I've always been excited about. So, I called Fantagraphics and asked them for a job interview... I literally had no idea what to expect... I had this fantasy that I would get an art job but was old enough and cynical enough -- this was the early 90's -- to know better, sorta.

The voice on the other end of the phone gave me a date and time to meet and a couple of days later my mom drove me to the Fantagraphics office. The house next to our office is owned by a really nice witch and she's covered her house with spells and art and it looks like no other house on the block and when I thought this was Fantagraphics I was very excited... but then we discovered it was the drab, gray house next door with busted up TV's and photocopiers in the yard. My mom and I knock on the door and someone yelled at us to come in, so we walk inside "... Hello?" and this guy is over in the corner and drunkenly yells "Oh shit! Hide the stuff! A kid's here!" My mom let out a nervous laugh (she's a school teacher) and someone asks why were there and I say, "I'm here for the interview" and the person laughs and says "Uhh... ok... follow me" and they take us to a fresh-faced Eric Reynolds! Eric gave us a tour of the house, which was a complete mess, I loved it, and then explained that I'm probably too young to work there because of the explicit material on hand -- Eros was in full schwing! sorry -- but if something comes up he'll call me. Of course he never called but the whole experience set me on fire and I went home and started my own comic book company and started drawing comics and enlisting my friends and... today I'm finally working for Fantagraphics and I'm still making and publishing my own comics.

SPURGEON: I'm not sure I know all that much about your general relationship to comics, but if we had met five or ten or 15 years ago would I have seen you reading comics? Or is comics something more contemporary for you?

MILES: My first remembered experience with comics was watching Saturday morning Spider-Man and Hulk cartoons. A little later on, I managed to cull together a small stack of comic books. My early years were in rural Wyoming so comics were not in abundance. My Grandma and Mom are artists so early on I cast off comics for fine art and spent a good part of my adolescence trying to draw from life. Summer after 3rd grade I discovered

Calvin & Hobbes and

The Far Side and I was back with the comics, drawing retarded

Garfield and

Lockhorns. Around 5th grade my awesome aunt gave me a subscription to

Mad Magazine. The first issue I received had

a cover spoofing the Garbage Pail Kids. I had no idea what Garbage Pail Kids were but the cover of this

Mad had Alfred E. Neuman puking on himself... haw! So I got heavily into

Mad, especially

Don Martin,

Al Jaffee and

Dave Berg. Nobody draws spite and disgust like Dave Berg. All of his characters look like they just stepped in dogshit. Unbelievable.

Eventually I got heavily into Garbage Pail Kids and the other great Topps card series and then

Superman died... and I got into superhero comics for about a year or two... until Batman died or

had his back broken which was very clearly a sales ploy on the part of DC which really pissed me off. By this time I was listening to grunge music and everyone in Seattle was sad or depressed or pissed off and cynical and pointing out how lame everything was... the mainstream telling the mainstream how lame being mainstream is... so I was bitter and stopped reading superhero comics just in time to get that stack of comics from my cousins and find

Love and Rockets and

Frank.

SPURGEON: Got it. So are the people who knew you back then surprised by what you're doing now?

MILES: I doubt people who knew me way back would be

that surprised by what I'm doing now. I'm probably more surprised than anyone else. Way back, I thought I was going to be making movies. I've always been into stuff like publishing. I worked on the high school paper not because I liked high school and had a jones to write and draw about it but because I wanted to learn how a paper was made. And working at Fantagraphics has been the best most practical experience I continue to have learning how to try make things. But it's different from making art even though art is part of the publishing process.

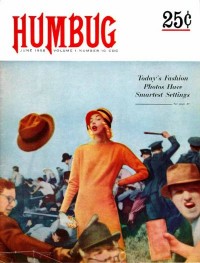

SPURGEON: Can you talk about working with the Humbug material as a cartoonist? You're in many ways a very different cartoonist than those men and working from a context divorced almost entirely from their commercial art world. How did you regard the material when you were holding it in your hands, living with it for a while? Did your perspective change on those comics while working with them?

SPURGEON: Can you talk about working with the Humbug material as a cartoonist? You're in many ways a very different cartoonist than those men and working from a context divorced almost entirely from their commercial art world. How did you regard the material when you were holding it in your hands, living with it for a while? Did your perspective change on those comics while working with them?

MILES: Working on

Humbug continues to be a huge influence on me. I learned a lot working on those books. We were very lucky to have a lot of the original artwork to shoot from and therefore I was able to live with a lot of amazing artwork which is not that common anymore thanks to the digital age. I had the opportunity to pore over a lot original artwork by the likes of

Will Elder, Al Jaffee and

Arnold Roth and what really left a lasting impression on me, personally, was how collaged there stuff is. Some of the Elder stuff was three or four different pieces of board patched together to make a single beautiful perfect image. This gave me license to loosen up with my stuff and not hesitate to cut it up or collage things into it, which is a lot of fun and feels totally appropriate to the nature of comics.

One day I was walking through the art department with a box of Will Elder originals and someone comes up to me and tells me Will Elder just passed away. That was something. He's one of my all time heroes -- my favorite artist -- and we were trying hard to get the book done so he could see it. I'll never forget that moment... I don't even know how to describe it.

SPURGEON: Sometimes I still find myself anticipating the Humbug

collection and I have to remind myself that not only did it come out, it was just about everything I expected it to be. Do you feel that projects like the Humbug

collection receive the attention they deserve on an individual basis considering this absolute flood of quality publishing right now? Is that an issue, do you think, that projects may not be getting their just due?

MILES: For as long as I've been following stuff like this -- since 1996 or so -- it's never been out of the realm for great work to go unnoticed and for lousy work to receive worship... and vice-versa. When it comes to this stuff, I guess I get frustrated the most by how we (as an industry or species, thanks to internet participation) can create a bullshit story around a book or author or publisher or perceived movement or trend. I mean, how do you measure the attention a book gets anymore? The next question of course should be, how do you measure a book's success? There are so many factors that go into a book's production and reception that I think we'd all be surprised by how a book is truly received, provided we could devise a universally accepted audit of the process.

SPURGEON: If I recall correctly, your first minis came out in about ten years ago. How long had you been making comics before that? What circumstances led you to self-publish your work? What was rewarding about it for you that kept you doing it?

MILES: Yeah, I started making zines in the late 90s and my first somewhat mature mini comic came out in 2003. All through Junior High and High School I tried making comics, to very little success. I'd usually get to the third panel or second page and just start drawing. I come from a very pragmatic family and I figured early on that if I was going to do something in art it would be as member of an assembly line -- something like a penciler or inker or animator or something like that -- and so I did a lot of just drawing through my teen years and by the time I went to college I was making videos and animation and still drawing but only reading comics.

The moment I finished college I immediately started drawing comics. I don't know why exactly but I did and thanks to being in a place like Olympia I knew I could publish my own comics and that by doing so didn't negate the validity of what I was doing in the face

Marvel or

DC or Fantagraphics. I'd been making zines and working at Kinko's. I knew how to paste up a 'zine, so I knew how to paste up a comic.

Around 2002, I was a big fan of

Highwater and I related to almost everything Tom [Devlin] put out. It was the first time I felt like there was art being made for me. So that was and continues to be very inspiring. My dream back then was to do a comic for Highwater and I was supposed to do something for

that ill-fated issue of Coober Skeber. About two weeks before Highwater folded Tom e-mailed me to ask if I'd do a comic book pamphlet for Highwater... my dream comes true! But then he folded and my personal life folded -- not because of Tom -- and I spent four or five years putting myself back together and eventually started making a lot more work starting in 2007.

SPURGEON: I'm more familiar with the small-press and 'zine scene from the 1990s than I am the one that exists now. Do things work differently? Does the fact that on-line publication exists now mean that a certain kind of artist works on-line and a certain in print, or does it overlap? Can you sort of describe the landscape for me?

MILES:

MILES: Things are different. It's a different time. I mean, back in 1996 if you lived in the suburbs, you had to work to encounter 'zines and other counter-culture, it took time and bus rides across town and seeking and hunting, it was fun, but now... There's stuff still like that, but the layers of obscurity combined with the perception of digital immediacy have braided and mashed the whole experience to a pulp. Before I started Profanity Hill I was really of the mind that the old centralized counter-culture stuff was better and more fun than the Internet din. Then I got to know

Dylan Williams and had to face the fact that I didn't know nothing and had been selling my experience short by being lazy and stymied by the digital age. If I could explain the 'zine landscape for you, I don't think I'd have started Profanity Hill.

SPURGEON: Can you talk as explicitly as possible about what led you to start a 'zine and minis distributor, what that work entails, how much business you're doing, just generally what that experience has been like so far? Has anything surprised you, positively or negatively? What's the long-term goal in taking on such a project?

MILES: I was tired of hearing myself complain. Seattle used to be a hot bed of 'zine activity and I knew people were still doing stuff but it seemed invisible to me. I could barely find the stuff anywhere. I knew that might be my problem so I decided to start Profanity Hill to see how wrong I was. I mean, you go down to Portland and the town is lousy with 'zines! It's amazing. Everywhere you go there's zines... I actually think there's too many 'zines in Portland. I usually don't pick anything up when I go to one of the Portland shops because there's too many to choose from.

I also started Profanity Hill because I was tired of hearing other people complain about 'zine or comic distribution and Diamond. Profanity Hill started not too long after the Diamond minimum thing. In my opinion, the popular "alternative comix" reaction to that was simply ridiculous. If you don't like something, do something about it. Profanity Hill's been around for almost a year and I do as much business as I want. Whatever I put into Profanity Hill I get back and then some. Does Profanity Hill make enough money to pay the rent? Not on your life. But its a great life. What's surprised me about Profanity Hill is that only two of my orders have been from Seattle... the rest come primarily from California, New York and Texas.

I don't have a long term plan or goal for Profanity Hill other than to stay small and relevant. The only new dimension for 2011 for Profanity Hill is that I'm going to start carrying stuff by out of town 'zinesters and cartoonists.

SPURGEON: A lot of people think of the 'zine and micro-press comics scene as being more community-oriented than comics. Are there differences between the way those two worlds operate? For that matter, is there something about the work you do with Profanity Hill that informs what you do at Fantagraphics or vice-versa?

MILES: That's a good question and one I'm still investigating. I don't know how different 'zines or comics are from each other or anything else. I do know that the most valuable discoveries I've made about either 'zines or comics has come from how the two operate financially. There are things 'zines can do that comics can't and vice-versa. I've heard a lot of people speculate about Fantagraphics and why it doesn't do some of the things that 'zines or small press people or publishers do. More often than not, the reason we don't do t-shirts and silkscreen posters, etc., is because it doesn't make financial sense due in part by the size of our operation. The cartoonists, retailers, publishers, press and readership tend to compare a company like Fantagraphics with other companies that produce material of a similar aesthetic. That makes sense to a certain to degree but when you take into account that Fantagraphics publishes 70 to 80 products each year, compared to

Drawn & Quarterly's [suggested number] and

PictureBox's and

Sparkplug's [another suggested number] and a different picture begins to develop. I'm not saying Fantagraphics is better because they publish more. I'm also not saying 'zinester X is better because they publish less. It's just different.

SPURGEON: Looking very quickly at your bibliography, a potentially ridiculous question popped to mind. What is it that you accomplish through a series, such as Pines, that you can't with the multiple one-shots that you do? For that matter, how much of what you've created do you feel is of a single voice, an overriding creative effort, and how much do you feel you're oriented towards individual projects one at a time?

SPURGEON: Looking very quickly at your bibliography, a potentially ridiculous question popped to mind. What is it that you accomplish through a series, such as Pines, that you can't with the multiple one-shots that you do? For that matter, how much of what you've created do you feel is of a single voice, an overriding creative effort, and how much do you feel you're oriented towards individual projects one at a time?

MILES: In theory,

Pines is a way for me to chart my progress. What's difficult about such an ambition is that I'm constantly trying to get out of my own way. I think if you were to spread out all my stuff and look at it all at the same time... I don't know if you would immediately recognize it was all made by the same person. I'm told that if you read it all then you know it's all by the same person. I dunno... I'm restless and curious about trying different things. Sometimes I wish I weren't. Sometimes it feels like its a misstep because there's this prevailing sense that you need the perceived focus and consistency of

Schulz or

Guston. In reality, I feel closer to

Picasso and

Hockney whether I like it or not. Picasso and Hockney don't let idiosyncratic style quirks define their work; those guys need to try all this different stuff. I feel that way as well. The difference between me and any of those guys I just mentioned is that they're all masters. I'm constantly trying to find my orientation with comics... I always have five projects going at once and its exhausting. I really wish I could just work on a thing, finish that thing and then start the next thing. But what I wish and what I do are strangers to one another.

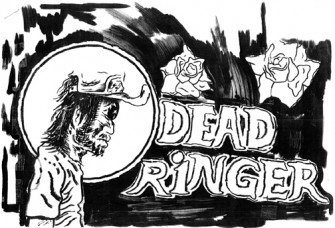

SPURGEON: Your highest-profile project to date is

SPURGEON: Your highest-profile project to date is Dead Ringer

, which you did with Zak Sally's La Mano 21. What was the genesis of that project, and what kind of working relationship have you developed with Sally? What's special or distinctive about working with him as opposed to the other people with whom you work?

MILES: The genesis of

Dead Ringer was an accident I came upon. It was an accident I'd been in, I don't really want to give the genesis away if that's ok.

SPURGEON: That's all up to you.

MILES: I made

Dead Ringer to try and alleviate this thing that was bothering me and I made it without worrying about where it was going to go both in terms of content and in terms of publishing. I made it very large and just did it. It was great to cast off all that comics format baggage... which is something I'm trying to do more of. Just because the Kirby two-by-three grid worked great for Kirby doesn't mean it works great for Billy Graham or Brandon Graham or Austin English or me.

Zak and I basically talked a bunch, and I'd have to say he really edited the thing. The last page had a different line of text and he rightfully questioned what I wrote and I'm glad he did because we I changed it with the help of my Grandmother and its a better book for it. For me, working with Zak was special because I really felt like I was in this hard wake of oblique comic narratives starting with

Justin Green to

Jim Woodring to Zak... so I was feeling this strong spiritual connection even if Zak wasn't. I mean, maybe he was... I should ask him.

SPURGEON: It's been about two years now, how do you feel about Dead Ringer

now? Do you think it succeeds? How self-critical are you generally?

MILES: Yeah, I think it succeeds. It's the best thing I've done. But what I think about it shouldn't matter. I'm self-critical but I don't know how much or how little. How do you measure something like that? Do you compare yourself to other artists, maybe...? I care for my work, I don't hate it. Sometimes I wish I had more control of my work and other times I wish I had no control of it. I've noticed trends about my stuff or my experience making stuff and I've found I have almost zero recall when it comes to the experience of making what I think is my most potent work.

SPURGEON: To take you back into your Fanta-job for a second -- you worked on Weathercraft, with Jim Woodring, a book of the year candidate. Is there anything to working with that material or with Jim in an editorial capacity that provides a different perspective than we might have just picking it up in the store? What is he like to work with?

SPURGEON: To take you back into your Fanta-job for a second -- you worked on Weathercraft, with Jim Woodring, a book of the year candidate. Is there anything to working with that material or with Jim in an editorial capacity that provides a different perspective than we might have just picking it up in the store? What is he like to work with?

MILES: To be clear, I edited

Weathercraft and Other Unusual Tales, which was the Fantagraphics offering for Free Comic Book Day 2010.

SPURGEON My bad. I'm sorry about that. Well, do you have memories of that experience? Was there any carryover between the work you did with him on the comic and what ended up in the book?

MILES: The only editorial input I had on

Weathercraft the graphic novel was batting around ideas for the cover with Jim, Gary, Kim and Eric. What was weird about that was I suggested a cover image off a beaten and battered Man-Hog looking backwards to the left -- very simple and Shakespearean -- and something like the next day Jim e-mails a drawing of something very similar to what I described and Eric and I looked at each other and wondered aloud if Jim was already drawing such an image or if he ran with my suggestion because the drawing, which ended up on the case -- the case is just the hardcover book cover without the dust jacket -- is very elaborate and looked as if it took a long time to execute. For some reason I've never asked Jim about it. So that was cool and mysterious as are many things with Jim.

While working on

Weathercraft and Other Unusual Tales I quickly learned that I simply needed to stay out of Jim's way because he knows what's best for his stuff. So in that case I hesitate to say I "edited" anything because I immediately saw my job as facilitating the production of Jim's vision for the comic. Which isn't to say I didn't make suggestions that ended up in the final comic... it was an amazing opportunity to work with one of my heroes and to discuss how the thing should read and how the thing shouldn't read.

To address your question about a "different perspective" from a reader picking up the book or any of the books we publish, yeah, I have a different perspective and I don't see how I couldn't. I usually read the stuff Fantagraphics publishes as print-outs, photocopies and printer proofs and sometimes I never have the book reading experience with the material. I still haven't read

Humbug as the two-volume set we published. There are times I seriously miss having just the perspective of being someone that picks up a Fantagraphics to read.

SPURGEON: How ambitious are you? If there was a best-case scenario not for next year but for the next five, where would you be in terms of your various creative outlets and job? Would you have settled in on one or two things, maybe? Picked up several more?

MILES: I'm ambitious. I have a lot of ambition... and I've found when I focus too much on my ambition I usually make poor work or my ego gets unhealthy and my work suffers. For the past few years, I've been working towards reducing my ambition. I wish to live without ambition. That sounds pompous, but that's how I feel. For me, the best case scenario five years from now is to still be alive and making stuff. And there's a lot of other stuff I'd like to do besides comics and publishing and distro-ing. I'd love to make a radio play or build some stuff out of wood.

*****

*

Profanity Hill

*

Fantagraphics Books

*****

* photo of Miles provided by the cartoonist

* photo of Miles with Fantagraphics' Eric Reynolds

*

Humbug cover

* cover to a Miles mini-comic

* from Miles' mini-comics series

Pines

*

Dead Ringer

* photo of Miles with Jim Woodring and Kim Deitch

* the Woodring-related FCBD project that was one of Miles' projects

* photo of Miles provided by the cartoonist (below)

*****

*****

*****