Home > CR Interviews

Home > CR Interviews CR Holiday Interview #10—Dylan Horrocks

posted January 10, 2011

CR Holiday Interview #10—Dylan Horrocks

posted January 10, 2011

*****

One of the great pleasures of my professional life is that I get to know people like

Dylan Horrocks. The New Zealand cartoonist created one of the most beloved graphic novels of the modern era,

Hicksville, which was serialized in one of the perfect comic book series of the 1990s,

Pickle, and has given us (at least) three intriguing looks thus far into one of the better ongoing works no matter how slowly released,

Atlas. In 2010, Horrocks has taken to the on-line publication and support of his work in a big way, making not only some of the Internet's brightest and most buoyant comics, but advocating for various issues surrounding art in the digital age in an enthusiastic, eloquent fashion.

We don't 100 percent agree on those issues, so I wanted to ask him few questions about them, to get him on the record in a place where I can access his thoughts on some of those general matters. A fuller bibliography of perhaps more detailed conversations he's had on those matters, a list of links provided by Dylan, follows. I was so inspired by his final entreaty to continue such discussions as a way of potentially reaching a more widespread ethical consensus I actually reinforced my position in one question in the hopes that we get those arguments on-line in their best form -- I did send Dylan an e-mailed apology. I'm glad that if we agree on anything, it's in the hope that change is possible on a cultural basis. More important than any issue discussed, it feels great to have one of my favorite cartoonists so engaged and productive. I could talk to Dylan Horrocks just about every day, and I appreciate his taking so much time before slipping out the door on a holiday trip to speak with me. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: Dylan, I wanted to ask you maybe a half-dozen questions about your advocacy for digital creation of comics, and I thought the best way to start would be to talk about the comics that you put on-line. It seems to me you started, and then stopped, and then started more fully to put comics up through your site. Is that fair? Is this the primary outlet for your serial work from here on out? Is

TOM SPURGEON: Dylan, I wanted to ask you maybe a half-dozen questions about your advocacy for digital creation of comics, and I thought the best way to start would be to talk about the comics that you put on-line. It seems to me you started, and then stopped, and then started more fully to put comics up through your site. Is that fair? Is this the primary outlet for your serial work from here on out? Is Atlas

finished?

DYLAN HORROCKS: Well, truth is I'm like the world's worst web-cartoonist. Everyone says the number one rule for successful webcomics is to post regularly, but...

When I started serializing online, I wasn't really trying to reach much of an audience; it was just a way of putting each page out there as I finished it, so I could get that warm satisfying glow you get from showing something to people. I think I hoped it would force me to work more consistently (I was just coming out of a few years of struggling to finish anything). But for the first while, I was only posting now and then. Sometimes a couple of months would pass and I'd be busy with other things (freelance work, etc). But in May I ran a week-long workshop in Melbourne, Australia for a really inspiring group of cartoonists, and when I came home from that I was all fired up to "just fucking do it" (that was the motto we came up with by the end of the week). So around the middle of the year, that's what I did -- I started posting two pages a week on

The Magic Pen. And I've managed to stick to that since, apart from a gap when

I went to Canada for a book festival in October/November.

I guess I treat the web site as a somewhat looser version of having an ongoing comic -- the way I used

Pickle in the 1990s. So, yeah,

Atlas the comic book is finished (although

Atlas the graphic novel is still a work in progress, albeit shelved for now while I finish

The Magic Pen). The reality is that pamphlet comics are on the way out, especially for "alternative" comics. Most people seem to have either given up doing them entirely, and are just publishing full graphic novels, or else they've turned them into big fat hardcover books (like the latest

ACME Novelty Library and

Palookaville issues). At the same time there's an explosion of comics online -- old hands putting up new work, new cartoonists getting their stuff out there, and a huge range of things that would have really struggled to find an audience ten years ago, but are thriving today.

My primary focus at the moment is finishing a couple of graphic novels, which I'm looking forward to seeing in book form. But serializing online is a great way to keep me motivated while I slowly draw them. It's not for everyone, but it's working really well for me.

SPURGEON: Is there a transformative effect in publishing your work that way? I've always loved your color comics, and I love seeing more of them, and I wondered if making comics that you know will have access to color where that's just probably not going to happen in serial print work is a big deal. Also, it seems if you work is generally looser: I noticed that recently in the Magic Pen serial you've tried different layouts, even a map-like page that was fun to look over. Has the way you do comics, look at comics even, changed?

SPURGEON: Is there a transformative effect in publishing your work that way? I've always loved your color comics, and I love seeing more of them, and I wondered if making comics that you know will have access to color where that's just probably not going to happen in serial print work is a big deal. Also, it seems if you work is generally looser: I noticed that recently in the Magic Pen serial you've tried different layouts, even a map-like page that was fun to look over. Has the way you do comics, look at comics even, changed?

HORROCKS:

HORROCKS: Yes, but I don't think that's due to the web. Well, the color part of it is, because

The Magic Pen was originally being serialized in

Atlas in black & white, but when I started putting it online I gave in to the temptation to do it in color. It seems to suit that story, too (whereas

Atlas seems best in black & white). Besides, it seemed like most of the graphic novels I was reading were in full color, so I figured the economics of it must be changing. A lot of the freelance work I'd been doing was in color, and I felt ready to try using it in my more personal comics.

But the other changes -- the looseness, the playfulness -- I don't think that's from putting it online. I think it's the result of a few things. When I was working on those three issues of

Atlas I was, frankly, pretty depressed. I wasn't enjoying the process of making comics. I mean, it still mattered to me a great deal, but it felt like a struggle, rather than fun. Looking back, I guess that affected the aesthetic choices I was making. With

The Magic Pen, by chapter three -- and especially chapter four -- I was feeling better about life in general, and comics in particular, and I started really enjoying myself. Also, I've been very actively keeping a sketchbook again this year (after a few years where I only drew when I had to), and that's helped me to loosen up and to start thinking about comics visually, more than I ever have before.

That diagram-map page you mention came straight out of me noodling around in the sketchbook (while playing

D&D with old friends!). I was trying to design the setting because I knew I'd soon have to draw that scene, and the more I doodled, the more I started making up details, creatures, plants -- world-building stuff. In the end, I turned that diagram into a page because it was too much fun to resist.

In some ways it's like I've found my way back to where I was in the 1990s, when I was doing

Pickle: drawing comics for pleasure. I don't know if the web-serialisation has anything to do with that, but it certainly hasn't hurt. I love the fact that I post a page and within minutes people are cracking jokes about it on

Facebook or speculating where the story will go next. It's -- well, it's fun!

Having said that, it hasn't worked for

The American Dream, which is the other book I started serializing on the site. Part way in, I started to feel that something wasn't right. And the more I looked at it, the more I felt that the art didn't suit what I was trying to do, and certain bits of dialogue were overdone -- that kind of thing. I reached the point where I stalled -- I was trying to work out how to fix it, and got kind of stuck. Actually, that was when my first period of patchy posting on the site became a long hiatus. Which is why when I resumed posting, I focused on

The Magic Pen, which was just chugging away smoothly without any serious problems.

Since then, I've been experimenting with watercolors, and have started redesigning

The American Dream in a way I'm much happier with. But I don't think I'll serialize that one online. It's the kind of book that needs to be done as a whole, and then tinkered with and refined, and

then put out in public. Of course, I'm keen to still put it online once it's ready (especially as I'd like it reach as wide an audience as possible). But it don't want to actually build it in public, the way I am with

The Magic Pen.

SPURGEON: You've always been someone I think of as in charge of the bulk of work they've done; what creative sensibilities are fulfilled by having this new work exist next to older work, like the late '90s political strips you just unloaded? Are you comfortable with the hosting aspects of having this kind of creative outlet, the implied to very real connection between artist and friends that the immediacy of publishing on-line facilitates?

SPURGEON: You've always been someone I think of as in charge of the bulk of work they've done; what creative sensibilities are fulfilled by having this new work exist next to older work, like the late '90s political strips you just unloaded? Are you comfortable with the hosting aspects of having this kind of creative outlet, the implied to very real connection between artist and friends that the immediacy of publishing on-line facilitates?

HORROCKS

HORROCKS I love the way my web site is completely mine. I can do whatever the hell I want on there -- from occasional blog posts that have nothing to do with comics to uploading sketches and short stories. I grew up involved with small press 'zines like

Razor in New Zealand, which felt more like a scrapbook of comics, drawings, writing, ephemera -- rather than a slick magazine or "product." I feel totally comfortable in that kind of environment; it feels like you're reading these comics in a room full of friends, with conversations going on around you, and the cartoonist sitting right there, waiting to hear what you think of it. That's something I loved about the small press in the 80s and 90s -- that sense of freedom, of a lively unpolished discussion between art and people and back again. So it makes sense that I love the web so much. Blogs, Facebook,

Twitter,

tumblr -- I love it all. And having a blog where I publish my comics, post whatever old stuff seems relevant, plug things I like, vent about politics and get into conversations with people. Sheer pleasure.

So the web site isn't a creative project that I plan the way I do with, say, a book. I mean, it's not a fully-realized, completed object -- it's more like a venue for playing around and engaging with my work and the world in an everyday way. And it's only one part of that; at the same time, I'm also using Facebook and Twitter (and whatever social media fad takes my fancy that month) to explore and discuss ideas and art and music and relationships and -- er -- the hilarious shenanigans my nieces and nephews got up to the day before...

Actually, I was talking about the web with

Seth at

IFOA in Toronto, and he joked that maybe the reason he can't stand social media is the more he learns about people, the less he likes them. I guess I'm kind of the opposite; I just really really like people, warts and all -- which makes the web an endlessly fascinating place to hang out. Including my comics in the middle of all that just seems like a no-brainer.

SPURGEON: Let's stick it to Seth a bit. Can you pick an issue or an idea and talk about how discussing it on the Internet, or how presenting it via art and then hearing back from people through the Internet, changed the way you thought for the better?

SPURGEON: Let's stick it to Seth a bit. Can you pick an issue or an idea and talk about how discussing it on the Internet, or how presenting it via art and then hearing back from people through the Internet, changed the way you thought for the better?

HORROCKS: Oh lord, where to start? Way back when I first started using email (mid-90s?) -- you remember the Comix@ list? I was so excited by the fact I could have ongoing conversations with all these people about comics! As a result, I had far too many, but that process helped shape the arguments I explored in my essay on

Scott McCloud,

Inventing Comics and also fed directly into

Hicksville itself. There were times later when I would say something on

the Comics Journal message board and subsequent discussion would force me to refine, clarify or change my view. More recently (I haven't been on

TCJ for years), there's been Facebook and Twitter, where I've had conversations about everything from politics to comics to the future of copyright -- with friends, cartoonists, writers I've admired from afar -- and my thinking on things has been deepened and enriched.

Even little factual things: when the New Zealand edition of

Hicksville was finally published early in 2010, a NZ literary blogger wondered if it was the first NZ graphic novel. I responded, suggesting a few earlier candidates, and then linked to this on Facebook. Other friends there came up with more ideas, checking dates and so on. The hivemind was at work.

But above all, what I love most about the Internet is the way people share ideas and links and things they're excited by. So, for example, in five minutes of browsing my twitter feed, I get pointed to beautiful new sketches by cartoonists I've never heard of (first time I read work by

Kate Beaton or

Emily Carroll was via twitter), great journalism (twitter led to me to

Mac McLelland's coverage of the Gulf oil spill, and then

Haiti), insightful media commentary (following

Jay Rosen has introduced me to some fascinating things), and -- of course -- plenty of hilarious kittens. Thanks to Facebook, I now know that India is producing a whole new wave of interesting comics -- and because of the way Facebook works, I not only get to see

Amruta Patil's comics (how the hell would I have seen those without the Internet?!), I also get to hear what she's thinking about and listen in on discussions she has with Indian colleagues and peers.

Living in a small town in a tiny country a long way from anywhere else, this stuff is even more valuable for me. I'm enormously jealous of the

Pizza Island gang (for example), who share a studio and hang out with other cartoonists all the time. But via the Internet, I feel a lot less isolated. Sitting in on the enthusiastic playful chatter of young cartoonists helps keep me inspired, and looking at their work has freed up a lot of my ideas about how I proceed with my own. It's a fantastic time to be making comics -- such an explosion of new and diverse voices, so much energy out there -- and the Internet makes it possible to dive in and immerse yourself in what's happening, all over the world and at every level of skill and achievement.

The only drawback is that there's so much out there, it could consume every waking moment. Which is another reason it's been good for me to publish my work online; it gives me an incentive to focus on drawing, not just looking at other people's stuff...

SPURGEON:We recently had a semi-tussle via Twitter about your reaction to Colleen Doran's mid-November posting about on-line piracy and what some argue is its tacit-by-proximity endorsement of the COICA bill. In your summary statement, you seemed to suggest that piracy is a non-issue that is used by corporations and perhaps even governmental interests to facilitate the passing of legal mechanism by which they gain greater control over the Internet. Is that a fair reading?

SPURGEON:We recently had a semi-tussle via Twitter about your reaction to Colleen Doran's mid-November posting about on-line piracy and what some argue is its tacit-by-proximity endorsement of the COICA bill. In your summary statement, you seemed to suggest that piracy is a non-issue that is used by corporations and perhaps even governmental interests to facilitate the passing of legal mechanism by which they gain greater control over the Internet. Is that a fair reading?

HORROCKS: Yeah, I guess so. I've followed the so-called "copy wars" for several years now -- since the days of

Napster -- and ended up reading a lot of books, articles, essays and studies (and, of course, blog posts) on the history of copyright, the idea of "intellectual property" and the never-ending cycle of technological change and subsequent panic in the 'art' industries. It's amazing how often we can have the same hysterical argument about this stuff without apparently learning anything. Exactly the same things being said today about file-sharing and digital copying were said about the VCR, cassette machines, the introduction of television, radio, sound recording, player pianos -- and yet somehow we still have music, we still have movies, people still read books, and artists still make stuff. What's more, the art industries are making more money today than ever before, and continue to earn more every year. Online music "piracy" has been a fact of life now for a decade, and the music business is as strong as ever, even though

The Pirate Bay is still up and running and millions of kids are still downloading music for free. Sure, the structure of the business has changed -- but the biggest change has been the disappearance of CD stores -- but that's not due to piracy; people have simply shifted their spending to

iTunes and

Amazon. So, y'know, I can't help but feel the frenzy of hair-pulling over file-sharing isn't much more meaningful than "home taping is killing music."

The biggest problem, in my opinion, is not so-called "piracy," it's that the "war on piracy" has grown so intense it is having a seriously damaging effect on the culture as a whole. The whole idea of copyright and our understanding of the relationship between artists and their audience and society as a whole has become distorted in a way I feel is increasingly toxic. It's being used to force control over the Internet by government and corporations, to justify increasing surveillance of online activity, to break down net neutrality, to extend copyright terms ad infinitum, to do away with fair use and the public domain, to curtail free speech, to stifle innovation and prevent young web-savvy experimenters from coming up with new business models that could liberate artists from the kind of constraints and dependency we've become accustomed to in dealing with the old art industries.

That, to me, is far more serious than some 13-year old in Alaska or Peru downloading my comics from an unauthorized site. For every 1000 such downloads, maybe one might have bought it if they could? Maybe more -- I don't know. But while we're fretting over all those possibly mythical lost potential sales, our fears are being exploited in a way that's causing much more serious harm.

SPURGEON: Dylan, I want to take a step back, and I hope I can do this in way that doesn't even begin to imply a personal criticism or, if it goes that direction, that you'll forgive me. You've been upfront in some of your interviews -- as well as earlier in this one -- that your thoughts on this general matter were developed via a very personal struggle you had about making art. Do you worry that it's too overly personal for you, that this is a reaction to that extended, bad experience first and foremost? Also, when I hear you talk -- or read your comics -- about your poor corporate comics making experience I never quite understand the core of what made that a bad experience for you? Was it the nature of what was created? The process? A moral objection you have to the result? Everything in equal measure?

SPURGEON: Dylan, I want to take a step back, and I hope I can do this in way that doesn't even begin to imply a personal criticism or, if it goes that direction, that you'll forgive me. You've been upfront in some of your interviews -- as well as earlier in this one -- that your thoughts on this general matter were developed via a very personal struggle you had about making art. Do you worry that it's too overly personal for you, that this is a reaction to that extended, bad experience first and foremost? Also, when I hear you talk -- or read your comics -- about your poor corporate comics making experience I never quite understand the core of what made that a bad experience for you? Was it the nature of what was created? The process? A moral objection you have to the result? Everything in equal measure?

HORROCKS: Well, you're definitely right that my views are shaped by all of that. And they are, after all, nothing more than my own personal thoughts and feelings. I don't think that worries me, as such, because I don't see how it could be any other way. And I try to be frank about the way my personal experiences affect how I feel. There are times when I find myself saying things about the mainstream comics industry that sound uncomfortably like venting and bitterness, and then I start furiously adding caveats and disclaimers.

But then, it's also possible my experiences have helped me explore certain aspects of the industry and of the relationship between art and commerce and so on -- so the fear of not being "fair and balanced" doesn't stop me thinking and talking about it. Especially given that

Hicksville also deals with some of these issues, and I drew that long before I found myself working for

DC. In fact, I often wonder how the person who wrote that story could have made the mistakes I made a few years later. But, y'know, sometimes our fictional selves are wiser than we are.

As for the precise nature of what made it difficult for me, I'm afraid I find it hard to pin down too. To be clear, though, it wasn't the people I was dealing with at DC; I worked with some great people and was generally treated well -- albeit within a corporate structure, so there were constraints and pressures on all of us. It's not like I was having big battles with editors -- if anything, one of the problems was the reverse. I was so keen for it to work out (after all, I really needed the money!) that I tried too hard to second-guess what DC might want from me, and then tried to accommodate that. Which is a terrible way to write, and led to me totally losing my way. I think part of what I did wrong was to go into it without a firm grip on my own vision, and being prepared to fight for it. Even when I did have strong ideas, they would quickly be watered down or weakened -- sometimes through editorial guidance, sometimes through my own misguided attempts to produce what I imagined DC wanted. I don't know. Maybe if I'd just said "Damn it, I want to write these comics the way I wrote

Pickle -- slow and meandering and playful and personal, with very little violence or macho posturing and plenty of sitting around discussing the meaning of life!" -- maybe they'd have been thrilled. Or if I'd written about Batman as the

Donald Rumsfeld of the DC Universe, and his "war on crime" as analogous to the "war on terror," about the need to end drug prohibition, about the way fetishising violence poisons and corrupts lives and societies -- maybe my editors would have said "hooray -- at last he's doing what we hired him for!" [Spurgeon laughs] But because I never had the courage or wherewithal to do that (and because I'd spent so long struggling financially!), I will never know.

So I don't want to act as though it was the DC editors who were at fault; it may have been as simple as me chickening out and failing to write what I should have been writing. Or even more simply: me being so confused and mixed up I didn't even know what to write. But having said all that, I did get to see the inside of the commercial comics production process, and much of what I've said or written about it since is just me trying to get my head around it. So yeah, everything you mention comes into it: the nature of what was created, the process, the morality of the result -- and other things too. The central mystery for me is this: for the first time in my life, I wrote numerous comics about which I felt deeply ambivalent -- emotionally, creatively and morally. How did that happen?

The political and ethical stuff is maybe the most interesting and complex. I remember watching

Bowling for Columbine while writing

Batgirl, and when it got to the scene where

Michael Moore challenges one of the producers of the show

Cops over its fear-mongering and underlying ethnic politics -- well, I really sat up then. The producer came across as liberal and reasonably aware of the issues, and unhappy at the suggestion that his show was contributing to the problems. He seemed to feel the things Moore was criticizing in

Cops were just side effects of the structure of the show. That struck a chord with me because of the ambivalence I felt about the moral tone of the

Batman comics. I felt I was trying to write stories that reflected my values, but actually I never really challenged the ethical and political assumptions built into the very structure of that universe and the conventions of the genre. By the end of it, I began to feel like

Wertham was on to something, when he described the superhero genre as inherently fascist. Might makes right, good vs. evil, physical strength and the mastery of violence as virtues, the city as a decaying jungle, the criminal underclass as a weird inhuman enemy, and so on and so on. Of course, many great writers have challenged and dismantled all of those assumptions; but now I realize what an achievement that was. My stories, in contrast, became increasingly melancholy, tinged with introspective efforts to question what I myself was doing in that horrible world, and occasionally presenting the characters with a wistful vision of an alternative (fictional) reality (which invariably ended up crumbling by the final page).

Anyway, I don't want to pretend I'm anything like a dispassionate observer or critic of what's happening to mainstream comics. For one thing I can't be, and besides, I have little interest in "objective" analysis of art; I'm much more interested in personal responses anyway. I see things going on in mainstream superhero comics these days that resonate with some of the darker trends in American (and Western) culture and politics. That fascinates and disturbs me, but of course I have no idea whether that's a result of my own experience, or if others think so too. It's interesting, though, and enriches my thinking about those broader trends, or at least about the way I see them.

But the business side of it -- the relationship between art and commerce, the corporate structure of the industry and how that relates to personal creativity -- I'm still working through that stuff too. Writing for DC was a fascinating encounter with the vast corporate "culture industry" that spreads from Hollywood to television to comics to publishing and beyond -- and it was fascinating. I came out of it burned -- maybe because of my own weakness going in to it. But man, it was interesting. I'd been so far outside it for so much of my life (immersed in the small press and non-commercial art worlds) it was quite an eye-opener. I think a lot of people within that structure are so used to it they don't realize how weird it is, or how much it shapes what's going on around them and what they're producing. Or maybe it's just me, imagining things. Then again, I'm not the only person to have come out of that industry feeling creatively messed up. I've talked to other people who are still recovering from a stint at DC or Marvel or working in TV or movies. Some people can thrive in that world (

Ed Brubaker, for example, who went into it with a clear vision and stuck to it). But for some people it's toxic. Working out why is part of what I'm doing these days.

That was a very long answer, and might not have clarified anything. But, y'know, it's a work in progress...

SPURGEON: You've talked about making stronger distinctions between commercial and non-commercial copying. What specific measure or what instances do you feel emphasize non-commercial copying to their overall detriment -- I can't think of any that aren't commercial copying focused. Also, isn't the dissolution of arts industries making the distinction between commercial and non-commercial a lot more difficult to make?

SPURGEON: You've talked about making stronger distinctions between commercial and non-commercial copying. What specific measure or what instances do you feel emphasize non-commercial copying to their overall detriment -- I can't think of any that aren't commercial copying focused. Also, isn't the dissolution of arts industries making the distinction between commercial and non-commercial a lot more difficult to make?

HORROCKS: Well, it seems to me the most vigorous efforts against piracy have been directed at file-sharing, which -- let's face it -- is hardly a lucrative commercial industry. It consists of millions of people sharing stuff with each other for free. And even if some torrent tracker sites are earning a heap money from advertising (and I've yet to see evidence for this), the lobby groups and lawyers and legislators aren't restricting their attacks on those, but are actively going after thousands of individual downloaders, harmless amateur web sites and Usenet communities.

The non-commercial -- commercial distinction is important to me because it goes to the heart of why I make art. Sure, I don't want some guy printing up 10,000 copies of my book and making a heap of money off them without permission. Because in that case he's exploiting my work for his own financial benefit. But some guy making a Hicksville t-shirt to give his girlfriend? This makes me happy. A small press cartoonist in Portland drawing a

Lady Night mini-comic? I'm honored and pleased. A fan

uploading scans of Pickle to share with curious strangers? Frankly, I'm touched that he went to all the trouble and delighted that new readers might discover my work. I don't like my comics being exploited. But being appreciated, read, drawn into people's dreams and creative efforts, passed around from enthusiast to potential new fan? All of those things are why I do this in the first place!

The current structure of copyright law makes almost no distinction between all those acts, and in recent years the trend has been to remove what distinctions still remain (by weakening fair use and extending copyright periods so far nothing ever enters the public domain).

Creative Commons licenses do make that distinction -- which is why I use those now whenever I'm able. But the big media lobby groups like the

RIAA,

MPAA, FACT, etc. actively try to undermine Creative Commons and are doing their best to give them complete and permanent control over any copying ever.

And when you look at the way these groups have waged their "war on piracy" over the past 10 years, they've frequently ignored any such distinction, suing (or extorting money from) individuals who are downloading for their own use (students, children, grandmothers), shutting down non-commercial torrent sites, mash-up and remix sites, amateur mp3 blogs and even artists' own web sites. When you felt I was speaking in slogans on twitter, you were probably right. But I feel it's partly because I've been following this issue for several years now, and I've seen the so-called "copyright industry" brandish their simplistic slogans about defending artists' rights while they behave in the most appalling ways. The "war on piracy" is absurd, tragic and extremely destructive, and is waged indiscriminately against fans, amateurs, non-commercial sharers, innocent bystanders indiscriminately. And the collateral damage to net neutrality and online innovation and even freedom of speech means that the stakes are considerably higher than whether some 12 year old kid gets to read my comic for free. It's no coincidence that the very same powers the government is seeking through COICA were recently used to attack

Wikileaks (the seizure of domain names, private companies withdrawing access and services under political pressure). When Amazon kicked Wikileaks off its cloud, its excuse was that Wikileaks was hosting copyrighted materials. There's a reason civil rights activists are worried by legislation like COICA.

As for your last question, are the arts industries dissolving? I don't see any sign of it. I mean, in some cases I'd love to see the existing industry structures dissolve in favor of structures in which artists and their audiences were more in control, but as time goes on, I'm more convinced this was a Utopian (or apocalyptic, depending on your perspective) fantasy and it just ain't happening.

Having said that, the Internet provides opportunities to experiment with new models and structures; and that's another reason the big lobby groups are trying to gain more control over it -- so they can try to influence the paths any new innovation might take. It's just another kind of vertical integration: like publishers buying up printers, distributors and retail chains. So far it's hard to see how successful they'll be; but anything that dilutes net neutrality makes that more likely.

SPURGEON: As you know, I'm wary of talking about these issues in terms of bottom-line costs. Who isn't making money or how much or what. I see it as a creators rights issue: that everyone should be granted the right to set the terms by which people access their material, and that assuming your right to set those terms over a creator expressed wishes is morally indefensible. Do you agree? Why is the discussion mired in bottom lines?

SPURGEON: As you know, I'm wary of talking about these issues in terms of bottom-line costs. Who isn't making money or how much or what. I see it as a creators rights issue: that everyone should be granted the right to set the terms by which people access their material, and that assuming your right to set those terms over a creator expressed wishes is morally indefensible. Do you agree? Why is the discussion mired in bottom lines?

HORROCKS: I agree that the discussion among artists is depressingly focused on money. I mean, I know it's hard to make a living as an artist -- God, do I know it! But is that the most important thing to me? Is that why I choose to make art in the first place? No! It depresses me when you get a bunch of writers or artists or cartoonists together and all they'll talk about is royalty agreements and page rates and who's earning what. What, are we accountants now?

But no artist likes to be exploited, precisely because our work is precious to us in ways more important than money, and we want that relationship we have with our work to be respected. Unfortunately, we live in an economy where money is the most obvious measure of value, and so it's easy to end up focusing on that as the bottom line, as you put it. Often, when you scratch a little deeper, you find that what upsets artists even more is a lack of respect, of being exploited, taken for granted -- even when the work we make is earning someone, somewhere a heap of money and luxury.

But I disagree with your second step. I don't believe I have the right to set the terms by which people access my material, nor where they take it from there. Once I've written a story or drawn a comic -- certainly once I put it out into the world by publishing it (online or on paper), that comic is out there living its own life and interacting with all the people who come across it. It's like having kids. Once you've brought them into the world, they're not actually your property to do with as you will. You have a very important relationship with them, and you deserve to have people respect that relationship. But in the end, they're in the world and they have their own life. Eventually other people will have relationships with them as important as yours -- and it's not fair to try to dictate those terms until the day they die.

If everyone had to ask permission of the author before, say, making a crappy photocopy of a comic to send to a friend, I'd never have seen some of the comics that had the most powerful effect on me as a teenager. Or if an author had the right to prevent me reading their book while eating (in case I spilled food on their favorite page)? Maybe some poets would like to insist on the conditions under which their work could be read aloud ("No you can't read that love poem I wrote for my wife to your fat gay boyfriend!"). If painters could insist on their work only being seen in the original, well, the world would be an immeasurably poorer place.

So I don't agree with your interpretation of creator's rights. And I'd even take it further. I think our rights as creators need to be a lot more limited than they are today. I would like the term of copyright to be pushed back to where it was before the last couple of extensions. Because we also have rights as readers, viewers, audiences, fellow artists who are inspired and provoked by things we read and see and hear. Art is a contribution to the culture, and however important the creator's relationship to that art may be, it's not the only relationship. Ultimately, it might not even be the most important. I've heard from people whose lives were changed by

Hicksville. I mean, really profoundly changed. I almost hesitate to even say that, because it seems arrogant of me to imagine my work could have so powerful an effect. But that's what a few people have told me. Now,

Hicksville is very important to me. I love it dearly. But who am I to say it's more precious to me than it is to those people? If they choose to use it in some way that makes me uncomfortable, do I have the right to stop them?

I don't want anyone dictating the terms under which I can provide people with access to my work. But that doesn't mean I have an absolute right to dictate the terms or conditions under which everyone else can interact with my work from here to eternity. Where there's a conflict, I think the law should err on the side of openness, of work being able to spread through a society and culture. But it's not an absolute either-or proposition. It's a matter of balancing the different relationships that exist around a particular work, and respecting all of those relationships, rather than granting total control to one or another.

SPURGEON: I think you're distorting my position a bit, Dylan. I don't believe the creator has the right to dictate terms absolutely, certainly not to the degree you've suggested. I think they have the right to set the terms initially, and that this term-setting should have some moral impetus. But dictate absolutely? Or even have the expectation that what they've proclaimed will be met to the extent you've suggested? No. I've written several times about copyright limits, for instance, and agree that the cultural good is best served by a much more limited copyright term than what we have right now, which save for the loophole the Superman families are understandably trying to crawl through, tend to serve corporations to the culture's detriment.

SPURGEON: I think you're distorting my position a bit, Dylan. I don't believe the creator has the right to dictate terms absolutely, certainly not to the degree you've suggested. I think they have the right to set the terms initially, and that this term-setting should have some moral impetus. But dictate absolutely? Or even have the expectation that what they've proclaimed will be met to the extent you've suggested? No. I've written several times about copyright limits, for instance, and agree that the cultural good is best served by a much more limited copyright term than what we have right now, which save for the loophole the Superman families are understandably trying to crawl through, tend to serve corporations to the culture's detriment.

That said, within those parameters I'd much rather err on the side of the creator over the individual because I think that also serves the greater good. You and I may not feel that art is best created for commerce, but some art is

created that way, and even more art is created out of some expectation that it eventually leads to remuneration. I don't begrudge anyone the very human desire to profit from what they do. That doesn't mean they get to, but it also doesn't mean they have to be happy ceding any percentage of those aspirations to others' desire to consume. I'm also not certain that employing available means of legal redress automatically puts them in a different ethical/moral category than those who earlier apply available means of technological redress in changing the terms of engagement with that art.

I went to high school about the same time you did, albeit half a world away. We taped shows off of HBO and slipped into concerts at Market Square Arena. These were awesome experiences in some cases, you're right. Yet we never proposed this should be codified into standard practice or ever suggested that the usher or parent who stopped us was violating some right we had, or that Bruce Springsteen was an out-of-touch greedster for having security in the first place. I think there's a huge difference between people breaking with the full extent of a creator's wishes -- it's going to happen! -- and ascribing moral superiority to that position to the point that anyone objecting is mocked, ridiculed and even harassed. Even worse to my mind is then re-applying that framework of logic to primary commercial acts almost solely, it seems to me, because that's of maximum benefit to the person doing the applying.

This brings me to a last question. You seem to believe as a lot of people do that piracy is an intractable cost of doing business, that's it's always going to be there. Aren't we really talking about specific kinds of appropriation from a specific kind of person rather than piracy as a general reality? In the mid-1990s people were quick to cut and paste by-lined prose for their own purposes; people don't do that anymore, despite all the protests at the time that those who objected to this practice had it wrong and should continue to let it happen. You also have individual cases where a request is made to consider an addendum to behavior or even changed behavior and this is a success. Doesn't that suggest that these issues aren't all the way settled yet?

HORROCKS: Well, what you're talking about seems to me to be the gradual emergence of a kind of ethical consensus. And I agree that is far from settled. It's an ongoing process that never really stops. It feels especially volatile and unsettled at the moment because the technology has changed the playing field so dramatically, we're all running around trying to catch up. It's quite possible that in ten years I'll look back on this with a very different view. But it's also quite possible most of those currently upset about file sharing will look back with embarrassment, in the same way we look back on the "home taping is killing music" campaigns of the 1980s.

I also think it's interesting the way an etiquette has emerged around attribution on the web (at least among most serious bloggers). That hasn't been driven by legislation or lawsuits; it really does seem to be the result of ethical opinions being voiced and accepted. I would hope that the same thing can happen in the piracy debate -- that a consensus will gradually emerge over what is acceptable sharing and what constitutes unethical piracy or exploitation. My feeling is that the hysterical "war on piracy" being waged by large lobby groups is not helping at all; like any war, it pushes everyone to the extremes and leaves behind a ravaged landscape.

But it may be that articles like Colleen's and the responses of people like me can help shape a more meaningful consensus among artists -- which in turn might reign in the excesses and steer us toward some kind of decent outcome.

I do worry that the industry lobbyists are so loud and powerful that they drown us all out, whichever side we're on, and I worry that by the time we've reached a reasonable, well-balanced consensus, the law and the Internet will have already been reshaped in ways that suit the big corporate players to the detriment of both authors and readers. If I start to sound a little shrill myself at times, it's because that worry sometimes overwhelms me.

But I hope we can focus on what we, as artists, value the most -- and for me that is reaching out to people whose lives can be enriched in some small way by what I do. That's my bottom line. And that's why, for me, the freedom of the Internet is not a threat, but an extraordinary opportunity.

*****

*

Dylan Horrocks

*

Hicksville Comics

*

The Magic Pen

*****

* photo of Horrocks provided by Horrocks, I think he said taken by his sister

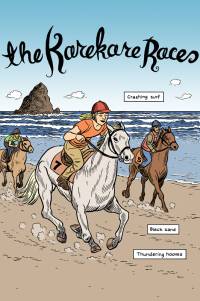

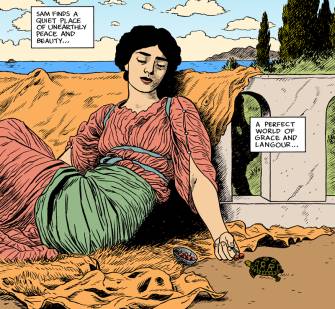

* the lovely colors of

The Magic Pen

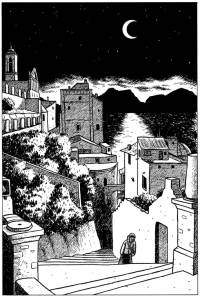

* a stunning page in black and white from

Atlas

* that killer, map-like page from

Magic Pen

* another fun

Magic Pen panel

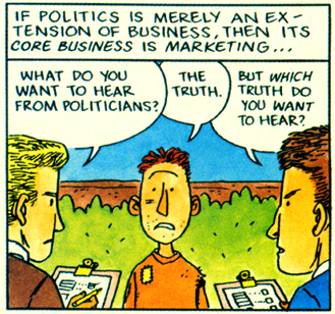

* panel from

American Dream

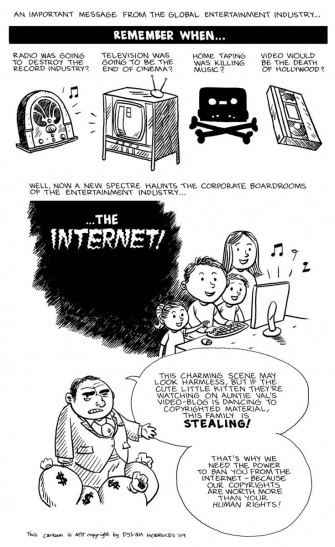

* two examples of random things Horrocks has posted to the site

* a mid-1990s on-line related Horrocks cartoon

* image from

Hicksville

* a well-traveled Horrocks cartoon on on-line piracy

* Lady Night

* two panels or portions of panels ganked from

Hicksville Comics

* a panel from

Atlas that seemed to indicate our partial understanding

* a funny moment in

Magic Pen (below)

*****

Dylan Horrocks On Supplemental Reading"If you want to read other places I've talked about the copyright stuff, Josh Flanagan on iFanboy threw some of it together after our twitter debate.

"In particular, this is an essay I wrote for a NZ magazine called Booknotes (published by the NZ Book Council).

"Here's Techdirt (!) picking up on that essay.

"Here's me talking about it more casually (and probably in a less considered way, due to jetlag) with David Hains when I was in Toronto.

"This is me making a submission to the NZ government on ACTA (and digital media vs copyright in general).

"And here's an earlier submission I made on s92 (an amendment to the copyright act that was eventually overturned after a vigorous public campaign). Note the formatting is ugly as all hell on this post; it was on an old Vox blog, and when Vox closed down, I exported the contents over to Wordpress, but haven't had time to format any of it. One day..."

*****

*****

*****