Home > CR Interviews

Home > CR Interviews CR Sunday Interview: David Boswell

posted June 6, 2011

CR Sunday Interview: David Boswell

posted June 6, 2011

David Boswell

David Boswell created one of the enduring comics characters of the last 50 years (

Reid Fleming) and one of the greatest single comic book issues of the post-underground era (

Heartbreak Comics). Boswell recently came east from Vancouver to Toronto accept the

Giants Of The North Hall Of Fame designation from

the Doug Wright Awards.

I had an opportunity to speak to David Boswell during a spotlight panel held during

TCAF, the comics festival against which the DWAs abut. It was a thrill, particularly given how much the Reid Fleming material meant to me and my friends as teens. A big chunk of Boswell's comics

were collected at the beginning of the year by IDW. Re-reading them I was reminded how little in the way of narrative fussiness there is in what Boswell does, how he avoids the tried-and-true technique of

suggesting a greater reality than might actually exist on the page. I find that brave as far as general creative choices ago, to kind of put it out there, full-blast, beginning to end, nothing held in reserve. It also became clear to me while diving back into his comics that Boswell is one of the funniest set-piece makers and dialogue-honers to ever work in comics. He chooses his words and anecdotes carefully in real life, too.

I am deeply grateful to my friend

Gil Roth for recording the following interview and presenting me with an audio file for transcription, and to Mr. Boswell for his patience and genteel demeanor throughout. As would be the case for a spoken interview not done in public, I tweaked the transcript here and there for clarity. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: One thing I wanted to ask you -- a first thing I wanted to ask you -- is this. Part of your bio is that when you graduated from from school it says you decided to try and become a cartoonist, that you wanted to be paid to do cartoons. I'm not sure that's sensible even now, but in 1974, especially, that sounds to me like an odd thing, a unique thing, to want to do. It wasn't exactly a rich time for comics. Can you talk about how you made that decision? What pushed you into comics?

DAVID BOSWELL: It was not a direct line from college to comics. There were a couple of years in between. Before I became a cartoonist I became a pizza driver. I didn't think of comics initially at all. I was in film school at Sheridan College in Oakville. We all know where that is. At the conclusion of my studies, and I should say I did not graduate. I got an "I" for Incomplete. My film was not done in time. The film was all right, but it was quickly evident that there was no real future in film-making at that time. The only career advice we were given in 1974 was to go to the CBC and apply for a job as an assistant truck driver. Two of my buddies did that, and they were numbers 123 and 124 on the waiting list. And that's how you're going to start? Make a film in 30 years?

So there I was out of film school with a film I tried to get shown on the CBC. A live-action film, not animated. I never thought about drawing as a career until I was forced to. I did a couple of odd jobs for a couple of years after finishing college. One of those jobs was as a pizza driver. You can't disdain that kind of experience, because in a strange way it allowed me to become the chronicler of this guy [references screen image of Reid Fleming], who delivered a different product.

SPURGEON: Part of the story of the creation of Reid Fleming is that he showed up in your sketchbook, and then maybe kept showing up in your sketches. There's a year before when it says you invented him and when he actually saw publication in the weekly comics you were doing at the time.

SPURGEON: Part of the story of the creation of Reid Fleming is that he showed up in your sketchbook, and then maybe kept showing up in your sketches. There's a year before when it says you invented him and when he actually saw publication in the weekly comics you were doing at the time.

BOSWELL: I'll just continue the chronology. [Spurgeon laughs] This job as a pizza driver was not a great job, obviously. But I kept all my tips. And after about six months I had enough to buy a drafting table. A really good, solid drafting table that I still use today. Solid wood, six feet long. My point is that you need to have a good space to work. And preferably a table-top.

The benefit there in terms of what I got, and the experience of going door to door, seeing into people's lives and interacting -- it's obviously what Reid Fleming does. So that led to poverty. [laughs] I had a drafting table. I didn't know what I was going to do with it, but it was a good place to work. I wound up in Toronto here working at a photographer's studio on Church Street. I was the darkroom technician -- not to be confused with gigolo. I made all the prints, and they were really tedious because they were almost all picture of car tires. We had the Canadian tire account back then. Every photograph of a tire had to be made in three prints: a light one, a dark one and a medium one, so that the people that put the catalogs together would have a choice. Working in car tires endlessly, all day long, that became tedious. It wasn't a bad job in the winter, but the real impetus to leave that job and find something else was the change in climate. When the spring started happening in 1977 I couldn't bear being inside the dark all day long.

I'd always kept a sketchbook, but I never thought about comics. It wasn't my first interest. I had a friend who thought I did funny work. Her name was Cynthia. She began to take my work to show her colleagues. She'd report back and say, "Your drawings went over gangbusters, people like what you're doing." I was getting feedback. It made me think that maybe I could do something with comics. The golden moment was hearing that

The New Yorker paid $600 for a single-panel cartoon. My rent was then $45 a week. So I started thinking, a couple of cartoons a year...? [laughter]

What I didn't know was how hard it was to break in. I began to send in packages of single-panel cartoons to publications like

Esquire,

Playboy,

National Lampoon. Before long I had a nice collection of rejection slips. But I was starting to get comments written on the rejection slips by people that were paying attention. I didn't know then but later found out that nobody buys the first time from anybody. They want to see if you can turn out work consistently and repeatedly, that you're not just a one-shot wonder. They'll never buy the first time. What you do is you send them twelve cartoons, they send them back, you send them twelve more right away.

So I was doing that. The cartoons I was sending out then were more enigmatic, maybe, than funny. [laughs] But that wasn't the point. The point was I sent a single page of comics along with the single panels about Lazlo, the great Slavic Lover. It was called "Heartbreak Comics." That got a bit of a response. It wasn't until I was told to send comics to

The Georgia Straight -- that's a Vancouver underground newspaper. It's not underground now, but back then it was still kind of underground. To my surprise, that full-page strip, that was bought by the

Straight. The guy who purchased it misled me as to his actual job responsibilities. He was the advertising manager, not the editor, not the publisher. [Spurgeon laughs] He was also Slavic, so he responded to the character. [laughter] Lazlo's actually Hungarian, not Slavic, but Great Slavic Lover sounds better than Great Hungarian Lover. Anyway, he said, "Send more." And I thought, "Great. I got a weekly gig." The fact that they were paying $20 for a whole page was secondary to the fact that I was getting published. I thought, "Great, I'm a cartoonist now." What do I do next. I have this one page, how do I do another? That's the hard part: how you generate new material.

I had that one comic to my credit, and a weekly gig. I was still living here in Toronto, over on Howland Avenue. Initially I was in a rooming house, which is just like two blocks from here, on Collier Street. Couldn't work there; it was just a room. And a lot of weird people. Strange stuff happened there. I left just as soon as I could. Got a nice place on Howland, with my drafting table. I began to be a cartoonist.

I quit my job in the darkroom. Got my tax return money back, and I gave myself six months to become some kind of cartoonist. That was the Spring of '77. My routine was just sitting in my nice, little sunny balcony with my sketchbook, just doodling. And out of that came Reid Fleming. It was just happenstance. The name was... the bad boy in my kindergarten class was called Reid Fleming. I just stuck that name on this obstreperous character. I think the actual real Reid Fleming has become an Anglican minister [laughter] since those days. He's not the bad little boy anymore. He's never contacted me directly but I've heard that he's out there. Luckily he's not litigiousness and hasn't sued me for using his name. [laughs]

SPURGEON: Some cartoonists regret, when they've had a character as long as you've had Reid, that they've had this character that they came up with when they were very young cartoonists and are now kind of stuck drawing them. Do you enjoy drawing Reid? Is that part of it still fun for you? Do you like the design?

SPURGEON: Some cartoonists regret, when they've had a character as long as you've had Reid, that they've had this character that they came up with when they were very young cartoonists and are now kind of stuck drawing them. Do you enjoy drawing Reid? Is that part of it still fun for you? Do you like the design?

BOSWELL: Well, Reid's tough. He has a very difficult face to draw, with that big, square nose. Some angles it's not hard, but other angles you really have to work hard to get the nose on there without obscuring the mouth and the rest of it. More than that, the personality of Reid Fleming is tough to deal with after a time. I have to get away from him. I'm not like that. He's not my alter-ego. Working on a book for a long time I find I have to leave him behind and do something different. He's not a nice guy. In a way, he's amusing, but you wouldn't want to know a real-life Reid Fleming, perhaps. He'd probably be in jail.

SPURGEON: I think it's remarkable that you've been able to keep him front and center, to focus on a character like that. Certainly in Heartbreak Comics

, the comic book, Reid serves as a supporting character. A second lead. He might almost work better way, or you might be able to not have that negative reaction to him. It seems remarkable that you've been able to use him as a lead. Do you ever regret having this forceful character out there in front?

BOSWELL: Well, he wasn't the first comic I did. The first strip was "Heartbreak Comics," with Lazlo. I'd already done Reid Fleming in my sketchbook. I never thought... well, after a while I did. I thought there was something there. When I first came to Vancouver, I actually tried to do a page of

Reid Fleming, but it didn't work and I knew I wasn't quite good enough to pull off what was inherent to the strip, this certain attitude, and a style. I really wasn't good enough yet to pull it off.

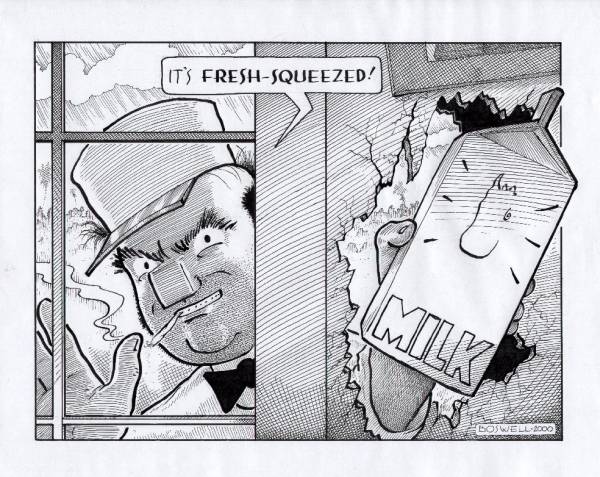

The impetus to try it came out of again, nice weather and my personal life. I was doing this strip about a lover who was working at night. He wore dark clothing. It was a lot of work, a lot of hatching. As the weather became nicer, I didn't want to spend a lot of time, obviously [laughs] on this. Plus I had met the woman that became my wife. Suddenly the theme of unrequited love was a little less relevant to me. Also if I could do the page faster I could spend more time with her. So I had this milkman. Instead of a dark tuxedo he wore white, his truck is white, he worked in the daytime -- it was a lot less drawing. It's basically white with a few lines here and there.

It's not the drawing it's the character that really counts. I did the first page -- that I had in my sketchbook -- over again and better. I put it in there as a one-shot. It was only going to be a one-shot. I thought the whole character was encapsulated in this page and there's nothing more to it. To my surprise, people really responded. They kept saying, "You gotta do more of these." And I kind of said, "There's nothing there to do. It's a one-shot. His whole personality is there on that page." The capper was getting a letter from a bunch of guys that worked in the shipping department at Woodward's. They drew a comic strip showing Reid Fleming bursting into the

Georgia Straight offices -- ha ha -- and taking Lazlo and throwing him out the window and then threatening me [laughter] in cartoon form that if I didn't do more strips with him I'd get in big trouble. I was so charmed by their creative effort I thought, "Well, I'd better do another one and see what happens." And here I am. [laughter]

SPURGEON: You mentioned earlier that Reid is not an alter ego for you. How do you relate to that character? When you're writing Reid, what appeals to you personally about him? Does he simply represent a kind of humor you like? Is he just so out there that you enjoy him on that level?

SPURGEON: You mentioned earlier that Reid is not an alter ego for you. How do you relate to that character? When you're writing Reid, what appeals to you personally about him? Does he simply represent a kind of humor you like? Is he just so out there that you enjoy him on that level?

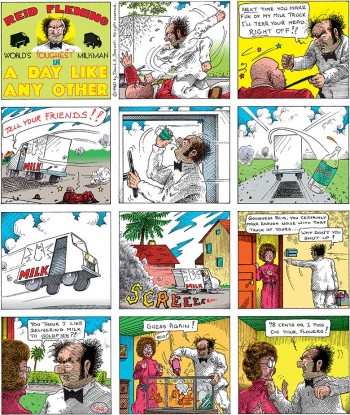

BOSWELL: When I think about it intellectually -- I didn't then, it was just instinctive -- I grew up in the '50s and '60s. The culture to which were exposed then was based on older norms of what was acceptable. That meant the bad guy always got punished. On movies and in TV shows, crime never paid. That first page, Reid Fleming does all these bad things. In the first panel, he's beating a guy up. In the second panel you see it's because the guy made fun of his milk truck. There's an exaggeration of response to a trivial provocation. The whole thing is he does all of these nasty things, and at the end he's threatening an old lady after dumping milk in her aquarium. He's saying, with her up against the wall, "78 cents or I piss on your flowers." [laughter] Which I thought was a good line. It stops there. Before a payoff or retribution, it just stopped. That was the joke to me, that he didn't get punished. He gets away with all of this stuff. The end. [laughter] It's a denial of expectations. It's him doing what he wants to do, and there's no consequence. In real life, of course, there would be a consequence to doing that to anybody, let alone some old lady and her fish. To me, that was the funny part, stopping before the resolution.

SPURGEON: When I told people I was going to be talking to you, a lot of them threw back lines to me like "78 cents or I piss on your flowers." Or "I get my hair cut that way."

BOSWELL: Do

you get

your hair cut that way?

SPURGEON: I do! You have obvious skill with powerful, funny lines. Can you talk about writing lines like that, working them up? Can you remember coming up with the "78 cents" line? Because that's a bizarre but very funny line. Something I think that's funny about it is that it's so specific.

BOSWELL: Well, milk's more expensive now. [laughter] Saying "$1.39" just wouldn't work right. It has to have a certain rhythm. Technically, part of it is the rhythm in both the writing and the visualization. You want to have a flow so people get into that and expectations are created.

I have little mottos in my head that I always make sure I pay attention to when I'm writing. One of them is "thwart expectations." Reid is kind of a predictable character in a way -- you think you know what he's going to do. So you have to make sure you don't get predictable, by changing it, by pulling the carpet from underneath the reader's feet every now and then. So that's paramount, trying to keep it fresh and not repetitive. Some lines repeat well, but you don't want to get so that people are saying, "Oh, I know what he's going to do next."

So the writing part, that's mysterious. Where do ideas come from? If I knew [laughs] I'd make a million bucks. All you can really do is create the conditions for ideas to come. If that means cutting out stress... whatever you want to do to create that space where you can attract ideas. After that, it's just hard work developing it so that it's funny, that it's got rhythm. For me it's very musical. When I write there has to be a pace. When I do a book I make sure the bottom right-hand panel, the last panel, is a strong one so that you want to turn the page, right? I always lay out the stories and panels so that you get to that page-turner, it's a strong panel.

SPURGEON: Very early on, you have a very firm structure in place. Four tiers, three panels. This grid at first. You do eventually break it up, but you don't stray too far from that as your base. That structure exists through most of your comics. That's a lot of beats to have on a page, as opposed to the work of many cartoonists satisfied with a single beat on page or even across two pages. Is that the writing background coming to the fore, do you think? Because your narratives are very involved. Eight pages from you seems like sixteen pages from a cartoonist dealing in those kinds of broader moments told in fewer panels. Do you enjoy having such an engrossing experience per page?

SPURGEON: Very early on, you have a very firm structure in place. Four tiers, three panels. This grid at first. You do eventually break it up, but you don't stray too far from that as your base. That structure exists through most of your comics. That's a lot of beats to have on a page, as opposed to the work of many cartoonists satisfied with a single beat on page or even across two pages. Is that the writing background coming to the fore, do you think? Because your narratives are very involved. Eight pages from you seems like sixteen pages from a cartoonist dealing in those kinds of broader moments told in fewer panels. Do you enjoy having such an engrossing experience per page?

BOSWELL: I think it's important that when you go back to a comic, there's something to discover on a second time, or a third time. So I try to have a subtext. Again, the musical notion would be counterpoint, stuff going on below the main theme. So when you go back to it, there's stuff to discover.

At the beginning, it was a self-imposed limitation, that 12 panels per page. Do you remember

SCTV? A character played by

John Candy,

Johnny LaRue? Does anyone remember that?

SPURGEON: Sure. [various audience nods]

BOSWELL: He had a show called "

Street Beef": man in the street, one camera, one microphone, one interviewer. So with the comic it was the same thing. One pen and twelve same-size panels deliberately as a limitation so that I wouldn't have too much to think about. In a way, limitations force you to be inventive to overcome those limitations. As I got better, I used more pens and different layouts.

Heartbreak I think I used five or six pens and two or three brushes. Triple-zero brushes with white paint and things like that. Initially

Reid Fleming used a single pen for everything: shading, outlining and lettering. That made my job much simpler. Too many choices will just confuse you. Or the readers.

SPURGEON: You mentioned

SPURGEON: You mentioned Heartbreak Comics

. Heartbreak

is a very attractive comic, very lush and lovely looking comic. Certainly it's not like there are no similar elements in Reid during this same period -- there's no drop in accomplishment

with your art. But there's a very specific look. Was it just that you wanted a comic that moved more quickly through the process of it that the Reid stuff is so different? What was it about Heartbreak that you decided to make it such a pretty comic?

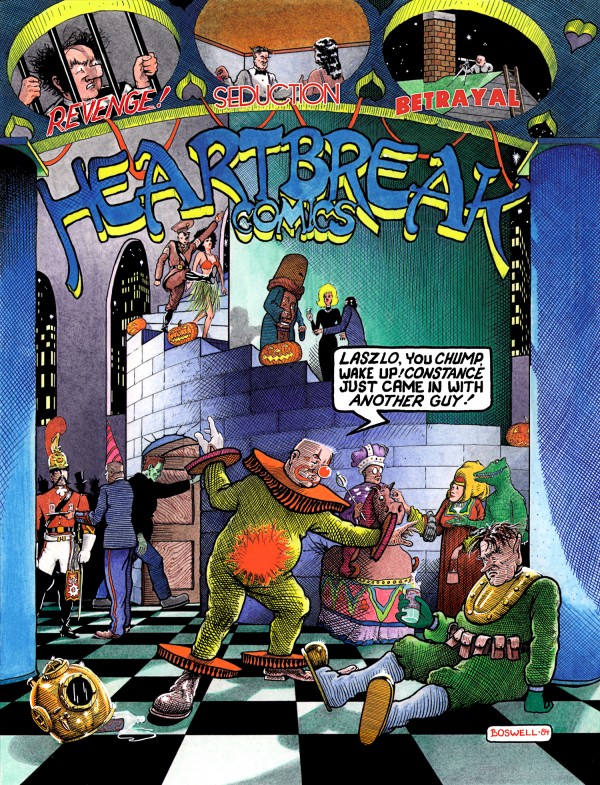

BOSWELL: Pretty? [laughs] The character was inspired by a certain type you see in old movies, '30s movies. The comic European gigolo. That type has pretty much died out in the cinema, but back then it was a comic stereotype. In a way it was thinking about what that kind of guy would do if he was living today. He's trying to impress women by dressing well and being elegant and continental. So to go with that character, the look is supposed to reflect the time in which he existed. It's at variance with the world of today. I wanted it to look like a 1934 Paramount movie, that kind of black and white, and it took some doing to get that good. I wasn't very good when I started. It took a while to get to the point where I could make it look the way I wanted it to.

Reid Fleming looked kind of scratchy. Part of the reason it looked scratchy is because I did the first few pages in my sketchbook, with this pretty rough paper. I would just do the strip, cut it out and hand it in. The scratchiness I thought suited the character. It shouldn't look too refined and elegant. Whereas with

Heartbreak Comics, the smoothness and opulence of the look is sort of what Lazlo would think about himself. He wanted to see himself in that kind of a world. The look should reflect the character's own milieu.

SPURGEON: Similarly, when you did Rogue To Riches, the extended comic-book storyline within Reid Fleming, was there a thought of doing something more ambitious or did that just organically develop? That 135 pages or so of story, very layered and substantive. It works on those terms, although I admit I may not have ever thought about that long story that way until you mentioned it the introductory material of the latest collection. That this was your graphic novel. Did that develop as you went along, or did you decide to do a more ambitious Reid story?

BOSWELL: Well, long story short. I did the first story in 1980, and self-published it. I was fortunate in that

Last Gasp, a distributor in San Francisco, picked it up. I did it in Vancouver and tried to sell it locally. It was doing okay, but obviously... I had 10,000 books. I just picked a number out of the thin air. Which was kind of stupid, 10,000 copies. I was sitting there with all of these books, thinking I gotta sell these somehow. So a friend was going to San Francisco. He dropped in to see Ron Turner, who runs Last Gasp to this day. He looks at the book and says, "I'll take 500 copies." A month later: 2000. I broke even in less than six months and the rest was profit so I thought, "Not bad." That first book's been through six or seven printings now. Never been out of print.

Then in 1986 at a convention in Victoria, B.C., I was approached by

Eclipse Comics. Now defunct. The woman who ran it, or co-ran it,

Cat Yronwode? She told me she had this idea I was some sort of a rich guy who did comics as sort of a sideline [laughter] and otherwise didn't do anything. They offered me a contract to do more, and suddenly I had to fulfill the terms of the contract. So I thought, "What do I do now?"

I had a number of scenes written, in little bits and pieces over the years. I keep pretty extensive notebooks. I never waste anything. The stuff I'm doing in the current Reid Fleming graphic novel I wrote in 1985. Big scenes. I knew that someday I was going to use this. I don't know how, but I'm going to work it in someday, to what I do. So it was basically necessity. How do I do a book? How do I do another book? Keep it going. With that first graphic novel I was making it up as I went along. When I got to that last chapter, I was really stuck. It was like, "How do I finish this? I'm really in a corner." It took a whole lot of thinking [laughs] to get out of that corner, but I used the old plot trope of the surprise father, right? That's been used in a lot of movies and novels. Like

Scaramouche, for instance, uses that plot device. In this case, the president of Milk, Inc. turns out to have been a milkman who generated Reid Fleming with one of his customers years ago. He discovers this at the very end. It all worked. I even had people saying, "I was surprised you were able to finish it, because I though it was going to go off into space." [Spurgeon laughs] But if you read it, I think it's pretty cohesive.

The one I'm doing now, I do know the ending. I know the exact ending. I'm just filling in the blanks to get there. I've got that about 65 to 70 percent done. I've done the first three chapters. It's five chapters. I'm just trying to get the rest of it done for the second volume of <>The Collected Reid Fleming. The first, of course, is out now.

SPURGEON: [to audience] I don't know how many of you have seen it, but IDW did a big, beautiful yellow collected edition of the first half of David's career-making work. What was it like to assemble this material? Did you have negatives? I know that there have been some problems getting negatives for books that were done at Eclipse. Were there any hassles in getting this book put together?

SPURGEON: [to audience] I don't know how many of you have seen it, but IDW did a big, beautiful yellow collected edition of the first half of David's career-making work. What was it like to assemble this material? Did you have negatives? I know that there have been some problems getting negatives for books that were done at Eclipse. Were there any hassles in getting this book put together?

BOSWELL: I had negatives for all of my books, shot by a very professional guy named Bill Cole. He's dead now, but he knew his stuff. He was the best guy. He was recommended by Rand Holmes, another cartoonist. He shot all my negatives, and I made sure I got them back. With Eclipse, they did various printings, and then the business kind of began to go downhill. I found out later they had all the negatives and the original layouts pieces on these big wooden shelves that later collapsed. Instead of picking them up, the workers just walked on them. Cat Yronwode told me this later. Also, this building in which the negatives where housed twice survived near floods. It was on a hill. Water came up and almost engulfed the building.

I got the negatives back with great difficulty when they finally went bankrupt. When I got them back they were scratched, there were footprints on them... some were okay, but I had to do a lot of re-shooting. To answer your real questions, with this book, although I had the negatives they were at the printers from my own printing. I had a bit of a printer's bill I couldn't pay [laughs] so I couldn't use those negatives at all. My dirty little secret is that this book was all done from scans I did myself. Off of good copies.

SPURGEON: The book looks nice enough I never would have guessed that.

BOSWELL: It was scary, because it was like, "If this doesn't work..." But I think I pulled it off.

SPURGEON: What was it like to look at the material again?

BOSWELL: Horrible. [laughs]

SPURGEON: With a lot of cartoonists looking at old work forces them to reconsider it.

BOSWELL: Yeah. I should be a pizza driver again. [laughter]

You're confronted with all of your mistakes, all the things you wish you could do over. When I do a book I never look at it again unless I have to. Because I'm not really a comics guy. Other things are more attractive. So especially with this first book when I was forced to prepare it for publication, I was confronted with the awfulness of the lettering, for instance. In the first book the lettering was something I didn't care about. I just wanted to get it over with. So it's not great, and looking at it again I thought, "Man, this isn't good enough." I spent time on the computer touching up the lettering in that first book, making it more legible. The first thing is clarity. Readers have to be able to follow things without going, "Oh, where do I go next?"

I'm really careful to make things flow. So I worked hard to make that first book more legible. The rest I left alone. I don't believe in going back and redrawing things. Just leave it the way it is. It's a document. For better or worse. The temptation is always, "How can I let that hand pass? I can do way better today." But if you start doing that, you'll never finish. So I let everything stand the way it was and bit my tongue and there it is.

SPURGEON: The newest collection is IDW, one of the newer publishers with at least something of an eye on getting certain properties of theirs made into film. You wrote a very good script for Reid Fleming at one point. The script I read was your script, right?

SPURGEON: The newest collection is IDW, one of the newer publishers with at least something of an eye on getting certain properties of theirs made into film. You wrote a very good script for Reid Fleming at one point. The script I read was your script, right?

BOSWELL: Yeah.

SPURGEON: It was a very good script, but more than that it's one of the few I've ever read that was done by the comics creator. Is that something you're still interested in doing? Was this new reprint project done with that kind of project in mind?

BOSWELL: I deliberately drew the first book to appeal to movie makers. Part of it is having the panels the same size, which is more like a storyboard. You could take it and shoot it pretty much as is. Or a lot of it, anyhow.

The movie... that's a long story. I can give you the short version. The script you read is about 80 percent pure. My two producers, one of whom was Jeph Loeb -- he's a well-known comics writer today for DC. He and his partner had just had a big hit called

Teen Wolf. In the mid-'80s. They initially contacted me when they were still in university in Boston, I think. They were just getting started, and they tried to get an option off me for $150. [laughter] I thought, "Come on." [laughter]

Then I had some experiences with

Dave Thomas from

SCTV. He wanted to play Reid Fleming. It almost happened at MGM after their first film,

Strange Brew. The film didn't do great. I just came across some old notes. Everybody wanted to make the film except the two top guys at MGM. In a way, I'm glad they didn't do it because it's not my script they would have used, and the script that was written I thought really didn't have the character at all.

Years later it wound up at Warner Brothers. For them I did the script that exists today. It's been through countless actors, and would-be producers. Lots of people would like to make it into a film. The studio will not sell it. Period. They don't seem to want to make it, either. [laughs]

SPURGEON: Wasn't there a reading of your script at one point?

SPURGEON: Wasn't there a reading of your script at one point?

BOSWELL: I have a picture of the poster. It was signed. The actor

Jon Lovitz? Anyone know him? He pushed for years. Before him,

Jim Belushi, he pushed very hard to be Reid Fleming. His film career never really took off. Since then, many actors have wanted to play the part. I get letters all the time from different people. I could give you a list, but it's kind of pointless. This project has been stuck there forever.

Movies are not made because studios want to make good movies. They want a vehicle for their talent. The problem is is that there really isn't any actor who I think can embody the part today. There might be somebody out there I don't know. Back then, there was a guy I thought would have been great:

Bob Hoskins. [laughter] If I could have gotten him whenever I was doing the script, '85 or '86, I would have been so happy. He's a guy who can act with his eyes. He has that intensity. Humor, as well. He was considered at the time -- this is 1987 I'm talking about now, when I was working for Warner Brothers, going down there and having meetings and stuff like that. He at the time wouldn't read it unless there was a million bucks on the table. And nobody was offering that.

A lot of other actors were considered. Some are just pie in the sky, I couldn't believe some of the names thrown around. Same thing: it came down to the top two guys at the studio finally reading the script a year after everyone else and saying, "I don't get it."

SPURGEON: Did you see the reading that was eventually done?

BOSWELL: No. That was 1996. He got some of his pals together to portray the other parts.

Lisa Kudrow played Lena.

Ed Asner played Mr. O'Clock. Then for Mr. Crabbe,

Phil Hartman. I thought he was a great actor. I wish he had played Reid Fleming, but no studio would have backed a guy like him. He was a fantastic actor who could play any part. A really utilitarian but accomplished guy with voices as well. They had a real good cast. They did a reading for the executives there. I was not present.

Dan Castellaneta played Cooper; he's the voice of Homer Simpson. Of course Phil Hartman was murdered two years later in his sleep by his wife. Shot him in the head. Twice, just to be sure.

SPURGEON: Is there an ETA on the second book with the new material in it?

SPURGEON: Is there an ETA on the second book with the new material in it?

BOSWELL: My rough gameplan, thanks to IDW, they are trying to get me down to

San Diego next year as a special guest. That means the convention pays all the costs. That would be lovely. That's under consideration right now. So obviously having a second book ready by then would be wonderful. It's just getting it done in that length of time. I gotta say, the last chapter of this book is

huge in terms of what goes on, the events. It's going to be a competition between the dairies, the Milkman Games [laughter], a combination between a Miss American pageant and the Olympic Games. There's a swimsuit competition [laughter] in addition to three-legged races and stuff like that. It entails a big event with many characters. Some new characters as well -- no spoilers! But big sets. I don't have anyone helping me. I do my own backgrounds -- unlike some cartoonists -- so it's pretty time-consuming.

*****

*

Reid Fleming, World's Toughest Milkman, David Boswell, IDW Publishing, hardcover, 224 pages, 1600108024 (ISBN10), 9781600108020 (ISBN13), January 2011, $29.99

*****

* photo of David Boswell at TCAF in early May 2011

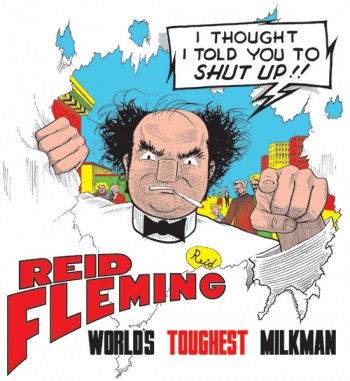

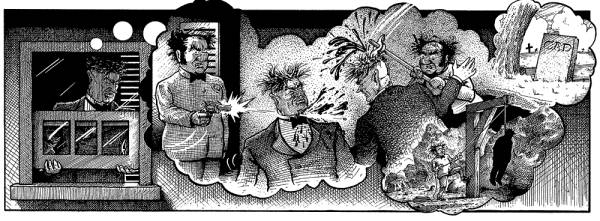

* image of Boswell's most famous creation, Reid Fleming

* Reid Fleming as designed

* first Reid Fleming page, colored

* that solid grid Boswell used on most of his early pages

* cover to

Heartbreak Comics

* cover to the new IDW collection

* a

Heartbreak Comics sequence I like a lot

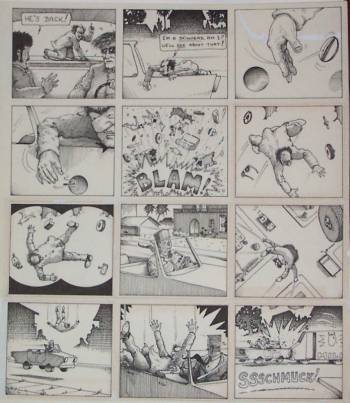

* random Reid sequence I also like

* a pair of single-image Reid things I liked, I think both drawn fairly later on (one below)

*****

*****

*****