Home > CR Interviews

Home > CR Interviews CR Holiday Interview #6—Steve Duin

posted March 22, 2012

CR Holiday Interview #6—Steve Duin

posted March 22, 2012

Steve Duin

Steve Duin is that still-rare creature in the comics world: a full-time, established, working journalist with a sophisticated interest in comics as an art form. He's now a comics-maker as well.

Oil And Water, featuring Duin's writing and with fellow Portland comics community fixture

Shannon Wheeler providing the art, hit stands late this Fall. The handsome Fantagraphics volume details a trip in which Duin participated where a coalition of community members from one part of the country were brought to another part of the country -- in this case, New Orleans and the Gulf Coast after

the Deepwater Horizon oil spill -- in order to bear witness to what they see and assure any locals with whom they come into contact that they're not isolated or alone in terms of the discomfit and discombobulation they're experiencing. I was impressed with its light touch and laid-back rhythms.

I've been wanting to talk to Steve for about three or four years for this series, and I'm grateful for the chance to do so now. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: Steve, two things I know about you is that you have a degree in English and you're right at that age to have experienced the 1980s surge in more sophisticated comics. Are you a comics child of the 1980s? Has your interest in comics ever clashed with your interest in prose, either academic or more generally?

STEVE DUIN:

STEVE DUIN: I only wish I were a child of the '80s [Spurgeon laughs]. The comic book that changed everything for me was parked on the spinner rack in 1968, at Dawson's Pharmacy in

Severna Park, Maryland.

Amazing Spider-Man #68. I was 14, and hadn't read a comic in years, but

Stan Lee's storytelling so engaged me that I spent the rest of that fall sweet-talking friends out of their Marvel back issues at a nickel apiece. The power of the best stories has kept me reading comics and writing for a newspaper all these years, but I don't know that my taste in fiction is all that academic. I wrote my Masters' thesis on

Vladimir Nabokov, but I love

Stephen King and

Alice Hoffman, and I argue, interminably, that

Larry McMurtry's Lonesome Dove is the great novel of the 20th century.

SPURGEON: Since 1/7 of the comics world seems to live there, I think this a fair question. How did you end up in Portland -- or back in Portland, I have no idea -- in terms of your career as a journalist and columnist? Were there other stops along the way? What makes Portland ideally suited for so many comics-makers, do you think?

DUIN: After graduating from

Wake Forest, I spent almost three years writing sports for the

Winston-Salem Journal and picking up that graduate degree in English. I quit the

Journal in 1979, lest I fall in love with NASCAR, and came looking for a new job in the Pacific Northwest. I landed in the small pond that is Portland for the same reason, I suspect, that so many writers and cartoonists do: the mellow pace, liberal politics, desolate beaches and

Powell's Books.

SPURGEON: Am I right in thinking that the first time most of us saw your byline in relation to comics is with Comics: Between The Panels? That's a fascinating book on a lot of levels, full of anecdotal gems, and possessed of the kind of irreverent approach we see all the time now on-line, but also kind of chaotically assembled in some ways. What was that experience like? How were you brought into the project and do you think that book did what it set out to do?

SPURGEON: Am I right in thinking that the first time most of us saw your byline in relation to comics is with Comics: Between The Panels? That's a fascinating book on a lot of levels, full of anecdotal gems, and possessed of the kind of irreverent approach we see all the time now on-line, but also kind of chaotically assembled in some ways. What was that experience like? How were you brought into the project and do you think that book did what it set out to do?

DUIN: In the beginning,

Mike Richardson was convinced we could write an entertaining history of comics if (a) we collected the stories that were told in the hotel bars after

Comic-Con shut down, and (b) we didn't retell them in a linear fashion.

His instincts were right, but that doesn't full explain why the

Comics: Between the Panels came together the way it did. When I write the newspaper column -- which I've done now for 27 years -- I'm invariably looking for a unique voice to carry the essay or rant; if none is available, my voice will suffice. I spent five years researching

CBTP, and I think the book is largely, if haphazardly, shaped by the compelling voices that were available to me, the likes of

Alex Schomburg,

Bob Lubbers,

Bob Fujitani,

George Evans,

Bud Plant and, of course, Mike.

Someone once criticized the book for featuring Hames Ware, a collector/historian from Arkansas, and ignoring

Chris Ware, and the critique is fair. But Hames Ware was willing to talk to me about comics and Chris Ware wasn't.

Jim Shooter was more forthcoming than

Jim Steranko.

Gil Kane was anxious to set the record straight about Stan Lee. There's probably too heavy an emphasis on Golden Age artists in the book, but Mike and I believed someone had to collate their stories before those pilgrims died. And knowing we couldn't include everything in 500 pages, we went with the best stuff that we had.

SPURGEON: For a length of time, and my memory says this was particularly true mid-decade last decade, you were a reliable reviewer of comics. It also seems you're doing less of this now. Interacting with comics is very different for a regular critic than it is for people that only write occasional pieces. Are you still writing about comics? What have you been able to take away in terms of your understanding of the art form and the medium by that kind of writing about it? How were those article received when you started doing them?

DUIN: For several years, I blogged frequently on comics and graphic novels at

The Oregonian's web site. My editors eventually decided, however, that

the blog couldn't support the weight of both comic reviews and political commentary. Fans of the column would arrive looking for rants on former

Gov. Ted Kulongoski and trip headlong over "

Matt Baker Mondays." Comic enthusiasts couldn't figure out why I was carrying on about

Randy Guzek, one of the more manipulative creeps on Oregon's Death Row.

I'm not interacting with comics the way I was 10 years ago; I probably miss that more than the comics criticism. I drag major prejudices to the medium. I am drawn to the kind of storytelling

Nate Powell brought to Swallow Me Whole or

Cyril Pedrosa to Three Shadows. I am ridiculously sentimental when it comes to cartoonists who can fill a panel like

Hal Foster,

Alex Raymond or

Stan Drake. And I want comics to be about something that matters, in the way that

Alison Bechdel's Fun Home matters and

Bryan Lee O'Malley's Scott Pilgrim most assuredly does not. Of late, I'll admit, I've been struck by how few comics are in the

Fun Home category. I'm still reading anything by

Jeff Lemire,

Joe Sacco,

Matt Kindt,

Jason Aaron and my Portland favorites... but, at the moment, not much else.

SPURGEON: This is mostly a not-comics question, but it seems silly to pass up the opportunity to ask these sorts of questions of a longtime working journalist. How were the last few years of precipitous decline and chaos in the newspaper industry perceived by working pros such as yourself and your direct peers? What happened, Steve, do you think? Was it just a loss of a monopoly on certain kinds of advertising and the panic of newspaper no longer hitting their yearly profit margins? Was it really as fundamental a shift as things seem to suggest? Most importantly, is there an aspect to that general story that you think media sources have covered lightly or not at all?

SPURGEON: This is mostly a not-comics question, but it seems silly to pass up the opportunity to ask these sorts of questions of a longtime working journalist. How were the last few years of precipitous decline and chaos in the newspaper industry perceived by working pros such as yourself and your direct peers? What happened, Steve, do you think? Was it just a loss of a monopoly on certain kinds of advertising and the panic of newspaper no longer hitting their yearly profit margins? Was it really as fundamental a shift as things seem to suggest? Most importantly, is there an aspect to that general story that you think media sources have covered lightly or not at all?

DUIN: The last five years have been brutal;

The Oregonian has lost, easily, half of its reporters to layoffs, buyouts... and our embrace of assisted suicide. When you're giving your product away, as we do, why would we expect anyone to buy it?

Earlier this week,

I interviewed Tim Westergren, the founder of

Pandora, the online radio service. Westergren is one of the guys dedicated to redesigning and monetizing a new delivery system for music to an expanding audience. Journalism has been severely wounded by the loss of its major revenue stream -- classified ads -- and the eroding faith that we still believe, like

Gene Kelly in Inherit the Wind, that we are duty-bound to afflict the comfortable and comfort the afflicted. But we also need our own Tim Westergren to rise out of the ashes with a unique delivery system for our best investigative reporting.

SPURGEON: I liked your piece in that early issue of The Escapist. Have you done a lot of fiction writing, a lot of writing that's essentially comedic like that? Were you a fan of the Chabon book?

DUIN: I'm more comfortable with the non-fiction essay than I am with the novel. While I've now sold six books, I haven't found a buyer for either of my two novels. As one of those novels is entitled

Action 1, and deals with the murders of several Portland-area comic collectors, that may not be a bad thing.

I was a huge fan of

Kavalier & Clay, less so

The Escapist. When

Diana Schutz at Dark Horse asked me to do that collecting riff, however, the source material in Chabon's novel was so rich that I had a blast doing it.

SPURGEON: Tell me about

SPURGEON: Tell me about Oil and Water

, why you thought this would work in comics form and, if there's a story to tell, how it ended up at Fantagraphics. It seems noteworthy to me that you'd see this story in comics form, particularly in that I'm not sure you have comics writing credits.

DUIN: In the months following the Deepwater Horizon spill, a guy named Mike Rosen -- who worked for the city's Bureau of Environmental Services -- assembled a group of 22 Oregonians and arranged for them to spend 10 days on the Gulf Coast and "bear witness" -- whatever that means -- to how locals were coping with that man-made environmental disaster. Rosen invited a videographer along to produce a documentary on the trip, and he asked Shannon Wheeler and me to join the troupe because he believed we could somehow collaborate on a graphic novel.

I thought Rosen was nuts. And I made clear that while I was covering the PDX 2 Gulf Coast odyssey for

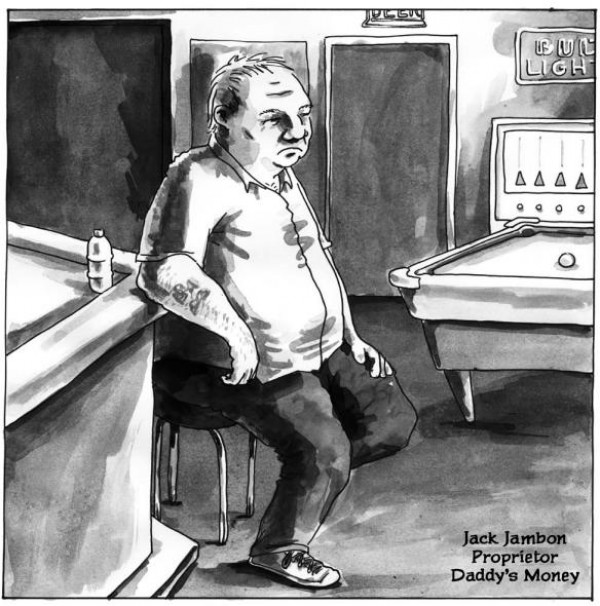

The Oregonian, I wasn't signing on for the graphic novel. Weeks after I returned from the Gulf, I had no vision for how to construct a narrative about the trip... until I wrote the opening vignette on Jack Jambon, the 73-year-old Cajon proprietor of "Daddy's Money," a Grand Isle bar.

"Rewrote," actually, because I'd earlier blogged on Jambon, as indelible a character as you might find in Louisiana. Because tar balls had replaced the tourists on the beach at Grand Isle, his bar was deserted that summer. So, Jambon adapted. He brought in a half-dozen strippers from Slidell, dipped them in Johnson's Baby Oil and set them to wrestling. When I figured out that kicker for that scene -- "You think oil is the problem? You ain't from around here. Oil is the solution" -- the shape of the book began to come together.

Fantagraphics is the only publisher we approached. I'm a fan of

Eric Reynolds, the Fantagraphics catalogue and their design team. I think they took a chance with us, and I'm still thanking them for it.

SPURGEON: Had you known Shannon before working together? He's an interesting Portland-area figure, I think. What do you think of his work generally? What suggested he would be a good partner for this book, considering it's kind of outside his perceived range of interests?

SPURGEON: Had you known Shannon before working together? He's an interesting Portland-area figure, I think. What do you think of his work generally? What suggested he would be a good partner for this book, considering it's kind of outside his perceived range of interests?

DUIN: Shannon is a trip. Before heading to the Gulf, I don't think he and I talked since April 2008, when he invited me to the revival -- or "refill" -- of the

Too Much Coffee Man Opera, and

I panned the sucker. ("Let's put the latest incarnation of

Too Much Coffee Man Opera in terms all Portland coffee lovers will understand: It's Starbucks, not Stumptown. And that ain't good.")

I'm too new to all of this to fully grasp how the perfect union of writer and artist is formed. I was handing a screenplay to a single-panel cartoonist, and there were times when Shannon and I struggled to find common ground. But a great deal of my understanding of what we were dealing with in the Gulf owes to Shannon's perceptions and his sketchbook. He was refreshingly aggressive in dealing with the BP clean-up teams disinclined to give us access. His original poster for the group -- a naked woman starring incredulously at the oil derrick in her bed, and saying "What do you mean, it broke?" -- is brilliant. And it was Shannon who insisted that

Oil and Water needed the half-dozen text pieces that serve as scientific sidebars in the graphic novel.

SPURGEON: One of the intriguing through-lines in

SPURGEON: One of the intriguing through-lines in Oil and Water

is this general criticism of the overall effectiveness of what the Oregon observers are doing in the region. Was that something you encountered, more, or is that something you internalized and wondered about yourself? Is this book an expression of the kind of thing you find valuable about that witnessing experience?

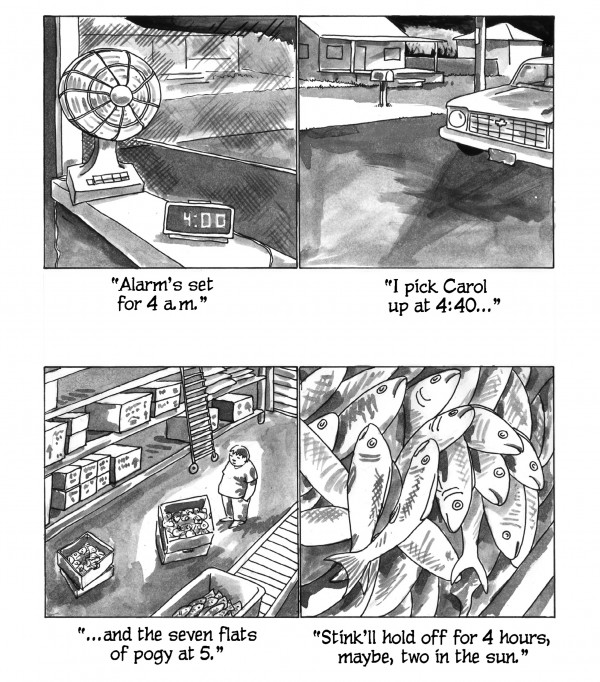

DUIN: We were met with gracious hospitality -- occasionally coupled with wry amusement -- almost everywhere we went. When four of us drove down to Grand Bayou to visit a subsistence fishing village devastated by the spill, our prearranged "tour guides" never showed up. Brian Gainey, however, did. A 20-year-old crabber who works 16 hour days to keep the business going, Gainey took us out onto the bayou for several hours and provided me with a voice to die for.

All of us were wary, however, of the potential arrogance to be found in 22 Oregonians jetting down to the coastal communities of Louisiana and Mississippi and lecturing the hostages of this country's addiction to fossil fuel. We were naive voyeurs. I played that up as much as I did in

Oil and Water for two reasons: I wanted to direct the readers' attention to the locals' more nuanced reaction to the oil spill... and I wanted the book to reflect the doubts that stalk all of us when we try to make a difference.

SPURGEON: Something that intrigues about this work as coming from someone that hasn't done a lot of similar work -- if any -- is how light a touch you have. There are some all-text bridges, but the comics themselves are almost sparsely written, to be honest. Can you talk a bit about the style choices you made, what comics writing you may have looked at in terms of some of the choices you've made?

SPURGEON: Something that intrigues about this work as coming from someone that hasn't done a lot of similar work -- if any -- is how light a touch you have. There are some all-text bridges, but the comics themselves are almost sparsely written, to be honest. Can you talk a bit about the style choices you made, what comics writing you may have looked at in terms of some of the choices you've made?

DUIN: On the first draft of each chapter, I not only wrote the dialogue and voiceovers but also designed the pages, if only to provide Shannon with some comic relief. As I was conscious of the tendency of rookies to overwrite and over-explain, I was forever searching for that fragile point where words ferry the reader to the end of the pier, but the illustrations, the view -- of the sunset, the Gulf or the oil-stained pelicans -- speaks for itself. That approach, however, may owe more to my experience with the newspaper column than my history with comics. Words are much more powerful when they are used sparingly.

SPURGEON: What used to be an island of Joe Sacco and another island of memoir writing you could see from the beach of Sacco Island but was a different body of land entirely has recently become kind of a thriving archipelago. Having just completed a work in this sudden cottage industry, what do you think the strengths of comics as journalistic form might be? And what are the detriments? Was there anything you wished to convey in this book that you then backed away from, or went a different direction based on the form? What do you think the strongest parts of the books might be?

DUIN: I'm much more impressed with the possibilities of comics journalism than I am by the onslaught of comics memoir. Two years ago, I wrote a piece on the limits of autobiography after reading

Drawn to You, by Erika Moen, and

Lucy Knisley's Pretty Little Book. Both cartoonists were willfully boxed in by preoccupation with their own lives. As I wrote at the time, they are young, with plenty of time to experiment and mature, and they may yet "stretch the boundaries of autobiography in ways I can't imagine. But I hope they also come to understand that while the unique details of their own lives is the best place to begin making that vital connection with readers, it isn't necessarily the best -- or only -- place to end."

There are several balancing acts in

Oil and Water, and one of them is between memoir and journalism. I wanted memoir -- the narrative of our trip -- to serve as the vehicle that introduces readers to the victims of the Deepwater Horizon and encourages them to wrestle with issues of social justice. And I believe comics have the power to engage readers on that level because Joe Sacco has taken us to the Gaza Strip; because

Didier Lefevre and Emmauel Guibert found a way, in The Photographer, to use photos and comics to tell the story of

Doctors Without Borders in Afghanistan; and because cartoonists like

Matt Bors and

Sarah Glidden would rather dive into the war zone or the refugee camp than blog from

the local Peet's.

SPURGEON: Were you ever worried about balancing the story of what you were seeing with the story of the people seeing it? You spend ample time with both. Why spend that time with the witnesses in terms of their character issues and narrative arcs as opposed to a more straightforward presentation of the facts as you encountered them?

SPURGEON: Were you ever worried about balancing the story of what you were seeing with the story of the people seeing it? You spend ample time with both. Why spend that time with the witnesses in terms of their character issues and narrative arcs as opposed to a more straightforward presentation of the facts as you encountered them?

DUIN: Of all the balancing acts in the book, Tom, this was the most problematic one for me. No, I didn't go the

Guy Delisle route. For whatever reason -- inexperience? -- I decided the book needed a narrative arc, one in which the alien visitors to this strange planet are changed by their interaction with it. The enduring dilemma of life on the Gulf Coast is that residents are economically dependent upon the very industry that savages the local environment. The most compelling personalities, all of them real, are the 20-year-old crabber; the cocaine-smuggling shrimper; the shark-fishing head of Homeland Security in the parish; and the coastal ecologist who doesn't know how long the mix of oil and dispersants will poison the waters. But I also hoped readers would find, in the interaction of the witnesses, additional reasons to consider their personal stake in all of this.

SPURGEON: I assume that these are real people that you're talking about. Did you get feedback from those people as you did the book? Did they know a book was coming? What's been the reaction thus far from the people most directly involved?

SPURGEON: I assume that these are real people that you're talking about. Did you get feedback from those people as you did the book? Did they know a book was coming? What's been the reaction thus far from the people most directly involved?

DUIN: The characters we met in the Gulf are all real, with the exception of the two black women in "Miracles." The ten Oregonians are, largely, fictionalized composites of the 22 folks who made the trip. Not all of them have seen the book yet. I've had several beers with those who have, and they seem reasonably entertained by what Shannon and I memorialized about the trip and what we abandoned on the beach.

SPURGEON: One of the concluding moments in the book involves someone who just stays there, almost as if they've received a calling to do so. You present that in a pretty matter-of-fact way, but I'm not sure if you felt that was a genuine reaction or just someone bailing out on their life-as-lived as becomes a possibility when you take a trip like that. What did you feel about that person making that decision?

DUIN: In the "Miracles" chapter, there's a sermon board outside the church where we stayed during our first three nights in New Orleans. The board borrows a line from theologian

Frederick Buechner that I've been quoting for years.

In

Wishful Thinking, Buechner writes about the "work a man is called to by God," and suggests that we are called, in the end, "to the place where your deep gladness and the world's deep hunger meet." I think the search for that place is the quest that defines us. It's the

Francis Schaeffer question: "How Should We Then Live?" And we should be wrestling with that question, as Massimo does when he elects to remain behind in

Oil and Water, when we are watching the collapse of the Deepwater Horizon, standing on the beach at Grand Isle, filling our gas tank or turning down that plastic bag.

SPURGEON: What are three memorable comics you read this year not your own?

DUIN: Nate Powell's Any Empire,

Vera Brosgol's Anya's Ghost, and

the ongoing work by Jason Aaron and R.M. Guera on Scalped.

*****

*

Oil And Water, Steve Duin and Shannon Wheeler, Fantagraphics, hardcover, 144 pages, 9781606994924, November 2011, $19.99

*****

* cover to the new book,

Oil And Water

*

Amazing Spider-Man #68

*

Comics: Between The Panels

* I firmly believe this photo to be the greatest bio photo of all time. Not only do I immediately trust that guy, I want to elect him commissioner of the Gotham City police force.

* an arresting image from

Oil And Water

* Duin (far right) and Wheeler (middle) on a panel in support of

Oil And Water

* the running criticism from

Oil And Water

* Duin's light touch

* the drama of the participants in

Oil And Water

* the two fictional characters in a sea of those from real life

* another dramatic image from

Oil And Water (bottom)

*****

*****

*****