Home > CR Interviews

Home > CR Interviews CR Holiday Interview #9—Barry Matthews And Leon Avelino

posted March 22, 2012

CR Holiday Interview #9—Barry Matthews And Leon Avelino

posted March 22, 2012

*****

I met Barry Matthews and Leon Avelino earlier this year when

James Sturm invited me out to his

Center For Cartoon Studies for their annual Career/Industry/Depress-The-Crap-Out-Of-The-Students Day. I was impressed with how forthright and eloquent they were about their publishing enterprise,

Secret Acres -- both their ambitions for it and how while the day-to-day reality of negotiating the boutique press comics business may fall short of any ideals one may bring to the work, it doesn't have to without a fight. Since then I've paid way more attention to that business as a publishing operation as opposed to the place where individual books I always seemed to like were coming out. I've even fallen a bit in love with

their occasional, rambling blog posts, particularly the post-show pieces, the best of which have made me come as close as I get to believing in a comics community.

Secret Acres published

Mike Dawson's

Troop 142 this Fall. Dawson's one of the last remaining straight-ahead narrative humorists in comics, which sets him apart in an age of impressive comics-makers of the decorative, evocative variety. He's also been published by others, which makes him a different beast in some ways than the largely unknowns that have found their way to an ISBN number through Barry and Leon's efforts. I thought this a good time to get into what makes Secret Acres -- a jewel in the present, rich world of small-press enterprises -- go. I was happy they agreed to participate. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: I know almost nothing about your backgrounds -- sadly, this seems to be the major connecting element between this year's interview subjects -- so I was wondering if we could walk through that with each of you. Because of what you do now, can each of you talk a little about your history reading comics, what books or kinds of books were important to you and why in terms of getting you to where you are now?

LEON AVELINO:

TOM SPURGEON: I know almost nothing about your backgrounds -- sadly, this seems to be the major connecting element between this year's interview subjects -- so I was wondering if we could walk through that with each of you. Because of what you do now, can each of you talk a little about your history reading comics, what books or kinds of books were important to you and why in terms of getting you to where you are now?

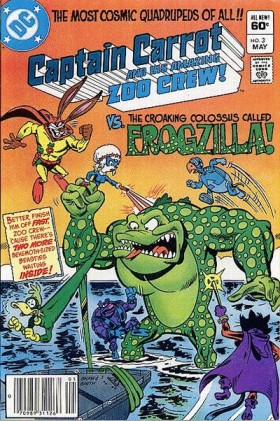

LEON AVELINO: The first comics I read were

Tintin books. In fact, I didn't read them. My mother, a Mexican raised mostly in Paris, had several albums in French and she would read them to me in English. When I later met other kids who had read Tintin, I had no idea who "Snowy" was. She also a had a book of

Pogo comics, and while I liked the drawings, I was clueless as to what the hell Pogo was talking about. When I was eight, my cousin, I believe, introduced me to

Captain Carrot, which got me going to the corner headshop to keep reading them. At some point in third grade, I picked up a copy of

X-Men, mostly because Storm (as I would later find out she was named) happened to be on the cover and was turning into some creature that looked a bit like the alien from the movie

Alien (which remains an obsession, after seeing it six times in theaters when I was six years old). Another kid in the headshop told me to check out Funny Business, which was the local comic shop on the Upper West Side. I was a latchkey kid and I hung out there every day after school until eventually, Roger, the owner, gave me a job. I made three dollars worth of comics for every day I worked shelving and pricing comics after school. I even got to meet

Joey Cavalieri, the editor of

Captain Carrot, who was kind enough to sign my books.

MATTHEWS:

MATTHEWS: I grew up reading

DC Comics as a kid in the '70s. I loved the superhero books along with all of their ridiculous continuity lapses and patches in as time went on. I was a huge

Green Lantern fan. I would hoard comics and I had stacks and stacks of them. When I was around seven, my mother and I lived with her boyfriend in a house that he rented out to students at

Johnson State College in Vermont. Somehow, one of college students got a copy of

Zap Comix into my hands, and it was a mind-blowing experience for me. The idea that comics could be "scary" (overtly sexual, sadistic, irreverent) left a huge impression on me as a kid. To me, it was mildly terrifying that someone could come up with these twisted storylines and then draw them and have them published. I saw that comics had the capacity to be subversive and naughty. The format seemed to be a perfect conduit for the fantasies and fears of the artist, with the illustration allowing for expressionistic impact that words alone could not convey.

AVELINO: Roger and my mother started dating and I made out like a bandit, grabbing a ton of comics that I would later sell to keep myself in ramen during college. I started reading back issues of everything and, later on, comics like

Ronin,

Akira and

Saga Of The Swamp Thing led me to look for more sophisticated comics and books from independent publishers like

Comico and

First. This changed what I thought comics were about (mainly slugfests). They were darker, more thoughtful and artistically way ahead of the Big Two superhero books that brought me to Funny Business in the first place.

I was also drawing space epic comics with my friend,

Jordan Worley, who would later go on to work for

World War 3, but I stopped drawing altogether when he started reading

RAW and became a real artist, revealing my crappy robot drawings for what they were. I stopped working at Funny Business, too, and stopped reading comics regularly through junior high and high school, but in college, a friend of mine who was studying film at USC discovered

Eightball. I picked those up on his recommendation and I started reading

Hate and

Love and Rockets and I became fairly obsessed with

Tony Millionaire's comics as well. Maybe it was the USC connection, but I always thought of those books as West Coast comics.

MATTHEWS: I dabbled in comics in high school, following

Watchmen issue by issue, and reading Alan Moore's

Swamp Thing. I discovered Frank Miller's work (

Ronin,

The Dark Knight,

Batman: Year One,

Elektra: Assassin) and devoured all of it. I loved seeing the super hero material being transformed into well-thought out, socially relevant, intellectually challenging storylines, but I drifted away from comics in college, except for syndicated strips that appeared in the alt-weeklies.

When I first saw

Al Columbia's Pim & Francie, it scared me and thrilled me in a way that

Zap Comix did all those years ago. There is something thoroughly unique to the medium of sequential art, and I have never lost my fascination with the ability of comics to charm or enrage the reader. It is a medium that elicits strong reactions from its readership.

SPURGEON: Am I right in that you both worked in comics at some point? I could be totally spacing on this and it could be just one of you. How was that experience as preparation for what you're doing now?

AVELINO:

SPURGEON: Am I right in that you both worked in comics at some point? I could be totally spacing on this and it could be just one of you. How was that experience as preparation for what you're doing now?

AVELINO: After grad school, between jobs, I went back to Funny Business -- not to work, but because I had somehow gotten it into my head that I needed to reacquire the comics I sold to get though school. The store had moved and was on its last legs, but I volunteered to help Roger build a website. While working on his computer at the store, Joey Cavalieri came in and actually remembered me and my

Captain Carrot obsession. He told me to send my resume to DC, which I did, mostly on a lark and because the nine-year-old me would never have forgiven the adult me for not doing it. A year later, I was hired by

Jack Mahan, who would be a father figure of sorts for the rest of my life, to work in the Editorial Administration department. There, on my first day, I met

Heidi MacDonald, then a

Vertigo editor, who correctly told me that the best writer in comics was

Dylan Horrocks.

Pickle opened up the floodgates. I started reading all the

Drawn & Quarterly books and going through the mini-comic racks at Hanley's with the gang that had quickly adopted me:

Axel Alonso, who had just moved to

Marvel, Vertigo editors

Will Dennis and

Tammy Beatty, artist

Cliff Chiang and

Peggy Burns, DC publicist. This was the first time I ever felt conscious of being part of a comics community.

MATTHEWS: I had never worked in comics or publishing prior to starting Secret Acres with Leon. I worked in business and finance for most of my professional life.

AVELINO:

AVELINO: After Peggy seduced

Tom Devlin,

Highwater Books publisher, at the

San Diego Comic-Con International, she introduced me first to his books and then to Tom himself. Those books, and Tom, would pretty well define my tastes in comics for good. I'd never seen or imagined comics that looked like them. Every book he published was so unique and weird and gorgeous. I remember the first time I read

Skibber Bee Bye and

Non #5 and being overwhelmed by it all, at times forgetting to read and just staring at them. They were everything comics should be. I still read all kinds and genres of comics, but those books will always be home base for me. Like many others, I got sucked into working for Tom, trying like hell to make financial sense out of Highwater, getting tax returns done, paying off debts, and ultimately, incorporating the company. The board consisted of Tom,

Jordan Crane and myself. A few months later, Highwater shut down, Peggy got a job at Drawn & Quarterly and she and Tom split for Montreal. I did learn what to do, and what not to do, from all that, but it was heartbreaking to say the least.

MATTHEWS: I think my practical business experience was a huge boon to us when we were starting out. I felt very confident that I knew how to balance our books, submit taxes, plan and budget, manage AR and collections, etc. I've also worked in the internet for most of my career, so my basic knowledge of web technologies came in handy as well. Leon did a terrific job coming up with the design for our site and stationery -- it's one of the aspects of Secret Acres that we've gotten the most compliments on, and I think that the artists we initially contacted were impressed that we had such a refined "look" to our materials. Leon's concrete comics experience was invaluable and he did all of the legwork in figuring out what we'd need to do to get our print production ups and running. For two people starting out from scratch, our combined interests and talents worked really well together and allowed us to get started very quickly.

SPURGEON: Tell me more about the decision to initially publish and the lead up to your first work. Because your first book was I think 2006, which means it was probably in the planning stages for a little bit, and that would put you back during a time when publishing comics seemed like a crazier decision than it is now.

AVELINO:

SPURGEON: Tell me more about the decision to initially publish and the lead up to your first work. Because your first book was I think 2006, which means it was probably in the planning stages for a little bit, and that would put you back during a time when publishing comics seemed like a crazier decision than it is now.

AVELINO: It was crazy to even consider publishing comics when Barry and I decided, in 2005, to start our company. Crazy is an appropriate word. I'm pretty well educated in psychology, but even I have a hard time identifying what was wrong with me back then. I had grown up poor with parents who once had money, and I'd gone to private schools on scholarships most of my educational life with some of the richest kids on earth. I was always conscious of the fact that I was broke. I got so used to it that when Barry and I started to make a little money, wiped out our debts, had a commitment ceremony and bought an apartment together, I was shocked at how comfortable my life had become. We were talking about adopting then, but it wasn't long before it was crystal clear I was in no way ready for that. I started to lose interest in just about everything. I am worthless, depressed and angry without a plan, if I ever feel uninspired. Barry was quick to see that one of the few things that would temporarily halt my slide into severe depression was the time I was spending with Tom and working on Highwater Books. Randy Chang, another Highwater draftee, had started

Bodega Distribution. Barry put two and two together, and suggested we start a comic company. I believe Barry was trying to save me from myself in starting Secret Acres. It worked.

We sold our apartment to bring down our expenses. We obsessively read many hundreds, maybe thousands, of mini-comics. I even started making mini-comics to trade for more mini-comics. Around this time,

Sean Ford, one of our dearest friends (whom I'd met at DC when he was one of Peggy's interns), had gone off to the Center for Cartoon Studies.

John Brodowski lives in Vermont, so during our visits to Sean at CCS, we made time to meet with John. He was the first person we ever talked to about publishing their work. At CCS, we met

Sam Gaskin,

Joe Lambert and

Gabby Schulz. When we were satisfied that we had read everything there was to read, we made a list of artists to contact. We did a lot of traveling to meet with everyone.

Theo Ellsworth and

Minty Lewis claimed that our stationery was what put us over the top. It was nearly a year before we heard back from

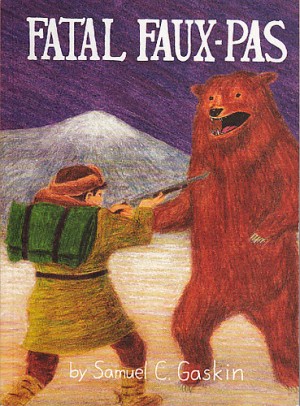

Edie Fake, who hadn't checked his mail for eight months. Ultimately, all but one accepted our offer. We launched the site and the distro in 2007. We published our first books in 2008,

Sam Gaskin's Fatal Faux-Pas and

Eamon Espey's Wormdye.

MATTHEWS: At the same time that Leon was having difficulty arriving at a plan for himself, I was interested in having my own business pursuit. From tagging along with him to MoCCA, I had been exposed to a ton of minicomics and realty exciting small publications.

Jamie Tanner,

Eamon Espey and

Tom Kaczynski all produced work that got me excited about comics again. Leon had experience from working at DC Comics and hanging around with Tom Devlin from Highwater, so I thought that dipping our collective toes in the water of comics publishing would be a natural fit for both of us at the stage of life we had entered.

We created the company "legally" in December 2006 and started contacting artists in early 2007, knowing full well that our first book would not appear until 2008.

SPURGEON: So definitely 2008 is when your first books came out. My bad.

MATTHEWS: There was an extended period of saving every dime we had to fund the first few books. We launched the site and the minicomics Emporium in the fall of 2007. The first two books were debuted at roughly the same time, at

MoCCA 2008, when the festival was still at

the Puck Building in the toasty month of June.

We knew that the margins would be slender and that the first few years would be a tremendous struggle, financially. We also knew that there was a chance that one of the titles might take off, sales-wise. We made tons of mistakes, but were quick to rebound from every last one of them.

SPURGEON: As a follow-up to that more nuts and boltish "this happened and then that happened" question, how did you initially conceive of Secret Acres in terms of mission, maybe, if that's appropriate, but also just in terms of where you saw a place for yourselves in the overall constellation of publishers working that same general terrain? Did you see people not being published? Did you see a kind of book you wanted out there. Did you think in those terms at all?

MATTHEWS: In my recollection, we really wanted to have a small group of artists we could champion, publish and support. For everyone that we've published, it was inconceivable to us that they didn't already have homes for their work, and I don't mean for that to sound like hyperbole. The books that we publish seem essential to us, the epitome of what comic art can accomplish. Whatever we've published, the books always struck us as absolutely necessary.

AVELINO:

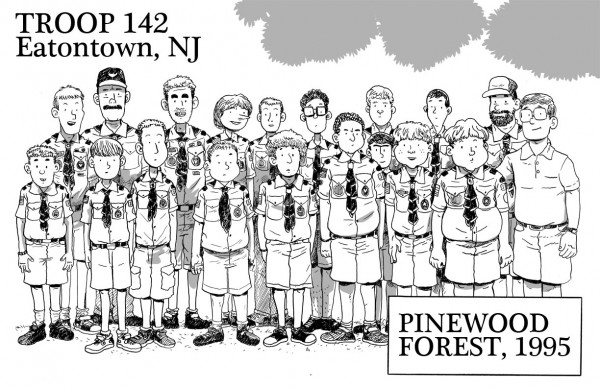

AVELINO: Our fantasy was to find a dozen unpublished artists and publish everything they did and that would be Secret Acres. Mike Dawson, who had books out from

Bloomsbury and

AdHouse before coming to us, forced us to break that rule for good, because the alternative of skipping his book was not a real option. We tried, and continue to try, to avoid having a mission statement. A big worry for me was that we would turn into something people could pin down. I think we've been pretty successful in that regard. It would be a difficult thing for someone to put together a Secret Acres book. Our tastes are fairly broad, but I'd be surprised if anyone managed to cater to them. This is where I part company with Tom, who had a manifesto and a real agenda with Highwater. It was easy to get the sense that he was looking to fix comics and that he knew exactly what it would take. We are nowhere near that specific.

We do, however, need to be able to identify an artist at first glance. The comics we were drawn to were distinct. They couldn't possibly be confused with the work of anyone else. They also had heart, no matter how disturbing or abstract they might be. The proof of this was in meeting the artists. They are some of the best people I will ever meet. I'm honored to call them friends. Funnily enough, before we went diving headfirst through every self-published comic we could find, the one artist Barry and I both agreed we'd love to publish was Jamie Tanner. I'm sure his name was mentioned the night Barry first suggested starting a company. Jamie was the lone artist to turn us down, having found a home at AdHouse Books. We were right about Jamie, too, he's a great a person, as is the AdHouse captain, Chris Pitzer.

MATTHEWS: I think we hoped to always work with the same group of artists instead of being a stepping stone for people to go on to work with more established publishers, but the reality is that we will have some artists that outgrow us and go on to do larger-scale projects. I still expect that we will be able to grow to meet the needs of artists that stick with us. It makes me extraordinarily happy that everyone still wants to do books with us and we're beginning to do our second (or third) books with the artists.

In terms of content, I think Leon and I are proud of the fact that the work we publish is varied. We don't subscribe to any kind of aesthetic guidelines that dictate whom we work with. We expect the comics to be distinct and identifiable and compelling.

AVELINO: Our place among other publishers was determined by other publishers. Randy Chang has been always been our friend, was at times a mentor and makes a great confessor. We might have gone mad were it not for the fact that we could bitch and moan to Randy. Through Randy, we met

Dylan Williams, whose love of our books and constant encouragement were critical for us. Both Randy and Dylan let us pile on to their events. They sent us to

Tony Shenton, our sales agent. They helped us find printers. A lot of what I do as part of Secret Acres is new to me, and I have to have blind faith that somehow I'll figure out what it is that I'm doing along the way. Without those guys to lean on at the start, I don't think Barry and I would have made it this far. Over the years, other people have found us. Chris Pitzer has been a great big brother to us. Being around

Annie Koyama is like finding out Santa Claus is real. Much like the way we fell in love with the artists behind the comics that we wanted to publish, so it has been with comics publishers. The people who publish the books we adore are just what you'd expect them to be. Our place among publishers is with our friends. We're happy to keep earning our spot among Bodega, Sparkplug, AdHouse and Koyama Press. We're a good fit. I hope.

SPURGEON: Are you the same publisher you were five years ago? How are you different? Do you see the company differently, even?

AVELINO:

SPURGEON: Are you the same publisher you were five years ago? How are you different? Do you see the company differently, even?

AVELINO: Five years ago, Barry and I were on the road to splitting up, I felt like the man who had everything and was losing it, and we were both of us still following our convictions that Secret Acres was a good idea. I must really love regrets to have so many, but years of therapy later, I feel pretty good about myself and my life. It would have been nice if it hadn't cost me so much, though. Secret Acres has kind of been our kid, Barry's and mine. It's the last thing I would give up. I'm a better human being now, due in no small part to taking care of Secret Acres. When we started, I was focused on making something out of nothing and in a near constant state of quiet panic over what I couldn't do. Now, I'm focused on the the fact that there's nothing I wouldn't do for Secret Acres. It has not been smooth sailing. We've had to cancel books. We've printed too many of certain titles. We screwed up our pricing. These are mistakes we won't make again.

MATTHEWS: Since we were in our infancy five years ago, I think it's impossible to be that same publisher. That said, we are infinitely wiser about the business than we were five years ago! Print costs, print run sizes, cover pricing, sales: we have learned so much over the past five years. When it gets into the business specifics of publishing comics, we are savvier and a little more conservative than we were five years ago. But we're also more innovative and willing to roll up our shirtsleeves to get projects into the hands of readers.

AVELINO:

AVELINO: We were profoundly affected by

Dylan Williams' death. We were at the

Small Press Expo when we heard. After a very difficult year in 2010, which saw the company nearly grind to a halt, we'd been having our best year by far through 2011. We were debuting

Troop 142, which was off to a great start.

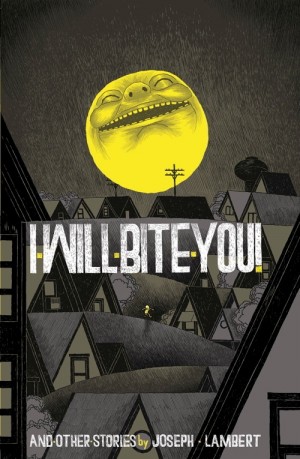

Gaylord Phoenix and

I Will Bite You! were about to win three

Ignatz Awards. When tragedy is sandwiched between triumphs like those, it's impossible not to stop and consider what it all means.

For me, it was clear that Dylan was right about most things. There are a lot of us, these comic-loving weirdos and cartoonists that Dylan lived for, and our numbers are growing. Dylan was fearlessly devoted to doing only what he loved and he insisted that should be our goal, too. I'm still a little divided on that thought. I worry that if I quit my day job, or even if I allow that to be my goal, I'm going to start making decisions with Secret Acres in terms of how it will pay my bills and not in terms of making books out of what these supremely talented cartoonists are producing. They're taking an astonishing risk, handing their art over to us. After SPX, I was determined to find ways to honor that commitment.

Caroline Small wrote about this year's SPX as an education in comics as a spiritual pursuit. She's right. Comics is as much of a religion as it is a medium, maybe more so.

MATTHEWS: Content-wise, I believe we are the same publisher. We are still committed to all of the artists we started out with and we still believe that their work should be published and lauded. We might be working with a couple of more established artists, but we feel the same about their comics as we do the comics of some of the more fledgling artists we work with. We still carry a large number of minicomics that we believe represent the the very best self-published books available now.

I am a much more confident person than I was five years ago, as a person and as a publisher. Starting out, it was easy to second-guess decisions we were making, but nowadays there are fewer unknown variables for the business. We know how to market books, manage print run timing, troubleshoot production issues, discuss editorial input with artists. The stress of looking out for the business and trying to ensure its longevity is plenty reduced, and a lot of that comes from a renewed sense of self-confidence on my end.

AVELINO:

AVELINO: As a publisher, I'm no longer thinking of what Secret Acres is or is going to be. The artists we publish will determine that for me. I'm trying first and foremost to protect the company, so that we don't have those stretches like the middle of 2010, where we wind up wondering if we're done for. I believe we have finally crossed some line where we will never again have to entertain those thoughts. We're learning how to print our own books, like our latest,

Curio Cabinet #5. We're learning how better to control print runs, without sacrificing quality. We're looking at what works for other publishers, we're trying to figure our way into digital publishing and we're working on restructuring the way we handle whatever money we do make so that our artists can take home more of it.

I'm reluctantly coming around to wanting to do this as my job and not just as my religion, but it's more important to me that the people we publish have that opportunity, too. They may make things that only a very lucky few will appreciate, but I'll be damned if they're going to miss out on being able to make things all the time because we're eating whatever profits there might be. From the start, we've always put the cartoonists and their art ahead of every other concern. We have to make good on the promise that, no matter what, the artists we publish will always have a home for their art with Secret Acres, even if they outgrow us. It's always seemed strange to me that other publishers passed on the people we publish, whether the books were hits or not. If publishing something beautiful that is defiantly uncommercial is crazy, then we're still crazy. In a lot ways, Secret Acres hasn't changed at all.

MATTHEWS: To be honest, I see Secret Acres as a little scrappier and more DIY than I anticipated it being when we started out, and I consider that a very good thing, because it shows me that Leon and I have created a publishing entity that can evolve and mature. It seems as though the print publishing world is changing daily. The growing pains of satisfying a digital readership are beginning already, even for small publishers. Secret Acres is lucky in that it has a small, flexible infrastructure that allows us to adapt to industry changes far easier and more quickly than larger publishers are able to. Our decision to bring some of our smaller printing projects in-house is an example of this. We're finding that we need to be as self-reliant and resourceful as many of the artists that we work with. We're developing along with the indie comics market, and I am actually pleased that some of the decisions that we make can surprise me and don't match the expectations I had five years ago. In my imagination, I think I thought that we would be slicker and glossier than we ended up, but five years into Secret Acres, I couldn't be happier with where we've arrived -- in many ways, it seems perfect to me.

SPURGEON: Talk to me about satisfying those digital customers. Are you talking about digital comics, or just those people that find you on-line? What's your digital footprint now and where do you want to be in, say, three years? Are you worried at all about finding your way in what seems like a completely different way of publishing?

AVELINO: We are talking about digital comics, though there really aren't many digital customers to satisfy. We've yet to make the leap into digital publishing. We've flirted with other publishers about developing digital comics together, but those conversations have so far gotten us nowhere. We keep a close eye on the digital comics marketplace. There are several players jockeying for market share leadership, all of whom seem to be following the

iTunes model, which works well for

Apple and sucks for just about everybody else.

Digital comics don't sell very well. The numbers (and, yes, we've seen actual numbers from publishers great and small) are minuscule. Even among record-breaking titles, sales of print comics average out to something above one hundred fifty times that of their digital counterparts. This may change, and rapidly, considering that the two major eReaders,

Kindle and

Nook (and really, Kindle), are now comics capable, but I'd be shocked if the folks looking to be the comics version of iTunes are currently operating at a profit, no matter how big a cut they take, and they take a huge cut. Again, behavior might change now that comics aren't trapped on the iPad, a device that only a small percentage use for reading. Maybe the

Kindle Fire will save comics, but that seems unlikely, too.

The readership seems thoroughly confused by all this. Digital comics being priced identically to their print edition seems to piss a lot of people off, but they don't seem to understand what costs go in to making a comic and it's difficult to grasp that a digital anything might have a price tag of any kind. In much the same way that a self-identified liberal progressive will shop at Whole Foods, an extremely conservative company that hates them, because organic and heirloom just sound progressive, the same is true of the free internet. Free sounds egalitarian. Free killed the terrible music industry. Free also means monetarily worthless and it has pretty well killed the financial prospects of every kind of creative professional, musician, writer, artist, journalist, filmmaker, publisher and, of course, cartoonist. Personally, I'd rather see webcomics as strips in alt weeklies so their creators don't have to rely on the generosity of an audience that doesn't think they should pay for what other people make (and yet they have no problem with ISPs and tech giants taking their money hand over fist). It's contagious, too, as even publishers and the few remaining alt-weeklies expect to get their comics in exchange for probably worthless exposure.

We're not crazy enough to think digital comics and eBooks are going to save us from anything. The truth is the current dominating digital publishing technology, ePub, makes comics look like absolute dogshit. We will never put a comic on a phone because you can't really read a comic on a phone any better than you can watch a movie on one. If you can't comfortably see a whole page, you're not getting a whole comic. Just imagine reading Jack Cole's

Plastic Man or Theo Ellsworth's

Capacity on an iPhone, or better yet, don't.

We are interested in developing the highest quality digital comics possible and it appears technology may be catching up to us. It's worth doing if it expands the readership of the books we publish, but we're not kidding ourselves. Secret Acres' digital footprint, even if it's growing, is tiny. The finished work is the printed book. The same is true even for the cape crowd and their monthly chapbooks. Digital comics never made anyone fat. Comics aren't text. Form matters in this medium more than it does in any other. I used to say that the technology that's killing the creative professional is what made Secret Acres possible, but now I realize what a crock that line was. It did make for a nice sound byte, though.

MATTHEWS: As Leon indicates, the digital sphere is not going to have an impact on our sales, but there's no doubt in my mind that future comics readers will be reading comics on devices in dominant numbers. Watching various companies and publishers jockey for market leadership in the digital book realm is exhausting, but I think the market will establish itself eventually. We're hesitant at this point in time to just go with one of the established digital players.

We do want to offer our books digitally, but we haven't come across a format that really works or that capitalizes on how beautiful comics can be. To read a book on

comiXology using "

Guided View" is to experience the worst of what digital comics reading can be: the images are zoomed and oftentimes blurry, the panels are cut into odd pieces that seem disconnected from the narrative, and each other. It is clearly an aberration, but at the same time, it isn't very comfortable to read a comic book on a Kindle Fire. I've begun reading submissions we get on the iPad as pdf's, and it's the closest I've come to feeling comfortable reading a comic digitally. However we experience comics in the future, I think it will either be a larger ereader than a Kindle or Nook, or the format itself will morph into something that is easier to consume on a small ereader.

I believe that the digital format presents a fantastic opportunity for creators to introduce their work at a low price point to an interested audience. I am surprised that the big digital players have not tried to create some kind of self-publishing gateway for creators. It's a missed opportunity. There are so many talented artists that most people don't get to read unless they attend conventions or are able to mailorder minicomics. A digital minicomics marketplace could really help a lot of artists get their work seen and enjoyed.

At this point, I think whatever Secret Acres does digitally, it's going to be a very controlled, self-reliant experiment. If the new ePub specs truly make comics more digitally friendly, we will probably jump in, but we have yet to have a single customer ask us if any of our books is available digitally, so I don't think that there's a rush, but we plan on getting involved in the near future.

SPURGEON: When we did the CCS career day this year, both of you spoke forcefully about the failure of Diamond to provide basic service in terms of what your company requires. What is your relationship with the DM right now, with that company and with comics shops? Is it mostly through Tony? How big a component is it of your business, to have work available through these shops. For that matter, how many shops carry your work, period?

MATTHEWS: Retail sales are the bulk of our business, and orders that come through Tony tend to be the majority of those. One of the reasons that

Baker & Taylor and

Amazon are valuable is that they don't need to accept or reject books. They simply make the books available to customers. All of our books belong in comics shops, even if Diamond deems them to be too low-volume to suit them. There are a large number of shops that ordinarily order through Diamond that have begun to order whatever they can through Baker & Taylor so they can return items that don't sell. Leon and I are perfectly fine with this because we never get returns, and Baker & Taylor offers even small publishers more competitive rates than Diamond. This is an arrangement that works better for everyone (the small publisher, the retailer, the distributor) except Diamond. As near as we can tell, Diamond has turned its back on any kind of long-tail business practice and is wholly engaged in being a life support system for Marvel, DC and a handful of larger publishers. No matter how much we love the mainstream comic book, we believe that the majority of inspiration and potential for growth in the medium lies with the independent comics industry.

AVELINO:

AVELINO: At this point, I'm not sure whether the problem is with Diamond or us. [Spurgeon laughs] I don't think we've ever shipped a Diamond order without some kind of catastrophe of lost books or books that were never marked as received or some other kind of administrative nightmare. Diamond is wildly inconsistent when it comes to our books.

Wormdye, one of the top 25 books of the last decade per

The Comics Journal, was rejected because Eamon's writing wasn't up to professional standards. Then it was accepted. They flatly turned down

PS Comics, classified the Eisner-nominated

Monsters as porn and listed it in their adult catalog, while books like

Lost Girls and

Paying for It were totally okay. They rejected the winner of the Ignatz Award for Outstanding Graphic Novel,

Gaylord Phoenix, then ordered large numbers of

I Will Bite You! and small numbers of

Troop 142, which they then followed up with a huge re-order. I have no idea how seriously they take us. Diamond is like a box of chocolates.

Though it would be nice if we had any idea what to expect from Diamond, at the very least, we don't depend on them all that much. The porn orders for

Monsters, for example, only represent about seven percent of that book's total sales. Most of our presence in the Direct Market is a result of Tony Shenton's efforts to shoehorn us in there. Our books are carried by 60 or so comic shops and independent bookstores via Tony, and who knows how many via Diamond and Baker & Taylor. Not every one of these stores carries all of our books, of course, but we do depend on them to stay in business. We also depend on them as comics fans, too. As big as Amazon is for us as publishers, and it's a huge sales channel, we do go out of our way to support independent bookstores and comic shops. Along with conventions and libraries, they're the core of the comics community, and the reading community and maybe the community, period. Their importance to me, personally and professionally, can't be overstated.

SPURGEON: You mentioned Troop 142

, this last Fall's release. That is a different project for you guys for reasons other than that Mike had previous publishers. Did he bring specific experiences to the table that you felt helpful? Did the fact that it was serialized on-line and through mini-comics help the book at all? What's been different about shepherding this book through?

AVELINO: Troop 142 started strangely in terms of how Barry and I got to it, which was individually, not as Secret Acres. I'd been reading it online, and had recommended it to Barry several times, though he rarely listens to what I have to say. Barry read the mini-comics that Mike sent as submissions for our web store. Though we'd both read

Freddie & Me, Barry never made the connection to that book. He was excited enough about the minis to want to publish

Troop 142, but when I pointed out to him that this was

Freddie & Me Mike Dawson, we both abandoned that thought. We're not poachers, and it appeared Mike already had a publisher, so we were happy to carry the minis and leave it at that.

We only met Mike at last year's SPX. Barry actually did most of the talking, but Mike got the message that we loved

Troop 142 and had given that story a lot of thought. About a month after we got back home, the three of us went out to dinner to discuss publishing

Troop 142. This still seems weird to me, in all honesty. Not because of the content, since our books are all over the place in line with our tastes, but because it was the first time we'd picked up anyone with a publishing history. Everyone else we'd published was still figuring things out when we'd met them. We really had no idea what we were doing back then, either, so it was also the first time we'd picked up a book as a somewhat-fledged company. The whole thing felt very adult to me.

Everything moved a little faster with Mike, like we'd all gotten a head start on publishing

Troop 142. The editorial process was a breeze. Nobody really had to explain where they were coming from. It's difficult to say whether or not the book being serialized online or in mini-comics has had any impact on how it works as graphic novel. I do get a little frustrated that some people think they're getting the same story online as they would in the book, which is way better. That's not my opinion, it's a fact. I was also a little nervous that Mike would be disappointed by us, because we're a much smaller company than he'd ever worked with before. I must have forgotten about that somewhere along the line, because he feels like family to me now. The family thing is a very big deal to me. We don't publish books so much as we publish artists, so it's important that these folks enjoy being a part of whatever Secret Acres is, because they are going to be a part of it. Really, they don't have much choice.

MATTHEWS:

MATTHEWS: Several pages into

Troop 142, I knew that I wanted Secret Acres to publish it. We get a lot of fine submissions that make us excited to give the artists more exposure, but

Troop 142 was truly thrilling and surprising. Since it was a submission to the Emporium, I did not think that Mike was looking for us to consider it for publication, particularly since he had worked with larger publishers. When we all met and discussed the project, it was so flattering to discover that an established artist was interested in working with us.

As Leon mentioned, I think the serializing ended up being misleading since the final book had tweaks and enhancements that made it substantially different than what Mike had originally posted. People felt that they had read the book, when really they had only read parts of the book. The edits that Mike made were thoughtful and significant to how the story reads. In years of editing comics and fiction, I don't think I've ever seen someone respond so positively and productively to editorial suggestions. When he submitted the final book, it was thrilling to read all over again, and I couldn't be happier that Mike trusted us enough to let us give him comments.

SPURGEON: You talked about SPX, and I saw you at Brooklyn's show... how many shows do you do a year? Are they important to your bottom line? Important in other ways? Is the current convention/festival set-up close to what you need from shows like that, or could you use certain changes?

AVELINO: We do somewhere between eight and ten shows a year. These conventions, art fests and fairs are huge for our bottom line. I'm not sure if it's a coincidence or not, but this year it seemed as if sales at shows and through our site were riding a seesaw together. We saw a huge increase in convention sales over the year go hand in hand with a steady decline in online sales. I suspect attendees are going to cons with a shopping list in hand. It's a bit annoying to me because we're so devoted to carrying and distributing self-published comics and mini-comics and, unlike our books which move through stores, we can only sell them at shows and on the site. We carry some great comics by some very talented people and I'm not sure that many folks think of Secret Acres as a place to get those minis, and they should. Two artists we love who are not, at this point, part of Secret Acres, took the time to e-mail us after SPX and tell us that we were officially their favorite publisher, because we still rep minis so hard (their phrasing). I like watching folks discover stuff at the Secret Acres table, especially when it's one of the artists we publish finding a mini they'd never heard of before.

The shows are where we get the encouragement that we need to keep this ball rolling. When your heroes come by to pat you on the back for a job well done, it's tough to be bummed out by the mistakes you make and the grind of building a comics publishing house. Like cartoonists, the majority of what we do is done alone. This is probably what leads lionized cartoonists to become frothing Libertarian lunatics. Outside of shows and signings and other odd events, the only time I've ever gotten to see Secret Acres in action is when I notice some beautiful person reading one of our books on the subway. We need that direct contact. I suppose we could hang around in comic shops and wait to see someone buying a book, but that's a little too stalker for my liking. The shows are also the only way we get to hang out, all of us, together, which is priceless for me.

Really it all goes back to what Dylan was talking about, how, at this point, indie comics can grow along with the increasing number of freaks who love this stuff. His argument was that we don't have to reach across the manga or superhero or Hollywood aisle to thrive. We can all keep making and publishing the stuff we believe in. More and more of the right readers will find us. You can actually watch this expansion happen, standing behind a table at SPX or BCGF or

TCAF. It's not a fad, like the coming and going of major publishing houses through the world of literary comics. It's a constant.

MATTHEWS: I have nothing to add to Leon's response!

SPURGEON: [laughs] I'm taken by the statement made earlier about the tremendous amount of trust involved for an artist to turn their work over to you? We have so many publishers that exist for so many reasons, that I wonder how much that is part of the ethos anymore. What ideally are you able to do for someone that you publish? What do you think you'll be able to do better as Secret Acres grows and flourishes?

AVELINO:

SPURGEON: [laughs] I'm taken by the statement made earlier about the tremendous amount of trust involved for an artist to turn their work over to you? We have so many publishers that exist for so many reasons, that I wonder how much that is part of the ethos anymore. What ideally are you able to do for someone that you publish? What do you think you'll be able to do better as Secret Acres grows and flourishes?

AVELINO: Sometimes it seems to me that publishing, of any kind, is under attack. We are the evil gatekeepers, depriving the world of great and unusual work with our focus on profits. Looking at the behavior of some publishers out there, we may deserve the bashing we get. I'm a little sick of arguing about Kickstarter, but I will say that it should be completely unacceptable for a publisher, meaning a publisher with an office and interns, to find funding through charity. Yet there they are. A certain comics publisher once said, aloud, during an interview, that they wouldn't publish creators who weren't good at promoting themselves. I thought this was vile, but the interviewer never even came back to that. The fact that that comment wasn't met with a spit take was both demoralizing and energizing, in the sense that I felt compelled to offer Secret Acres as a counterpoint.

One thing technology has done well is open the doors for self-publishers. There are plenty of cartoonists out there who don't need us or any publisher, and that would include some of the people we publish. I've supported more than a few Kickstarter projects, personally and through Secret Acres, but it's as much a popularity contest as it is a resource. I also despise the idea of comics as charity. The work of a cartoonist has value, even if it only provides a living wage for a handful of creators. If, as a cartoonist, you can do this on your own, without the support of a publisher, by all means go ahead. However, I don't think expert self-promotion should be a requisite for being a successful cartoonist. That drives me nuts. Making comics is tough enough without that pressure.

MATTHEWS: I'd like to think that we provide a real and necessary service for the artists that we publish. Producing, printing, marketing and distributing books is time-consuming. Not as time-consuming as

making those books, of course, but that's kind of the point. When someone gives us their book, we're taking all of the other responsibilities on our shoulders: negotiating with the printer, storing the book, sending out review copies and press releases, nagging journalists, submitting materials to distributors, filling orders, invoicing and collecting, etc. We know for a fact that our contracts are close to the most artist-friendly agreements in the industry. We only want to work with people we like, and we're pretty confident that the feeling is mutual.

As Secret Acres grows and flourishes, all of the artists we publish will grow and flourish right beside us. I think we do a great job garnering reviews and attention, and I think we're able to handle our sales adeptly. Continuing to be able to publish everyone that we want to is still the end goal for me. I'd also like to see us get more books into more hands -- I believe unquestionably that everything we publish

needs to be read and enjoyed by as many people as possible, and that is always what I want to help accomplish.

AVELINO: Before we really got off the ground, Tom Devlin, interviewed on this site, said that we were starting a company with every great mini-comics artist you'd never heard of, and that we'd succeed where others had failed in making money off of publishing and distributing mini-comics. We're not all the way there yet, but we're close. More to the point, these mini-comics artists aren't exactly unknown anymore. I wouldn't say they're rich and famous, either, but they've garnered awards and honors and an increasing audience for their work and they've done it by working together and with us. They participate in Secret Acres in ways they simply could not at bigger houses.

The artists we publish work in a medium that is the toughest and slowest going and, more often than not, not very financially rewarding. We can promise them a home for their work, our unwavering admiration and respect, the best convention snacks in the industry and maybe some decent pocket money. Secret Acres isn't perfect, but I submit our catalog as evidence that we can do some great things. It might not be obvious that there's a connection between

Gaylord Phoenix and

Troop 142, but that synergy is real. The more they produce, the more we publish, the better we all do. I think we're getting to the point where people trust to put out good comics, even if they don't look alike. Though I don't think we're in this to make stars, maybe in the future the oddball stuff we do won't be such a hard sell.

SPURGEON: Did you make the right choice?

AVELINO: Yup.

MATTHEWS: It seems impossible to me now that it ever felt like there was a choice to be made.

*****

*

Secret Acres

*****

* photo of Barry

* photo of Leon

* an issue of

Captain Carrot

* an issue of

Zap

* action from

Ronin

* from

Pim & Francie

* Highwater's inspirational

Skibber Bee Bye

*

Wormdye and

Fatal Faux-Pas, the first two books

* Mike Dawson

* from

Gaylord Phoenix

* cover image to

I Will Bite You!

*

Curio Cabinet #5

* from Theo Ellsworth's

Capacity

* from

Monsters

* from

Troop 142

* Sam Gaskin's

2012

* from the very professional-looking web design material (below)

*****

*****

*****