Home > CR Interviews

Home > CR Interviews CR Holiday Interview #13—Colleen Coover

posted March 22, 2012

CR Holiday Interview #13—Colleen Coover

posted March 22, 2012

*****

For me, one of the happy surprises of the Fall was the

Colleen Coover-drawn

Gingerbread Girl, a collaborative work with her husband the writer

Paul Tobin. It's presently out in collected form from Top Shelf after a reasonably high-profile run as a serialized, on-line comic. I knew going in that

Gingerbread Girl would be professionally done and well-crafted given the creators involved, but I wasn't quite ready for how ambitious, slippery and endearingly odd the resulting work -- about a girl who believes she has a twin that's been lost to her, told through the perspective of multiple witnesses -- ended up being. The artwork by Coover puts on fine display her hard-won years of self-study of a range of cartoonists, and builds on the experience of work that she's done in a variety of previous professional gigs. This includes an Eros title (

Small Favors), an all-ages title (

Banana Sunday) and some extremely well-liked work at

Marvel Comics, of all places -- a significant number of those short stories were written by her

Periscope Studio mate

Jeff Parker, who created with her distinct style in mind. I've been wanting to talk to Coover for a few years now, and even if I hadn't liked the new book as much as I did I would have been grateful for the opportunity

Gingerbread Girl provided for the two of us to speak. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: Am I reaching you at Periscope? I talked to Jeff Parker as part of this year's series, and we spoke about how nice it was to work in a space like that one, amongst other cartoonists. Do you feel that way as well?

COLLEEN COOVER: Yeah, totally. When I first started coming in here, it was a part-time thing. I had moved here about a year earlier, and they invited me to come around. It was a really hot summer, and there was air conditioning here! [Spurgeon laughs]

That was when I was still working on

Banana Sunday, and I had never really been around other pros for any length of time, other than conventions and stuff, and other than Paul -- but he's a writer, not an artist. He and I would analyze other people's art. But it was like this grad school program [laughs] all of the sudden, where I had all this hands-on advice from other pros. And that just keeps on happening organically throughout the studio. We have interns from SCAD or MCAD or whatever come through, and we learn a lot from teaching them.

SPURGEON: Not only hadn't you been in a collective studio before, but if I recall correctly, you were largely self-taught. You hadn't had a lot of formal art training, period, so being around other artists in general

might be a new experience for you.

COOVER: I had been an art major for one semester at the

University Of Iowa, but this was like in the late '80s, where representative art was anathema. [laughs] People were doing some bullshit abstract thing and talking about the process. Illustration: oh my God! Comics: what?

SPURGEON: You've talked about this a couple of times: you and Paul Tobin moved to Portland from Iowa. You've put out there some of the things you wanted out of the Portland community making that move. Can I ask you

SPURGEON: You've talked about this a couple of times: you and Paul Tobin moved to Portland from Iowa. You've put out there some of the things you wanted out of the Portland community making that move. Can I ask you why

those things were important to you? Because there are a lot of cartoonists that enjoy the relative isolation of living in places like Iowa City, being part of a community that's not necessarily an artistic one, or simply standing out as the local cartoonist. What was important to you about getting into a bigger cartoonists' community, aside from just enjoying being around like-minded folks?

COOVER: It was partly wanting to get our careers going. The best way to network is to be around other people doing what you do. And that worked out. We had other professional friends in Iowa, but none of them actually lived in Iowa City.

Phil Hester lived 40 miles away, and he was the closest guy. We would see him at conventions. [laughter] He and Paul are old friends; they worked together in the '90s when they were both starting out. That was pretty much the extent of our Midwest network, other than at a Chicago show or something. So that was a factor.

Mostly it was a personal thing. My sister had moved to New York City, and we visited her. That was the first time either of us had been to New York. We looked around ourselves, and we're like, "We've both been living in Iowa for over 30 years, and if we don't move out, we're going to be there for the rest of our lives." As pleasant at it was to live in Iowa City, and as

easy as it was to live in Iowa City -- it's a very easy place to live, it's a university town -- we weren't involved with the university, we weren't going to be involved with the university, and we weren't going to raise a family there because we don't want kids. We needed something new.

I wanted something urban and livable. Portland is totally that. I think that's one of the reasons that there are so many cartoonists here, because it's so livable. Having

Dark Horse and

Oni and

Top Shelf here is icing on the cake.

SPURGEON: Is there any downside to living in a community like that? I know that generally it's a very artist-friendly community. Is there any time you feel too indulged in your artist proclivities?

COOVER: No. [laughs] The thing about me, is when I meet people who don't make comics, I don't know what the hell to talk to them about. "What do you mean you don't?" [laughter]

I can't think of any downside. One of the continuing upsides of the community is that there's none of this weird snobbishness that has existed in the comics industry for whatever reason -- between superheroes and independents and blah blah blah. We're all buddies, right? We've got

Ron Randall here, who's been making superhero comics since the '70s, and we have

Steve Lieber, who's done both. And we've got [Jeff] Parker, who's done both. And then we've got

Erika Moen, who's entirely webcomics. We go to parties and stuff together. We all like each other, and we like each others' work. I'm trying to make it not sound too utopian, but it kind of is.

SPURGEON: I want to ask you a bunch of questions about

SPURGEON: I want to ask you a bunch of questions about Gingerbread Girl

. I thought that was an intriguing book. There wasn't a ton of press out there about it back from closer to its release, but one thing I read is that even though you and Paul have worked together for years, you still worked from a full script on this.

COOVER: Yeah.

SPURGEON: Is that how the two of you just prefer to work? And does that mean you don't have any input until after you get past the script stage?

COOVER: Paul's not really a writer who likes interaction; he's not a springboard kind of a guy. He's more of a "get on a train track and ride until he gets to the end" guy. When it came to me, then, I didn't go through and say, "Hmmm... maybe

this will be better." There's always little dialogue tweaks that you do, a sort of self-editing. But that's really the extent of the storytelling collaboration.

SPURGEON: I read in the same piece that you will read a script multiple times before you start to work on it. What is that process like? What are you looking for when you first dive into a script? Is it just to get a feel for it?

SPURGEON: I read in the same piece that you will read a script multiple times before you start to work on it. What is that process like? What are you looking for when you first dive into a script? Is it just to get a feel for it?

COOVER: Yeah, it's to visualize what's going on and then break it down to storytelling elements. Paul is a very descriptive writer. He'll set up the scene pretty definitively in his scripts. I'm working on a story with Parker again right now that's way more fluid. "And this is probably happening..." [laughter] I sort of have to take it from there. Parker and I do a lot more of the back and forth, because he writes in a much looser, let-the-artist-make-her-own-way sort of style. He sits at a desk right behind me, and I can just say, "You mean like this?" And he'll go, "Well, no, more like this." And because he's an artist he can show me rather than just tell me.

It depends on the writer. When I'm working with a writer I don't know, or is in New York rather than over here, I tend to take the script that I get and follow it as closely as I possibly can. Find a way to tell the story my own way. I recently

worked with some TV writers, some guys from

The Daily Show:

Wyatt Cenac and

Elliott Kalan. They were writing these humor gags. I wouldn't even think of suggesting changes as far as the overall script. Sometimes I'll say, "Hey... maybe this dialogue can go this way, maybe?"

I try to sublimate my work more to writers I don't know as well. Because that's going to be a situation where I'm working for them work for hire. They were hired to do their job; I was hired to do my job. I feel like it's a more commercial relationship. Which is fine, because I kind of enjoy that. I enjoy that sort of restriction, because then I have to earn my way through it. When it's with someone I'm friends with, like Parker or Paul or

Fred Van Lente, I can play around a little bit. I can say, "Hey, look at this clever thing that I did." And they can say, "Yes, it is very clever. Thank you, Colleen. You're very clever." [laughter]

SPURGEON: Now the basic shape of the page in

SPURGEON: Now the basic shape of the page in Gingerbread Girl

, was that something Paul contributed? It's not a standard comic-book page; it's more squat. I think there's a four-panel grid in terms of the basic storytelling structure, too, although you hardly keep to that. What was the idea behind working at this size and with that structure?

COOVER: I remember it was a definite choice we wanted the art to be square. I drew it eight by eight. But I don't really remember why. It seemed more... graphic novelly?

SPURGEON: [laughs] Was it that you knew it would be serialized on-line?

COOVER: No. That was a suggestion of

Brett Warnock's. After about two seconds of us going, "Ahhh! Giving it away for free." We went, "Oh, yeah, that

is a good idea." It's such a non-genre kind of story. It's very difficult to describe. I still have real difficulty when people say, "So, what's it about?" I'm like, "It's about this thing and there's this girl and she might be crazy and maybe not and there's all these people..." I just ramble on and it sounds awful.

SPURGEON: Well, there is

an aspect to Gingerbread Girl

that resists easy explanation. Even exposed to it on-line, I got to a certain number of pages assuming it was going to be one kind of story, but then it turned out to be very, very different than that assumption. So it's certainly something that explains itself over several pages as opposed to a few, let alone a lending itself to a tag line.

COOVER: I feel like it was important to let potential readers make up their own mind about what it was before they went ahead and bought it. It's not a thing you can just tell people, you know.

SPURGEON: You also have superhero and all-ages readerships; both you and Paul do. I imagine it could be very alarming if you were a great fan of those genres to come to this work cold.

COOVER: I'm under no illusion that it's a story for everybody. It's kind of a mind-bender. I was so happy when I saw

A Serious Man by the Coen Brothers. "Okay! It's like this!" [laughter] There are no answers. That's what it's all about. It's not about definitive answers. It's about the mystery. It's not about finding out what's what.

SPURGEON: I thought the coloring was very attractive: a single-color used throughout the book in terms of a shading technique as well as providing texture. Was that your contribution?

SPURGEON: I thought the coloring was very attractive: a single-color used throughout the book in terms of a shading technique as well as providing texture. Was that your contribution?

COOVER: We knew that we wanted it to be a single-color book, looking at

Ghost World and books like that. I picked the color because it seems kind of cinnamon-y, kind of ginger-y, which would be appropriate. It seemed like it would provide the right mood. And of course we have this rainbow cover that

Tim Leong designed so brilliantly, and it makes for a nice juxtaposition.

SPURGEON: Had you worked with a single color before?

COOVER: I had worked with graytones before, and to me it's basically the same thing. It's just picking the right hue. I thought a little bit about blue, but it made it a bit too

Fun Home-y, or too much like

the Parker books. I wanted to give it its own color and identity.

SPURGEON: How picky are you about color? Because your work holds color very well.

SPURGEON: How picky are you about color? Because your work holds color very well.

COOVER: Oh God, I'm so picky about color, Tom. Have you seen me

rant about purple on-line before? Because man, I hate purple in a comic book. [laughs]

SPURGEON: You're anti-purple.

COOVER: I'm

so anti-purple. I go off on these rants where I'm like, "It's a passive color!" I don't understand why all these comic book covers are purple.

SPURGEON: You know, that is sort of odd.

COOVER: Isn't it? Because purple says, "I'm hiding; I'm a shadow."

SPURGEON: It's used as a default shading sometimes, too, which is strange, because it makes it look like everything takes place in one very specific time of day. Everything is 6:53 PM.

COOVER: Everybody wants to be a

Wyeth. [laughter] Or something. Purple has its use, and that's to make yellow pop because they're complementary colors -- or to clothe

Lex Luthor, because he's a bad guy. So I have this thing about purple.

Usually when I go off on these rants I'm wearing a purple shirt, and some wiseass will say, "Well, you're wearing purple." And I'm like, "

I don't live in a comic book."

SPURGEON: [laughs] Has it been difficult to adjust to other people coloring your work?

COOVER: I've only been colored by someone else once. It was brilliant. It was

Bettie Breitweiser. For

Girl Comics. Oh my god, it was so pretty. She asked me if there was anything I didn't want her to do, and I told her not to use any purple. Apparently someone else doesn't like her using a lot of orange. I'm okay with orange, but purple is out.

SPURGEON: The figure drawing in

SPURGEON: The figure drawing in Gingerbread Girl

, and maybe this is too facile an observation, but the characters are, for the most part, good-looking people. The main ones, anyway. Is that purposeful within this story, or is that a tendency of yours given your style? Do you naturally make attractive people, or did this story call for them? Was it important to you that the characters, particularly the leads, be pleasant-looking people?

COOVER: Well, yeah. Generally, I've always found it a fault of mine that everybody's always so cute and perky. [Spurgeon laughs] You know? As an artist, you want to have a broad range. The women characters are both young and lovely; hopefully the men are meant to be attractive as well. There was a stupid stoner kid that tries to shoplift beer. I intentionally gave him pants around his ass and tried to make him a little bit more of a big nose, galumpy kind of a guy.

It's a visual form, and the character designs tell a lot about the personalities. I do tend to go more for beauties; that tends to happen naturally. So, yeah: I just indulged my own aesthetic.

SPURGEON: I wondered if there was a specific advantage here, because sometimes it can be frustrating to deal with characters that may or may not be telling the truth or not. I wondered if their being attractive might be a way past that. If we like the characters because they're attractive, nice people, then maybe we're less resentful when they start bending our minds.

COOVER: I never thought about it that way, but yeah. If they weren't people you'd want to spend time looking at, maybe people wouldn't put up with their shit as much. [laughs] If they weren't so doable. [laughter] Maybe Annah consciously or unconsciously takes advantage of that. She is being mean to her boyfriend and her girlfriend. She knows she can get away with it, at least temporarily.

SPURGEON: With the superhero monolith in comics, it seems like everyone that doesn't draw giant, muscle-bound figures gets lumped in together into their own group, where you may or may not have all that much in common. I know the Hernandez Brothers were an example for you because of how they employed their style, but I wondered about the style itself that you employ. I know that you've studied a wide range of cartoonists; is there anyone you see in your work that maybe nobody else does?

COOVER: I learned a lot from

Milton Caniff.

SPURGEON: Well, okay. My goodness.

COOVER: I know, right? For a long time I considered him one of my major influences, along with the Hernandez Brothers. They would be the people I mentioned when someone asked.

SPURGEON: Is it the way he frames panels?

COOVER: Yeah. I also studied the way he would tell stories, and even though I don't use it very much the way he uses shadow. I've been using that a little more. I've been doing some more moody, sort-of horror genre things that I'm trying to incorporate some of that. Trying to get a little bit of

[Alex] Toth in there as well.

Jaime and

Beto totally informed my work because it was one of those things where I also grew up reading Harvey and Archie comics and was obviously heavily influenced by them. They showed me how you can take that influence and apply that to more sophisticated storytelling, with

Love and Rockets. I feel that sort of funneling through

Love and Rockets made me able to do stuff like

Small Favors and then

Banana Sunday.

One of the things I'm most proud of in my own work is that my style is entirely my own. I attribute that to having read, and analyzed, and thought about so many different artists. I'm profoundly influenced by

Wendy Pini because I read

Elfquest like it was candy-covered crack. When I was a teenager, I read

Cerebus and

Love and Rockets. I read

X-Men.

SPURGEON: Something I remember from Wendy Pini's work that I might see in your work as well is the physical relationships on the page, the way characters interacted with one another. She has a nice sense of pantomime.

SPURGEON: Something I remember from Wendy Pini's work that I might see in your work as well is the physical relationships on the page, the way characters interacted with one another. She has a nice sense of pantomime.

COOVER: She had really good acting, in

Elfquest especially. I think some of her more recent stuff is a little bit more sterile -- or at least the stuff I've seen lately. I could be wrong; I haven't really examined it closely. But yeah, especially in the first

Elfquest story arc, the four volumes that were out in the '80s, the acting is

great. I was reading that really heavily [laughs] when I was 14, 15.

I think Beto has really great acting in his work as well. His cartooning is... I hate it when it's like a contest between Jaime and Beto, because there are things that appeal about both of them. But for a long time I thought Beto really spoke to me more. Especially with some of that really prime

Heartbreak Soup stuff. That really hit me. That's something that I think about a lot. I was a theater major for a little while, because all my friends were doing it [laughter] so I had to go ahead and do it, too! So I think a lot about acting and body language. I think that's a fairly common thing for cartoonists that have done a little theater.

SPURGEON: You've mentioned your own style, your sense of your style. Do you have a sense of how it's developed? Do you have an idea how it's different than it was five years ago, say?

SPURGEON: You've mentioned your own style, your sense of your style. Do you have a sense of how it's developed? Do you have an idea how it's different than it was five years ago, say?

COOVER: Oh, I do. When I first started cutting my teeth on

Small Favors, my very first few strips for

Small Favors were heavily photo-referenced. Somewhere along the line I started cartooning. Something switched. I don't know exactly what happened. I know one thing that happened is that Paul bought an original illustration by

Seth. I looked at it, and I said, "Ah-ha!" I had one of those little ah-ha moments. That occasionally happens. I remember having an ah-ha moment looking at

Usagi Yojimbo by Stan Sakai. I had a little light bulb actually go off over my head. Every once in a while I'll have one of those little ah-ha moments. It happens less frequently now, although I think that's more because it comes externally my colleagues showing me stuff rather than me analyzing work on paper.

Bit by bit, little pieces just keep adding. I swore to myself years ago that if my style becomes locked in a zone, where I feel like I have nothing more to learn, I might as well quit. I think that's when people start to suck. When they stop telling stories, and start becoming hacks, is when they feel they've learned everything there is to learn and they know exactly what they're doing.

SPURGEON: I very much enjoyed

SPURGEON: I very much enjoyed Small Favors

, but it's enough in the rearview mirror at this point I don't really have a question about the content of it. I did wonder about it as a publishing project, though. You did that pretty late in the run that Eros had. You were a latecomer in terms of the artists that put out critically well-received work in that line -- like Beto, or Molly Kiely. Was it different coming to that milieu at the end of it, as the Internet was pulverizing the bulk of the market for those books?

COOVER: I guess. I don't know. The motives for me doing

Small Favors were rather selfish. I wasn't trying to make a big statement about what a sex comic could be. I wanted to do something that would hold my attention. One of the most difficult thigns to learn about being a cartoonist is how to have discipline. I knew that would never be boring. [laughter] It was a good genre in which to do short pieces. Being able to turn out short stories on a regular basis made me feel like I had accomplished a lot.

Also, I was looking around, and I was really frustrated by the lack of female-friendly erotic comics. I felt that needed to be addressed. I wanted a comic that had a title that you could say out loud in a store [Spurgeon laughs] without having to go, "I'd like some Cum Suck Cheerleaders, please." [laughter] I wanted covers you could display on the shelves in a women's sex shop without people being scandalized. Those were my motivations. I didn't really have any sense there was a slowdown or whatever. I also wanted to do it because I felt like it would be evergreen material. It never goes bad.

I learned a lot. People often ask me, "Did you have to make a big change in your mindset when you went from working on

Small Favors to

Banana Sunday, which is all-ages?" And I was like, "No." [laughs] It's like asking if you have to adjust your personality when you go from sleeping with your spouse or walking to the store. You don't. You're the same person.

SPURGEON: The superhero material you do... it's received a lot of positive reaction, and has been covered quite a bit by writers more focused on that part of comics. The thing that interests me when someone like you with a distinctive style, a non-mainstream style, gets a hold of those characters is that the good designs seem to re-assert themselves. Do you like the superhero characters with which you've worked as designs? Did you like some more than others?

SPURGEON: The superhero material you do... it's received a lot of positive reaction, and has been covered quite a bit by writers more focused on that part of comics. The thing that interests me when someone like you with a distinctive style, a non-mainstream style, gets a hold of those characters is that the good designs seem to re-assert themselves. Do you like the superhero characters with which you've worked as designs? Did you like some more than others?

COOVER: There are certain things I won't do. I won't draw

Ms. Marvel in butt floss. [Spurgeon laughs] I just won't. I'll give her actual pants that cover her ass. [laughs] I've publicly said at Women Of Marvel panels at cons that I'm tired of the French-cut bikini and would like to retire it, please. [laughs] Given the choice I'll always default back to the

Silver and

Bronze Age designs.

SPURGEON: So you like those designs.

SPURGEON: So you like those designs.

COOVER: I think

Jack Kirby was a

brilliant designer. I really do.

[Dave] Cockrum, he had some distinctive designs. They were a little kinky, but they're fun to draw. If Jack Kirby wouldn't draw it, I stay away from it.

SPURGEON: It's been a tumultuous year for that type of comic book. I know that superhero work is still a part of your freelance profile. As a freelancer who works in that arena, when you hear about things going on in the industry -- people being fired, new initiatives taking place -- how passionate are you about paying attention to that? Do you try to work the industry, or do you just work gig to gig to gig?

COOVER: Right now I'm like gig, gig, gig for sure. In the future what I'd like to do for superhero stuff is more writing. I don't have any illusion I'm going to be the next

Jim Lee or whatever. I'm not that speedy and I'm not going to be the artist that all the fanboys want. I enjoy drawing superheroes very much. It's a personal pleasure. And the fact that there's a page rate is

great. [laughter] I enjoy a restriction. I enjoy the fact that when you're working with somebody else's characters, you have to be responsible and take care of them the way the owner wants them taken care of. You tell your story within those restrictions. I really enjoy that challenge. And I like to work. I

would like to do more writing. I'm working on my writing portfolio now. I'd like to do more longer stuff, too.

SPURGEON: Do you have a similar set of ambitions for other aspects of your working profile. What about the all-ages stuff you do? Because that is its own little sub-industry now; do you have similar professional goals?

SPURGEON: Do you have a similar set of ambitions for other aspects of your working profile. What about the all-ages stuff you do? Because that is its own little sub-industry now; do you have similar professional goals?

COOVER: I really like working with

Nate Cosby. He was my editor at Marvel for a while, and he does a lot of all-ages projects now. He's the one giving me writing work. He gave me a few writing and drawing assignments at Marvel, and now I've done a few assignments for the

Jim Henson: Storyteller anthology, and also a piece for

his Cow Boy book. He gets what all-ages really means, as opposed to "I'd love to write something stupid that kids will be able to read and that won't offend their parents." He understands you can have a complex character with problems and still have it be child-appropriate. I appreciate that. I enjoy doing all-ages stuff. I don't think I would enjoy doing stupid stuff for kids.

SPURGEON: I want to wind things down with a couple more Gingerbread Girl

questions. There's a nice sense of rhythm on the page in that book. It's clear you're not just playing around with your layouts; it seems like you're setting up specific storytelling beats. When you do a single-panel page, for example, I always feel like it's important to you that we stop and take in that page; you're not just trying to get to the next drawing. How important is a sense of storytelling rhythm to what you're trying to accomplish; how closely do you pay attention to how your work might be read?

COOVER: A lot of this stuff I worked out with Paul. He writes rhythmically. He'll write a page with 20 panels on it with one or two words in a panel: the "This is what Annah likes..." pages. Or he'll write a big splash and have it be a beat. So part of that is what I work out with him. I consciously try to know what the point of view is supposed to be. If a story is meant to be from a specific person's point of view, I don't put that character in the background, I put them in the foreground and put the focus of their attention in the background. That way, we're standing there with that chracter looking at what they're looking at. It's like sentence construction. There's a subject and an object and you have to figure out how to tell that story.

Rhythm is hugely important. I wish people would figure that out. Something happened at some point where border panels became a thing that artists stopped doing. [laughs] It made comics become this sort of rambling, "blah blah blah blah blah." [pause] That probably won't translate very well. [laughter] The first time I met

Darwyn Cooke, I shook his hand and said, "Darwyn, I'd like to thank you for bringing panel borders back."

SPURGEON: There's a lot of what I'd almost call proscenium work in

SPURGEON: There's a lot of what I'd almost call proscenium work in Gingerbread Girl

, where you have people in the direct foreground interacting with the reader. At the same time, there are plenty of panels with loaded backgrounds and depth, and you do get the sense of a changing camera; it's not static at all. That seems to me two wildly different approaches. Is it hard to get multiples ways of approaching a scene to work on the same comics page?

COOVER: There's a lot of comic book specific iconography in

Gingerbread Girl, like the rebuses or the fantasy panels where it's a visual representation of concepts. Like where Annah's personality is sucking up Ginger, and all of these Gingers are being sucked in. That's a very comic booky thing; that wouldn't really work in another medium. So I think it's just whatever was appropriate to that part of the story.

SPURGEON: So we know what you were

SPURGEON: So we know what you were trying

to do. But did serializing Gingerbread Girl

on-line have the intended effects?

COOVER: I think it did. It's a scary thing to plop $13 down on 120 pages of something you don't know what it is -- especially where the artist and writer are going, "I don't know what it's about, really." [laughter] So the best thing to do is to say, "Here's what it is." And let people make that decision for themselves. And it did. It got a lot of buzz, at least in the parts of the Internet I looked at. It's gotten a little bit more buzz this week.

Someone on Think Progress was analyzing it in terms of mental health and fiction. That was pretty cool.

SPURGEON: You're off to that medical conference on comics, Colleen. [Coover laughs] I can feel it.

COOVER: The book came about when Paul was reading a book on neuroscience that he picked up for free when he was working at

Powell's Books. He read about

the Penfield homunculus, the concept of it, and went, "Hmm. That's an interesting notion. I'll write a story."

*****

*

Colleen Coover

*

Gingerbread Girl

*****

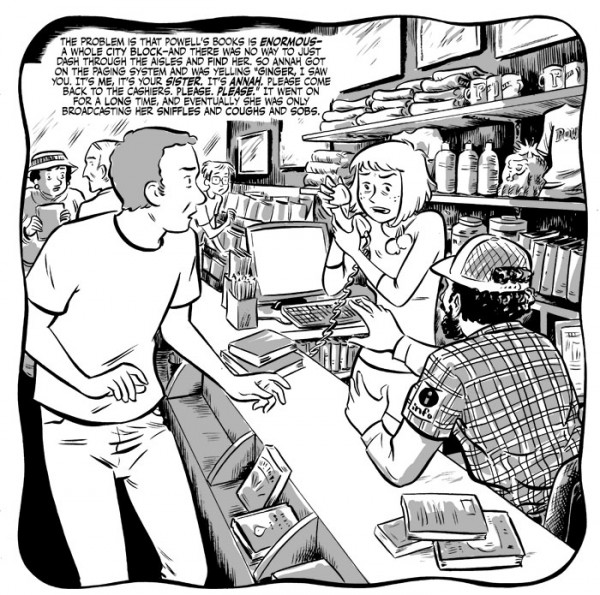

* arresting single-page image from

Gingerbread Girl

* photo by me, I think

*

Banana Sunday single-issue cover

* Nick and Nora Charles (and Asta)

* cover to

Gingerbread Girl

* panel from

Gingerbread Girl

* the four-panel grid used in

Gingerbread Girl

* the basic approach to the single color in

Gingerbread Girl

* Coover's work looks nice in color

* cute

* not-so-cute

* a Wendy Pini-style silent moment; that could be Cutter and Skywise, I swear

* a panel loaded with depth and detail

* a

Small Favors cover

* a superhero page

* another superhero drawing

* from that

Storyteller collection

* what I would call "a proscenium approach"

* a very comic book type of effect

* a drawing in ink and wash (below)

*****

*****

*****