Home > CR Interviews

Home > CR Interviews CR Sunday Interview: Tom Gauld

posted April 2, 2012

CR Sunday Interview: Tom Gauld

posted April 2, 2012

I've been a big fan of the cartoonist

Tom Gauld for several years now, devouring the bits and pieces of the Scottish-born artist's comics and illustration work that makes it to our shores and snapping up any and all publications in which that work appears. Gauld makes comics in a lot of the minor-key ways, many of which were also utilized by influence

Edward Gorey: an almost textural feel to individual images, startling contrasts in terms of size of figures and narrative elements, a casual reduction of visual keys into a more rudimentary drawing style, incremental changes in design elements from panel to panel. I got in the habit of reading Tom Gauld whether he was appearing in an oversized, lavish book from an outfit like

Buenaventura Press or on the backs of postcards I want to keep but have to share.

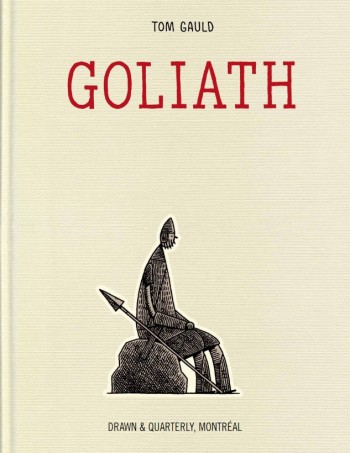

Gauld's latest is

Goliath, a full-length book project from

Drawn and Quarterly that in ways he describes below has been in the works for over seven years. It's his longest narrative to date, and distinguishes itself for the smart execution of what in other hands could be an overly-clever, high-concept exercise: the story of

David and Goliath told from the perspective of

Goliath. Gauld uses several design elements to fine effect here, but the heart of the book can be found in the lonely landscape he depicts and the lonelier main figure he places in its midst. I think it's an accessible work, too, the kind you pass on. I hope that by interviewing Tom Gauld several of you might consider the book when it comes out in a few weeks, and that some of you in an ordering capacity might take an extra look. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: One thing that intrigues me about your comics-reading past is that you claim to have been a British comics-only kind of kid. How do you think you're a different artist for having that specific reading experience? Do you still value anything you learned from reading Battle and 2000 AD?

TOM GAULD: It's true that I never got into mainstream American comics as a kid, but I did read

Asterix and

Tintin a lot. Our local paper started running

The Far Side and I loved that and

[Gary] Larson inspired me a great deal.

But to answer your question, I think maybe the science fiction and black humour of

2000 AD fed into my work.

Probably more importantly

Battle led me into reading

2000 AD which led me into reading

Deadline which got me interested in alternative comics generally.

SPURGEON: You've said that you discovered you could actually do comics and cartoons for a living while in art school; do you remember how you figured that out, and what the effect of suddenly having that possibility open up for you was like?

GAULD: Before I went to art school (

Edinburgh College of Art) I thought I'd have to do something like graphic design to earn a living, but when I got there I tried the illustration course (in the first year you did a bit of everything) and realised if I did that I could just draw all the time. That really appealed to me, there were/are aspects of design, painting and making things that I liked but it was drawing that I really loved. At Edinburgh I was mainly doing illustrations but towards the end I started making more narrative work then sort of ran out of time to do what I wanted, so I applied to study for two more years at

The Royal College of Art in London. That's when I really got into making comics, the course was really open and I had lots of time to do my own thing, my tutors and fellow students were really encouraging. I also met

Simone Lia there and we made our first comic (called

First).

SPURGEON: How much do your comics reflect things that you learned in art school? What are some things you think you might do differently for having what sounds like some extensive training?

GAULD: Both the art schools I was at were very relaxed, there were sometimes briefs to work to and drawing classes but most of the time we were left to do what interested us. I spent a lot of time doodling, in the library and going to the cinema. Without all that time I might well not have started drawing comics at all. I'm very into the design of my books and I think that interest comes from my time at art school.

SPURGEON: You're obviously influenced by Edward Gorey, but your work lacks his camp sensibility; in fact, I think the influence is mostly felt visually. Can you talk about how you discovered Edward Gorey, why his work is important to you? He's such a massive influence on cartoonists but he's also one of those guys like B. Kliban that's not all the way seen as a comics maker.

SPURGEON: You're obviously influenced by Edward Gorey, but your work lacks his camp sensibility; in fact, I think the influence is mostly felt visually. Can you talk about how you discovered Edward Gorey, why his work is important to you? He's such a massive influence on cartoonists but he's also one of those guys like B. Kliban that's not all the way seen as a comics maker.

GAULD: I discovered Gorey's work in the college library when I was at Edinburgh and I was immediately fascinated by it. I think it was the atmosphere in particular which attracted me, the idea of opening these little books and going into his imagined, self-contained worlds. I like the design of his books, you've started going into his world as soon as you see the cover. The restrained drawings, deadpan/black humour and mock seriousness all appeal to me too.

For a while at college I was just copying Gorey, but then as I made more work I did more my own thing, though I still crosshatch like he did.

I didn't know B. Kliban till you mentioned him here. I've just been looking at his work which is great, thanks for that!

SPURGEON: [laughs] You're welcome.

There's a tension in your work between atmospherics and foregrounded action. You have a very filmic sense of atmosphere, and mood; the worlds you create are very palpably yours; at the same time, a lot of your work, especially the early stuff, is very reminiscent of theater in the way you craft dialogue and you focus on interactions between your characters. Is it fair for me to say that you're interested in both of these elements? How much is the feel of a work important to you?

GAULD: Yes, I'd agree with that. I find that when I'm drawing I'm quite happy to come up with larger than life, epic things but when I write things tend to be more down to earth. The contrast between greatness and everyday reality is something which interests me.

Atmosphere is very important to me. None of my comics are set in the real world and I want the reader to feel they are somewhere else.

SPURGEON: How natural was it for you to do your clean-up and color on computer? I think of you as being just about the age where that would come absolutely naturally. Is there a part of comics making you'd never consider taking to the computer?

SPURGEON: How natural was it for you to do your clean-up and color on computer? I think of you as being just about the age where that would come absolutely naturally. Is there a part of comics making you'd never consider taking to the computer?

GAULD: I learned how to use photoshop mainly because I wanted to print comics while I was at college and you had to pay for photocopies whereas the laser printer was free. As I got more into it I realized it was the perfect way for me to do color. Partly because I'm not very good with color so I can fiddle around till I get something I like and as I'm a bit colorblind I can check the CMYK values and be sure the colors are what I think they are. Also I do like the clean, flat coloring you get with a computer.

These days I scan in and fiddle around with my pencil drawings in photoshop quite a lot to get them how I want them before I print them out and trace them on a lightbox in ink. So a computer is used quite a lot in my process, but I can't see myself stopping doing pencils and inks by hand for a while. But I'd never say never, if the technology seemed right I'd at least try it.

SPURGEON: How much does having published your own work, even on a limited scale, have an effect on how you approach publishers? For example, are you harder on publishers for the option of doing something yourself, or are you easier on them because you need how rough a big that might be? What does a successful publishing relationship entail in order to satisfy you?

GAULD: I hope that having self-published makes me more realistic about what a publisher can do for me, and hopefully a bit easier to deal with. With self-publishing I love working on the design and production but I have very little interest in sales and distribution, so for me a good publisher gets me involved in the former and takes care of the latter. Drawn and Quarterly and previously Buenaventura were both very much "tell us how you want it and we'll try to do that."

SPURGEON: When you're involved with a publisher like that, how deep does that involvement go? Where would your influence be most directly felt? Book size, paper stock, the overall look, how you're doing color and shading? How important are these production to the final book for you? Given complete control, how much would you manage those elements of a work?

GAULD: I'm interested in all those elements. Initially I intended

Goliath to be black and white but as I worked on it I realised it needed something more and asked D&Q if it was ok to use a second colour which they were fine about.

I'm not sure how the other artists at D&Q work, but I had clear ideas about all the elements of the book design and they seemed happy to go with those and offer some good suggestions on improvements.

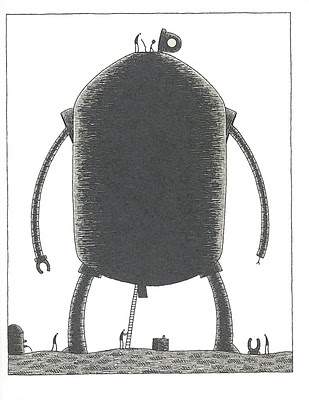

SPURGEON: Tell me more about working with Alvin [Buenaventura] and Buenaventura Press. Hunter and Painter seemed to be an extension of some of the work you had been doing -- these kind of comic dialogues held across some sort of abstracted space -- but The Giant Robot seemed more an expression of maybe your printmaking side. Is that a fair assessment? What was the thinking behind the series of static images that make up

SPURGEON: Tell me more about working with Alvin [Buenaventura] and Buenaventura Press. Hunter and Painter seemed to be an extension of some of the work you had been doing -- these kind of comic dialogues held across some sort of abstracted space -- but The Giant Robot seemed more an expression of maybe your printmaking side. Is that a fair assessment? What was the thinking behind the series of static images that make up Giant Robot

, the idea of a comic whose transitions emphasize time over space? It's something that pops up in your work quite a bit. Was there a particular kind of project you thought BP did well?

GAULD: The idea came from a cartoon I did for the

Guardian and I thought it would make a funny/sad narrative to see this thing -- initially a sculpture but then I changed it to a robot -- which was grand and full of potential to just fall away to nothing.

I like repeating images with small changes to tell the story, and this took that to an extreme. I suppose this was more about the idea and the drawings than a narrative.

I think Buenaventura were good at making that sort of slightly odd thing which is still in the world of comics, but a bit art book-ish, too.

SPURGEON: Let me jump back a bit. The Move To The City strip -- your drawing seems less refined there, in a sense, but the page layouts and the structure of the story seems more complex than some of your earliest work. Was that an important work in terms of you trying out new things? What do you remember about doing that work now?

GAULD: Move to the City appeared weekly in

Timeout London for about a year (2001-2002 ish). I'd just finished college and went to see them with my portfolio, they really liked

Guardians of the Kingdom and asked if I could turn it into a weekly strip. It was great getting a weekly paying job at that time. The idea was very simple and I tried to play around with layouts and different ideas within that as much as I could. Looking back at it there are some parts which make me wince, but it was a good learning experience.

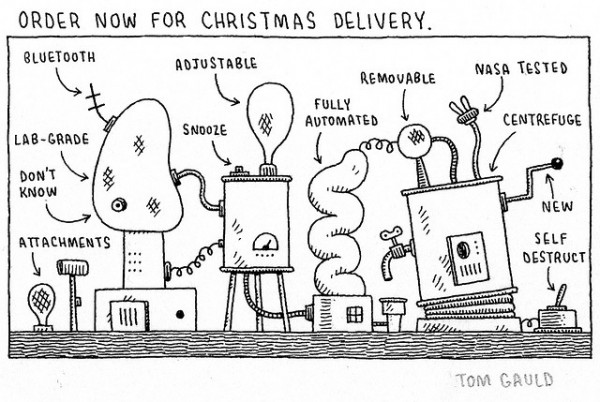

SPURGEON: How did your current gig with the Guardian settle into the recurring space in the

SPURGEON: How did your current gig with the Guardian settle into the recurring space in the Saturday Review

letters section? My understanding is you went from irregular cartoons to these more regular ones. Those are essentially gag strips; how do the gags develop in terms of the writing of them? Are they positively received? I'm trying to figure out if that would be the kind of audience amenable to having a cartoon on that general subject or an audience hostile to how you treat the general subject matters involved.

GAULD: The art director at

The Guardian Review is

Roger Browning, who is a great guy. He hired me to do occasional illustrations and cartoons straight out of college then when the cartoon spot on the letters page opened up he asked me to do that. I'ver been doing it for six years and it's been a really good experience. I've learned a lot from it, for example from having a tight turnaround and having to keep to such a small space.

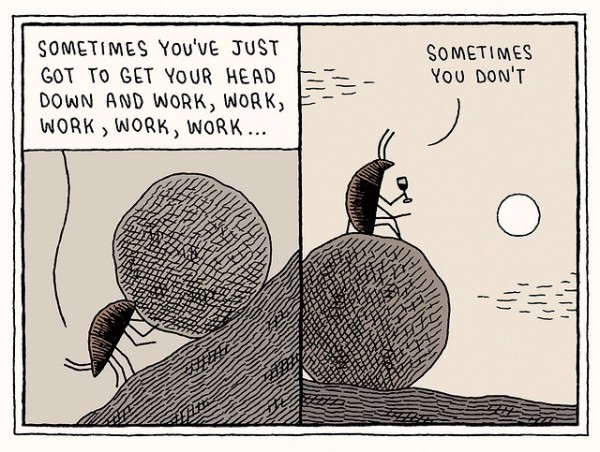

On Tueday afternoons I get sent the lead letter for the page and I have to take that as my theme then I sit and doodle in my sketchbook 'til I come up with something. I try to look at the theme -- almost always something to do with the arts -- from an unusual angle, or juxtapose unexpected things. Then I have most of Wednesday to draw it up.

It's interesting being forced to come up with something for a deadline like that: some weeks I might have to go with what I think is a mediocre idea but then sometimes -- though not always -- when I've finished I look at it and realize it was actually good idea.

The reception to the cartoon has been really nice. I think everyone realizes that most of the time I'm making fun of things that I love too, and even when I might be more critical it's quite gentle teasing.

SPURGEON: Did

SPURGEON: Did Goliath

come out of a desire to do a longer, more involved piece? I see some hints in past interviews that you maybe wanted to try something of greater length at some point. Did the idea develop before, after or independently of the idea of doing a book with D+Q?

GAULD: I've been wanting to do a longer piece for quite a while, but since I spend most of my time working as an illustrator and squeeze comics in around that, it was hard to find the time to concentrate on one. In 2005, I wrote to D+Q and asked if they'd publish a book if I wrote one and they said yes so I signed a contract to do a book. I thought that if I agreed to do one for a publisher it would spur me on to get it done but things kept getting in the way: I had two children just after that, I was busy with illustration work and I was also quite daunted by the prospect of making a longer comic and couldn't settle on an idea. In the end I didn't properly start work on

Goliath till 2009.

SPURGEON: For that matter, how did you end up working with Drawn and Quarterly? Their focus seems to be in a slightly different place than a lot of your works have been over the years. There also seem to be any number of publishers for art comics and graphic novels in Great Britain now. Was there something about their catalog that had a specific appeal? Something they did well? Do you feel an artistic kinship with the other cartoonists on their publishing slate?

GAULD: I went to D&Q because I love their books, they seemed good with stories and design. The stuff they were publishing by

Sammy Harkham,

Kevin Huizenga and

Anders Nilsen felt like work which mine would fit in with, in some way or other.I'm speaking in the past tense as I made the decision to go to them seven years ago, but I'd make the same choice today.

As for British publishers there are some great publishers around now, it feels like a real boom, which is fantastic, but either they weren't around or I didn't know about most of them till the last few years.

SPURGEON: Goliath is one of those iconic characters, but he's may not be the most iconic even of his type in the Bible -- that would probably be Samson. Why Goliath? The twist you provide the character is strong and fairly straight-forward, but I'm interested in what struck you about the character or his situation that you wanted to work with him at all.

GAULD: I wanted to make a story about a giant, I started a story about a giant being hidden away by his family to avoid being called up by the army then abandoned it. Then I made a story for

Kramers Ergot Vol. 7 about

Noah and got thinking about other Bible stories I could work with.

When I read the Goliath story in the Bible I realized how little it said about him: basically just a description of his height, weapons and armour, his challenge and a short dialogue with David. So there was space for me to make my story in. I liked the idea that David's triumph is Goliath's tragedy.

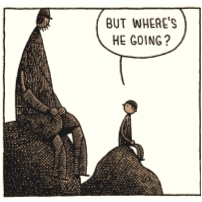

SPURGEON: I love the kid foil for Goliath, but he's not a full partner the way that some of your characters have been in past works. Was there something you hoped to draw out of the story for having that particular character serve as a kind of witness for what's going on?

SPURGEON: I love the kid foil for Goliath, but he's not a full partner the way that some of your characters have been in past works. Was there something you hoped to draw out of the story for having that particular character serve as a kind of witness for what's going on?

GAULD: I wanted all the elements in the Bible version of Goliath to be in my version too, but the fact that he had a shield-bearer was a problem at first. I wanted Goliath to become isolated and lonely in the valley, but if he had a colleague that wouldn't really happen, and having two equals stuck out there felt like something I'd done before. When I figured out that the shield-bearer could be a little boy it solved that problem and he seemed to work well in the rest of the story. I'm not sure exactly why, but he just felt right.

SPURGEON: You've satirized war before, and its theatrical aspects and the cynicism behind some of the ploys -- this work seems to be more directly tragic in terms of our getting to know this one particular character and your not maintaining a satirist's distance but portraying his kind of settling into this strange role. Were you happy with this work as a character study?

GAULD: I wanted to push my work on a bit with Goliath, but still keep to the things which interest me. I think its inevitable that in a longer piece, where we -- me and the reader -- are spending more time with a character, that things work out differently than in a short piece. Yes, I'm pretty happy with it.

SPURGEON: I wanted to ask you about two artistic elements of

SPURGEON: I wanted to ask you about two artistic elements of Goliath

, just get your general thoughts on how you worked them into the story. Why did you change the lettering on things like Goliath's declaration and with David?

GAULD: I use the serif lettering whenever the text is quoted from the bible. It's intended to be a bit of an ominous reminder of where he's inevitably headed. When Goliath speaks his declaration for the first time it's in that style to suggest that it's not natural to him, that he's being manipulated into the role by what he's been forced to read out, as time goes on and he settles into the role he starts just saying it like anything else.

At the end when David appears talking in King James Bible quotes in serif I wanted it to feel like he's not there just as a person, he's an unstoppable force of nature, or God. Or as if he's part of a bigger story which has overpowered Goliath's story.

SPURGEON: The use of shading and darker panels; how much of that was a design consideration, just how it looked on the page, and how much of that was used by you to convey specific changes in mood?

SPURGEON: The use of shading and darker panels; how much of that was a design consideration, just how it looked on the page, and how much of that was used by you to convey specific changes in mood?

GAULD: It was initially a design decision, but once I had it I tried to use it to convey atmosphere.

SPURGEON: Moving forward, how much ambition do you have in terms of the longer narrative side of your artistic output? Will we see more books. And when will we get that big Tom Gauld collection?

GAULD: I'm working on some shorter things right at the moment, but I'd like to do another long narrative. I feel I took quite a few wrong turns before settling on how to do

Goliath, so I hope from what I've learned I can make another one without taking so long.

I'm definitely going to put together a collection of shorter pieces at some point; I'll keep you posted.

*****

*

Goliath, Tom Gauld, Drawn and Quarterly, hardcover, 96 pages, 9781770460652, 2012, $19.95.

*****

* cover image to the new book

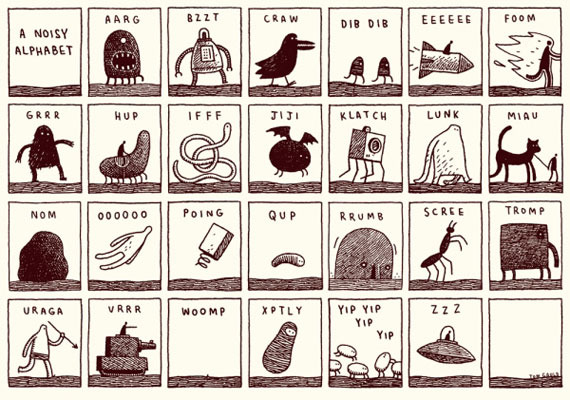

* two stand-alone cartoon images by Gauld

* from

The Giant Robot

* a

Guardian Saturday Review letters page cartoon

* a page from

Goliath

* the kid foil

* biblical lettering in

Goliath

* another moody page from

Goliath

* I just like this little sequence; there's no real reason it's here (below)

*****

*****

*****