Home > CR Interviews

Home > CR Interviews CR Sunday Interview: Thomas Scioli

posted April 9, 2012

CR Sunday Interview: Thomas Scioli

posted April 9, 2012

*****

Thomas Scioli

Thomas Scioli recently released

a print version of his

American Barbarian through AdHouse. Like much of what audiences have come to expect from the artist, who turns 36 this week,

American Barbarian is a song sung in the key of

Jack Kirby with lyrics, shadings and major solos all Scioli's own. I thought it a blast, and I wanted to ask the prolific cartoonist about various elements of its creation. He was nice enough to write back. Like all of my interactions with Scioli, I found him earnest and possessed of a great deal of clarity when it comes to talking about what goes into his art.

I hope that you'll consider

American Barbarian among your major comics purchases for this richer-than-usual winter comics shopping season. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: The last time we talked was 2008, when you and Joe Casey had just announced you'd be winding down on Gødland. At the time you both intimated it would end with #36, although you left yourself some wiggle room. Is that still the plan?

THOMAS SCIOLI: It's ending with #37. I'm drawing #36 now.

SPURGEON: What has taken up the bulk of your time since that wind-down? I know in 2008 you talked about returning to your own series, but I'm not sure how much of that work has come out.

SPURGEON: What has taken up the bulk of your time since that wind-down? I know in 2008 you talked about returning to your own series, but I'm not sure how much of that work has come out.

SCIOLI: I put out a

Myth Of 8-Opus OGN and some minicomics, did

Gødland #25-35,

a Captain America issue and

American Barbarian. I did some other things here and there and a lot of non-comics freelance work.

SPURGEON: You also back in 2008 expressed maybe a bit of frustration about what sold in the marketplace, and how tough it had become for newer comics work. Do you still have concerns about finding a place in the market as currently constituted?

SCIOLI: No. Webcomics are the solution to that problem. I wouldn't launch a new series in comic book form. I'd serialize it as a webcomic, then put out the collection. That's what I did with

American Barbarian. Building an audience with a monthly print comic doesn't make any sense to me any more.

SPURGEON: Let me ask a bit about building that audience... would you characterize how big of an audience you were able to build serializing on-line? Was there anything specific you learned about that model in putting it into practice, anything you'd care to pass along to a cartoonist thinking about taking that particular plunge?

SPURGEON: Let me ask a bit about building that audience... would you characterize how big of an audience you were able to build serializing on-line? Was there anything specific you learned about that model in putting it into practice, anything you'd care to pass along to a cartoonist thinking about taking that particular plunge?

SCIOLI: It's hard to gauge how many people that amounts to. You're an old pro at digital publishing, do you know of a website or software that helps you translate those Google analytics figures into some kind of number to tell you how many people are reading it?

SPURGEON: No.

SCIOLI: I know it's bigger than the number of people who bought copies of my serialized print comics. About five times as many readers? Something like that. I think the difference is the level of attachment. People can read the entire thing and figure out if they like it or not before being asked to pay for it. I feel like I've grown a whole new audience pretty much from nothing and I plan to continue to build on that with each new work.

Before I started this book, I felt like I was at the end of my career, that it had run its course. This project saved me. It made me excited about comics again, and it was only possible because of the webcomics format.

I guess a piece of advice is, there's more to comics than just words and pictures. When you think about the great comics, how many of them were the height of great writing, or the pinnacle of finely-crafted art? I'd argue most of the great comics were not. Their greatness was in an intangible quality that existed apart from those two very obvious craft elements. Try to work less in those two areas and more in that third area. That's where the reader lives. They're not living in the craft, they're living in the holistic experience.

Dare to be self-indulgent. Comics take a lot of hours of a cartoonist's life. Make sure you enjoy those hours. That enjoyment will carry over to your audience. The hard work is the amount of time you're sitting at the drawing table. The things you draw should be whatever you want to draw.

I'd advise not allowing yourself to be too limited by what you think will work for print. That said, you should keep the print version in mind. Don't obsess over it, but don't paint yourself into a corner.

This is specific to the form that webcomics exists in at this moment, but I think a good general bit of advice is to be open to new formats. Things change with increasing rapidity, and you want to be aware of it and be willing to do the work it takes to make those jumps. Each change in technology is an obstacle that could take you out of the game if you don't adapt to it.

SPURGEON: I know that Gødland -- at least the visuals -- developed out of your sketchbooks and what Joe Casey reacted to in them. How did American Barbarian

develop? Is it also a matter of working with material you're constantly designing, or are there elements of problem-solving moving from a story or story idea into a design?

SCIOLI: It came out of sketchbooks very gradually. It was something that I worked at on the side little by little. I put together a series of post-it notes with various moments. Assembled it into an eight-page story. It wasn't exactly what I wanted. I decided to change up my process and wanted to write it like I imagine

Alan Moore writing. I got a notebook and made 12 chapters, each chapter pertaining to a month of the year. I free associated about what each month means and wrote down every association I could think of. I took those elements and added events and incidents that related to each month. I kept refining this and ended up with a 12-chapter story that had a lot of incidents, but no through line connecting it. Then one night, my mind wandered and all those incidents rearranged and assembled themselves along the spine of a basic revenge story. It was more or less the complete American Barbarian story as it is published. So although things came together seemingly by magic, it was at the end of a long organized working process.

SPURGEON: Is this your most ambitious project, do you think? I know that the work is split into chapter, but it's pretty much conceived as a one-off. Was that different for you in terms of writing and executing the project?

SCIOLI: 8-Opus and

Gødland were more ambitious, but it was an ambition of ignorance. I didn't realize what I was signing myself up for. I didn't realize how grueling it would be working on multi-volume, multi-year series, and had I known, I would've embarked on something much shorter.

Now, having a better idea of what I'm capable of,

American Barbarian is my most ambitious project. I'm a little bit afraid that it might be the best comic I ever do. I hope I make something better, but it definitely feels like a culmination of everything that came before it. If ambition is connected to page count, I don't see myself having the energy to try another book this length.

Everything I'd done prior to this was intended to be vast epics that ran for years. I'd have general ideas of where I wanted to go, but I'd just kind of meander. With this I wanted to have everything more or less figured out before I started drawing. And I wanted to draw it in about a year. it took me a year and a half to draw it. I was tired of working on things that ran for years and years with no end in sight. That used to be the thing I aspired to, but I've found the negatives outweigh the positives. For me, I can only work on a project for so long before I start running out of steam.

American Barbarian was the perfect length. Long enough to be a satisfying epic journey, but short enough that I could actually complete it without totally burning out on the concept.

SPURGEON: What about working with AdHouse appealed to you? I know that small publishers are notoriously hands-off generally, at least for the most part, but I wondered how it might have been different working with Chris [Pitzer] -- who has, for instance, a strong design sense -- and some of the other folks with whom you're published.

SCIOLI: The book was close to completion by the time we decided to work together so I don't know how much any publisher would've been able to contribute to the project. What I wanted from a publisher was good book design and a commitment to the project. I knew the book would look good with AdHouse. Great attention to detail. I also have the impression that he's got experience getting books placed in places beyond just comic stores. Chris was a fan of the book, too. He was genuinely excited to work on it. That was important to me.

SPURGEON: How do you set the general tone in a work like American Barbarian

? Because there are design elements and parts of the story that could be seen as so outrageous they're humorous, or even self-lacerating, but I also don't get the sense you see those things that way at all. Is there a line you're conscious of in terms of being too wild, or do you feel when you're working with something like this you're better off going out as far as you can in terms of story elements and parts of the visuals?

SCIOLI: There's nothing that's too wild. I made the decision a long time ago that in order to make good adventure comics you can't be afraid to look dumb.

I think tonally the closest thing to this comic is

the Rodriguez and Tarantino double feature GrindHouse. That film was a turning point for me as far as how I thought about my work. Hitting the beats of the genre, but also trying to make something transcendent out of junk. And the laughs in this are like the laughs in

Grindhouse where it's a loud grunt of shocked surprise.

I don't think self-restraint on my part would do anybody any favors. If I have a line, it's an aesthetic one. I wouldn't put in something that I find visually unappealing.

SPURGEON: A couple of specific creative choices jumped out at me. First, I love the name "Two-Tank Omen." Do you remember specifically from where that one came? Second, the visual of American Barbarian literally spelling out his overall aims on his hands where he could see them... how did that strike you that you wanted to pay attention to that specific image?

SPURGEON: A couple of specific creative choices jumped out at me. First, I love the name "Two-Tank Omen." Do you remember specifically from where that one came? Second, the visual of American Barbarian literally spelling out his overall aims on his hands where he could see them... how did that strike you that you wanted to pay attention to that specific image?

SCIOLI: Those are two good examples, because they came from very different processes. Two-Tank Omen appeared to me in a dream. It's the kind of word play I like to do, so it definitely fit. The thing with American Barbarian's hands came to me in a semi-meditative state. I don't practice meditation or anything, but I find myself occasionally entering a state of mind similar to what people who practice meditation describe. I enter those states either just before falling asleep, or on long car rides. In this particular case it was while reading an entertaining, yet not-very-demanding book. So as I'm reading a junky book with one part of my brain, another part of my brain was wandering. That's where a lot of the threads came together. That sequence came fully formed, but in retrospect I can see where the pieces came from. But it's maybe a little disingenuous to describe the components because it's not like I sat down and put them together piece by piece. It came to me fully formed and I was, after the fact, able to see where it came from, but it was an unconscious process that came from being open to inspiration.

There's something that's typical in revenge narratives where the hero writes a vow to whoever he's going to avenge. You see it a lot in silent movies. Sometimes it's written on a wooden headstone in a hastily-dug grave. The "note-to-self." There's also the component of Kirby-style comics, and action comics in general, being obsessed with the hands. The triple exclamation point drives home the Kirby link. There's the violent self-punishing nature of revenge.

Stigmata. The physical reminder of pain that could be referenced again and again through the story.

SPURGEON: Tom, the look of the piece, the color and shading I think is very striking. You do this wonderful thing of putting these strident, strong colors against more basic backgrounds, and setting off specific elements -- like American Barbarian's hair and the other red/white/blue images -- against those single-color images. How much development was there in terms of how you were going to approach color, and are you happy with the specific events you were able to achieve?

SPURGEON: Tom, the look of the piece, the color and shading I think is very striking. You do this wonderful thing of putting these strident, strong colors against more basic backgrounds, and setting off specific elements -- like American Barbarian's hair and the other red/white/blue images -- against those single-color images. How much development was there in terms of how you were going to approach color, and are you happy with the specific events you were able to achieve?

SCIOLI: I was very happy with the end result. Color was the starting point of this comic. I wanted to have some sort of striking visual that exists entirely apart from the black plate. In its earliest phases, the book was "Rainbow Barbarian." The red-white-and-blue motif is what I settled on.

I've had plenty of time to think about color. For most of my life I learned to work in black and white. When I made the jump to color comics, working with colorists, I had so much to learn. It forces you to think about your drawings in a different way. I was reacting to the way my work was being colored and adjusted to it. I started coloring more and more of my own work. It was incredibly difficult. I didn't like what it looked like. By the time I started

American Barbarian I decided to settle on a limited palette of my favorite colors on everything I'd done up until that point. I decided since I was going to color it myself, I could leave a lot of open areas in the black plate and still be able to communicate what I wanted to.

The black plate in modern comics is so deep and rich and stark that it separates itself from the rest of the colors. It's like the black plate is way up in your face and the colors are way way way in the background. The way most artists deal with this is to make the lines in their black plate very thin. I have a heavy hand. I like a bold application of ink, but it's too much if you print it as a cmyk black. I eliminated the black plate and found a color that's dark enough to read as the main line, but soft enough that it's within the same range as the other colors. That's made all the difference. The line that we've seen throughout the history of comics up until the '90s isn't a black line. It's a scabrous, skin-cancer dark brown. I wanted to find a line color that held the art together the way that line does, but is a more pleasing color, so I settled on a deep deep green. I feel like my color work finally looks right. It's taken a long time to find my way here. If you'll notice in the webcomic I start with a standard black line then part of the way through I discovered that green line. If I had done this as a monthly comic book, I would've stuck with the black line throughout, so it's another benefit of test-driving it in webcomics form.

SPURGEON: One of the more exciting visual flourishes I think came early on: the first approach of Two Tank Omen as a kind of rising tide on the page, crowding out the standard narrative. I really liked that; can you talk about what you were trying to achieve there, and where that might have originated? How confident are you in tweaking page design like that?

SPURGEON: One of the more exciting visual flourishes I think came early on: the first approach of Two Tank Omen as a kind of rising tide on the page, crowding out the standard narrative. I really liked that; can you talk about what you were trying to achieve there, and where that might have originated? How confident are you in tweaking page design like that?

SCIOLI: Sometimes I'll have an idea for a visual flourish or a sequence and no place to use it. I'll have layout techniques, panel arrangements that I'll jot down for future use. There's the age old comics thing of a page where you have the main strip at the top, then a second supporting strip at the bottom. I had the idea of having a sequence of pages where the secondary strip gets larger and larger until it takes over the strip above it. Years later I found a use for that concept in

American Barbarian. I think that's an important part of the creative process, to store up tricks in hopes that one day you'll find the perfect place for them.

SPURGEON: Another very bold choice you make at certain times is to use a different art technique within the narrative -- like a photo panel, or dropping the hard lines for a more rounded effect where the shapes are emphasized? Is that just playfulness on your part, a way to spice up the story visually and keep it interesting for you, or does each of those instances speak to a specific solution to a problem you saw on the page?

SPURGEON: Another very bold choice you make at certain times is to use a different art technique within the narrative -- like a photo panel, or dropping the hard lines for a more rounded effect where the shapes are emphasized? Is that just playfulness on your part, a way to spice up the story visually and keep it interesting for you, or does each of those instances speak to a specific solution to a problem you saw on the page?

SCIOLI: A splash page or a double splash used to be the showstopper in a comic. Now they're rather commonplace, so to really freeze the moments you want to highlight, you need to do something different. Radically changing the drawing style or switching media is an easy one. There used to be the fear that you need to be consistent to keep the reader with you, but that's just not the case. The reader will follow whatever images you string together and make some sort of sense of them. You'd have to come up with something really jarring to totally lose them. So there's no fear really.

I thought that this project could be a transitional work, where I incorporate more tonal work throughout as accents, as show-stoppers, then by the time I was finished with this, I could do purely tonal drawing in my comics. Once you start coloring your own work, you can't help looking at everything differently. The tone drawings/paintings take about as long as penciling, inking, erasing, coloring. Some of the pages I knew from early on I wanted to paint, some I just woke up that morning in the mood to paint something. I feel like in a future project I could alternate between line drawing and tone every panel, for a 1-2-1-2 rhythm.

SPURGEON: I know that in Kirby's work on Kamandi, elements of modern culture appear in these future settings so that he can make a point about specific elements involved in those cultural constructs but also to make the point, it seems, that the future may echo those thing in a kind of fallen state. Do you include things like the lottery, say, to make a point about the lottery, or as a kind of homage to folding in that kind of element into this kind of story? I realize I may be over-thinking this in very dramatic fashion, but I wonder how you decided what to include and what not to include that could be taken as satire and commentary.

SCIOLI: I assumed once I put the word "American" in there, it could be read as some kind of commentary. I think the kind of commentary is similar to some of the things in

Kamandi in that it's not a direct commentary, but comes at things sideways, taking bits and pieces and assembling them in a way that's meaningful for the purposes of telling a good story, and whether or not they resonate as a statement is secondary. I spent a lot of time building a bank of story bits and then found a place for them later on in the process as the story took shape. The lottery was one such instance. It's kind of like Kirby's approach to mythology. There's a willful deliberate misunderstanding of existing mythology that he used to build his own mythology. That same kind of thinking, deliberately jumbling elements from current events and popular culture, to create something resonant and compelling.

I lived this book. It took over a years to slowly spool out the story. It probably took you about an hour to experience this story, for me it was in slow motion stretched out as I wrote, drew, colored. I know all the seams. There are parts of this story that are very important to me, very serious. There are parts that are an afterthought, or parts that come part and parcel with the genre, preloaded. At least as far as the idea of a society that picks members to feed a monster. It goes back to

Theseus and the Minotaur. The idea of a lottery where the prize is death is a genre staple. Giving it the shape of the modern lotto with the popping ping pong balls seemed a natural flourish.

SPURGEON: I thought your Angouleme diary was very interesting in that you pointed out how disreputable the comics you read as a kid were for European readers of that material. Did that perspective cause you to think of those comics in a different way, or was that just generally curious to you, that reaction?

SPURGEON: I thought your Angouleme diary was very interesting in that you pointed out how disreputable the comics you read as a kid were for European readers of that material. Did that perspective cause you to think of those comics in a different way, or was that just generally curious to you, that reaction?

SCIOLI: I think about comics in so many different ways.

As someone who has spent a life obsessed with comics, specifically superhero/scifi/fantasy comics, there's part of me that thinks they probably are poison. The superhero genre has so much toxic shit in its DNA. I'm able to love it and work in it because my focus is on the spectacle, the surface elements, the color, the psychedelia, but when you get to what's thematically at the heart of it, it's ugly.

These interviews are tough because sometimes I wake up in the morning and it's "Yay Comics!" and sometimes I wake up and feel like it's this awful destructive thing. Probably fixating on anything to the degree that I fixate on comics would be the same.

You probably feel it even more than I do. I just read and focus on the comics that interest me. You, as a journalist, have to give a lot of attention to things that you would run from otherwise. You've got to hate comics at this point, right? Or is there a point where that energy turns into something else?

I've always been interested in how people react to Kirby. I had such a strong specific reaction to Kirby's work, that I assumed everyone else would feel the same way. I've heard more than once from people who were scared of Kirby's work, which is shocking because it's often thought of as harmless kid stuff. But a lot of Kirby's work can be deeply disturbing. It's interesting when you find something that has a seal of approval that's actually very subversive. I think that's what

[Robert] Crumb hit on, drawing in an old-timey Disney-esque style. Kirby can be employed in a similar way.

SPURGEON: Do you think people in Europe and the US take you work in the spirit it's offered or do they bring their own fixations and ideas to it in a way that surprises you? Are you satisfied with how your work is viewed, how people take to it?

SPURGEON: Do you think people in Europe and the US take you work in the spirit it's offered or do they bring their own fixations and ideas to it in a way that surprises you? Are you satisfied with how your work is viewed, how people take to it?

SCIOLI: When people talk to me about it, it sounds like the major things I wanted to accomplish got through. OMIGODTHISISAWESOME is the main reaction I was hoping for and I've gotten a good bit of that from the webcomic. I'm excited to see how the print version will be received. I feel like it'll be a whole new audience discovering it. The small advance print run boded well for things. I've seen a lot of people bury their nose in the book and smell it. At first I thought it was a specifically European reaction, like smelling the cork from a bottle of wine, but I've seen people in the US do it, too. So obviously at the very least the fake nostalgia aspect of the book is working.

More and more I'm treating comics as an activity and a process I engage in. I'm becoming less and less focused on how it will be received. Strangely enough, this is the best received work I've done. What I've learned from that is if you just "do you" people really respond to that. When you second guess and aim to please, you don't give it your all. The danger is the possibility of sliding into irrelevance, but I think it's more likely that it makes you capable of making truly great work. The safety net is no matter how far down the path, no matter how idiosyncratic your work becomes, you can't disappear. As long as there's an internet you can get your work out there. Making boring work is how you make yourself invisible.

I think creators should not give an ounce of worry to what spirit their work is going to be taken in. You have no control over that. You can't even control the format it's read it in. I've had a lot of conversations and in the topic of webcomics in general, there's a lot of resistance from creators about how they want their work appreciated a specific way. Some creators I've talked to are troubled when readers are most attracted to the elements of a story that for the creator were afterthoughts. I'm sure a creator's favorite work is very rarely their most popular work. There's the fan disappointment when you find out your favorite creator isn't fond of your favorite work of theirs.

The instant feedback is one of the things I love about doing webcomics. It is often surprising what people latch on to. It's interesting for me seeing which

American Barbarian original art people buy. Sometimes it makes sense, sometimes it's "out of all the pages, that's the one you want!?" When you create something there are a range of elements in it, many you're not even fully aware of. Some resonate with people for a million different reasons that say a little bit about the work itself, but and a lot about the reader. Comics are incredibly interactive. There are a couple of moments in

American Barbarian where I deliberately played with that. Where I'd ask people, what happened in this scene, and there are a couple of different ways the scene can be read.

I'd found through the process of posting, that the less you spell things out, the more open to interpretation you leave things, the more involved the readers become. I was surprised just how much you can get away with not showing and still have it read the way you want it to.

Everybody has a different version of the story when they read it. I'd hate to ruin somebody's version by talking too much about what it meant to me when I was making it. And it's beside the point. So much of the creative process is mysterious. There's a lot of hammering, polishing and refining, but there's also a lot of digging, and making the best use of the things you dig up. If there's a unifying theme to my work, if my work's about

anything, it's about exploration and that was true of the creative process as well.

Ultimately you can't control how people consume your work. You can't even take for granted that a reader is actually going to "read" your comic. Maybe they'll just quickly flip through a

tumblr or

flickr account of the images. I've been consuming a lot of old comics that way. You just have to hope your work is distinctive enough to survive the translation and hope it's inviting enough that people will want to study it more closely.

*****

*

American Barbarian

*

American Barbarian, Thomas Scioli, AdHouse Books, hardcover, 256 pages, 9781935233176 (ISBN13), $19.95.

*****

* cover image from the AdHouse hardcover of

American Barbarian

* photo of Scioli taken in 2011

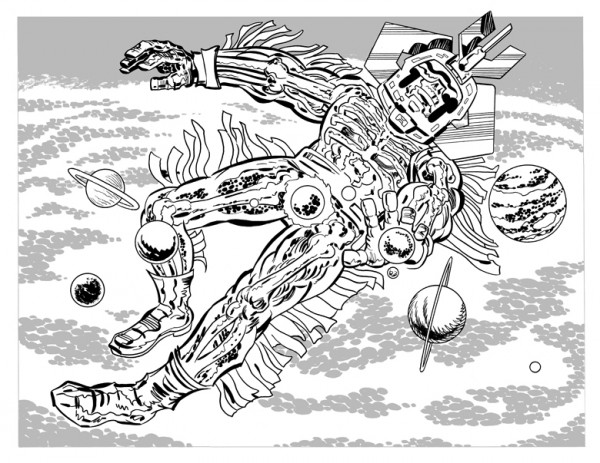

* image from

Gødland

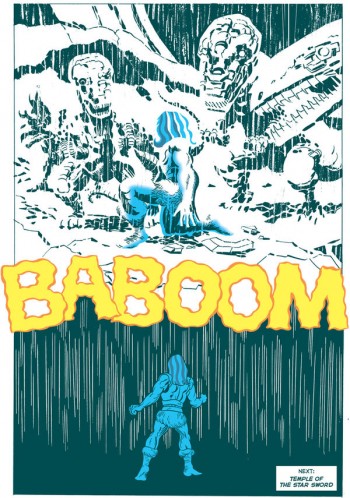

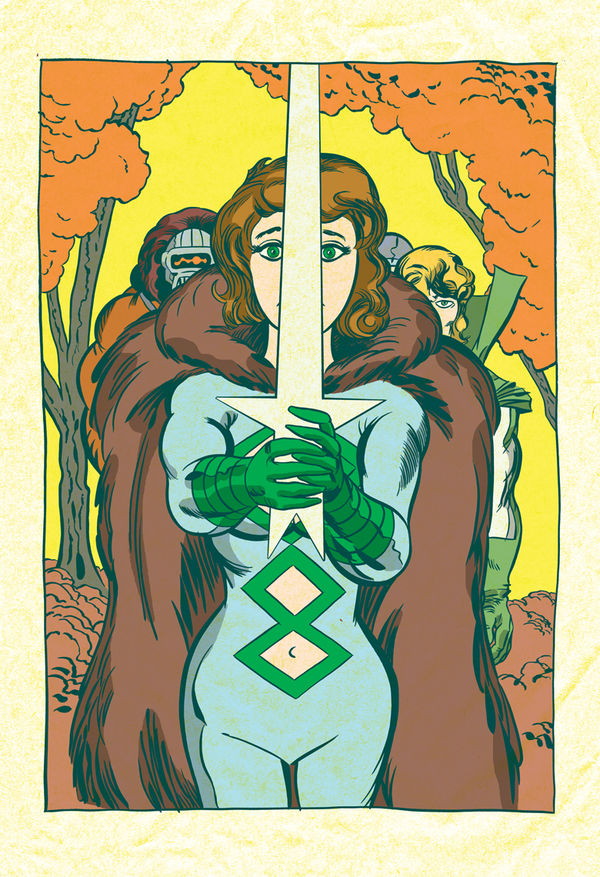

* five images from

American Barbarian, hopefully explained in context

* image from the Angouleme report Scioli did for

TCJ

* image related to

Myth Of 8-Opus

* an image from late in

American Barbarian, just one I liked (below)

*****

*****

*****