Home > CR Interviews

Home > CR Interviews A Short Interview With Austin English

posted January 14, 2006

A Short Interview With Austin English

posted January 14, 2006

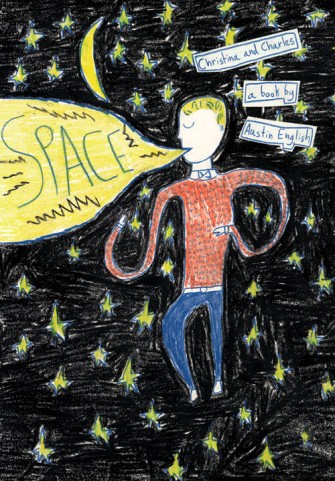

Like many of my professional peers, my first memory of Austin English upon his appearance on the comics scene several years ago is how impossibly young he seemed to be. My impression of English, today still in his early 20s, since that time is of a thoughtful artist pushing at the boundaries of what modern comics will accept in terms of an artistic approach, as well as the rare cartoonist that pursues writing critically about comics as a way to deepen and further his understanding of the art form. Austin's

Christina and Charles graphic novel was released last year by

Sparkplug and is still available from the publisher and the various huge (Internet) or savvy (cream of the crop comic shops) retailers. English also currently writes

the on-line "Dogsbody" column for

The Comics Journal.

TOM SPURGEON: You're young enough I'm going to assume your experience of reading comics as a child was totally different than mine. What led you to start doing a comic at 16 years old?

AUSTIN ENGLISH: I read comics as early as I can remember, especially

Tintin, which my Mom would read to me. In third grade, every single boy in the school I went to was intensely into comics. I made my earliest comics when I was in third grade, and I guess I've always made comics since then. What I always think is funny about my making comics is that I have a very small amount of natural talent for drawing but a

huge amount of enthusiasm for drawing. I started drawing and it was instantly just lower quality then my 8-year-old peers, but for some reason I kept going. I can't explain it. It was just so important to me.

I was easily the strangest drawer in third grade. My drawing was really different then everyone else's. It was very bizarre and crude -- crude for a third grader. I would always be drawing and looking at other kids draw their approach was always different. They'd be holding their pencils in this cool way, and I'd be sort of grabbing onto my drawing tool, making crazy marks. They looked so cool drawing and I looked like a nut. But, all my old classmates don't draw at all anymore -- even the ones I idolized -- while drawing for me has remained incredibly important! So there! Everyone lost interest in comics in fifth grade, but I just got more intensely into them. When I outgrew superhero comics, I just relentlessly searched for comics that still meant something to me. I just read everything, and found stuff like

Eightball and

Chester Brown at a really young age. Pre-teen, I think.

Comics are just inexplicably attractive to me. I love them a ton. I think

Bob Fingerman said that comics saved his life as a teenager, and that's true for me to. I would just change it to "comics and art in general saved my life." I can't express how important it was to have something like comics that I was totally in love with and meant the world to me when I was a teenager. Just to be really interested in making art and drawing -- even though I made crazy weird art that was totally crude, it got me through some tough times. I don't know where I'd be without it. Loving art and loving making art. I can't really think of anything better then that to make you keep going when you're young.

When I was in high school, I was always making comics and drawings, but when I saw mini-comics by

Gabrielle Bell and

Ben Catmull, something really clicked. Their comics where, to me, just as powerful as a really good film or book, but they were published in this way that was totally understandable to a teenager. I couldn't publish a book when I was 14, or direct a film! But I could photocopy some pages at Kinko's. Seeing work that was so good by those two cartoonists in this easily producible form made me want to aspire to making something that good. I still want to make something on par with a Ben Catmull or Gabrielle Bell comic, actually!

SPURGEON: In terms of their being comics towns, can you compare and contrast New York and San Francisco?

SPURGEON: In terms of their being comics towns, can you compare and contrast New York and San Francisco?

ENGLISH: Even though I've lived in both places, I'm not the best person to ask about this. There are amazing artists in both places, and everyone has been very helpful to me. I know that any favor I've needed help with, there has always been someone in either New York or San Francisco to help me with it. I go to this drawing group with other NYC cartoonists once in a while. Very rarely, but I'm always thrilled when I go. I think, even though I don't spend a lot of time with cartoonists from either place, both towns make you feel very encouraged about being a cartoonist. I have a lot of admiration for cartoonists in both cities.

Jesse Reklaw does an amazing job of getting people together to do things in the Bay Area and seems to get people involved in projects even though they have widely different aesthetics. I think that's admirable.

SPURGEON: What interests you about writing on comics? Because that's not a typical impulse for artists.

ENGLISH: My favorite art criticism has always been written by other artists. Besides my hero

Pauline Kael, I would always rather read a filmmaker talking about films or a painter writing about other painters. Present company excluded of course, I feel that it's sad that most of the criticism comics get is from "bloggers' hacking out entries about the latest books that "shipped" this week and their overall "look." Some guys do a good job with this -- i.e. the guys that say nice stuff about me! -- but there is a glut of tepid stuff written by people with none of the passion for comics that cartoonists themselves have, let alone the fact that most of these guys have terrible aesthetic taste. My favorite interviews in the

Journal are

Zak Sally interviewing

John Porcellino, and Pat McKeown interviewing

Dave Cooper. I think those are the interviews where I really learn something as an artist. Tom S interviewing

Evan Dorkin is amazing to me as a reader, but as an artist, that Zak Sally interview with

Kim Deitch in

Comic Art is my holy grail.

That article on comics in The New Yorker really bothered me, especially the bit where Peter Schjeldahl talks about

Krazy Kat. He talks about how what makes

Krazy Kat great is how it's about this complex love triangle. I think he says something like "the eternal triangle." But he doesn't talk about how it's drawn at all! I mean, okay, maybe the love triangle in

Krazy Kat is sort of interesting.it's okay, I guess. But what's really unique and amazing about

Krazy Kat is how it's drawn! It's drawn like nothing else in the world. It's just this amazing thing that's sort of perfect. Perfect drawing that no one could ever duplicate. To write about it in a serious magazine article and not mention the drawing seems so crazy to me. It just misses the point. The drawing in

Krazy Kat is the writing. The drawing is sort of everything.

So, in response, I am starting this new magazine called "Windy Corner." It started out as a place to serialize my next grahic novel. But now I also want to make it a magazine where I interview cartoonists, and commission other cartoonists to write articles about cartooning. I want to make it a magazine that's central mission is to talk about drawing. It will be sort of like the last 15 issues

Peter Bagge's

Hate: 40 new pages of comics by me, and then a bunch of articles. I'm applying for a grant to publish it. Hopefully I'll get it! I think it'll come out someday in some form.

SPURGEON: You do the "Dogsbody" column for The Comics Journal

, which is a real "front lines" position to have in the realm of writing about comics -- you see a lot of first efforts. What have you learned about comics since taking on that position?

ENGLISH: I did mini-comics reviews about five years ago for

Indy magazine, and I had a PO box set up for it and the whole thing. Back then, I remember being really excited by the type of mini-comics I would get. In terms of quality and presentation, they were really beautiful and there was an obvious amount of heartfelt attention being put into them. The first time I saw comics by

Kevin Huizenga,

John Hankiewicz, and

Dave K. was through writing for

Indy and getting these comics, unsolicited, in the mail. It was very exciting to get that work. I feel like the work I see now, with "Dogsbody," is of a much lower quality. Most of the stuff I write about for the column that I love, like

Matthew Thurber's work, it's usually sent directly to me. It's not in the big stack of minis that

The Comics Journal sends you when you start the column.

I just wish people would take more time with their drawings! There's no rush to send this stuff to me. In comics, if you work hard and produce beautiful work, you'll get noticed no matter what. It's not like rock and roll where you can be a genius and never get recognized. If you're a comic's genius, you'll be found. You don't have to send "Dogsbody" your comic right now to get that Pantheon deal. You have to make a really good comic to get that First Second signing bonus! People like

Vanessa Davis just put together great little minis that they spend tons of time on.or spend years becoming a great artist and

then putting out a mini. And then people love them for it! Of course, when I was a teenager, I put out a mini that runs counter to all this that was totally crude. But I like to think it was beautifully crude and totally unique and a breath of fresh air! Plus, even though my early comics were bizarre cultural artifacts, I

did spend a lot of time on them and they were the most important thing to me in the world. I can't imagine that some of the stuff I get sent is as important to these people. I wish it was.

SPURGEON: What led to your interest in doing Monk

? Did you finish that work? How did it change your approach to comics, or how is your approach to comics different now than it was when you started?

ENGLISH:

ENGLISH: I just remember this time when I was 13, and putting on a Thelonious Monk album and being really physically and emotionally moved by it. More moved then I had ever been by any art ever before! I think, as a teenager, it just articulated so many feelings of mine... just this exact aesthetic that I could never really articulate myself. There was something very cool about that record, but also very heartfelt. And I guess I was amazed that you could be cool/heartfelt/strange/weird/smart all at once. Plus, I was, like, a mess emotionally at 13. I mean, who isn't? But I just remember listening to that album over and over again every night and sort of having all the emotions beneath my surface being articulated by it. Like, on the surface at 13, there's depression and whatever. But beneath that there are more interesting feelings. And that Monk album really pointed out all that stuff to me. Because it's music, it articulates emotions that you can't really express any other way. And, so, it showed me that there was this world of emotion beneath my surface that was still

me... but it was like this side of me that I didn't know how to access without that music. Does that make sense? I guess it sounds kind of new-agey or whatever. I hope my friends don't read this part! Um, but, anyway I was very interested in Monk, as a person, because I had had this powerful experience with him. And when I started to want to make comics that I wanted to show people, that's what was on my mind all the time: Monk. By that time I had a bunch of his albums. And I just thought that doing a biography comic would be a great way to learn the structure of really making a comic. Plus, I love him, and I thought my enthusiasm would make for a great comic. I didn't finish, because the biography became too constraining as I got older. But I did make a bootleg mini-comic where I "drew" every note of a Monk song, and included the song on a burned CD. That's my "masterpiece." I'll never top that.

SPURGEON: How did the idea for Christina and Charles

germinate?

ENGLISH: I'm a student at The New School in Manhattan, and I study in the poetry program. It's a program where you take a lot of poetry workshop classes. I was working on this series of poems, which was about this imagined family. I wrote this poem about my brother, and the factual part of the poem is that my brother took me out walking with our dog when I was very young. He did this thing where he said, "If we turn left, there are a bunch of knights waiting for us, but if we turn right, we go into outer space. Okay?" It's just this really vivid memory I have. But my real reaction to my brother doing that was much smaller then how I depict it in the book. I sort of thought "Oh, what a neat idea, for him to say that. How sweet." And the real memory is I just have this vivid memory of looking to the right and seeing a corner store, and then looking to the left and seeing a hill. That's it. But in the book I have the little brother character get really immersed in the fantasy. And then I invent this whole scene with my brother and my mom. That's all invented.

So, I was writing all these poems about a family that were based in really specific memories where I would just change all the reactions to the memory. Invent the emotional content of the memory, but keep the logistical part. It felt really good to do that, for some reason. Sort of like talking to someone and making up the details of your life to make them seem more exciting! And the poems would sort of come out fully formed. I wrote those poems so quick. The kids in my workshop classes really liked them. They were very helpful in me having the guts to show them outside of class.

At the same time, I was writing another set of poems about a teenage girl. That had a sort of different strategy to it. I wanted to write about two things: my idea of teenage girls, and how I think they're cool and stuff. How there's this specific cool thing about teenage girls. Y'know? They are inherently interesting. But I also wanted to write in a teenage girl voice, because I still have very teenage -- and pre-teen -- type emotions. I am constantly taking everything as a larger then life event and just endlessly analyzing people's gestures and expressions in regards to me. I do this awful thing where when people talk to me, I can barely focus on what they're saying sometimes. I'm just watching their face and thinking, "what does that mean? The way their moving their lips as they talk. Just what are they getting at?!?" It's really silly but also kind of this big force in my life. I hate how concerned I am with analyzing people and interactions and their gestures towards me. It's really exhausting, but at the same time, it makes for kind of unique art (I hope). It's a sort of a unhealthy viewpoint that I'm working on to sort of, y'know,

change. Still, it's

my viewpoint. But I felt like it would be less absurd if a 15-year-old girl were interacting with people in this way, and not a dorky, older boy.

I do have a certain degree of affection for the way I hyper-analyze people and things. It probably hurts me, in the long run, but I decided to sort of glorify it with Christina. That's what my favorite books do. My favorite books, like Emile Zola or Stendal, are sort of all about that: picking an emotion that's problematic but also sort of being in sympathy with it.

So, those two things, they eventually became

Christina and Charles. When Dylan [Williams] approached me about doing a book, those where the things I was working on changing into comics. And Dylan approaching me to do the book was such a big shaping force on my work. I really made a sort of breakthrough with my art, since it was such a huge pat on the back -- and such a huge chance to take on someone without a big fan following or anything. I love everything Sparkplug publishes and was thrilled to do a book with them and it gave me so much confidence to do stuff that I don't think I would have had the guts to do otherwise.

SPURGEON: How much of the work is autobiographical? How much of it is a book that you can still do because you're reasonably close to your characters' ages?

ENGLISH: It's only autobiographical in the sense that the situations are based in fact. For instance, when I was in high school, we just had this hotplate at my moms. We didn't have a stove. But when my friends come over and were kind of weirded out by that, I felt kind of punk rock about it. I was more like "yeah, man. We just have a hotplate! Deal with it!" But, in the book, I make Christina all bummed out about it. But that makes sense for her. She doesn't really get mad about stuff. Just seething, y'know? But that's me, too. I just seethe! But in different situations. I wouldn't seethe about the hotplate thing. For some reason I didn't put in any scenes where the situation (i.e. a hotplate) and the emotional reaction (i.e. seething) sink up. It just felt a little too whiny to do that. I'm more interested in making characters then I am in talking about myself. The next book I do is all about me as a kid, but it's all made up in the same way, sort of. It's like the kid in my next book is a character too, even though all his experience are ones I had. But he has different reactions to everything.

The stuff about my brother is really just about the

idea of my two brothers. They're just these very amazing figures to me that I have so much affection for but whom I also feel totally removed from. Both my brothers are 18 and 19 years older then me, respectively, so I get to have a huge amount of awe and respect for them, but also not really know them at all -- on an intimate basis at least. I never lived with them. I spend a lot of time with one of my brothers, but not the amount of time you'd spend if you were one year apart, I guess. Anyway, I have a feeling for my brothers. They were this force in my life that I think about, but I don't know many details about them. So I made up a bunch of details based around this feeling of awe.

There's this amazing picture of them in the mid-80s with just this flawless punk rock look. But the book isn't about them, because their teenage years are a hundred times more complicated then that punk rock photo. So, the book is really about my reaction to that photo, I guess. My feeling for the idea of them.

SPURGEON: I have to ask about your art. How would you ideally like people to approach your art? Specific to Christina and Charles

, how should the reader look at your art as simply depicting action, and how much should they look at it as an expression of the characters who are speaking, if at all?

ENGLISH:

ENGLISH: The drawing I'm doing now is so much different than

Christina and Charles. The characters barely move in

Christina and Charles. They're very static. My next book the characters are moving like crazy! There's all this movement. And I feel like that's much closer to "true" comics.

The drawing in

Christina and Charles is my attempt to really get across the mood and tone I wanted for those poems. I think making the poems into a comic gives you so much control over the way the poem reads. The drawings really color the poem. When I was writing the poems, I already knew I was going to make it into a comic, so I was including images and scenes in it that I thought I could express in a clearer way as comics.

The poems, by themselves, read very dryly and very somber. But I wrote them hoping they'd be funny. Not gag-funny, but funny in the way that a charming high school kid is funny. I drew the thing in my weird style to get at that. I hope people feel like it's funny. But heartfelt-funny. The New School let me do a little reading from the book a few months ago and I tried to make it as funny as possible, but it was hard to do without the drawings. Plus, I don't get any physical pleasure from writing, but drawing is my favorite thing to do in the whole world. So, whenever I write something that I like, I always want to turn it into a comic or make it into an excuse for drawing.

But my next book will be more of a true comic, in the sense that it didn't exist as poetry first, and the characters are moving around.

SPURGEON: Your characters don't seem to be able to make easy connections, and they both seem to get in their own way, I would say through benign self-absorption. Do you agree that both the characters lack human connection, and is this something you were trying to explore about human nature?

ENGLISH:

ENGLISH: I think they do have human interaction Tom! But they sort of over-analyze their human interaction. I think it's maybe that they're

too absorbed in the people they interact with. I think they also notice a lot of stuff about other people. But, I think they also make up a lot of stuff about people that becomes true to them but maybe isn't so true. Again, I'm sort of in sympathy with this and of not in sympathy with it. I like paying close attention to people and inventing melodrama to go along with their little gestures, but I'm a little afraid of over-doing it or believing in the melodrama that I make up. I totally believe in that stuff.

I do think the little brother character notices a lot of stuff, and he notices lousy stuff happening to people he cares about, but he just notices it along with everything else. He doesn't go "oh, how awful." It's more "I noticed this and I noticed this" and everything has an equal emotional value.

I feel funny answering this question, but it's interesting! This is the first time I've really thought about the book like this.

SPURGEON: Are you going to continue to do comics? What kind? And will you continue to write about them?

ENGLISH: Yes, of course I am going to keep doing comics! I am going to make comics for the rest of my life! I'm so glad that I'm so young and that I have so much time to work on getting better at art. I feel like

Christina and Charles is my first real thing -- the first comic I did where I felt like I was in some kind of control of what I was doing and that things were coming out in an interesting satisfying way. I'm so excited -- really, genuinely excited -- to keep building on what I'm doing, until I'm an old man. Comics are so great in that way, when you look at guys like Kim Deitch who are doing the best stuff in the world right now after they turn 60. I don't think other arts really have that arc. Certainly not music, and usually not painting or literature. But comics.it seems like if you keep caring, you can get better and better. Writing and drawing

Christina and Charles was such a pleasure. Coming home from work to draw that thing was such a thrill, and I've really set up my life so that I can draw a little bit (at least two hours a day) almost every day. I wish I could draw more then that. When I have time off from school, I do a huge amount of work. I sort of envision working shit jobs for the next 10 years or whatever, but the prospect of drawing after work makes lousy, shit jobs seem totally do-able. I guess that's a really young-kid-mouthing-off thing to say, but I believe it!

I'm 100 pages into my next book, which is a catalog of all my childhood memories. I think that will be done in a year or two. I'm also doing two other books simultaneously, one of which will be this detailed novel type thing. I'm thinking of it as a Henry James novel as illustrated by

Milt Gross! I'm pretty excited about it.

I feel like I have a limitless amount of things that I want to draw, and I have a ton of energy to draw them. Maybe this

also makes me sound like some young kid, mouthing off, but oh well! It's the truth! I sort of see comics as a lifelong project. Something you work at your entire life and get better at.

I was looking at Milt Gross drawings earlier today, and they're just so great. Looking at him has changed the way I draw. He's just as good as any other artist in any medium. Stendal, Klee, Gross! I love him and I feel lucky to get to do stuff like that -- to draw stuff like that and have people be interested in it. Some people feel funny about calling themselves an artist or whatever, but I think it's the greatest thing in the world and I'm in it for the long haul.