Home > CR Interviews

Home > CR Interviews CR Sunday Interview: Adrian Tomine

posted September 30, 2012

CR Sunday Interview: Adrian Tomine

posted September 30, 2012

*****

Adrian Tomine occupies a unique place in the art-comics landscape, as a cartoonist that was both the last of an era of solo-title developed talents and as one of the main beneficiaries of the context created by the 15 years of comics-makers that preceded his rise. His latest,

New York Drawings is a surprisingly hefty volume of work from what he considers a separate artistic endeavor: commercial illustration, dominated by a longstanding, recurring gig with

The New Yorker. Many of the virtues of Tomine's comics are on display in

New York Drawings, and not just those few pages devoted to comics: strong composition, an attractive line, clarity of concept. That one of the all-time "one cartoonist, one comic" cartoonists has in recent memory done this much work not that comic book and has, in fact, released three very different projects (this new art book,

the latest issue of his comic title Optic Nerve, the light-hearted gift book

Scenes From An Impending Marriage) in recent memory seem to me developments worth noting in conversation. Besides, I sort of just like talking to Adrian, so any excuse. He's on tour right now, so I am extremely happy he took the time to chat. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: When

TOM SPURGEON: When New York Drawings

was first announced, I was like, "Okay, I know what that's going to look like; I basically know what he's been up to." And then when I got the book it was like three times as thick as I thought it would be. You've done a lot more of this kind of work than I thought you had. Do you think people are going to be surprised by how much illustration you've done?

ADRIAN TOMINE: I was surprised. I had to do a few test runs of counting out the illustrations and figuring out possible page layouts before we decided to go through with it. I had the idea for the book before I really knew if there was enough material. Yeah, I was actually surprised. To me it seems like I just started working for

The New Yorker. [laughs] I guess it's one of those things that makes you feel kind of old when you realize it's been going on for quite a while. Also, I have to give credit to Jonathan Bennett, who designed the book. He found a way to make it seem substantial but not too dense and busy. He gave it this kind of airy elegance that I was glad to have in the book.

SPURGEON: So that was Jonathan. Because I wondered about that as well. The design is effective in exactly the way you describe.

TOMINE: This is the first time I didn't design a book myself. Every book I've ever done with Drawn And Quarterly I've designed from top to bottom. With this one, with a kind of retrospective thing like this, I figured it was going to be helpful to have a little more objective point of view in terms of how to present it. Jon was the designer, but he was also, in the process of putting it together, literally the only sounding board I had. Drawn And Quarterly is very hands-off, so it was more just like in the process of putting it together I was sending a million e-mails back and forth with Jonathan saying, "Do you think this should be in the book?" or "Should we cut this one out?" or "What do you think about this or that?" He was really helpful in more ways than just the concrete page layouts.

SPURGEON: You said you went through the material; do you have all of this stuff? Do you keep your material? Are you a meticulous archiver of your own work?

TOMINE: When I started doing illustration work there was never a glimmer of any kind of thought in my mind of there being a book of the illustration work at any point. It was more just like trying to make a buck. I'd actually go to the newsstand and seek out the magazine that had my illustrations in it, buy it and clip it out. So I had these binders of every illustration I've ever done. Sometimes it's a tattered tear sheet I ripped out of the magazine or something. I kind of thought that would be the extent of the archiving. It would just be for my own ego. [laughter]

SPURGEON: I talked to a very prominent alternative cartoonist about his illustration work a couple of years ago. It was an innocuous question where I kind of assumed that it was a good gig. He answered back pretty strongly that as much as he appreciated that work it wasn't his comics, and he didn't like the time away from doing his comics. How are you oriented towards the illustration work? I don't want to get you in trouble with an editor, but that cartoonist's response fascinated me.

TOMINE: I've been there. I went through many, many years of being on that exact same page. Especially when there was such a great disparity between how much money you could make spending a day doing illustration versus a day doing comics work. It used to kind of drive me crazy. I think that... well, a lot of things have changed. Comics have become a more legitimate job in certain ways. On a personal level I've become a father and that's had an impact on my relationship to illustration work for sure.

SPURGEON: How do you mean?

TOMINE: I think every new parent goes through that period. It doesn't quite hit you until you're holding that kid in your hands that, "Oh my God, I'm responsible for this." [laughter] "I've got to pay these bills." No matter how much you think about it in advance. I used to be in this very, very luxurious position of being almost kind of put out when I had to do an illustration for something. You know? Now especially when I'm watching some of the choices other of our young-parents friends have to make in order to pay the bills, I'm a lot more appreciative of the illustration work that comes my way.

Also, even before having a kid I consciously made this choice to really think of it as two different jobs, to think of myself as sometimes a cartoonist and sometimes an illustrator, and bring totally different levels of expectation to those two jobs. I think when I started doing illustration work, I was very spoiled by the

carte blanche that Drawn And Quarterly had given me. I felt I was entitled to do whatever I wanted, whenever I wanted. [laughter] And suddenly there's an art director making changes to your work, and criticizing it, giving you very tight deadlines. It was kind of a shock to me at first. It was probably more indicative of how easy I had it at Drawn And Quarterly than anything else. I separated the two, and decided there was one area of my creative life where I have complete and utter freedom and one where I collaborate with people. That's how I really approach illustration work now.

New Yorker illustrations I think of as collaborations between

Chris Curry or

Francoise Mouly or some of the other art directors I've worked with.

SPURGEON: A natural question about your having done this much illustration work is whether or not you think it's had any effect on your comics-making, your cartooning. So much of the work is for the New Yorker

, and they do have a tendency to favorite narratives within a single image, the kind of thing that one might think would be very transferable to comics. Is your cartooning different for having had this second job?

TOMINE: In two ways. From a purely artistic point of view and then from a "my position in the world" point of view, too. For me, it's been helpful -- again, like I said -- to separate illustration from cartooning. That clarifies for me how to draw when I'm working on my comics versus how I'm drawing for illustration work. I feel like there was a time early on where I was trying to prove myself in some way with every panel that I drew to make it as dense with detail and everything. Especially as I've gotten older and studied other cartoonists' work, both from the past and the present, it's really encouraged me to be more economical in my cartooning, to sort of let the pictures tell the story. Not to try and knock you out of your seat with how amazing the three-point perspective is, or something like that.

I feel like the illustration work is a good place to funnel a lot of those tendencies. Let me really get the detail work of this subway car exactly right, down to the bolts in the seat. That kind of stuff. Or let me really, really fret for like a week about the balance of colors in a single image. I feel like I do have that compulsion to make these sorts of precise... I'm not sure what the word is, but there's some pleasure I get from that kind of work, which can be a detriment when you're trying to crank out a comic.

SPURGEON: You included some of the sketches you did around New York when you first got to the city. You say, and it makes a certain amount of sense, that one of the reasons you were doing that was to explore the city, to see new things in a different way. Was that useful in getting accustomed to New York and your new life there? Was that a valuable experience?

SPURGEON: You included some of the sketches you did around New York when you first got to the city. You say, and it makes a certain amount of sense, that one of the reasons you were doing that was to explore the city, to see new things in a different way. Was that useful in getting accustomed to New York and your new life there? Was that a valuable experience?

TOMINE: I think the fact that it prepared me for doing more specific drawings of New York for

The New Yorker and

The New York Times was kind of... it was great, but it was almost an ancillary benefit to some sort of psychological effect that it had on me. I don't want to overdramatize it, but I did live on the west coast for my entire life, and Berkeley for almost 15 years or something like that. So to move anywhere and in particular to move to New York was a pretty dramatic change for me. I had a very predictable and comfortable zone that I lived in in Berkeley, literally and figuratively. Then I threw myself into this whole life here where I basically knew one person, which was my girlfriend. Beyond that I felt pretty much on my own. It was some sort of... I don't know what it was... it was some sort of

therapeutic process for me. I think it's going to be a long time before I have a kind of knowledge and understanding drawing New York that I had with California. I felt like I put myself through a crash course.

SPURGEON: It seems like -- and this could be a projection on my part -- that the later stuff in the book comes from the eyes of a New Yorker more than maybe some of that stuff earlier on. There's an ease to what you're seeing, the scenarios depicted seem maybe more settled and specific.

TOMINE: That's true. The earliest stuff in the book, from when I first started working with

The New Yorker, was from when I was still in California. So there's a good chunk of that early section where I was making stuff up or working from photo reference or kind of thinking of New York based on [laughs] sad to say, comic books and movies that I'd grown up reading. It's a good thing I didn't accidentally draw the

Daily Bugle lying around. [laughter] I wouldn't say there's any kind of authority that develops; it's more easy access to the real thing. I can get on the subway and do my sketches, go out and see what a Brooklyn brownstone really looks like.

SPURGEON: I have a question about the cinema stuff you were doing early on. It looks like some of them were difficult for you to do. Are there one or two that you think you nailed it, that you're particularly happy with? And what about them makes you happy with them? What works for you when you do that particular kind of assignment well?

TOMINE: That's a good question. They really had me working in that one area for quite a while, and the whole time there was a little part of me thinking, "You know, you might be better off if you got one of the caricaturists, the more cartoony people to do this, to be able to nail the likenesses a little better." There was a lot of back and forth for us about "It doesn't look like this celebrity" or whatever.

Let me look through the book right now. It's difficult to say, "I nailed that."

At this point, the only way I can look at them is in terms of how it looks on the page. I can't even tell you how well I based the likenesses, it's almost abstract. I can say the composition looks nice, or the colors look nice. [slight pause] There's this one I did for a movie that I don't think anybody remembers called

The Mexican with

James Gandolfini and

Julia Roberts. That was a tough one. Julia Roberts I didn't get at all. She was really hard to draw without it being a slightly mean-spirited caricature. They said, "No, make her look beautiful. That's why we want her in the image, because she's a pretty movie star." So that was hard. But I look at it and I'm like, "Oh, I like those colors. The composition is nice."

Most of those movie things I was working from very limited reference material. Most of those were done pretty much before the Internet had entered into my life in an everyday capacity. I didn't get to see the movies. A lot of the time they would send me a Fed Ex package with a few stills from the movie. On some of them the deadline was so tight they even faxed over [laughs] photos, and I had to decipher the image on this crinkly fax paper. [Spurgeon laughs] I think if I were working that assignment now it would be a little easier, because you could type in "James Gandolfini" and find every type of image and photo of his face. The hardest ones of those when they were having me draw those were the good-looking but sort of hard to distinguish celebrities. The last one that I did was supposed to be the actor

Ryan Phillippe, who I just couldn't make look both handsome and recognizable as him. It was like I could do a caricature, but it won't look good, or I could draw a handsome blond-haired, blue-eyed guy, but it won't be... it was difficult. They eventually came to their senses and moved me on to other kinds of assignments. [laughs]

SPURGEON: I want to ask you a couple of broader questions about your career. You've been working with Drawn And Quarterly for a long time now. They're a very different publisher in some ways than the publisher with which you started. I wondered how that relationship has changed over the years. How are they a different publisher now for you? You intimated that the basic relationship is the same, that you receive the same type of support you've always received, but I wondered if there are ways that might be noticeably different.

SPURGEON: I want to ask you a couple of broader questions about your career. You've been working with Drawn And Quarterly for a long time now. They're a very different publisher in some ways than the publisher with which you started. I wondered how that relationship has changed over the years. How are they a different publisher now for you? You intimated that the basic relationship is the same, that you receive the same type of support you've always received, but I wondered if there are ways that might be noticeably different.

TOMINE: It's hard for me to say, because I think

Chris [Oliveros] in particular might feel some sort of obligation to keep things consistent with the older cartoonists that he signed up. I've heard from other cartoonists that started working for Drawn And Quarterly subsequently that there are some differences, the experiences they've had, so I don't know. I think someone like

Sammy Harkham might have a different take on it than I do.

I feel like Chris has -- I don't know how explicit he's been about this, but he's always gone out of his way to make sure there's a real consistency to our working relationship even as the market has completely changed and even as the personnel in the Drawn And Quarterly office has changed. For someone like me, that's among the greatest gifts that a publisher can give to me, this feeling of stability, to basically eradicate the concerns about business and whether or not the book will look good and all of these things that could really take up a lot my thought process.

SPURGEON: Is it that you'd just rather not think about those things?

TOMINE: Yeah. Yeah. I'd rather not think about it. I sometimes take for granted how little I worry about how the final product is going to come out in terms of printing and all of that. That's a relief. I know of people who have worked for other publishers where they're deciding do they want to pay their own airfare to go do a presscheck because they can't trust if it will come out looking right. They're arguing over slightly better paper stock -- all of this stuff that doesn't enter into the conversation with Drawn And Quarterly.

I think it's been great for the company that they've made some really smart moves and kind of managed to evolve and grow in sync with the industry and its place within North American culture. There was definitely a moment where Drawn And Quarterly could have been stuck in their niche and all of the cartoonists could have started jumping ship and going to mainstream book publishers. They stepped up their game -- at least from my point of view -- and gave me no reason to look elsewhere for a publisher.

SPURGEON: You mentioned market realities. The market

SPURGEON: You mentioned market realities. The market has

fundamentally changed. Your last three releases, if I'm remembering correctly, are the stand-alone book based on your wedding comic, this book which is an art book and the latest issue of your comic. [Tomine laughs] That's three very different things, and when I think of my long-term relationship with you as a reader it was developed very consistently through the comics. Is that something you're growing accustomed to, that you'll be publishing in a variety of formats now, that there's not going to be this consistent comic-book relationship at the absolute forefront anymore? How have you oriented yourself to that change?

TOMINE: I think I'm really lucky that there's a market and that it's feasible for me to put out things that are different than an issue of a comic book. I definitely have to give a lot of credit to

Peggy [Burns] and Julia [Pohl-Miranda] at Drawn And Quarterly for tackling each project as its own thing. We're going to do this weird wedding thing as a gift book, so instead of sending out so many copies to the comics press, try to get it into

Kate's Paperie or something. [laughter]

SPURGEON: That makes perfect sense.

TOMINE: In the case of this book, it'll probably sell more in art-book kinds of stores, New York museum gift shops, more than a comic book store in the midwest. That's been lucky for me. For me that's been a conscious choice to put out a series of different kinds of books. The series you mentioned, when you described them I thought, "Yeah, those three are pretty different." When i finished

Shortcomings I sort of sat down for the first time in a long time and thought about what I was doing next and how to proceed with it. The thing that kept coming to mind was that the worst thing I could do would be repetitious in some way. I'm not saying that I broke new ground or did something shocking. I just thought that no matter how good it was, if I did another book like

Shortcomings that hits the same kinds of emotional notes, it's going to get trashed. People are going to write me off and say, "That's it." I recognize that the wedding book is fluffy and insubstantial, but I really considered it. Better to do something fluffy and insubstantial and sort of different than maybe a little bit more serious and ambitious but in the exact way of

Shortcomings.

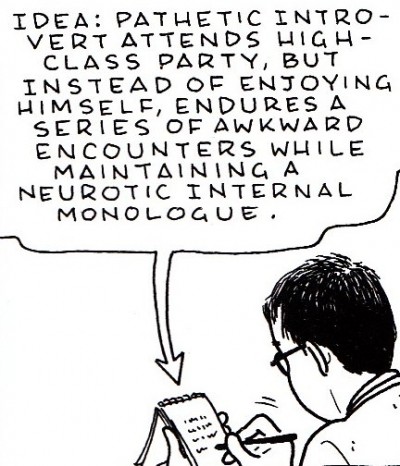

SPURGEON: The comic you include at the front of New York Drawings

has a verve to it; it's very light on its feet.

TOMINE: Yeah.

SPURGEON: You know, when my friends and I talk about your work --

SPURGEON: You know, when my friends and I talk about your work --

TOMINE: That common occurrence! [laughs]

SPURGEON: -- one thing that usually gets mentioned with you is that you're funny. That personally, you're a funny guy. That doesn't always come out in your work. And yet the comic in New York Drawings

is highly amusing. Is that anything you want to pursue? Because it seems like you would have a facility for that.

TOMINE: I am trying to be more open to that.

SPURGEON: Not that your comics have been grim going over the years, or anything. [laughs]

TOMINE: You have to remember the tenor of things when I was starting out, which was so different. I almost had a chip on my shoulder to differentiate myself and my work from what people thought stereotypically comics were: either superhero stuff or comedy for children. I got stuck in a rut trying to present myself as "serious" and "literary" -- in quote marks -- which is obviously very limiting and not a lot of fun. [Spurgeon laughs] I think there's a feeling of greater freedom now. I give a lot of credit to my wife, too, in this regard. When we were first spending time together, she said something similar to how you phrased that question. "You love comedy movies and shows and you're always joking around, and then you sit down and do these grim-faced, tear-jerking stories." She's a very smart and well-read person, so the fact she was encouraging a move in a more funny direction was eye-opening to me.

SPURGEON: I saw one of your panels at the recent SPX, I think it was called "Life After Alternative Comics." You appeared on it with Dan Clowes and Jaime and Gilbert Hernandez. It was interesting how they positioned you.

TOMINE: Yes!

SPURGEON: They positioned you as this kind of... kind of development in that form [Tomine laughs] in that your work wasn't contextualized the same as earlier work from the Bros or from Dan but was still kind of bouncing off of the same ideas. How do you see yourself in terms of those peers of yours? You're younger than a lot of those guys. Yet I think there's definitely a way of looking at alternative comics where you kind of come in at the tail end of a certain unique mode of expression. Do you see yourself in a continuity with the 1980s alt-comic pantheon?

TOMINE: I felt uncomfortable being on that panel. The three guys who were on the front lines and then the guy that got to coast in on their coattails, or something. [Spurgeon laughs] I think it would have been more complete to have a few guys from my own age group.

SPURGEON: Who would you consider your peer group if not those guys?

TOMINE: It's hard to say, because those guys are among my closest friends. They've been really welcoming to me for a long time. In that regard, if I'm outraged by something I read on

The Comics Reporter, I'm going to fire off an e-mail to one of those guys, [as opposed to] maybe some of the people a little closer to my age range. Yeah, I felt a little uncomfortable up there. I feel like I came along... the timing was just perfect for my age and my interests, for when I tried to thrust my work upon the world and everything, that I really got to benefit with each step of acceptance of comics in America. As an art form. I'm not sure I would have had the determination and humility that was required of people like the Hernandez Brothers and even Dan to a degree, to have your work relegated to the porn section of the comics stores, and have these endless explanations to normal adults in terms of what you do for a living. [laughs] All these things they made the world safe for.

SPURGEON: You could make a very odd diagram out of people the Hernandez Brothers were compared to over the years.

TOMINE: That they were compared to?

SPURGEON: Yeah. Like "Love & Rockets, blank and blank." When they would mention great comics. You could see how the context has changed around the Hernandez Brothers just based on who they might get listed with. For a long while their work was compared to comics that really had nothing to do with what they were up to.

TOMINE: Like

Flaming Carrot and

The Dark Knight. [laughs]

SPURGEON: That must have been bizarre.

TOMINE: Yeah. Back then if you weren't doing superheroes, you were all kind of in the same boat together.

SPURGEON: So one thing those guys, and Dan, and others did for a cartoonist like you was help create a context for people to grasp onto your work more directly.

TOMINE: Not just me, I think there's a lot of us working now that would not have such an easy go of it if not for those guys.

SPURGEON: You've been around a while yourself now, of course. You know, you mentioned earlier that you engage with current comics as well as past work. Can you give an example of one or two newer folks that you've read that you became interested in? I'm interested in how you read.

SPURGEON: You've been around a while yourself now, of course. You know, you mentioned earlier that you engage with current comics as well as past work. Can you give an example of one or two newer folks that you've read that you became interested in? I'm interested in how you read.

TOMINE: Sure. I try to check out everything that comes out. There's still this part of me that wants to just read comics as much as possible. I even buy stuff that doesn't initially appeal to me to try and understand it.

SPURGEON: Is there anything you've been taken with recently? If I remember right, you had a letter in Ethan Rilly's new issue of Pope Hats

.

TOMINE: Yeah. When you look at what's happening in comics now, especially amongst the younger generation [laughter], I'm a little bit of a fuddy-duddy, I'm a little bit conservative with my tastes. I buy most of the stuff that

PictureBox puts out, but I can't say that I completely get my head around everything there.

Pope Hats was kind of shocking to me, and I think the thing I like about it is that he's picking up almost where the Hernandez Brothers left off. He doesn't seem at all influenced by the more experimental and more psychedelic stuff that's come along more recently.

I'll mention

Jonathan Bennett again, even though he hasn't been doing a ton of cartooning work. The stuff that he did in

MOME and some other anthologies had quite an impact on me as a cartoonist. In my next book of actual comics people might be able to detect that a bit.

SPURGEON: What quality of his did you react to?

TOMINE: His work came to me at a perfect time when I was really... I think I got to know his work and became friends with him right at the time I was particularly haunted by [laughs] something that I read about

Chris Ware's work. I can't remember who wrote it. It might have been in

Dan Raeburn's book about Chris Ware. It was talking about

one of the ACME covers, and it had this very stylilzed drawing of a cat with tears coming out of its eyes. The thing that I read was talking about how beautiful and what an impact that image could have, whereas if it was drawn realistically, like a furry, realistic cat with actual glistening tears dripping down its face, how repulsive and how alienating that would be. I remember reading that and going, "Oh my God, I'm drawing glistening, furry cat faces." [laughter]

With that on my mind, and having just finished up

Shortcomings and then seeing the really unpretentious and clean cartooning Jonatahan was doing in

MOME... I don't know exactly, but I imagine it owes a certain debt to

John Stanley and some of those old cartoonists. But for me it was useful to be reminded of the beauty of minimalism and simplicity and symbolic imagery rather than detailed representational imagery. Also, I feel the mode he was working in was something that meant a lot to me when I was becoming interested in alternative comics. It's not as prevelant anymore. What's the word...? Not "mundane," but the quotidian details of life. That was the kind of stuff that really opened my mind up when I was getting into comics. So some of Jonathan's stuff reminded me of the early

Harvey Pekar/

Robert Crumb stuff that I enjoyed, which was far less sensationalistic: picking up a loaf of bread, or being unable to get out of bed one morning.

I felt that a little bit, too, when I was reading

Vanessa Davis' work when I first saw it -- that slightly voyeuristic quality of getting a peek into somebody's private life and also seeing the humor and the drama in the minutiae of life. Looking at her work was also affecting to me in that it was kind of... not carefree, but alive and unfussy. I don't think that influence is apparent in my work or anything. I've got no shortage of influences when it comes to being precise and fastidious and all of that in terms of my comics work. So it's helpful every once in a while to see someone that's going straight in with the ink and watercolor instead of penciling it all out.

*****

*

Adrian Tomine

*

New York Drawings, Adrian Tomine, Drawn And Quarterly, hardcover, 176 pages, 9781770460874, October 2012, $29.95.

*

Adrian Tomine on tour in support of New York Drawings

*****

* Tomine at the 2011 Brooklyn Comics And Graphics Festival

* cover to the new work

* illustration for

The Mexican

* a panel progression from Tomine's comics work

* strip from

Scenes

* one of Tomine's sketches from around New York when he initially got there

* panel from the comic included at the front of

New York Drawings

* a well-liked, well-traveled illustration of Tomine's

* one of Tomine's most-lauded illustrations, or at least one that I've seen mentioned a bunch (below)

*****

*****

*****