Home > CR Interviews

Home > CR Interviews CR Sunday Interview: Howard Cruse

posted November 18, 2012

CR Sunday Interview: Howard Cruse

posted November 18, 2012

*****

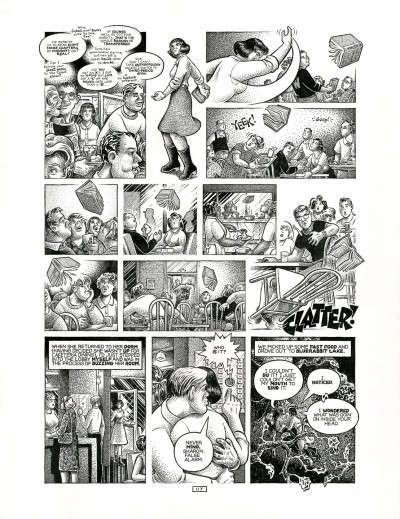

The latest book from underground comix legend

Howard Cruse is

The Other Sides Of Howard Cruse, a hardcover volume from BOOM! collecting material that doesn't touch on gay culture or related political issues. Cruse may be best known to modern audiences for his

Stuck Rubber Baby, one of the mid-1990s major book releases that presaged the modern bookshelf-driven comics market. The latest book throws a spotlight on a number of the cartoonist's 1970s and 1980s works, including a lengthy run of the

Barefootz cartoons through which he made his initial reputation. I enjoyed the new book, particularly how quickly and naturally Cruse took to essay and autobiographical forms that were in no way set in stone by the time he employed them. I am grateful for his time. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: I was wondering how this particular book came together. Was the phrasing, "The Other Sides," in the title, was that yours?

HOWARD CRUSE: There was a lot of back and forth about the title, and that was sort of the one that was voted in. [laughs] It was one that I suggested. The whole point of the book is that everyone is used to all the gay stuff. This is the other sides of my interests. I made sure it was plural, you know? The idea is that there is a bunch of different sides. Parts of the book are different from each other as well.

I've never worked with

BOOM! before. This all happened because

Denis Kitchen was working on a project with them, and they got to talking about my work and it turned out the editor at BOOM! liked my stuff. They came up with the idea of doing a collection of my non-gay stuff. Denis called me and asked if I was up for it, and I said, "Sure."

SPURGEON: Do you feel like those sides of your career have been neglected, that you haven't received your due in terms of certain kinds of comics? Or was that more of a convenient organizing principle? I'm trying to gauge how angry you are in that title, Howard. [laughs] Is this "pay attention to this stuff!"? Or is this more "here it is"?

CRUSE: [laughs] I don't see it as an angry title, I see it as more of a "By the way, in case you've totally begun pigeonholing me... [laughs] I'm more than the gay cartoonist." I think it's useful. It's not that I feel someone's consciously neglecting me or anything, it's just that for obvious reasons the more unusual role that I've played in the comics field is bringing myself -- and helping to usher other gay and lesbian cartoonists -- into visibility. It's entirely understandable that's something that would catch people's eyes. And, of course, the gay material, I have a special passion for it, because you're dealing with the very fundamental aspects of my individual personality.

On the other hand,

Stuck Rubber Baby gave me a chance to deal with issues of racism, which I had not dealt with a lot even though I come from Birmingham during the Civil Rights era. It was too big a topic. I needed a big canvas to do something that would be worthwhile, that would include that theme. Similarly, there's a bunch of things that I feel passionate about or want to satirize or simply that I like, like parodying

Little Lulu. These are things that have nothing to do with being gay. During my years in underground comix, I had a fairly open door at Kitchen Sink to go this way and that on different topics. So all of this stuff, a great deal of this stuff, has been out of print since the earlier collection

Dancin' Nekkid With The Angels. That went out of print in the mid-'90s. You have practically a generation of people that have never seen all the stuff that I was doing for underground comic books. And also there's the material that I've published since

Dancin' Nekkid, which was published in 1987. They were all things that I was very fond of, but they were kind of scattered around in odd places like

Art Forum International or the abortion rights book

Choices -- things that people wouldn't run into in the normal course of things. So I was very happy to have a chance to pull all of this stuff together. There's a lot of it I'm very proud of.

SPURGEON: You mentioned the strong relationship you had with Denis, the fact that it was a multiple-pronged platform, that you could aim your pen at a lot of different things with the publishing opportunities he gave you. Even given the wide array of material in this new book, do you feel that you've covered all of those things you've wanted to cover? Are there comics, maybe even a whole kind of comics, still in you that you never got to? I know that when I've talked to cartoonists, some feel like they have to make some pretty dramatic choices just in terms of being able to get to certain works in the limited amount of time we all have to do art in our lifetimes. These can be tough choices.

CRUSE: Right.

SPURGEON: Are you satisfied with the breadth of your career?

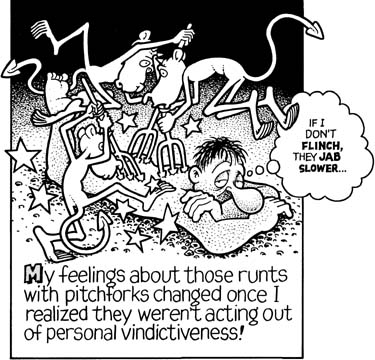

CRUSE: Well, I'm not satisfied with the fact that at my age, at this point in life, you're more aware that life is not infinite. You do have to make choices about what you're going to devote your energies to. It's not just a question of what comics I might draw. It's what art forms I might invest in. I come from a background of playwriting. And directing. I sort of have regrets that I've never been able to get back to that. And who knows? I might still try to do that. When I was in college, of course I did cartooning for the college paper and I was working with college theater, but I thought of myself pretty equally as a writer as well as a cartoonist. There's a part of me that would like to explore other media. Frankly, the comics form is so labor-intensive, particularly for someone like me who's not real fast. There are various topics that I have feelings about that I would like to explore. When I think about trying a really large subject like

Stuck Rubber Baby, my feeling is I don't know if I have the stamina for that again.

SPURGEON: You mention playwriting. Do you think your cartooning has been informed by that in a specific way or ways? We talk about writers in general that come and work in comics, but I'm not sure how much we talk about cartoonists with a background on stage. Do you think your work reflects that interest? Certainly your early work has that proscenium feel that a lot of strips had. Do you see a playwright in your comics, Howard?

CRUSE: Yeah, actually. Quite a bit. My interest in dialogue and conversation as opposed to fistfights [laughter], I think that comes from being interested in a medium where everything is about what people say and what they don't say and what the subtext of relationships is. Those are the things that really interest me about the human experience.

I'm much more interested in developing characters in whatever medium than in drawing pictures. I'm not someone for example that's compulsively doing a sketchbook. That's a way I would be different from -- there's many ways I'm different from

Crumb, and that's one of them. [Spurgeon laughs] I like to draw when I have a reason to draw, but I don't sit around drawing all of the time for myself. I do spend a lot of time thinking about everything from politics to human psychology to the various ways that the human race is going over a cliff. [laughs] And not just fiscal. So there's a lot of things always stirring in my head. But it's not enough to have opinions about things. Everybody has opinions about things. For it to be worth a reader's time, you need to have some way of addressing a topic that is not just another, "Ooh, this makes me feel mad" situation. There needs to be an angle, and those are kind of dependent on your muse.

SPURGEON: Does your creative background have an effect on the way you work at all? As a playwright, you might be used to using dialogue to build out to scenes, and from there to acts. Do you work with dialogue differently on the comics page, do you think, does your work come more from the dialogue than maybe page structure or page design?

SPURGEON: Does your creative background have an effect on the way you work at all? As a playwright, you might be used to using dialogue to build out to scenes, and from there to acts. Do you work with dialogue differently on the comics page, do you think, does your work come more from the dialogue than maybe page structure or page design?

CRUSE: Oh, definitely more than a page design. My feeling is that whatever the visual look of a particular work is, it rises to the content. There are different ways of approaching page layout that are entirely related to the content. What's the mood? Do you want a lighthearted mood? Is this something serious? Is it mainly a narrative story? Is it surrealism? All of these things will cause the drawings to have a different look. In the case of

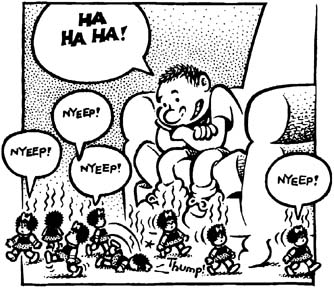

Stuck Rubber Baby, different scenes are staged in different ways depending on the content of that particular scene. My background is not only in playwriting but also in directing, even though in most cases what I was directing was my own plays. But to me, when I draw a comic book story, I am playing both playwright and director: staging it, deciding how best to stage something for the dramatic effect or the comic effect that I'm after. So I always thought this very much came out of my playwriting. This was even more so in the early days when I was doing

Barefootz. As you noticed, there's a certain proscenium feel to

Barefootz because the characters are almost always seen with their full bodies standing... the reader is on a eye-to-foot level, like an audience would see a play. I always thought of my characters as a repertory company, one that was performing this ongoing allegory about the experience of being alive and all. So that was very consciously stage-related.

It's possible that once I abandoned doing everything from that single perspective, you could say we've moved into more cinematic cases. In the world of movies, I'm a fan most often of independent films where it's all about what's the passion of the writer and director. I've never been able to do comics just to do comics, because I bore very easily. I need to care about what's going on. Something has to stir me. The themes of my stuff have typically been things I'm angry about, or things I thought were of the mysteries of life. Religion, etc.

SPURGEON: I thought it was interesting that in this new book when you discuss the overall look and design of

SPURGEON: I thought it was interesting that in this new book when you discuss the overall look and design of Barefootz

, your admiration for that being a design that works is expressed in terms of its mystery. You didn't break down how it works for you, or why. Do you have a sense of why certain character designs have worked for you in your career, and why other ones maybe haven't worked as well? I think that's a general strength of yours, that your characters pop on the page. When it works, what works about a Cruse character?

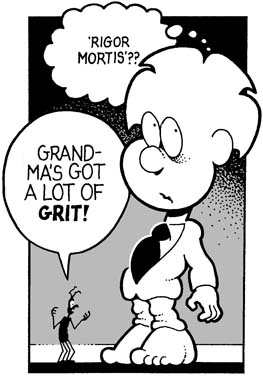

CRUSE: I'm not sure I would know the answer to that. What I learned during the experience of doing

Barefootz was that the character designs worked well for my initial concept of the series, but as I got more ambitious about wanting to deal with grittier subjects, it became an uncomfortable... the way the characters looked became increasingly uncomfortable because they could not... they were better at standing around talking or playing with the cockroaches or something [Spurgeon laughs] than action. As soon as you took them outdoors, outside of Barefootz's apartment, and then you started having to decide, "Okay, if the characters are shaped like this, what are their cars going to look like? What about their buildings?" You start running into things that make it impossible to build a normal world. The fact that Barefootz would not be able to reach the top of his head. [Spurgeon laughs] He might be wearing a hat, or he might be not wearing a hat, but you'd never see him put on a hat. [laughter]

There was so much dislike of the character designs from my peers in underground comix, and by that time I had already invested into that style for the comic book series. Many of them were not willing to go along with me on this notion I had on the dichotomy between characters that looked innocuous, as they might appear in the funny pages, but with a subversive subtext. I realized I had built a kind of trap for myself, inadvertently, about that. The time came when I said, "Well, if I'm going to deal with life in any kind of gritty way, I'm going to have to move out of the

Barefootz realm." The piece in the book called "Barefootz Variations" was my final wrestling with that dilemma.

SPURGEON: One thing that fascinated me going back over this material is that when you were you were using an essay format like "The Guide," when you were presenting a story to us through some sort of character-narrator or maybe just strong narration -- we accept that as a standard use for comics now, but I'm not sure how much that was a way of doing comics then. There couldn't have been a ton of comics like that. What were you looking at when it came to presenting things in this kind of personal essay form? How much of that did you have to develop on the page?

SPURGEON: One thing that fascinated me going back over this material is that when you were you were using an essay format like "The Guide," when you were presenting a story to us through some sort of character-narrator or maybe just strong narration -- we accept that as a standard use for comics now, but I'm not sure how much that was a way of doing comics then. There couldn't have been a ton of comics like that. What were you looking at when it came to presenting things in this kind of personal essay form? How much of that did you have to develop on the page?

CRUSE: It was happening. It was happening in underground comix. Crumb first and foremost was a pioneer in that. There were others. Those people opened my eyes to the possibility. Also the use of myself as a character in a mock autobiography... I became interested in the autobiographical comics form. A lot of the women were doing it. There was

Binky Brown Meets The Holy Virgin Mary, of course. That is the gold standard of laying your interior life out on paper.

I hesitated to do it for a while because I was insecure. I didn't feel my life was interesting enough for a comic book. Also seeing what Crumb did, I realized you could just pretend it was autobiographical. [Spurgeon laughs] Sort of the way

Larry David does in

Curb Your Enthusiasm, just let anything happen. So you could do something like "The Guide," and lure the reader into thinking that this might be an actual account of an LSD trip, but then you throw in that horrific ending. It's a joke on the reader, and it's a parody of the horror stories about tripping of that time. Once I felt free to just be crazy, and pretend I was doing stuff from my life, it became a lot of fun. It allowed me to make fun of myself. As I think I said in one of my essays, the nice thing about satirizing yourself is that nobody writes you an angry letter. [laughter]

SPURGEON: I liked the way the book was presented, Howard, with those short prose pieces. Was that through working with [BOOM! Editor] Filip [Sablik]? How did that part of the new book come together?

CRUSE: The actual editor that I worked with was

Adam Staffaroni, who recently left the company.

SPURGEON: Oh, okay.

CRUSE: He was the person whose enthusiasm for my work had encouraged Denis to represent me and get a book deal going.

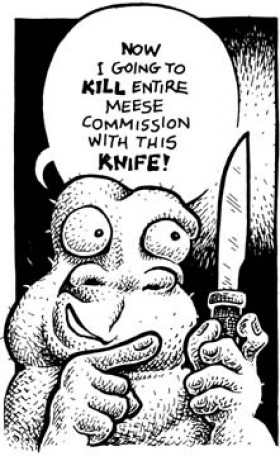

Some of the stories, just because they're topical, I thought there needed to be some sort of explanation. You have a generation of people now for whom the

Meese Commission on Pornography has no meaning. So that was an example of one where we needed some sort of explanation. Then Adam said, "I think throughout the book you should have little essays, explanations or reflections on them." I enjoyed doing those. It gave the book a chance to have new content no one had seen before. It's hard for me to judge how many people are interested [laughs] in my thoughts about these things, but Adam thought it would be a good idea, and several people have said they enjoyed seeing those.

SPURGEON: Do you feel that there's something your comics on the various subjects at hand

SPURGEON: Do you feel that there's something your comics on the various subjects at hand still

have to say today, even as the context has changed? We may not feel as much passion about the Meese Commission specifically, but there certainly remain echoes of those exact same elements in our society. We just went through an election period where there was a blatant attempt to place a 1980s template on a lot of the issues involved. Did you find going back and looking at this material, assembling the book, that a lot of what you talked about still resonates?

CRUSE: I think most of the things that interest me enough to go to the trouble of drawing pages of comics about are the larger issues in life. I guess you could say when I was doing short, episodic things like the individual episodes of

Barefootz, in those cases many times I was just interested in comedy, a certain kind of allegorical satire.

I would prefer that things not be dated. I think that in general, that's the case. Specific references, satirical moments in them, may make people say, "What...?" because they're not seeing the same TV commercials that were on at the time and stuff like that. In general, it's the large themes that are universal and timeless and interest me.

SPURGEON: Are you encouraged by the way these issues have progressed? Do you think there's been progress on topics like sex and censorship? Or are these things more cyclical? How do you feel about some of the subjects you engaged early on as they're reflected in the right now?

CRUSE: I think that as we discovered in this recent election cycle, things you think are settled, all of the sudden they bubble up again. Contraception of all things. I think there are always censors waiting in the wings. There are people very obsessed with controlling the world, and controlling other people. It's one of the dangerous aspects of the human condition. I think these things are cyclical, although when I look at the state of general society now as opposed when I was a kid in the '50s, there's no comparison. Great progress has been made. Simply looking at the ability of gay people to be visible as opposed to hiding in fear all of the time. The women's movement. All of the things that have changed in that regard. I think progress has been made.

It's also sobering to remember that the clock can be turned back. There was a very vital gay rights movement in Germany before Hitler. And yet it was pretty much wiped out. I think we always have to be vigilant about these things. We recently saw a production here of

Who's Afraid Of Virginia Woolf? I was reminded that when it first appeared on Broadway, it was considered incredibly foul-mouthed. It was something not appropriate to take a woman to. [laughter] Given the way the culture has developed since then, there's nothing in there anyone would blink at. I guess it was in the '60s when

Ralph Ginzburg went to jail for publishing Eros magazine. That was one of the rare instances where it was such an obvious violation of the constitutions, but even the good old Warren Court, which in general could be counted on to be on the side of the angels, dropped the ball on that. That's an embarrassment now to consider that this man was put in jail for having erotic pictures in a magazine. It's a strange contradiction in American culture, being both very licentious and very puritanical at the same time. It's always amazing.

SPURGEON: When I knew I was going to talk to you, I started thinking of your various contributions to comics. You were part of the underground generation, and right there with everyone else in terms of expanding what comics could do both formally and in terms of the content engaged. You have an acknowledged pedigree as a major and pioneering force in gay comics. You also have Stuck Rubber Baby

on your resume. This massive, critically-lauded work very much in the graphic novel category. I think of that book as one that presaged the kind of works we have in comics now more routinely. It was 1995 when that came out -- there was a flurry of similar works that year, but it was still very noticeable, and feels today like that was precursor to current publishing realities. I wonder if you could reflect a bit on Stuck Rubber Baby

as a publishing endeavor, this unlikely project. Do you get that sense at all, that just getting that book out there was an achievement?

CRUSE: I think the real amazing thing was that it was published by

DC Comics.

SPURGEON: [laughs] Yeah, that's right.

CRUSE: It's the only way it could have happened. During the '90s, it was becoming an article of faith among people who had followed the development of comics over the years that the comics form was waiting to explode with interesting, quality, smart stuff for grownups. Long-form work.

Eisner and others,

Spiegelman obviously, had laid the groundwork, and the field was wide-open for people do very ambitious stuff.

Stuck Rubber Baby was building on everything I had learned about doing comics in the undergrounds and doing

the Wendel comic strip for many years. It was a natural progression for me.

I think for a lot of people, if you were in comics, and if you were serious about comics during that period, the thought that was always in your head was if you could do a graphic novel and if so what would it be like. But the problem was that it was a practical impossibility for the most part to do that. I'm still amazed that so many people manage financially to do it considering how long it takes. I don't know how people do it. Maybe it's that they have spouses that are willing to be the primary breadwinners. Somehow or other it's becoming very common for people to do these great graphic novels. For me at the time time, when I quit the

Wendel strip the big question was what I was going to devote my time to. There was a year of doing little projects. I kept coming back to the idea of, "Well, I wonder if I could do a graphic novel." But every time I tried to think of a way to finance it, it seemed impossible. People like Denis Kitchen totally did not have the deep pockets to pay an advance that would cover the time it would take to do. I would fantasize about seeing if I could fundraise in some way or another. But it seemed impossible.

Martha Thomases, who was a publicist at DC, she's a friend of mine. She's the one who suggested, "Hey, you should check with

Mark Nevelow at Piranha Press. He wants to do interesting, experimental things." So I contacted him. It turned out he was aware of my work enough to let me come into the office and brainstorm a little. DC Comics, one thing in the comics field is they understand how labor-intensive it is and how much time it would take. A regular publisher would not have given me an advance remotely of the size DC Comics did. They think in terms of writers that write novels and don't have to draw the pictures for the novel. I had never made any serious money for anybody in my adult life, so I had no clout. DC was willing to take a flier on it because they wanted Piranha Press to be a genuinely experimental and groundbreaking part of the field.

As it happened, Mark Nevelow left the company about six months after I began the novel. They changed it to

Paradox Press -- all of these permutations that went on. Nonetheless, it was Mark that negotiated the contract and got the company on board with me doing it. And in giving me a substantial amount of creative freedom, which was the other thing that was special about that book being done by a company like DC. When Mark and I were talking about if this could happen. I said, "One thing you have to understand is I cannot work the way mainstream comics are used to working. It's not that I'm a

prima donna, it's just not the way I build comics." I build them in a very organic way. I do a little bit and a little bit there, and I'm always revising. I couldn't run into Manhattan every time I wanted to make a change. I told him that we'd do a working script, so that they could be reassured that if they put a bunch of money into this I would not end going down a blind alley and years later say, "Oops! I don't know how to finish this book." I did this script with the understanding that it was a blueprint I might change a lot. And indeed I did. They gave me essentially as much freedom as I had in underground comix. With the ground rules that this was not underground and I wasn't going to show genitals or anything. At least not erect ones -- I think Riley comes bounding down the hall naked at one point, but it's not a sex scene. So within the ground rules, essentially once they said, "Okay, we'll go with this working script," I would just draw a chapter to completion and bring it in. If there was a serious problem, or they noticed an inconsistency or something... when I turned in the working script, Mark made some suggestions that were worthwhile. Part of our agreement was that his editing would be suggestions, not demands. Kitchen would ask for a certain number of pages, and I would bring in finished work. Mark had more advanced warning than that. He had to understand that there was no point I wasn't making changes. I give him great credit for accepting that.

SPURGEON: I think it's such an unlikely story. We rarely stop to consider how much of a minor miracle it was for a work of that size and scope to come out in that age. You know, I wonder after you and the other members of the underground generation in a more general sense as well. You're all older now. Do you think your generational legacy is intact? Do we appreciate the undergrounds the way we should?

CRUSE: Oh, who knows? That's like asking if the young gay people appreciate the battles and sacrifices and stuff that were made. The women's movement is the same.

SPURGEON: Well... do they?

CRUSE: I think probably not. I think you kind of accept that. With each generation, the next generation takes for granted what the previous generation fought for. For me, one of the galvanizing, shocking events of my childhood was

the Kennedy assassination. Whereas for my parents' generation, it was

Pearl Harbor. For me, Pearl Harbor was this slightly boring thing I got tired of hearing about. [laughs]

The important thing about the legacy from the undergrounds is that the ground was broken and that young artists take it for granted that there's nothing out of bounds for the comics medium. I think that's great. I don't have a big need to genuflect to us old-timers. [Spurgeon laughs] It's a great thing for the art form, which a lot of people became excited about in those days. They've been proven correct in that comics really can deal with grown-up things worth the attention of serious readers of literature. I think short of a major book burning, I think that's a done deal. I think that's been proven, and new graphic novels come out every year that prove this is a vital art form. Now if people could just make money from it. That's the problem these days.

*****

*

The Other Sides Of Howard Cruse, Howard Cruse, BOOM!, hardcover, 228 pages, 9781608861002, July 2012, $24.99.

*****

* all images taken from the new book, cover image at top and design element at bottom, except for a single

Stuck Rubber Baby page I chose to show off how involved and labor-intensive those pages could be

*****

*****

*****