Home > CR Interviews

Home > CR Interviews CR Sunday Interview: Jesse Reklaw

posted January 12, 2014

CR Sunday Interview: Jesse Reklaw

posted January 12, 2014

*****

Jesse Reklaw

Jesse Reklaw is a veteran of the alternative comics scene, with almost two decades worth of work behind him (even this photo is ancient; I'm guessing it's from 2005 or 2006). Reklaw is perhaps still best known for his dream comic

Slow Wave, which was an award-winning alt-weekly comic strip and a pioneer of on-line publication. He has always been a prolific maker of mini-comics and 'zines.

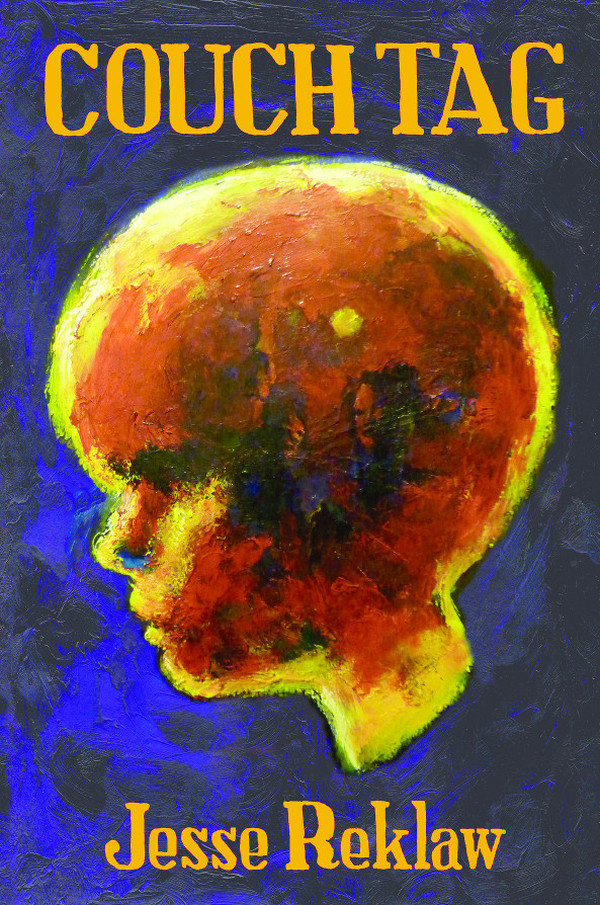

Reklaw released two significant books in 2013. The 32-page

Lovf New York: Destination Crisis from Robyn Chapman's Paper Rocket Minicomics was the first place many of us got to see a wild, painterly style that stands in stark contrast to the controlled, cool line for which the cartoonist was affiliated. The two styles mix in Reklaw's second major release, the remarkable

Couch Tag, just out from Fantagraphics Books.

Couch Tag is a searing memoir marked as much by its core instability as any single, dominant insight into the cartoonist's make-up.

We played phone tag a bit before finally settling into a conversation mid-December. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: Tell me about your daily life, Jesse. How much time do you get to make art? How much of that time is comics?

JESSE REKLAW: I have pretty serious arthritis right now. I'm still kind of struggling being diagnosed with bi-polar and taking a lot of meds and doing all those meds trials and then finding out that I'm a different person than I thought I was. So... I'm not doing a lot lately. [laughs] Honestly? I'm doing a lot of introspection, and a lot of sleeping.

SPURGEON: Are you set up somewhere where you can do this? Jesse, I've lost track of where you are. Are you on the West Coast? My guess is you're on the West Coast.

REKLAW: I am right now. I'm sort of attached to my girlfriend. I'm unable to care for myself right now. I can't even bathe properly. [laughs] Hey, girlfriends are nice. Or boyfriends. I'll take one of each.

I don't really adhere myself to any state or city. Whenever she's in Portland, I'm here. Whenever I'm on tour, I'm there. I look for friends to stay with. Right now we're living in New York and it's just really tough for me being a sensitive boy from California. That kind of culture is too visceral for me. I like to get out of town.

SPURGEON: You ended up in New York a few years back, as I recall. That's a reasonably recent development. When I say recent development, I do so acknowledging we're both at that age where we begin to talk in terms of years when we speak of recent events.

REKLAW: [laughs] Yeah, I know. It's really gross, Tom.

I'm not sure this is an interesting part for the interview, but the last three years have been a living hell for me. I'm one of those type-A, gotta work, gotta do it all the time guys, 14 hours a day, take on a new project kind of people. And I'm only able to work one to two hours a day. Sometimes I'm so tired I'll just sleep even -- I'm sorry, not that I'm

tired, but I'm so exhausted from the pain that I'll just sleep even though I'm not tired. So, you know [laughs] it's sad. I joke with my girlfriend I'm pushing to sleep 16 hours a day.

SPURGEON: You had work out this year -- so is this down physical period for you recent? Or is the work older and coming out during a fallow period?

REKLAW: I put out

a couple of minis through Robyn Chapman's Paper Rocket, and I may have had a few things in anthologies, but mostly they're commitments that I had made previously, or they were things I randomly did while I was just fucking off. So I haven't really taken on any new work. I'm trying to be as responsible as I can to the commitments I've already made. Those 60 pages or less that Robyn put out, that took me a year and a half. [laughs] I'm used to putting out 30 pages a month.

SPURGEON: Does that change your approach to the work itself that you only have this limited window in which to do it? Do you do change to a quicker style? Do you find yourself stuffing each work with more ideas than usual just to kind of express yourself?

REKLAW: That's interesting, I hadn't thought of that. That's likely. The stuff that Robyn put out was a sketchbook I kept with me when I had a manic freakout a couple of years ago and threw all my things away and told everyone I was moving to New York. Then I got bumped off my medication and so then I really had a thrill. [laughs] I just kept moving to different cities and calling different people my girlfriends and boyfriends... Meanwhile, I had this sketchbook on me and I tried to pour all that exciting adventure stuff they tell you to have into that book. Like you're saying, it's not overdone, but it's more finessed, maybe, than things I used to let myself get away with.

SPURGEON: How do you mean more finessed?

REKLAW: I would sketch in this sketchbook, and then maybe go back to a previous page and put more stuff on that and then find a to do list and say, "Well, that really doesn't belong in this picture of, you know, Satan, so I'm going to turn it into this group of dogs." I didn't want to see the paper, really. More than that, I wanted to look at that page and say, "This is done. This is a full, final [laughing] six-by-nine piece of colored paper and it's not going to get any possibly better so I should leave it alone." Yeah, I wanted to work on everything until I saw that working on it more would be a bad thing.

SPURGEON: A lot of your work over the length your career is strict deadline work.

REKLAW: Yeah.

SPURGEON: I think of you doing the alt-weekly strip and I think of you doing the diary comics, which both have an element of outside control. There is a very limited window in order to get things done, or at least considering the ways most people would approach such projects -- it's possible to work in a variety of ways, of course. But the way that most people work, there's a discipline instilled by a deadline or by the demands of keeping up with a daily expression. Was that helpful for you, do you think? Was that a structure you counted on all those years?

REKLAW: Absolutely. It's absolutely that. It was... well, you know, part of it started with

Slow Wave when I had a web site in 1995 and I was honestly trying to be commercial with it. I had a little catalog to sell things. It came directly out of 'zine publishing. In a 'zine you have your content, and it comes out regularly and then in the back you've got like a few things you sell, like a doll or a poster. I just tried to put that on-line. So I had to publish. It was publishing to me. Every week. I committed to that. [laughs] I did it for 15 years. [laughs]

SPURGEON: So the strip going away, was that just your changing artistic appetites? Had the market slipped away from you? How did you end up losing that outlet?

REKLAW: It was both of those two things. I was getting more into doing longer work. I've always been doing serialized comics, I love that format, and doing longer work. I think it just so happened that the serialized format is a more accessible format. You can fail three times in a row and then make one good strip and everyone likes your work. [laughs] Whereas if you make a comic that's 75 percent bad they're not going to like your work.

I found it easier to bite off these little chunks and to learn more there. I was putting out longer comics during that time; they just all sucked. [laughter] It's true! That first chapter of

Couch Tag was the first thing that I did as a long format work that my friends actually liked. That was very significant to me, because I'm one of those people that bounces around in my own head for a very long time. It's where I find a hole to ooze out.

SPURGEON: A couple of things run though your autobio comics from that period that I find interesting still. One of them is you were using those comics as a self-diagnostic tool, to kind of figure out what's going on in your head. That seems to be an element of

SPURGEON: A couple of things run though your autobio comics from that period that I find interesting still. One of them is you were using those comics as a self-diagnostic tool, to kind of figure out what's going on in your head. That seems to be an element of Couch Tag

, too, to help you figure things out.

REKLAW: It is.

SPURGEON: The other thing is this dissatisfaction with comics that you evince, the publishing options you have and the milieu in which your work is read and experienced. How you're able to create. That's kind of an interesting pair of things going on. The first one: is it clear to you looking back now what was going on in your head when you were doing those pages? I don't know that you ever look at the pages now.

REKLAW: I do.

SPURGEON: Was it a successful diagnostic tool for you, Jesse?

REKLAW: It was. It was very much. I had known I had depression for a while. But it wasn't until I started doing a daily mood chart -- which is something I added and bootstrapped onto the diary comic, and I'm really glad I did. For one, it made my diary comic a little more distinctive, and for another I got this mood chart out of it that clearly showed that I have a two-week up and down cycle as well as one that lasts about eight months up and then eight months down. [laughs]

I've been keeping a mood chart since

Ten Thousand Things To Do. I've got a good five years of it now. I can see I also have a three-year cycle. [laughs] I don't know. Maybe that just says that it's normal. We all have "milestones." All this stuff happened to me when I turned 40.

I think we all have cycles like that. I just think that my cycles are a huge part of my life, whereas they're not so big a part of the line of other people. I think that's why I ended up doing a random mood chart. [laughs] It's not the first time I've charted my mood. It's probably the reason I made serialized comics. I'm just very aware of moods all of the time. When I"m spending time with friends, I immediately check in with what moods they're in, and I notice I have friends that have wider mood variance than others. It's just something I'm interested in, I guess. And therefore that extends into my comics. If that makes sense.

SPURGEON: That makes sense... well, I'm not sure that makes sense. It's fascinating, though!

REKLAW: [laughs] That's very generous of you. [laughter]

SPURGEON: That's kind of a through-line for you, right? You try to figure out how you're thinking, why you're thinking. This is super-facile analysis, I know, but it seems like figuring out how you think is maybe the big connection between a lot of your work: you've done dream analysis, you've studied artificial intelligence...

REKLAW: Sure, sure.

SPURGEON: When you teach, you teach process. Which is a how-you-think topic.

REKLAW: You know what's gross? I not only teach process, but I've been teaching this class I call image science. It sort of started out as a

Photoshop class, but I got to the point where we were talking about computer vision and how we see and trying to get at a scientific approach to iconography. I've been extending this now not just into teaching Photoshop but to teaching penciling and composition from that same point of how the eye actually works. I'm trying to do some research right now on how we perceive motion, which I think would be a really great point for understanding comics transitions and montage in film. Not just from the -- I feel like the research into comics has been empirical. "A lot of people do it this way, so do it this way." I think it's interesting to look from a scientific point of view why we find comics fascinating. Not from a social scientific standpoint, but from the actual mechanics in your brain.

SPURGEON: As rich as that kind of material is in terms of it being an intellectual exercise, or as useful it might be in terms of self-discovery, does it change the way you're a patient? This constant self-analysis, does it help to negotiate the things that have happened to you, to be this conscious of how you process things? Has it helped?

REKLAW: I think it's helped me refine who I am. [laughs] I don't know which... it's sort of the tail wagging the dog. Did my nature turn me into myself or did my self have that behavior?

SPURGEON: Can you describe a way you think you're more yourself now that you have this knowledge? An insight that you have?

REKLAW: Oh, yeah, sure. Absolutely. As I mentioned before... it was very world-view changing when I took an anti-depressant. My level of anxiety... I have post-traumatic stress disorder from a lot of the events that happened in

Couch Tag. When my anxiety level came down to the point where I was not almost constantly disassociating, it seemed to me the world was more colorful, larger, more physically present and solid. I feel like I had been living in a ghost world for 40 years. It made me very sad for those 40 years I spent not really attached to reality, not understanding what people mean when they say they like sunshine. [laughs] I like to go outside in the park now, I appreciate nature, it's more accessible to me. Prior to that I was so inside my head all the time. Those were the things... I think this is common for people that have chaotic household environments or early trauma is that they fall into their own heads and get interested in fantasy or comic books. Role-playing games. The imagination. I think, interestingly, that trauma causes imagination. [laughs] Hope for something better.

SPURGEON: It's a way of negotiating what you have in front of you. So the material in

SPURGEON: It's a way of negotiating what you have in front of you. So the material in Couch Tag

, did it precede these realizations or come after? Where did Couch Tag

come in, the work that went into Couch Tag

, fall in this narrative of self-discovery?

REKLAW: Right in the middle. The freaking middle. I worked on the book for about five years. Then I had a personal epiphany about mental illness. Then I finished it in the next three. "Finished it." [laughs] I even had to get other people to help me to finish the book because I was so ill.

But yeah, when I started

Couch Tag -- I was telling my girlfriend Hazel this -- it was like a rant. You know? I was so angry at all of these people in my life that had abused me and abandoned me. It seemed like they had done it in such a subtle way. I had always been very quiet and... it's hard for me to engage with other people and tell them what I think without totally blowing up and screaming at them. [laughs] This was my way like you say to mediate my world. Say, "Here's my point of view about all of this, jerks." Then in the middle of that I had this breakdown and I saw that that those were all the reasons that I have a trauma. This is the way I look at it now. I was writing the book to rant because part of my symptom of bipolar mood disorder is to get paranoid and angry and megalomaniacal and I just want to [makes noise]

arraraarraraarh, I just want to yell at everybody about what jerks they are and so this is the book version of that.

When I finished the book, I really tried to undo a lot of that. My editor's view at that point as to the themes in the book was to take out the ranting and put more in of this sort of Freudian or Jungian psychoanalysis idea. I mean, that's sort of why I went with a book cover that look like a child psychology book or something.

SPURGEON: So there were actual physical changes to the comics?

REKLAW: Oh yeah.

SPURGEON: You went in and took out accusatory, slamming elements of it.

REKLAW: Completely. I threw out several pages that were way too angry. [laughs]

SPURGEON: You have to be talking about the personalizing of the anger, though, right, because [laughs] I mean, it's not any less a devastating portrait of a milieu. [laughter] It's not like you would high-five someone for being portrayed in this world, I don't think. [Reklaw laughs] It's a fairly damning portrayal, Jesse. I wonder... I wonder what was important to you in -- two things that are interesting about the portrayal in Couch Tag

are the thoroughness of it, and the slow-drip quality of it.

REKLAW: Thanks.

SPURGEON: You're dealing with these mostly innocuous elements of life, maybe outsized but not deeply troubling, and then the stranger moments off in the corners begin to seep into it more and more. Was that a deliberate strategy? Did you want to use like a slow boil?

REKLAW:

REKLAW: Like I said, that first chapter, "Thirteen Cats," was the first thing I had done in long form that my friends said they liked -- friends of mine that were famous cartoonists, so I thought, "Well, gee, I'm on to something good here; I'm going to make the book version of this. What people said they liked about "Thirteen Cats" I was going to do in a book format.

SPURGEON: Do you remember the switch that flipped that took you to "Thirteen Cats"? Did you just accidentally do it, or was there something specifically on your mind that that came out? Do you remember the conscious choice that maybe people responded to when reading the resulting work?

REKLAW: That was another manic phase. I actually did those 28 pages in about 20 days.

SPURGEON: Oh my God.

REKLAW: It was while I was running the distro

Global Hobo and preparing for

APE. So I was also doing the show display for APE to represent ten different artists, and scheduling all of that, and doing all my projects at the same time. I don't know if previous to that I had had some crack in my brain, some level-up moment that enabled me to be a better writer or if it was just one of those manic whirlwinds that I had in a manic phase that I was able to capture and write down and then later go back analyze it and say, 'How can I do that again?" To me it seems it could be either, or maybe those are the same thing.

SPURGEON: The striking part of the book, the obvious striking part, is that the book can be seen in two sections, essentially with a formal element to that. There are these tightly controlled, line-drawing, anecdotal autobio -- stories of various aspects of growing up. The second section is this expressive color, ragged approach you have. I would assume this second approach came after your second realization -- that this was not something you had planned to introduce from the beginning.

REKLAW: [laughs]

SPURGEON: I know, I know. That's why they pay me the big bucks, Jesse. One thing that's interesting about that is how you apply that second style -- you do go over some of the same issues, but from this different vantage point; it's almost a rehashing, or even a summary statement of that earlier section. Why have that second section in this work? In addition to it being obviously formally different it also seems like you're vacating a lot of the structure that you built to that point. I wonder after the choice of an author to end the book that way, the compulsion to do that.

REKLAW: Part of the compulsion is that I hadn't seen a lot of style shifts like that in comics. I think it's an area of artistic exploration for me, just like the science. It seems very fascinating to be able to change style like that so quickly because I believe that's very much how the mind works. We don't see a movie in our head, we see this weird morphing cartoon mash-up of thing. At least that's the way my brain is. [laughter] So I think that's interesting to explore on the page. It reminds me something my friend

Geoff Vasile says -- he's a great cartoonist and I'm sure you're familiar with his work. He's also a musician. He said he didn't want to do music anymore, he wanted to do comics, because most of the territory had been explored in rock and roll. In comics there are so many cool ideas that keep popping up that inspired whole genres.

Fort Thunder or something. That's so exciting to me, to see whole new ways of looking at narrative.

SPURGEON: So was there an outside source for the color work that went into the Couch Tag

book? Were you looking at anything that helped inspire or shape how that came bubbling out of you -- or was that part of a process very specific to you and you experimenting and working directly with color until you got to how you wanted things to look? Was there anything that inspired you?

REKLAW: Oh, definitely. I have a lot of influences, You know, I collaborated with a lot of them on that first

Lovf --

Vanessa Davis, and

Trevor [Alixopulos],

Hellen Jo,

Calvin Wong, Melanie Davis,

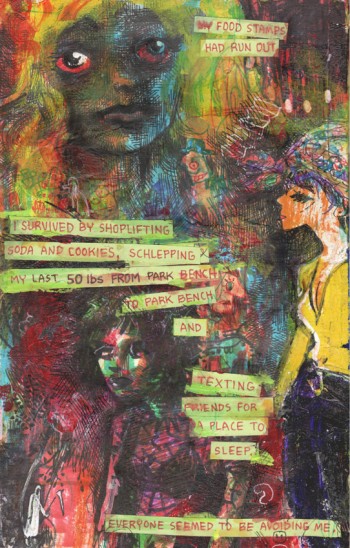

Damien Jay -- they're friends I've had for a long time that have similar sensibilities. We work in similar areas of comics. I saw Lovf as sort of a free for all, but I was trying to focus in on -- I was trying to push myself, draw in different ways and find the ways that work for me. It was deliberately a

Couch Tag practice book. I wanted to try out working with markers. I wanted to see how I could break the media, like blowing on Sharpies, adding in fingerpainting or collage elements. I wanted to come up with a toolkit of style I could then bring to the book. A mature style -- something I hadn't drawn in before, but a mature style. I knew I wanted a different style for the last chapter, I knew I wanted to work with style shifts. I didn't get to work with it as much as I wanted on this book because I was so ill, but I did get to do a few. The exact styles I ended up using come more from the internal changes and what my brain was doing at the time. The choice to do the style was more the... mentally interesting, more cognitive, less emotive.

SPURGEON: How confident are you in that style, then? How considered an effect are those that you get this way. Are you still feeling your way through certain expressive qualities on the page? The color section -- maybe even specifically the Couch Tag color section. You say you have a toolkit, but have you figured out what you want to do with it or is there an element where you're like, "Ah, I don't know"?

REKLAW: [laughs] Always. I don't think it's any less confident than the other style, which frankly I can't even do anymore. I tried to do a few pages in that clear line style, the real flat Lego-land looking figures, and I just can't do it. My biggest worry with the newer style is that I haven't been doing it as long and I'm not sure who I'm unintentionally ripping off. It looks to me a lot like stuff coming out of LA in the early 2000s. It looks to me a lot like

Lynda Barry. Other influences of mine. I just want it to be me and to be all mine. Or I'll drop it and find another style, I don't know. [laughter]

SPURGEON: Is it physically difficult, that style? I understand that everything is right now.

REKLAW: It's so much easier. I'm not doing that tight, controlled line. I really am fingerpainting, and the cross hatching is done from the elbow to get a feathered look, so it's not as pained. A lot of times I just scribble, especially with light colored pens. It ends up with a painterly quality where you have this big, scribbly blob of ivory color next to another one. It's great what technology has done with the marker movement is what I'm saying.

SPURGEON: Did that just work out for you that way, or was this partly a conscious desire to find an easier way to work. I know that a lot of cartoonists get into their late 30s and early 40s kind of cast around to get to an easier version of the same effect.

REKLAW:

REKLAW: Yes. [laughs] Me, too. That's what we're all looking for. This is hard work! I don't want to be too self-congratulatory, but I love looking at

Lovf. I will sometimes just pick up my sketchbook and look through it, look at my own drawings. It's for me. It takes me as long now. This is what I always do. I switch styles, and they take me a couple of hours, and then the more I work in that style the more it gets refined and then suddenly it's taking me 10 hours to paint a six by nine inch piece of paper -- which wasn't the initial intent. So then it's time to switch styles. I don't think I'm getting lazier in my 40s, I think it's just part of a cycle. I start a style, I take it to a point, and then I need to let it go.

SPURGEON: I thought the ending of the two sections in Couch Tag were fascinating in contrast. The ending in the more tightly controlled section is about the cookie jar. And the ending in the wilder section, the second section, it's more personally focused and specific. Is that a benefit of this new style? Does it make it easier for you to access these expressive moments. Does it make it easier for you to get at certain things?

REKLAW: It is a lot more expressive a style, yes. I think the worry there is getting to melodramatic.

SPURGEON: Are you happy with the ending, then? Because you go right into it there, Jesse. It's almost a personal credo.

REKLAW: Yeah... I was trying to capture not necessarily the voice but the mental outlook of a 19-year-old. So it was pretty emo, but I also knew I had to have a happy ending and that was about as happy as I could get.

SPURGEON: Why did you have to have a happy ending?

REKLAW: You can't have someone read a book like that and not give them a happy ending. [laughter] It's all commercial, Tom. Happy endings sell better.

SPURGEON: [laughs] This is a super-highly commercial book that way, Jesse, I can tell.

REKLAW: It is my most commercial book.

SPURGEON: You know, that's true. It's your biggest book as well. Was doing something large a pain in the ass? That kind of sustained, single expression? I mean, it's broken down into chapters, but it's not serialized small comics like we spoke of earlier.

REKLAW: I do not like pains in the ass.

I thought it would take me three years. I did two of the chapters in one month each so I was convinced I could do it in a few months -- I gave myself a little leeway there. If someone had told me it would have taken this long, I wouldn't have started. That's the thing with comics. Once you've made that commitment, you have to keep going. Like

Lady Macbeth.

SPURGEON: Hopefully not totally like Lady Macbeth. [Reklaw laughs]

I want to veer off a little bit. You mentioned Global Hobo. As much as this is a major work, and indicative of the amount you spend creating, there's an entire aspect to your time in comics that's enmeshed in how small-press publishing works. You were also there very early in digital, and I would imagine have some insight as to how that works. Do you have any perspective on the state of those markets? I saw you at CAB. Is this a healthy place to make comics right now?

REKLAW: Totally.

SPURGEON: Do you like it more now than the context that existed ten years ago?

REKLAW: No, I like them the same. They're different culture. I find the current culture a little too hard for me to access. I'm not as patient for animated gifs and I just can't look at a lot of these things. I don't know how people can read things on a tumblr screen. But I think what's essential for any comics era or movement or scene is some sort of free area. There was magazine publishing and then you had 'zines. This safe ground where anybody can get in there and learn the skills. I think that's necessary to let artists grown. Artists aren't going to really get hired to be lead editors at magazine. But they can make small publications, they can start a tumblr stream. When it's that accessible to publish, that's what makes a successful scene. I had that in the '90s.

SPURGEON: It seems your implicit criticism of the different contexts that exist for your work is that it doesn't always benefit the artist. Do you get worried about the publishing options you have now? Does it worry you, the options you have in front of you to find an audience for the kind of work you want to do? Does your attitude change?

REKLAW: I just read

A Drifting Life and I think, "I haven't got it so bad. This is all right." [laughter] It would be great if this country cared more about literature and art and working artists... as much as Europe does, that would be marvelous to me. I'm sure people in Europe are thinking of some Valhalla that's better than what they've got. It's always the same. You have to chase the industry. You have to chase the jobs. It's not horrible that I have to spend 10 or 20 hours a week doing illustration work or design or looking for change on the ground. As long as I can spend at least half my time as a professional cartoonist, I'm pretty happy with that. I'm getting to do exactly what I want. That's amazing.

SPURGEON: A lot of guys roughly our age have talked to me in the last year about finding a place to work -- a kind of variation on ambition where they realize they have a certain amount of projects they'd like to do and carving out a space in their life to get that work out there. I know the problems you talked about earlier are foregrounded in a way that your thinking might be different on this, but do you conceive of ambitions for your career? Is it project to project for you? Do you think about your work in that way at all?

REKLAW: It's very much about the books. I just see in my mind a dozen books that I have made and I'm just trying to get to that point. I think... I think I'm also doing that because of what I believe the direction of the industry is going to be. I don't believe in e-books. I think that that idea of the book has been around long enough that it's a good investment. I think there's a pretty decent royalty scheme for books and creative property rights that I can think of it as a sort-of retirement fund. [laughs] "If I make those 12 books, maybe I'll get a couple of hundred bucks a months to supplement my

SSI" more so than if I dumped a bunch of time into a web series.

SPURGEON: I watched you read some of your comics to people in a bar last Spring, as part of performance event. What do you get out of reading your comics out loud? You seem well suited to that, but I know that performing comics is not something we thought about in 1995, or if we did, I wasn't included in those conversations.

REKLAW: That's a very weird medium, and I don't know why I like it so much. I do like performing, I like performing to a small audience where you feel like you have a personal connection to everyone in the room. You feel like you can make jokes that appeal to specific people. That's very exciting to me to have all that attention. That's partly why I teach. That's partly why I'm in bands and want to be the lead singer. So it's really gratifying -- when I'm in the right mood -- to get up there and entertain. It sucks when your jokes are falling flat, of course. [laughs] That's the risk.

I think that could be the subject of an entire magazine. Power point presentations and readings and that kind of cross media -- it's a lecture and it's a comedy routine! I don't know. That's a weird space.

SPURGEON: One of the things I thought most interesting about

SPURGEON: One of the things I thought most interesting about Couch Tag

is knowing you're a performer, how much do you feel like you're on stage when you do autobio comics that way? Is there a way of making a case for yourself... is there a downside to having that performance aspect in works like this? Do you ever feel like you're getting yourself over at the expense of getting at the truth?

REKLAW: [laughs] Getting myself over?

SPURGEON: Ingratiating yourself with the audience, having the audience like you -- giving yourself a joke that maybe wasn't yours in the story being depicted, being generally attentive to coming across a certain way independent of the narrative... how do you find that balance between performing and exploring those truths about yourself?

REKLAW: It's a nice balance. My father was a performer and he said a lot of his performances went better if he came out and told a self-deprecating joke before he started insulting other people in the audience. [laughter] If he came out ranting about the world and how stupid everyone was, they didn't laugh at his jokes as much. I guess it's kind of that. It's like having a deep conversation with a friend. You give them some. They give you some. You say, "You did this wrong." Then you have to say, "Hey, I did this wrong." I think that helps build rapport. I'm willing to make that sacrifice. It causes me extra anxiety to think that somebody might come up and yell at me about the book, or call me a creep. Or that maybe one of my family members might appear with a bat. [laughs] Or a lawsuit.

SPURGEON: You've said you've had a hard time sometimes associating yourself with certain parts of your life. Do you feel that comics Jesse is a version of you -- or do you feel like he's a tool for you? Are you comfortable with thinking of him as you, as you being in the stories you tell?

REKLAW: I've been thinking about this a lot, Tom. About identity. Because I know who I am now. I know who I used to be and who I think I was. That's something I find fascinating about autobiography and something I wanted to capture in

Couch Tag. Not with the language, but the mental state. I can remember being a six year old and know what it's like to have that identity, but that's not who I am now. Who am I really? I don't know. Am I all of these things. Am I the integration of everyone I've thought I've been? Or am I the person I am right when I die? [laughs] That's the guy that gets the last say. The rest of you guys are wrong.

*****

*

Jesse Reklaw

*

Couch Tag, Jesse Reklaw, Fantagraphics, hardcover, 192 pages, 1606996762/9781606996768, December 2013, $26.99.

*

Lovf New York: Destination Crisis, Jesse Reklaw, Paper Rocket Minicomics, comic book, 32 pages, 2013, $9.

*****

* cover to

Couch Tag

* photo by me, I think at an old MoCCA Festival

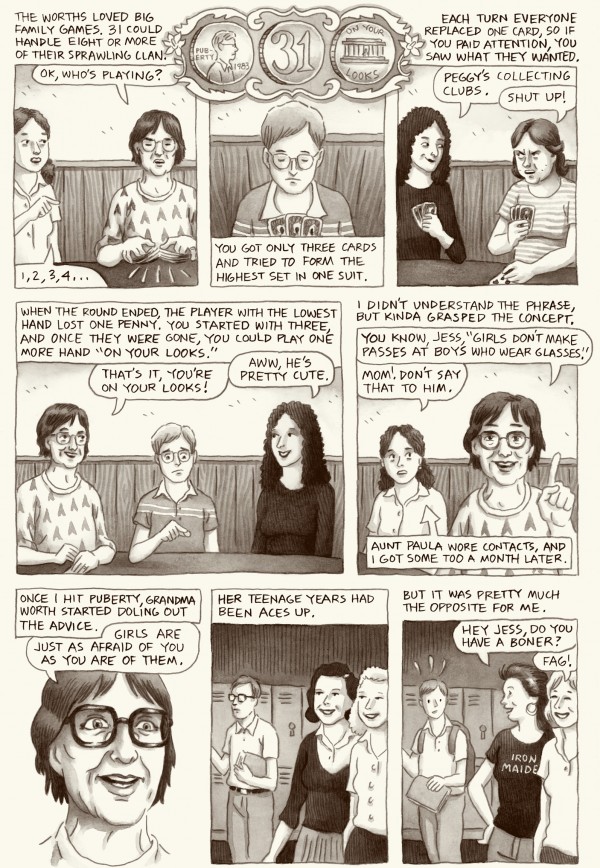

* an autobio strip with some of the tagging and iconography for marking certain aspects of his life at the end

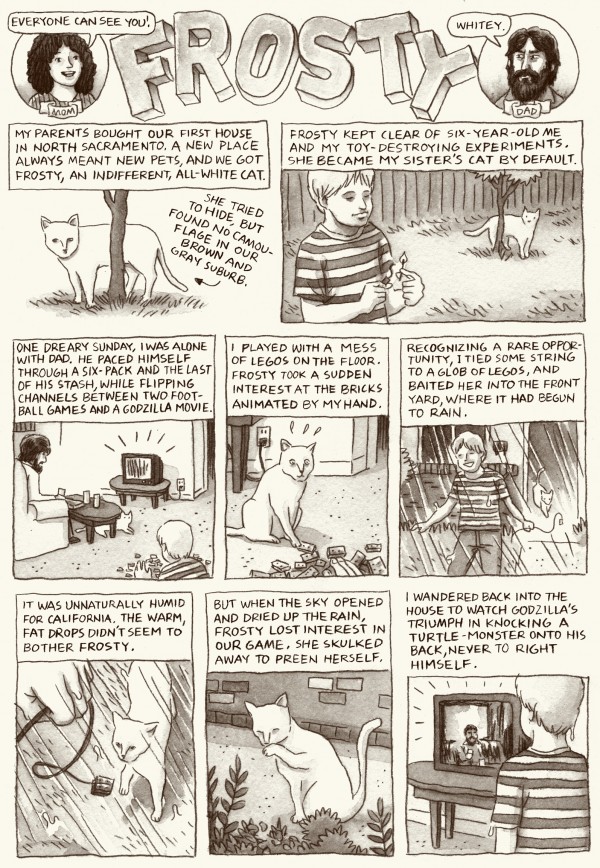

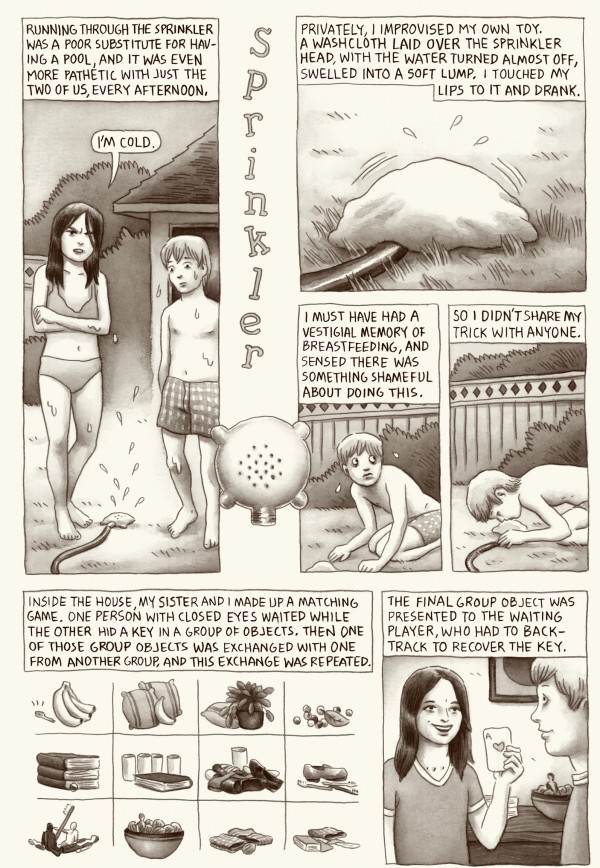

* three pages from

Couch Tag and one color work from

Lovf

* a panel from

Couch Tag (below)

*****

*****

*****