Home > CR Interviews

Home > CR Interviews An Interview With Ed Brubaker (2004)

posted September 2, 2006

An Interview With Ed Brubaker (2004)

posted September 2, 2006

Introduction

Introduction

In the midst of preparing for publication

last week's Ed Brubaker interview that focused on his brand new comic series Criminal, it dawned on me that I had on a hard drive somewhere another, longer interview with the popular writer that originally ran in the

Comics Journal about two years ago.

My thinking in putting it up today is that not only would it make a fine companion piece to the shorter interview, as Brubaker talks about a lot of the same issues from a decidedly different perspective, but it would be a fine piece to roll out on a holiday weekend as opposed to something brand new and perhaps publicity dependent that might suffer more than something classic from any slight dip in traffic caused by people being at the beach or the park.

I kind of fell into doing this interview.

TCJ Editor Gary Groth stalled on his Brubaker talk after covering the early days, and turned this over to me to complete five years later. Gary's contribution ran in front of this one as it was printed in the

Journal and is owned by Gary and the

Journal, so it is not republished here. One thing I remember about doing the interview was that Ed sent me a large package of books covering the breadth of his post-

Lowlife career; I read and then idiotically returned them, so for art on this piece you'll have to do with covers. I enjoyed talking to Ed very much, and I was pleased with the way the following turned out. I still am. -- Tom Spurgeon (Labor Day Weekend, 2006)

*****

Original Introduction: The Ed Brubaker Interview (2004)

I always knew Ed Brubaker more as a writer rather than artist, a cartoonist who it was rumored kept a writing journal instead of a sketchbook during the years we both lived in Seattle. Smart and personable, Ed seemed a natural to get work from companies like Vertigo and Dark Horse when they began looking for alternative comic book talents to write their stories and launch offbeat features. Given how emblematic his mid-'90s series

Lowlife and the related books

At the Seams and

Detour were for a certain kind of comic book by a cartoonist of a certain age, it's easy to forget that Brubaker was doing accomplished collaborative work from the start of his career. His

An Accidental Death with the talented Eric Shanower was one of the more solid straight-ahead short stories of the 1990s, weaving details from the lives of its military children creators with the broad, life-changing splash that a dead body makes on all who come into contact with one.

Brubaker touched all the expected bases at Vertigo -- icon re-jiggering (

Prez: Smells Like Teen President), Neil Gaiman spin-off (

The Deadboy Detectives) and high-concept Next Big Thing (

The Deadenders) -- before breaking out in a title with much of his own voice intact,

Scene of the Crime. With Michael Lark providing rock-solid, moody, yet unobtrusive art, Brubaker gave readers a straightforward mystery mini-series with characters clear enough and dear enough to launch a franchise. At the same time, he managed to build on many of the same issues of regret and moving forward that fueled his best autobiographical work. (With cartoonist Jason Lutes Brubaker also created

The Fall, an even tighter and more evocative exploration of favored issues and literary approaches.) Brubaker parlayed the obvious quality of his mystery work into a stint doing

Batman, which led to the minor miracle that was his revamp of

Catwoman into a readable crime book with an appealing lead. From there he co-created

Gotham Central, a police procedural where overtones of the incomprehensible nature of modern violence wears capes, cowls and clown make-up.

A brief sojourn into Jim Lee's WildStorm superhero universe in the formally playful

Point Blank mini-series led to

Sleeper, essentially a deep-cover mobster drama like

Donnie Brasco or Ken Wahl's

Wiseguy television show, with the added complication of superpowers. Now in its second "season" as a cult favorite,

Sleeper is the funniest, smartest goosing of the superhero comic in perhaps a decade. Brubaker brings a novelistic density to much of his mainstream work, favoring art in multiple tiers and skillful first-person narratives. When he changes things up with a specific formal touch, say the flashbacks sprinkled throughout

Sleeper or the shifts in character viewpoint that frequently livened things up in

Catwoman, the flourishes are seamlessly worked into a book's overall mood. Brubaker's comics feel different than everyone else's without ever calling attention to that fact.

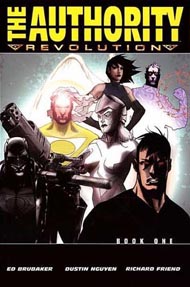

At roughly the time this interview sees print, Brubaker will be taking over writing chores on

The Authority and Marvel's

Captain America, two higher-profile, more straightforward superhero assignments that may move the 38-year-old into the first rank of mainstream comic book writers. He is also finishing a mystery novel and mulling over work in the videogame and film industries. Ed Brubaker sounds happy and grateful but fully aware how much hard work was necessary to make the unlikely shift from alternative comics supporting player to mainstream comics lead. He tells entire stories with the ease some people work through a single sentence, and is twice that friendly in person. -- Tom Spurgeon

****

Five Years Later

TOM SPURGEON: Every time I talk to you, you seem to be working so hard. Do you ever get away? I know writers will sometimes suddenly realize they haven't had a vacation in eight years.

ED BRUBAKER: Yeah. We've been living here three years, and other than days we go to town to deposit checks and do some shopping, I haven't really been away from the house for any real length of time that wasn't some kind of family emergency or business trip. It was 110 degrees here one day and this plumber who was doing some work for us said he and his wife were going to go to the river right after he finished fixing our sink, and he invited us to go with them because I said we'd never been to the river. I realized it was the first day in five years where I'd just sat around and done nothing. Without feeling guilty at least. I have a lot of days where I don't get anything done, but they're not on purpose. [laughter] There are days when you plan to get something done but you get distracted too early and you never end up getting anything done and you feel like shit.

SPURGEON: How do you work?

BRUBAKER: When I worked as a cartoonist I'd try to work in the morning before I could get distracted or I'd try to work at night when no one's going to call. But my schedule now... until a couple months ago it was pretty much I would get up and be working by like nine or ten and work through until two or three in the afternoon, and then if I had more to do I'd work ten to midnight, too. But the last couple of months I've been working sporadically, like I'll be taking notes for something for a few days and sitting around and wasting time and reading books and stuff, and then I'll hammer through some scripts really fast after I've got the outlines worked out. I don't prefer to work that way, but I've been having to travel a lot the last couple of months and it's been hard to get into a rhythm.

SPURGEON: So you tend to work from notes to outline to script?

BRUBAKER: Yeah... it really depends on the project. If it's something I'm totally creating myself, and not something like

Batman or

Catwoman... with books like that, you kind of have this idea of where you want to go and you try to map out a few storylines and you kind of spitball it as you go, it seems like.

SPURGEON: [laughs]

BRUBAKER: I don't mean it in a bad way, but it's episodic fiction. So if you've got a basic thing you're building towards, you don't need to take that many notes, you can work out each issue one at a time. I usually just write a page of notes of everything that needs to happen in a storyline, and then a more detailed page for each issue of it, like a page by page list. Sometimes, depending on the comic, that list is all notes about what the characters are thinking as opposed to what they're doing. Once I have that worked out, I go straight to writing a script.

SPURGEON: Now forgive my ignorance, but is there some kind of feedback process with editorial?

BRUBAKER: It depends on the book and the editor, but generally once an editor has an idea where you're going with a storyline. With Shelly Roeberg, she would want a pretty detailed idea of what was going into each issue. She would give you feedback. It really depends on the editor. With a lot of the stuff I'm working on now, with

Catwoman I've been working on it so long, I think I've told my editor things that are going to happen so long ago he probably forgot. A lot of times he'll be working on the solicitation and he'll be like, "So what happens on that issue?" We've been working on the book for so long that we've started to take each other for granted on that. Usually I'll get notes from him after I turn in a script if he thinks a scene isn't clear enough, or something, but generally other than talking to him over the phone about where I'm going with the stuff there's not a lot of feedback ahead of time.

Most of the editors kind of hire me to do my thing, and once we've talked through what direction I'm going to go occasionally I'll have to type up some notes about what the project is going to be, but generally I can get away with some light detail stuff about what I'm going to do and they just kind of trust I'm going to do it.

SPURGEON: Do you prefer that freedom, or would you like more feedback?

BRUBAKER: It's weird. You never really want feedback, but sometimes feedback is good, anyway. It really depends on the editor. Mike Carlin took a project I wrote and gave me feedback on the outline, and a couple of those notes sparked me to think in a different direction about a couple of scenes, so that was really helpful, actually. So it really depends.

For comics, once I've got an idea what I'm going to do now, especially some of the mainstream stuff, it's nice to work in an industry where pretty much you write something and it's the way it gets printed. I don't know anybody who works in TV or film where the final product comes out anything like they want it to.

SPURGEON: That's every medium other than comics, I think.

BRUBAKER: Some independent filmmakers, I guess, but I bet a lot of them compromise for budget. But with comics the only compromise is do you want to make a good living, and if so you're probably going to have to write some stuff that's not exactly the kind of work you'd write if you could write whatever the hell you wanted.

SPURGEON: How much work do you do? Say in a month.

BRUBAKER: I usually write about three scripts a month. The last year it's been about three scripts and every couple of months I'll have a month where I write four or five because I have to. I should write three or four every month to keep on schedule with everything.

SPURGEON: How full are your scripts?

BRUBAKER: I write scripts for other people a little bit more detailed than what I wrote for myself. Not that detailed. If it's a script for a 22-page comic, I rarely run over the 22. Maybe 25. Sometimes. I see scripts from other writers and some of them will turn in scripts that are 48 or 50 pages long. And then you read it and you wonder how the artist can possibly handle -- you look at those Alan Moore scripts, and it's like, "How can an artist get that?" I don't put in nearly that kind of detail. I just tell them what they need to know. [Spurgeon laughs] I'm not trying to criticize Alan Moore, but coming from the point of view of someone who was an artist first I just try to write the scripts and leave the fun part for the artist. I don't want to tell them what the grid looks like, or what all the camera angles are. The more you can leave for them the more fun they're going to have with it and the more they're going to get into it.

Image Isn't Everything

SPURGEON: Am I to take it you worked script first as a cartoonist as well?

BRUBAKER: Yeah. I never did sketchbook cartoons or just made stuff up as I went along. I always had a script. Which is kind of weird, because I always considered myself one of those guys who only wrote because I needed something to draw. When I was a teenager I started writing my own comics because no one else was going to.

SPURGEON: And now you make a living writing comics for other people to draw. How does that feel?

BRUBAKER: It's a little strange sometimes, to be working in mainstream comics, because I stopped reading mainstream comics in the late '80s and started reading them again in like the late '90s because DC started sending me a lot of them, and friends that I have were starting to work at Marvel and DC and I'd follow that stuff. I don't know if I'm completely immersed in it the way some fans are, but I'm actually pretty familiar with a lot of what's going on in mainstream comics now, and I wasn't at all in 1998.

SPURGEON: If you had to pick a time period to miss...

BRUBAKER: Yeah, exactly! '88 to '98 sounds like a pretty good time. I remember when I was living with Tom Hart and he brought home a stack of Rob Liefeld Image Comics -- I'm pretty sure it was just a bunch of

Youngbloods, it was the year that Image came out and was like super huge. I was working at a gas station in Seattle, I think. And I remember all these little kids coming into the gas station with comics and they were all Image comics. And I was like, "Oh, I do comics." They were all, "Really? What do you do?" I was like, "I don't know. What do you like?" "

Youngblood." "Well, I'm Rob Liefeld." They're like, "No, you're not! Your name's Ed!" [laughter]

It was totally funny, because I know three years later none of those kids were reading comics, and they had multiple copies of everything they were buying. They were baseball card collector kids. The kind of kids that ruined comics, basically. [laughs]

SPURGEON: They were good to Rob, though.

BRUBAKER: Yeah. [laughs] He made out like a bandit. I remember Tom brought a lot of those home and we were looking them like anthropologists or something. I hadn't been reading mainstream comics for at least five years. Just looking at these Image comics, these

Youngbloods, and trying to make sense of them... [laughs] "How can they go from a splash page to another splash page without an establishing shot?" [laughter]

I missed that stage where comics evolved into that. I stopped reading mainstream comics in that dark time after

Watchmen where everyone was trying to be super grim and gritty and all comics had nine panels a page. But then all that Image stuff happened where everything was a double-page spread and a splash page. I don't know how you can get the storytelling in that way.

SPURGEON: Storytelling? [laughter]

BRUBAKER: That's what people are paying for, right?

It was one of those moments where you realize that the comics industry is completely depressing. It's funny that here I am ten or 12 years after that working in mainstream comics and mainstream comics is just about as small as alternative comics was in 1992. Almost everybody I know who works in mainstream comics has a book they're doing that they're just doing because they really want to do it and everybody that reads the book loves it but the book doesn't make any money, most retailers don't order it. And that's just what alternative comics was like. [laughs] You'd wish you could get Marvel and DC off their shelves a little bit more so there was room for other books and now it's like that at the major publishers, too.

SPURGEON: You're currently making a transition into some work that might sell more in comic shops. Are there careerist motivations behind that?

BRUBAKER: Well... yeah. You want to be successful when you're doing anything, right? But the thing I have a problem with is that I don't feel like I've built up a big enough base of support among the retailers and fans to really carry just totally new stuff yet. Like I said, the mainstream market is really tough to crack right now for anything that's not Superman and Batman and Spider-Man. So eventually you look at that stuff and you think, "Well, all my friends are doing Wolverine and Spider-Man and X-Men, is that what's making their other stuff sell?"

SPURGEON: Do you mean you want the effects of branding?

BRUBAKER: I don't know if it gets new fans to your work if you do a big book like that. I'm about to do a book at Marvel [

Captain America]. I'm going to be doing

The Authority at Wildstorm, and both of those were conscious decisions on my part of like, "Well, I actually like these books, or the potential of these books, and I see something here I can do that's fun." But I'd also like to do more high-profile stuff so there's a bigger base of retailers who are familiar with my name. I think the fans will come to the books when they hear about them. With

Sleeper the trade paperbacks sell really well and a lot of that is from the buzz that the book was really good.

The fans will find you out. Warren Ellis' stuff does really well, and a lot of that is just word of mouth from fans for like five years. Still his trade paperbacks would move really well and a lot of it would be from bookstores. He would do decently in comic book stores, but he wasn't getting new comic book stores. We speculate that there are only a few hundred comic book stores in the country that actually order anything outside the top 20 or 30 books. So you really have to do something special to get the attention of anybody outside those few hundred retailers. Those other retailers, a lot of them don't put anything on the shelves, their customers have to subscribe to books. So the bulk of the direct market has become a glorified subscription service.

Every month when

Sleeper was coming out last year, I got e-mails from fans whose retailers forgot to o