Home > CR Interviews

Home > CR Interviews CR Sunday Interview: Jim Blanchard

posted April 8, 2017

CR Sunday Interview: Jim Blanchard

posted April 8, 2017

*****

It was my great fortune to work with the artist

Jim Blanchard in the

Fantagraphics office in the mid-1990s. Blanchard was an intimidating but forthright and friendly presence. There was never any bullshit on any level dealing with him even in the most casual way. Blanchard worked really hard, too, in an inspirational way for a 25-year-old wannabe writer to see every single day, ploughing furiously through an art direction slate that by then was almost entirely

Eros Comix-related.

I came to know Blanchard as an artist more gradually, primarily because of the expressed high esteem of his peers. He was great on

Pat Moriarity's pencils, and better on

Peter Bagge's. His own start-to-finish work doing portraiture, and these kind of decorative art pieces, and the occasional comic book I liked quite away and learned to love. As

Jim Woodring states in his effusive introduction, they are completely satisfying as virtuoso ink-slinging but jarring in their fullness as art. They are images that stick with you.

The parts of his career not the bulk of his portrait work is the subject of

Visual Abuse, a book that came out a few months back to almost no recognition by the comics press. I hope you'll consider giving it a look. There are a lot of fun, funny, profane comics in there, in the best of the tearing-down underground tradition. Blanchard's writing about his journey from a rich regional 'zine scene to early '90s Seattle and his maturity as artist across a range of styles and endeavors is as smart and to the point as much of the art. I will buy everything Blanchard does I can afford to own.

There's a nice, straight-forward and less wonky interview with Blanchard

here. I edited what follows slightly for formatting and flow. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: At the end of the book, it's explained that Visual Abuse

is a companion volume to Beasts and Priests. Given the amount of time since Beasts and Priests

, was there any consideration to just doing one big book both the graphics and portraiture aspects of your career?

JIM BLANCHARD: I didn't include the

Beasts and Priests material because that book is still in print, and was published by Fantagraphics. So there would have been too much in-print overlap. Also adding 64 portraits would have made

Visual Abuse too portraits-heavy, and unbalanced. I included the stuff from

Glam Warp -- another book Fantagraphics published -- in

Visual Abuse because that book is out of print.

SPURGEON: How does a book work within your overall professional landscape? I think of your freelance work as being built from commissioned illustrations, prints and maybe even original art. Does the book provide you access to a different audience? Is it a way of keeping this work out there -- Fanta does a great job of keeping stuff in print. Is it just personally satisfying? What do you get out of the release of a book?

BLANCHARD: The book was churning around in my head for over a decade. I had this 20-year body of work (1982-2002) that I felt no one had really seen, unless you happened to own it in its obscure original form, which was comic books, weird limited edition art books, magazine illustrations, record covers, flyers, posters etc. The idea was to collect and arrange all this stuff into a coffee table book with a brief written narrative to provide context, and give the art some new life and hopefully get it under the noses of people who had never seen it. Stoke the coals. So yes, with luck it will provide access to a different audience. It's already happened, I've heard from people who were introduced to my art through the book.

The format was inspired by

The Lowbrow Art of Robert Williams, which divided Williams' work into chapters based on styles and mediums, and adds a text introduction to each chapter. Another inspiration was

Art Chantry's

Some People Can't Surf, a book I've admired for a long time for its elegant layout and structure. I'm hung up on retrospective art books. "Why doesn't so-and-so have an art book?" Now I finally have an art book. It satisfies my art ego. And it's a relief to be done with it.

SPURGEON: I don't usually talk about the introductions, but that was an amazing short piece of writing by Jim Woodring. What made you think of him as someone who might provide an introduction? Is your opinion of Jim's work along the same lines of his opinion of yours?

BLANCHARD: Jim hooked me up big time and his introduction is incredibly flattering. I'm not worthy! I have enormous respect for Woodring's art. Having read interviews with him, it's obvious that he's a master of written/spoken language as well as visual language. He's one of the most unique, talented and bizarre artists around and I feel grateful to know him and consider him a friend.

SPURGEON: What led to the decision of your writing some contextual essays for the book? They're very strong, and they're a lot like your spoken voice. What was it like revisiting your material in order to write about it?

SPURGEON: What led to the decision of your writing some contextual essays for the book? They're very strong, and they're a lot like your spoken voice. What was it like revisiting your material in order to write about it?

BLANCHARD: Writing the text pieces was very difficult. It had been 25 years since I've done any kind of serious, concise writing, and it took me weeks to get my word gears rolling again. It also took me a while to establish a "tone" I was happy with. I'm still not entirely happy with it, but editor Eric Reynolds kept telling me it was OK. The text in most art books isn't typically written by the artist, so I'm uncomfortable with it being a first person account. Then again who reads the text in art books? I almost never do!

In this case, I think the context was necessary for the book to function correctly. I tried to keep it short and sweet. Having a computer made revisiting and organizing the visual material easier, however the text was hand-written on yellow legal pads.

SPURGEON: The descriptives for musical acts that aren't you: is that taken from old articles, or did people provide material just for the book? What made you want to bring in some outside voices there?

BLANCHARD:

BLANCHARD: Since I had access to good photographs from some of the shows I did flyers for, I solicited standout memories from people who were at the shows, to further augment the layouts. Many people I asked had no memories at all after so many years. I thought the approach of adding photos/memories worked out well and helped contextualize and "set off" the flyer/poster art. Some of the shows I did crapped-out posters for have become historically notable, such as the Nirvana Motor Sports Garage show. The night of that show I was offered but turned down an inch-thick stack of the posters, which are now worth hundreds of dollars each!

SPURGEON: You begin with music, which seems to be this significant force for you, particularly in the first half of your life. Can you talk a bit more about what the appeal was to music you listened to -- stadium rock at first, then punk, then hardcore/punk -- as an artist. You hint that these musical acts helped you find your way in this isolated town, but I don't exactly know what you found aesthetically appealing there.

BLANCHARD: Hard to really nail down the source of the appeal that music had on me. It's a groove that grabs ya and that's it. As an angry teen in stodgy Oklahoma, punk was a fantastic outlet. As a younger kid, I was also a fan of pro football, baseball, and basketball, so I think my appreciation of rock music early on has to do with a similar appreciation for action and physicality -- most of the rock bands I was into were physical: The Who, Hendrix, Grand Funk, and of course after that punk and hardcore were incredibly physical. In terms of visual aesthetics, when I was young the distinction between comics, pro sports, and rock music was blurred. They all had an attendant graphic language that was similar: cool logos, bright colors, "heroic" figures, etc. I was talking to cartoonist Ed Piskor about this at A.P.E. in San Francisco a couple years ago. His

Hip Hop Family Tree gets into that mixing up of "heroic" genres.

SPURGEON: One thing that interests me about your early 'zine experiences is that you had a bunch of local 'zines to see and know were publishing and from which get some practical encouragement. It seems like the regional identity was a selling point for Blatch

as you continued to work on it. How important was it for you to start your work simply where you were, when you had the ability -- or maybe even close to the ability -- to get started. Was there a crucial, driving motivation there?

BLANCHARD: Well, regarding starting the

Blatch zine, it was 1982, way before the Internet. At that time you got info about the music world from magazines and fanzines. I was immersed in that stuff, even though I lived in Oklahoma. My Anglophile brother subscribed to British music tabloid

Sounds, and I was getting countless punk zines through the mail. One issue of

Flipside would give you a pretty accurate impression of what was going on in the US punk universe at that time, through the reviews, interviews and advertisements.

To call early '80s U.S. punk rock "under the radar" is an understatement -- it was non-existent in the mainstream media. That was another motivation, to spread the news about this secret, rad shit. I think when

Fear appeared on Saturday Night Live and wrecked the place, it scared the hell out of the Powers That Be in the big media. The hardcore era encouraged participation. Texas punk band The Big Boys always added "now go start your own band!" to their flyers/records/etc. At that time, the different regional scenes had well-defined differences, something that's probably been obliterated by the internet. Texas/Oklahoma punk bands and zines were distinct from the ones from New York, Washington D.C., Los Angeles, etc.

SPURGEON: Jim, if you don't mind saying, why did you come to Seattle when you came to Seattle? You talk about seeing a football game at Peter Bagge's house that sounds like 80 percent of the comics scene at that time -- you were early, in other words, although maybe less so for the growing music scene.

BLANCHARD: I graduated from college in 1986 and knew I wanted to get the fuck out of Oklahoma. I lived at my parent's place in Bartlesville, OK for a year and worked construction to save some money. I picked Seattle because of a chick I knew there, and because Seattle seemed like a cool place. It was certainly affordable back then. And you could find a parking place. I arrived in the summer of 1987, so the Grunge thing had yet to blow up. There were a few cartoonists, but nothing like the tsunami of cartoonists that showed up in the '90s. I dig the Northwest and have been here since '87. I think I dig it because of the air and the green-ness. And there's lots of smart people here. I ain't moving any time soon. I love Bellingham, my current home.

SPURGEON: Was moving from Seattle proper a necessity, mentally or in order to better afford your pursuit of art?

BLANCHARD: It's sad to see what's happened to Seattle. Some of the highest rents in

the world. I think I paid $200 a month for rent when I moved there in 1987. Forget about buying a house. What you're left with now is tech workers; all the funky artists and musicians can't afford to hang. I suppose it's inevitable, though, and I'm glad I got to experience it when I did.

We left Seattle -- on Sept. 11, 2001! -- so my wife could go to Western Washington University and because we really liked Bellingham and had friends there. We left Bellingham for Maple Valley/North Bend in 2006 because my wife got a high school teaching job in Snoqualmie. We moved back to Bellingham in 2016. It's beautiful here but also pricey.

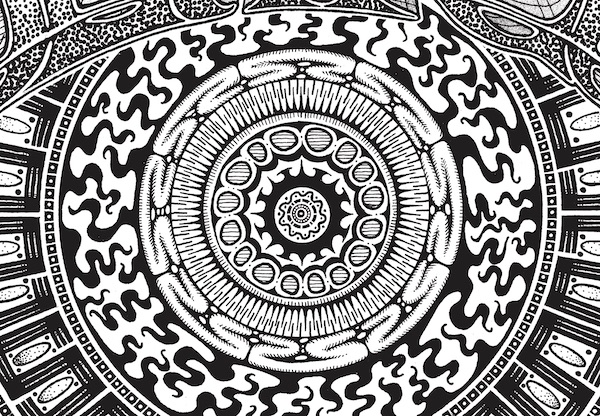

SPURGEON: You mention in your chapter on psychedelia that you were already doing what people later thought was drug-influenced art before you had ever dropped a tab. If that didn't come from psychedelia, where did that come from, that intense interest in filling the page? It's not an uncommon obsession for artists to have. When you talk about the art like that you'd having an extraordinary impact, what was the young you reacting to?

SPURGEON: You mention in your chapter on psychedelia that you were already doing what people later thought was drug-influenced art before you had ever dropped a tab. If that didn't come from psychedelia, where did that come from, that intense interest in filling the page? It's not an uncommon obsession for artists to have. When you talk about the art like that you'd having an extraordinary impact, what was the young you reacting to?

BLANCHARD: Again, it's hard to nail it down specifically where the obsession comes from, or what my attraction to it was. It felt good and I did it. Psychedelic art is usually very attention-getting in one way or another. Eye candy. I assume lots of kids liked it. As I mention in the book, I was definitely influenced by psych art I saw as a child: record covers, psych poster art, those dense ads in comic books and magazines for iron-ons, posters, patches, etc. Also certain Marvel Comics artists like

Jack Kirby,

Jim Steranko,

Jim Starlin, and

Paul Gulacy. I think of

Berni Wrightson and

Frank Frazetta as psychedelic. Trippy and organically fluid. That's the stuff that got me started. At age 16, seeing underground comix busted my noggin wide open.

SPURGEON: Did you become less interested in music and making art related to music in the 1990s? It seems like those gigs fade from your work at least in volume by then.

BLANCHARD: Part of that is because the production of "physical media" dropped off. There were less LPs/CDs/45s being made. Despite that, I've done music-related art pretty much continuously since the early '80s. Once those ties are established, you tend to get lots of job offers. I still enjoy doing it. Just finished work on two 45 covers and a flyer. Flyers are typically low pressure and a chance to work wacky/spontaneously. I never lost interest in music and am still preoccupied with it.

SPURGEON: I had a couple of Fantagraphics questions. The first is that you mention working in the warehouse with Michael Dowers. I know from the book that you encountered a lot of art that you admire that way, but I also know that you didn't always like every publication. Do you feel like the industry overall serves the kind of comics you like to do -- even if not by you? Do you feel like the desire to become legitimate has worked against a kind of comics-making you value?

BLANCHARD: I rarely read comics nowadays. Occasionally I'll re-read an old R. Crumb comic or Kirby-era

Fantastic Four reprint or something like that. But, I'm not drawn to them, so I don't really have any needs to be served by the comics industry. I see Fantagraphics' output when I visit their wonderful store in Georgetown, but that's about it. Most of the modern "indy/alternative" comics I see from the U.S.A. don't engage me. Too self-conscious and niceity-nice. There are a few exceptions. It seems like comics in America stopped evolving around the same time rock music did in the '80s and '90s, but I'm out of the loop so I could be wrong. To me, the last great comics generation was the group that came up in the early-mid '80s: Clowes, Bagge, Kaz, Friedman, Hernandez Bros., Burns -- all with amazing, unique artistic chops and all on a par with the best of the previous generations' cartoonists.

The last comic work I did was over 10 years ago: the

Trucker Fags In Denial comic published in 2004 -- new edition of that one is in the works, btw. I quit doing them because it was too much work and there was no money in it. Not my forté. Not any stories I really want to tell. I'm much happier doing singular illustrations rather than narrative art. I did become a more proficient artist by doing them, though. Making comics forces you to draw things and situations you wouldn't otherwise, which is a good exercise.

SPURGEON: How did working on all of those Eros Comix so quickly as a designer have on your work? I know that with strip cartoonist who have to produce a lot of comics, or comic book artists, a regular sustained gig will lock the elements of their style into place. Were you a different designer or even artist after doing that job so intensely for so long?

SPURGEON: How did working on all of those Eros Comix so quickly as a designer have on your work? I know that with strip cartoonist who have to produce a lot of comics, or comic book artists, a regular sustained gig will lock the elements of their style into place. Were you a different designer or even artist after doing that job so intensely for so long?

BLANCHARD: Working on Eros Comix -- and

the Monster Comics imprint -- was usually fun and low stress. There was way more room for silliness and gaudy type, compared to Fantagraphics' more prestigious books. Not to say I didn't give it my best effort, because I did. By the time I started art directing at Fantagraphics, I had a basic understanding of type design from doing the

Blatch zine, flyers, and record covers. But I learned a great deal more once I'd been there a while, by virtue of working closely with

Dale Yarger and Pat Moriarity, both of whom had extensive formal backgrounds in design. Dale Yarger taught me so much, I miss him a great deal.

Kim Thompson was instrumental, too, and I also miss him very much.

SPURGEON: Bonus Fanta question: can you talk a little more about solving Peter Bagge's art style as something for you to ink?

BLANCHARD: There was definitely something a little off in the first couple issues of

Hate that I inked. I initially approached it the way I had been inking Pat Moriarity's pencil art: with rather thick outlines. It took me three or four issues to figure out the best line widths and the best brushes/tools to use. Eventually it gelled. Peter has a peculiar, twisty drawing style with lots of tight curves that can be difficult to ink properly. Some of those

Hates turned out swell and it was an honor to work on them. It's too bad the "pamphlet" format is dead.

SPURGEON: I loved the number of comics we got to see in this book, even thought you sort of summarily dismiss your skill as a comics maker. One thing I didn't recall until I saw them again were some comics you did employing a really thin ink-line: "A Trip To The Hardware Store" probably being the most distinctive. That style seems to stand sharply in contrast with some of your more grandly ink-slung works -- is there a story behind that different style, or reason it wasn't used more.

SPURGEON: I loved the number of comics we got to see in this book, even thought you sort of summarily dismiss your skill as a comics maker. One thing I didn't recall until I saw them again were some comics you did employing a really thin ink-line: "A Trip To The Hardware Store" probably being the most distinctive. That style seems to stand sharply in contrast with some of your more grandly ink-slung works -- is there a story behind that different style, or reason it wasn't used more.

BLANCHARD: "A Trip To The Hardware Store" was an experiment, really. It's a true story. After the incident that sparked the story, I took my 35mm camera to the store and took a bunch of photos for reference. All the art is inked with a 4 x 0 rapidograph, which gives it a creepy, "dead" quality. I never did enough comics to establish a consistent style. Each one was done with a different visual and story-telling technique.

SPURGEON: One thing I like about your comics are the rubbery figures you use for your characters, just inches short of being grotesques. Am I right in thinking that there's a certain amount of energy you get from designing certain characters like that? They're kind of all over the place in this refreshing way.

BLANCHARD: The grotesque characters were probably shaped from years of reading R. Crumb and other underground comix. Also Peter Bagge, Drew Friedman, Big Daddy Roth, Basil Wolverton, Don Martin, Looney Tunes cartoons, etc. My whole life I've been making wacky faces with my own face, so there's a bit of me in there, too.

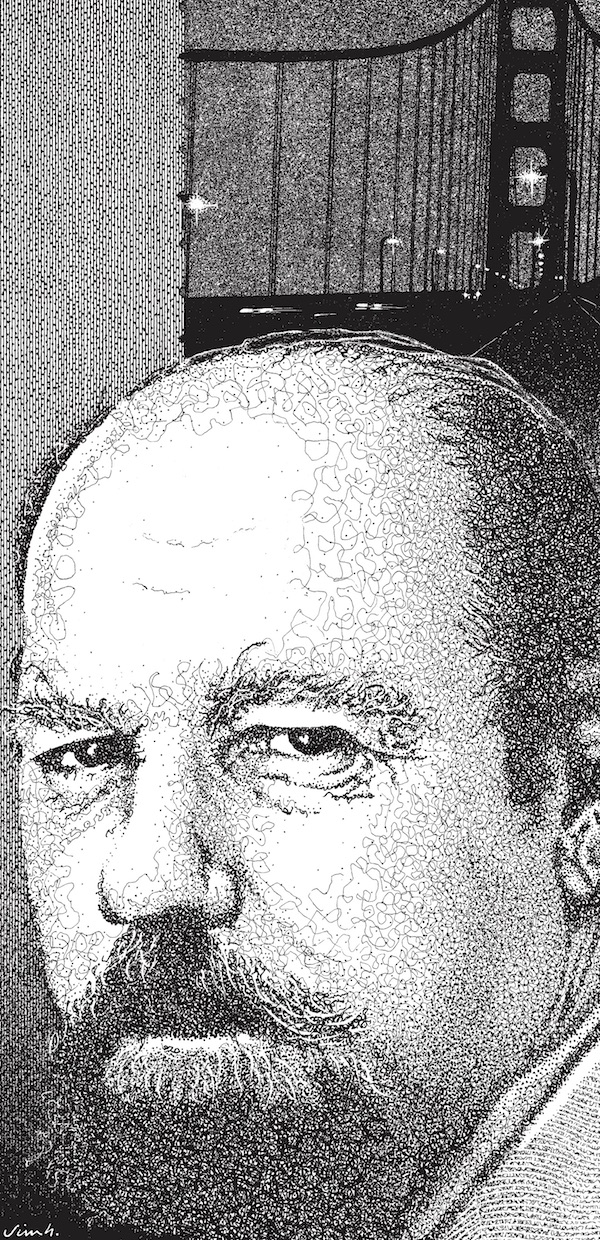

SPURGEON: The portraits we do see in this book show off a greater range than the hyper-photo look of the Beasts and Priests stuff -- although we get a few of those, too. The Charles Willeford portrait fascinates me in that the wrinkles and shading become this overt graphic element, which looking at some of the other portraits isn't uncommon at least parts of those pictures. How do you find a balance between bringing in that kind of abstraction into play and just hammering out the most visceral likeness of a subject?

SPURGEON: The portraits we do see in this book show off a greater range than the hyper-photo look of the Beasts and Priests stuff -- although we get a few of those, too. The Charles Willeford portrait fascinates me in that the wrinkles and shading become this overt graphic element, which looking at some of the other portraits isn't uncommon at least parts of those pictures. How do you find a balance between bringing in that kind of abstraction into play and just hammering out the most visceral likeness of a subject?

BLANCHARD: Back then, I had yet to solidify the photorealistic methods I use now, so the portraits were more exploratory and I was constantly trying out new things. Some of them are perhaps more "fresh" than the stuff I do now, because they are integrating more abstraction and taking more chances. I used to like to challenge myself graphically, and dig myself into a hole that I had to find a way out of. I wasn't always successful. I don't do that much any more. Now it's all about getting the work done. I've been meaning to find time to go nuts with paint out in the shed, and try some more spastic processes.

SPURGEON: Is it harder or easier to be an artist doing what you do than it was 15-20 years ago?

BLANCHARD: It's easier in most ways. I have a larger base of customers from over the years. I don't have to accept work I don't want to do -- I've turned down doing Trump for magazines several times. But it can be more difficult to motivate yourself when you've been cranking it out for so long. Also, my vision ain't what it used to be, so the mega-detailed pen & ink stuff can be a strain on the old eyeballs.

SPURGEON: Are there any untapped vistas out there for you, yet, something that might make a full chapter in a future book like this one?

BLANCHARD Untapped vistas? I'll probably keep with the portrait stuff I've been doing the last 20 years, and that suits me fine. I'd love to do another portraits anthology some day.

One future project I'm semi-excited about is a collection of my collaborations with Chris Kegel that Fantagraphics will be publishing -- maybe through their

F.U. Press imprint. The book will be called

Meat Warp, and will contain 100 pages of psychotic, porno and violence comix and art I did with Chris, none of which was included in the

Visual Abuse book. It should make for a stupid, twisted tome. Just what the world needs, right?

*****

*

Visual Abuse, Jim Blanchard, Fantagraphics, hardcover, 212 pages, 9781606999387, 2016, $34.99.

*****

* cover to

Visual Abuse

* photo supplied by Eric Reynolds

* some of that text

* that famous poster

* detail from a 1985 psychedelic drawing

* cover to Blanchard's own Eros Comix title,

Bad Meat

* from "A Trip To The Hardware Store"

* the discussed portrait of Charles Willeford

* from

Trucker Fags In Denial [below]

*****

*****

*****