Home > CR Interviews

Home > CR Interviews A Short Interview With Zak Sally

posted June 30, 2007

A Short Interview With Zak Sally

posted June 30, 2007

*****

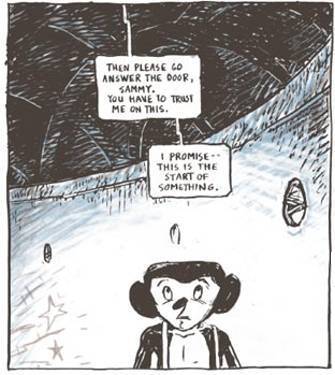

Zak Sally's

Sammy the Mouse may be the big surprise of the comics year to date. It's one of those efforts that makes you go back and reconsider the cartoonist's career output; it engages a larger percentage of the cartoonist's personality than earlier work allowed, and puts the full range of his artistic skill on display. Serialized in the art-friendly

Ignatz line,

Sammy should continue to press at the outer edges of Sally's talent. Although it's way too soon to tell,

Sammy feels like it has the potential to be a major effort.

Sally, in addition to being a cartoonist, a writer, and a musician best known for his stint anchoring the band Low, has also embraced comics publishing with

La Mano 21. He was so brutally honest about describing that venture I became worried about his emotional state. Even the moments of laughter described below were of the nervous variety, so after we got off the phone I called a mutual acquaintance to double-check if the truth-telling the Minnesota-based artist put on display was typical or aberrant. I was assured by that friend and Sally himself that he's more than fine, and remains positive about his new career. I wish fervently for the day when Sally and La Mano find their proper audience.

*****

TOM SPURGEON: It's been about two years since you've made the switch over to comics artist and publisher, a move that was covered at the time in various music and comics press sources. Now that you know a little bit more about the comics industries, how has your attitude changed?

ZAK SALLY: I think I'm probably a little bit more desperate. [laughter] I think I actually read this on your site: there's a weird dichotomy going on right now that there's certain things happening with comics that are great news for cartoonists and publishers. People are reading more comics; they're being taken more seriously: that whole thing all of us nerds have been hoping for for ages. But as far as that trickling down to actual cartoonists making money? The kind of money that people can live on? I feel there's a gap there that will take years to catch up.

SPURGEON: It sounds like you have a better grasp of things now, but you're slightly depressed by what you found out.

SPURGEON: It sounds like you have a better grasp of things now, but you're slightly depressed by what you found out.

SALLY: Maybe a little bit of that. I think the strangest part of it is that these changes are sort of glacial. These changes happen so slowly. That's the reality. It is changing. Everybody notices there is an interest in the medium outside the people who follow the medium. In the larger world there's more than a passive interest in comics as a means of communication or as an art form that's growing. How it's showing itself in real terms is strange and little frustrating. I don't know if that's any different than before. It's changed the way I look at La Mano, for certain.

SPURGEON: I know that you're coming at publishing from a 'zine background maybe more than a lot of the newer publishing ventures that come at comics from a traditional book background. I'm not sure there's been development for 'zine-like comics publishing concurrent to that for bookstores or even comic shops. It might even be worse for that kind of comic, that kind of distribution. Do you get any sense that the work you value has a place in this growth?

SALLY: Yeah. The whole thing about La Mano, from buying a press or even trying to take it up through different levels, was this deep-seated root feeling that these things have a place. And I'm finding [laughs] as I go on that having that feeling myself doesn't necessarily translate to actually selling books. My hope with La Mano is that I read something or a friend sends me something is that I feel this really needs to be out there. And my job is to figure out on what level it needs to be out there. I'm still undershooting and overshooting all the time.

It's not this feeling that it needs to hit everyone in the world. But when I put out the

Mosquito Abatement Man book, there's a feel that John Porcellino's work has importance. He's a really good friend. I don't think now, three years later or whatever after I put out that book, I don't think there's any question that John's work could appeal to more people than it does. But that doesn't mean I'm not sitting a couple thousand books in my warehouse.

SPURGEON: Do you do shows? Do you meet people at shows and hand sell?

SALLY: I'm finding I'm kind of shitty at that. [laughter] That's where for better or for worse La Mano's business sense, I'm finding that whether or not I like to admit it or not that's where my interest takes a precipitous drop. Working with this person on this project that I think is really great, after the project is gone, it's taken a long while to admit my interest drops. [laughs] Maybe that feeling that doesn't work to my credit, is that feeling that someday people will find out about this. It feels like I'm so busy all the time I can't breathe anyway, so spending more hours trying to convince people in a world that's already choked with people trying to convince people that shitty things are great, there's a feeling that people will someday find out about this, and when they do they'll come to me, and I'll have it for them. It's very warm and fuzzy.

That's the long way of saying that the way I think about La Mano is sort of changing. The new book I'm doing with Jason Miles, I'm doing everything in-house. Every element is done by me, so my cost outlay is virtually nothing. It's all elbow grease. It's an edition of 500 and I think everybody's going to feel great with that.

SPURGEON: What is about Jason's work that struck you? I like his comics quite a bit, too.

SPURGEON: What is about Jason's work that struck you? I like his comics quite a bit, too.

SALLY: Jason's a really thoughtful cartoonist. The new piece he sent me... I don't know, I read it and it hit me in the gut not in a way I can qualify. It felt like a strong piece of work. It developed from there. I told him it was a great piece and asked him what he was going to do with it. He said he wasn't sure. Two phone calls later, we had worked it out.

SPURGEON: How much of your time is split between cartooning and your publishing? How much time do you spend on your various comics and your publishing efforts?

SALLY: I wish I knew. [Spurgeon laughs] I think that's the great thing about my life, and also the most annoying thing about my life. My wife is in school right now and I have a two year old boy. It seems like every day is different. As I was finishing

Sammy the Mouse #1, things were such that I was able to devote a ton of time. I was able to come down to the studio every day for somewhere between four and eight hours. I was also pretty much out of my mind while trying to finish this thing up. So it felt like the family sort of suffered for me getting this comic done.

[pause] I think when I get back from MoCCA I might get a job at UPS, because it's a real amorphous thing, trying to deal with whatever comes up. A comic needs to get done, a strip needs to get done... it would be nice if things were a bit more standardized.

SPURGEON: You know, when I worked at Fantagraphics, they had been in existence for around 20 years, and they were just barely at the point where you couldn't automatically get someone at 2 AM by calling the office, the point where structure and accrued capital and managed resources were beginning to effectively buttress or supplant obsessive effort. That all-encompassing wall of work that needs to get done is very much a comics-culture thing. Even employees can get sucked into that, and find themselves working on the weekends, or staying around the office 14 hours a day. It sounds like you may be feeling the strain of riding your own version of that beast for a couple of years now.

SPURGEON: You know, when I worked at Fantagraphics, they had been in existence for around 20 years, and they were just barely at the point where you couldn't automatically get someone at 2 AM by calling the office, the point where structure and accrued capital and managed resources were beginning to effectively buttress or supplant obsessive effort. That all-encompassing wall of work that needs to get done is very much a comics-culture thing. Even employees can get sucked into that, and find themselves working on the weekends, or staying around the office 14 hours a day. It sounds like you may be feeling the strain of riding your own version of that beast for a couple of years now.

SALLY: I think I am. My view toward La Mano has been changing, and part of that is knowing it's always there. Between cartooning and keeping it going, I'm busy all the time. For me to try to get ahead of the game, even with the stuff I'm done, I know full well I could spend 40 hours a week doing promotion, doing things better. It just drives me crazy. I'm not even sure La Mano needs to be competitive in that sense.

SPURGEON: Ideally, what would you have your press be? You had very modest beginnings -- the name originally was just something you used for artistic projects you wanted to do. There was no business plan or artistic manifesto. Do you have in your mind's eye the ideal La Mano?

SALLY:

SALLY: When John and I talk, John talks about presses like

Black Sparrow. My goal I would love to hit with La Mano someday is to set up an infrastructure that was kind of like the early days of

Sub Pop to tell you the truth. That I kept the quality of work high enough through La Mano where people could trust the fact that if it was coming out from La Mano it was going to be a nice thing. And that it could just reach the people that it needs to reach on whatever level that is. That I could do whatever project I was taking on and the infrastructure was there to do that project justice. If it was an edition of 50 [laughs], I could do that well. If it was a book like John's, that it would reach a certain number of people. That it could reach its level.

It would also be nice if I could pay myself someday. If it could make enough to keep in existence, continue to pay the artists -- I've always paid my artists, and at a rate better than most publishers, I think -- and maybe, just maybe, pay myself someday. If it were ready for projects that came to it, and projects come to it in a weird way. I don't have any aspirations to be

Drawn and Quarterly. The more I have found out about the business thing, publishing and the book world, I'm kind of not that interested. I'm not interested in doing that sort of constant leg work to survive in that kind of industry. I'd rather hover around that industry. Some books are right for the book market, and some are not. Some are right for 'zines. I want to treat every project with that sort of in mind. But breaking into the book market is... you know... it's like being downtown and someone kicking you to the curb.

SPURGEON: Have you made attempts in that direction or are those avenues completely closed to you?

SALLY: I just fired up

Baker & Taylor and I'm talking to other book distros soon. But even to them I'm an oddball. I can't tell them I'm going to put out three books a year, but I don't know if I'm going to like three books a year, or if three books are going to be appropriate. There are people I've been bothering for years for them to send me their books, and it's going to happen when it happens. When it does... we'll see. [laughs] We'll see.

SPURGEON: Let's talk about Sammy the Mouse.

SALLY: Okay.

SPURGEON: If anyone is still left. We might have people weeping at their monitors at this point.

SALLY: Did I sound depressing about La Mano? Do I sound depressed?

SPURGEON: You sound a little depressed. What strikes me about your situation is that you seem to have an beneficial mindset. You have mostly attainable goals, and there's historical precedent in comics to wanting projects to find their market and then be willing to hang in there until you see to it that they do. Infrastructures are built on the bodies of previous books. Your goals depend on your hanging in there. But you're right, it's bleak. La Mano may be more ill-served by the nature of the market right now than any other publisher. And I'm not sure there are compensating actions you can take until some things are made apparent further down the line. You know?

SALLY:

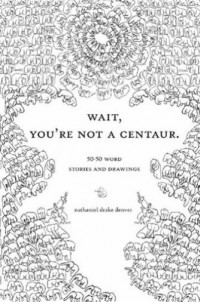

SALLY: I do. And to

not sound depressing [laughter], like I said, I feel this is about 100 percent true, for instance the

Nate Denver book. I read

this book, and I look at

this book, and to the core of me I think

this book should be selling millions of copies. Anyone you hand

this book to, across various strata of human beings, it has appeal. But from anybody's standpoint other than mine, it's kind of doomed. It's 50 stories, 50 words apiece, with drawing. And a full-length CD of music.

Barnes and Noble took other La Mano books, but this... they don't know if it's poetry, they don't know if it's supposed to be funny, if it's supposed to be not funny. It comes with a CD.

It's La Mano's blessing and curse. I like books that are neither fish nor fowl. As far as people making sense of it, I still feel like Nate is going to be famous someday and I think everybody should read this book. Thinking I can make that happen, I don't have any illusions about that. Not that it shouldn't happen, but I can't force it. I can only put it out and make it available.

SPURGEON: Here's something I don't quite understand. You're publishing John Porcellino... how does putting John's work into book form fulfill your publishing mission? Is it about finding an audience through a bookstore? Because not only is John's work singular and excellent, but the 'zine form is kind of perfect for it.

SALLY: I agree.

SPURGEON: Therefore in a way, your book is kind of less

vital than the original object. So are you just trying to facilitate sales through the book market, or is there something to this format that you find interesting in another sense?

SALLY: I think John wrestles with that a lot as well. It goes back to the beginning of our conversation about things finding their level. I am in agreement with you, and I know John is as well and most people that read

King-Cat as well, that the 'zine is the medium for John. There is no better way to experience

King-Cat. It's perfect in almost every way. But there was a feeling for me and I think for other people as well that more people should be exposed to John's work than solely the people interested enough to go out and find his work. Or that his body of work had grown to such a degree it might benefit from a different format. Plus there are issues of

King-Cat you just can't get any more.

I've said it a million times, but I think John's a really important artist. He'll cringe when he reads that. But I do. And in that way you want people to see it. You want people to know about it. But I agree with you. It's tricky. There are certainly times when I sit there... the

King-Cat Classix book is beautiful. It's got stuff I've never seen before. It's great. At the same time, it's such a different experience than reading individual issues of

King-Cat. It brings up that question. Maybe people should just buy it in the 'zine format.

SPURGEON: So is it just a feel thing, that you're giving up one aspect of someone's work in order to gain a certain amount of exposure?

SALLY: Yeah. I think the idea that's set in my skull is that

King-Cat the 'zine is going to be there. It's going to keep happening. John will do that the rest of his life. And those of us that know about it can keep getting it that way. And how people come to things... I used to feel differently about that, too. There's something about getting

King-Cat that's very pure. I know that's why John does it. He's directly transferring this thing into people's hands in this human, great way. In this way that means a lot to them. I don't think that's the only way for people to find out about it. Maybe it's the best way. Who knows what's going to happen in the world?

SPURGEON: In some ways these are unanswerable questions, too. Now: Sammy. I assume this is the 400-page story about the talking mouse you talked about in interviews a couple of years ago.

SALLY: It is.

SPURGEON: How does one get the call from [Ignatz series editor] Igort?

SPURGEON: How does one get the call from [Ignatz series editor] Igort?

SALLY: I didn't. I had finished

Recidivist. The whole reason for finishing

Recidivist was so I could get that out of the way and try something different.

SPURGEON: You've been really critical of your work in Recidivist

.

SALLY: I think it was what it was.

SPURGEON: Have those feelings changed now that you have some space between you and that work?

SALLY: I think I'd have to read it again. They're just really... [sighs] I think I was compelled to make comics that would drive me nuts. Those were the only kinds of comics I think I could make. Those comics made me want to put a bullet in my skull. You know?

SPURGEON: Because of their level of accomplishment? Their message?

SALLY: I think with the final one I was able to get some distance. But they're pretty bleak, you know? It was like I had a compulsion to put myself through the wringer with those comics. I couldn't not put myself through the wringer in a serious way to make comics. It got to the point I realized that and I realized you have to be able to do other stuff. It was like a punk band where the guy just yells and screams all the time. Who knows why? I knew I had to move past this somehow. I think that's what

Recidivist #3 was about. It's weird talking about things in this way, but it kind of worked. [laughs] I got done with

Recidivist #3, and I'm like, "Now I can make jokes." That's as serious as I can make things and as serious as I want to be. Ever.

So I'd been planning this thing, and working on it, and trying to figure out how I was going to do it. How I was going to make myself do this long story that I had.

SPURGEON: Tell me about that process. Are you working in a sketchbook? Are you writing stuff out? Are you making notes to yourself?

SPURGEON: Tell me about that process. Are you working in a sketchbook? Are you writing stuff out? Are you making notes to yourself?

SALLY: Yeah. I do have a notebook that's sitting around here someplace, with the first ideas I had about this thing. I drew this mouse when I was really drunk once. I sent it off to

M. Doughty who was in

Soul Coughing. I wrote this really hammered letter and sent it off saying, "Yeah, this is all I'm going to do from now on." Then the next morning I'm like, "I just sent off the only drawing I have of that great mouse." [laughter] I'm sure he threw it away. It was a joke more than anything.

Someday I'll do other kinds of comics. I've probably been taking notes for seven or eight years. Just kind of thinking about it. Probably thinking about it more than taking notes. At the same time, it seems kind of unreal. I'm kind of thinking about it, and about doing it, but to force myself to sit down and take this thing on, I wasn't sure how that was going to happen. So after

Recidivist, I saw these Ignatz things coming out. I was writing Eric Reynolds about something else. I thought I was going to do the

Sammy book on my own press, with the two colors.

SPURGEON: The band on the cover, is that because the original proportions were traditional comic book size?

SALLY: Nah, that was me trying... they're all going to have it. I think it makes it look classy.

SPURGEON: That would have been really cool if I had figured that out. [laughter] Now, at what stage were you when you knew it would become an Ignatz book?

SALLY:

SALLY: I was done with

Recidivist, and I was thinking about trying to pull this off. I think I was still in Low. Or I was just leaving Low or something like that. I kidded around with Eric and said, "I have this long story; I should do an Ignatz." He said, "Are you kidding, or are you serious?" I said, "I don't know, I guess I'm serious." He put me in touch with Igort. Eventually I sent a pitch. "This is what the story is, this is how long I think it'll be, this is what I have in mind." Eventually he wrote me back and said, "Yeah, let's do it."

SPURGEON: Is it still the 400-page epic? That seems to me big for an Ignatz book.

SALLY: It's at least eight issues. I'm kind of worried that it will go longer. It's at least eight issues.

SPURGEON: Is there an editorial process at all. Did you receive feedback at any stage?

SALLY: I've heard virtually nothing from anyone. I did the whole thing, and nobody read it before it was finished. At least the first issue. I sent it off... It's weird because I'm happy and excited about it. That's never happened to me before.

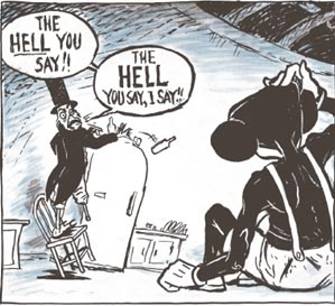

SPURGEON: This kind of anthropomorphic work isn't unheard of -- it reminded me of Ted Stearn's work a bit -- was there anything that specifically informed Sammy?

SALLY: Um... I have a list. [laughter] It's the normal sort of list. It's in front of me.

Crumb's Bearsies-wearsies,

Carl Barks,

EC Segar,

David Yow,

Kim Deitch... becoming friends with Kim Deitch has been sort of a big influence on allowing myself to be entertaining. It feels like for many years that was a dirty word for me. That if you were being entertaining you were that show Friends or something. That it was a bad thing. Talking to Kim and being a fan of his body of work made me feel like I wanted to tell a story and that there was nothing wrong with that. I think that more than anything... really watching Kim get this charge out of his work and telling his stories. There's certainly worse things to do in the world.

SPURGEON: He's an astounding cartoonist.

SALLY: Yeah. He works like crazy. Just seeing how into it he is, consistently. There's nothing he'd rather be doing. You just look at a guy like that.

SPURGEON: Did you have a similar feeling of being immersed at any time while working on this book?

SALLY: I think so. It was a little protracted. I think with any cartoonist, when you're doing the final push to get it done, it's usually not the fun stuff. It's that hard, difficult slog through getting it done. The writing and the sort of process... I'm in the second issue right now. It's exciting as shit. [laughs] There's always some point in the process where it's going to become painful and difficult to get it how you want it to be.

SPURGEON: One thing I think is interesting about the first issue is your approach to the page varies a lot.

SALLY: Yeah?

SPURGEON: You employ an almost dizzying variety of structural approaches. Full pages. Horizontal tiers. Vertical tiers. Backgrounds that connect. Pages with complex panel patterns. How do you approach the page?

SALLY: The only thing I can think of is that quote from

[Art] Spiegelman where all of his experimental work led up to him doing

Maus. I'm trying not to think too hard, you know? Your saying that about the panels and all that, I was like, "Oh yeah. I guess that's what I did." I'm actually drawing this thing, I'm scripting page by page. I'm writing it out, doing it on cheap marker paper. Roughing things in. It's really, really organic. I'm kind of working on the whole thing at the same time.

SPURGEON: You're not finishing pages, but going back and forth.

SALLY: It's like this big puzzle. I know I'll have a finished panel on this page that has to happen after this, and kind of working the whole thing at once until it finally gets whittled down into 32 pages or whatever. Trying to keep the next 100 pages in mind. I know A, B, C, D and X have to happen. I try to leave enough room. I'm really trying to have fun, you know.

SPURGEON: There are a lot of pieces of comedy in there. How do you look at those kind of bits of business? Once you got into doing the book, realizing you can entertain and do humor, how do you fold this routines into the wider aims you might have for the book?

SPURGEON: There are a lot of pieces of comedy in there. How do you look at those kind of bits of business? Once you got into doing the book, realizing you can entertain and do humor, how do you fold this routines into the wider aims you might have for the book?

SALLY: I think it was more just trying to figure out a way I could make comics. A cup that could hold whatever the fuck I wanted to put into it. I didn't set out to write bits or anything; it sounds so cheesy. But after what I was doing with

Recidivist and some shorts it's not like I'm some bleak dude that walks around all day eating his spleen. [laughter] I laugh at a joke as much or more than anything else. Why is my comic not strong enough to handle that? Part of it's that I came up with these characters and trying to think about them and what was going to happen. I'd come up with stuff that would make me laugh out loud. I figured if it made me laugh out loud, that was good. [laughs] I want to make a comic that's good.

SPURGEON: Something that struck me about this first issue is that you have a family now and that this book is very much set in a single person's milieu.

SALLY: Yeah. When all is said and done, this story is as autobiographical as anything I've done in my life. Yeah. I guess that's all I can say.

SPURGEON: It describes a certain kind of adult relationship based on convenience and proximity.

SALLY: I was talking to my friend today, and I think that's the other thing with this story. Getting used to the fact that whatever you do, whether you know it or not, you're putting pieces of your life into it that you're probably not understanding at the time. Instead of worrying about that constantly, and worrying about what I'm revealing about my rotten soul, and worrying that people are going to find out about what a dick I am, you just sort of accept that this thing is part of your life, and part of your life is in it. In many ways you're not going to figure it out until years later, and it's going to be really uncomfortable. It's kind of that I've read too many comics in my life, and I think that kind of really seeped under my skin. So I'm not thinking too hard about it. I have this language. You don't think about speaking English anymore. I'm letting every comic I've ever read, bad and good, turn into mash and I'm chucking it on the page. If it reads okay. everybody wins.

SPURGEON: How did you develop the process used to color Sammy

?

SALLY: You know how I was talking earlier about making everything really difficult for myself?

SPURGEON: Yeah.

SALLY: Kind of like that. [laughter]

SPURGEON: How are you coloring the pages?

SALLY: I'm doing a black line, and then I'm taking that black line, and I've chosen the two colors, and that black line is basically 100 percent of each color. Then I'm doing two overlays: one in blue and one in brown. I'm still working out the process. Yeah, I'm drawing each page three times. I'm probably going to continue doing that if it's really achieving what I'm going for, and I'm not sure it did with issue #1.

SPURGEON: Can you articulate exactly what it is you're going for?

SPURGEON: Can you articulate exactly what it is you're going for?

SALLY: Not exactly. I think in certain places that treatment felt a little flashy to me. It looked okay, but it felt in a couple of places like, "Hey, look at the process." I don't want it to be some sort of tricky thing that draws attention to itself. Ideally, what you'd be able to do is create a lot of different tones.

When you're working in graphite, nothing is actually 100 percent. So the way the different tones mix together would sort of give you a lot of layers to work with and two colors and a lot of depth. Looking at

Roy Crane, the way he used that old duo-tone paper. That's what I aspire to with two colors. Sort of making this thing that adds depth in a simple way. I'm going to have to keep messing with process. When it goes into book form, I know there are things I want to change. The panel inside the baby bar, that works all right to me.

SPURGEON: I didn't notice at all what you were doing -- granted, I'm not real quick to notice visual things -- until late in the issue when two characters are climbing some steps. That sequence seemed to call more attention to itself.

SPURGEON: I didn't notice at all what you were doing -- granted, I'm not real quick to notice visual things -- until late in the issue when two characters are climbing some steps. That sequence seemed to call more attention to itself.

SALLY: That's the part I was talking about where I feel like it wasn't as successful as I would have liked it to be. The problem with this process as well is that I'm doing it as two pieces of graphite over each other, so I didn't get to see how it would look until it was turned into those cover and put on top of each other. I thought those pages would be a lot more subtle than they turned out. I'm just trying to keep the bigger pictures in mind, and next time I'll have my process a little more streamlines and have a better way to come at it.

SPURGEON: Where did the gag with the rubber glove come from? I really liked that bit.

SPURGEON: Where did the gag with the rubber glove come from? I really liked that bit.

SALLY: It's happening with this issue, too, where I know that certain things have to happen, but I want to leave enough stuff open to have some fun.

I literally knew they had to get up there and do a couple of things up there. I drew the page, and knew they had to get someplace else. So two weeks passed where I had no idea how they were going to get off that thing. How are they going to get off? They can't climb back down. Somewhere in me there was, "He's going to blow up his glove." Cartooning or writing involves things you have to wait for. That made me happy than anything that I purposely sat down and planned out in my head. I'm trying to leave space for that kind of thing to happen.

SPURGEON: So what's on the plate right now?

SALLY: I'm doing #2. I'm really... I think my goal from here on out is to find a way I can work on it. It takes a ton of time and effort. I did have a teaching gig teaching comics for a while. I'm probably going to do more of that. Like I said at the beginning of the interview, in a perfect world, working on this would pay enough for me to eke out a meager living. But that's not the way it work. I'll keep working on it and try to get other gigs drawing. We'll see how that pans out.

SPURGEON: If we end the interview right here, we may drive dozens and dozens of people from the field.

SALLY: You should put "Zak paused and said, 'I'm fucked.'" [laughter] I've heard about this graphic novel fever and everyone's looking for the next graphic novel, and I'm like, really? I don't hear my phone ringing.

I was in Low for most of my adult life, making art or whatever you want to call it, and the good thing that was drilled into me was that you have to bust your ass. The same way that you work at any other job. Everything builds upon itself. By the end of ten years we were making an okay living. It wasn't because of what was new, but because of all the work we'd done over ten years. That's what I feel I'm doing in comics right now. I probably have another seven years of playing shitty dives. I'm building a body of work, and there's no easy or fun way to do that.

SPURGEON: I think you're at least oriented in a way that mitigates some of the disappointment that comes with comics.

SALLY: Because I come in disappointed? [laughs]

SPURGEON: Well, I think some of my musician friends are more cognizant of the fact that a lot of what constitutes success in art is being able to make a modest living at it. There are certain aspects of comics where the baseline expectation is reaching the success of the elite creators instead of the working ones. Syndicates aren't getting most of their 8000 submissions a year from people who hope to maybe make $31,400 after ten years of making a lot less.

SALLY: I don't talk to that many cartoonists, but I know a lot of them have that dream of just being able to do their work every day. I would love for this to be my job, that I could sit and draw comics. You can be

George Herriman. Not that I'll ever be a genius [laughs], but that this is what you do. You're not going to get super-wealthy or super-famous but the dream of being able to do your work and make a living from it. That's the dream.

*****

Sally asked for the following postscript:

I'd like it to be known that I in no way view Fantagraphics or Coconino as the equivalent of "a shitty dive." Obviously, Fantagraphics is one of the (if not the) most important comics publisher in America, and I'm truly honored as hell to be working with them.

I think my analogy still works, though, in that making the effort to see a band in a "shitty dive" is something that only someone who has an active passion about music (and that culture) would do. How, if, when or why the work makes its way out beyond that dedicated following into the mainstream is anybody's guess (and actually, most of the best shows are in shitty dives, so there's that).

The larger point I think can be made is about the realities of the market. Even though I am being published by the biggest "art comics" publisher in America (and the added fact that the work is being translated into 3 other languages under the auspices of another great publisher, which actually means the pay is a bit above "normal"...), it's still in no way anything anyone could live on, much less support a family. it's not bad or good, it's just what it is.

*****

all art from the first volume of Sammy the Mouse except inside cover to Nate Denver's book, Dead Ringer image from Jason Miles and the operating room panel from an issue of Recidivist. Photos provided by Sally.

*****

Sammy the Mouse Vol. 1, Fantagraphics, Ignatz Series, magazine-sized, 32 pages, May 2007, $7.95.

*****