Home > CR Interviews

Home > CR Interviews A Short Interview With Douglas TenNapel

posted August 11, 2007

A Short Interview With Douglas TenNapel

posted August 11, 2007

*****

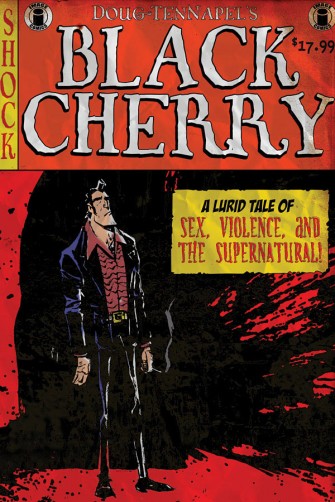

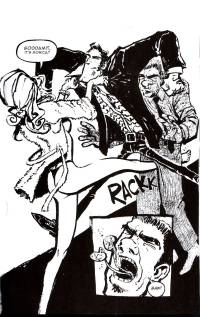

Douglas TenNapel is a potent comics maker. To my mind he's cartoonist working in the manner most reminiscent of the furious indy-comic ink throwers of the first half of the 1980s, that period in comics history when ambition and productivity were a forced marriage whether you approved of the union or not. TenNapel's latest in his recent, furious run of original graphic novels over the last half-decade is called

Black Cherry. It's an odd mix of anachronistic visuals, modern setting, ugly curse words, humor so broad Benny Hill might express disbelief a scene could be played that way, meticulously staged set pieces, straight-faced explorations of faith from a series of right angles, a dash of science fiction, a dollop of horror and a heavy amount of old-fashioned American violence. There are few comics out there like it.

One day I'd like to dig deeper into some of the issues we begin to get into here, because certainly there's much to discuss, but for this piece I wanted TenNapel's point of view in order to facilitate insight into the work. Speaking of which, I dithered while assembling the questions for this interview, coming back to them off and on over a long period of time. I'm not sure why. For his part, TenNapel was lightning quick to respond. I think that suggests something about the spontaneity with which he's creating, although it's fairly obvious in the work, too. I greatly enjoyed our discussion.

*****

TOM SPURGEON: Doug, you've been really prolific since turning to graphic novels in a more dedicated fashion a few years ago. How much of your work time is devoted to comics? Can I ask what your work day is like in general?

DOUGLAS TENNAPEL: I've learned that it's never a good time to write and draw anything. Life has a way of making that decision to write today difficult. I have "real jobs" to do, I'm neglecting my wife and four children, the house is falling apart etc. So to some degree, I have to just hit the comic at least once a year no matter what.

My life always seems flexible enough to squeeze in a graphic novel a year and that's even during some busy years. The reason is that I write and draw comics from a different place that isn't being used at all in my other life pursuits. For instance, the graphic novel is one of the few places where I have to answer to nobody... that already cuts the work time in half. These stories are also coming from a pretty deep pool in me that's pent up, untapped my whole life. When I turn that faucet on it only has one mode-- full blast. I find energy I didn't know I had to make the graphic novel.

My work day in general starts with my kids waking me at 6 AM. That means I'm writing and drawing by 7 AM. By 9 AM I'm at my peak and finishing up by noon. The rest of the day is for family, friends, "real jobs" and even then I can usually wrap up my work by 7 PM to help get the kids a bath. I've found there is no room for TV, video games, travel or non-essentials. I don't ever feel guilty for wasting time because I can't think of the last time I wasted an hour of my waking life.

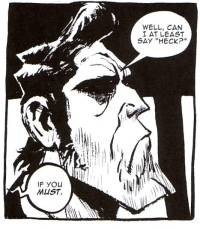

SPURGEON: You make an interesting statement right up front in your graphic novel about its use of language and nudity. Have you experienced a negative reaction to these kinds of story elements in the past?

SPURGEON: You make an interesting statement right up front in your graphic novel about its use of language and nudity. Have you experienced a negative reaction to these kinds of story elements in the past?

TENNAPEL: I've had a lot of flack for using "damn" from Conservative Christians so I new I'd get some criticism from my more conservative readers. I don't blame them at all, by the way, since I think their position is reasonable in a culture that has always pushed the envelope on making the taboo the norm. A recent fan said that he would be passing on

Black Cherry and I said, "Skip this one with my support... but check out my next book which will be for everyone."

SPURGEON: The design to Black Cherry

echoes the old EC comics. Are you a fan of EC? What do you feel your new book has in common with those comics?

TENNAPEL: I'm not so much a fan of EC... I'm more respectful of those works. They have these dark stories, usually stand-alone where they just dive into a dark place and try to shake up the reader, then get out of the story. The whole premise attracted ballsy story-telling that sacrificed care for power.

Black Cherry is a very careless story in that I really tried to get to the hard core bottom shelf of my person as quickly as possible. I also didn't care what publishers, my audience or my family might think about the story. I don't mean that I don't respect these influences, just that I thought being overly conscious of what they think would hurt

Black Cherry.

SPURGEON: Given the potential offense some might take in the material, do you feel that there are any limitations you need to place on your depiction of such characters and setting? Or to put it another way, Doug: do you really need all the jokes about gays in order to accurately portray that world?

TENNAPEL: I'm an equal-opportunity offender, and I didn't feel the need to edit out the gay jokes any more than the cussing. I did put two limitations on myself that I just couldn't stomach in the material and that's using the word "nigger" and showing genitals or the actual act of sex. It was only because I thought that doing that would be so distracting from the story that it would halt all of my readers pulling them out of the world for that moment.

In the cultural machismo world of men, gay jokes come up often. I don't know if I needed as much of it as I used, but it seemed character-appropriate in every time it happens in

Black Cherry. "Faggot" is a big word to us, but it's not a big word to the L.A. Mafia and a bunch of urban gang-bangers. There are no men actually practicing homosexual behavior in the story so I'm not making a comment on how we should treat gays any more than I'm laying down an example for how we should treat race or religion. If anything, I didn't put enough gay jokes in to accurately portray that world from what I've seen of that world.

SPURGEON: What do you feel is the artist's responsibility to draw the line? You're not showing hardcore sex, so you're obviously making some choices on what to show and what not to show. Do you feel there's any danger in presenting a world and endorsing a worldview or philosophy through what you choose to emphasize in your comic?

SPURGEON: What do you feel is the artist's responsibility to draw the line? You're not showing hardcore sex, so you're obviously making some choices on what to show and what not to show. Do you feel there's any danger in presenting a world and endorsing a worldview or philosophy through what you choose to emphasize in your comic?

TENNAPEL: I feel absolutely responsible for every word or image I put on paper. When I sign my name to something I say, "I endorse this"...but if a fictional character makes gay jokes, lies, uses drugs, mocks Catholicism, commits murder, it's not an endorsement of behavior. The story is pretty clear that all of the characters are pretty jacked up people and I hope the take-away is that these are not models for behavior. In fact, of all the bad behaviors shown in

Black Cherry I'd say that gay and racial bigoted statements rank pretty low compared to demon worship, murder, heroin use etc.

SPURGEON: Black Cherry

features this incredible array of kind of cartoony character types: a Mafioso soldier-style hood, black gangsters, priests, strippers, even creatures not of this world. Can you talk about how you went about building this setting and these people? Did the story demand this many character types? Do you start with characters or setting you want to use and assemble a story from there?

TENNAPEL: It all started with the straight up crime story of the first act. That's pretty typical stuff where a criminal deals with loyalty issues between competing bosses, etc. The same with the troubled girl, this is standard stuff in crime noir. I found a lot of Catholicism within the mafia stories, probably due to the gothic nature of those worlds as well as a tie between Italians and their faith of choice.

But after the first act I gave myself permission to twist the genre. A stolen body isn't human, the mafia has supernatural ties and once a few of those fantastic elements get into a story they jack things up pretty quickly. I didn't want the wheels to fall completely off the wagon so I forced these fantastic elements to serve the crime noir structure. I don't want to give away the ending but it is a by-the-books crime noir ending that proves the whole story was serving the genre canon, not the twists I added into it.

I'm a plot guy so I tend to not let my characters run off on too long a leash. It probably makes my characters a little stunted but it makes my plots bigger and more complicated without getting myself into story trouble. Some find the graphic novel's length a great way for characters to meander even farther down the road before they have to wrap things up but I find the long form suits bigger plots the best.

SPURGEON: While we're on the subject, what was the specific genesis of Black Cherry

?

TENNAPEL: Pulp Fiction,

The Godfather,

Miller's Crossing and

Sunset Blvd. I like what those movies have to say about humanity but I knew I couldn't pull off a straight up crime noir work. I thought it would be a fun arena to do my thing and out came

Black Cherry.

SPURGEON: One of the obvious themes to

SPURGEON: One of the obvious themes to Black Cherry

that you even explicitly acknowledge I think at one point, is that people tend to have serious spiritual concerns or thoughts on their place in the universe, no matter their station in life. Is there anything in your own life that led you to that point of view?

TENNAPEL: My biggest beef with the portrayal of Christianity in comic fiction is how it is presented as a thin world view.

Black Cherry has protagonists wrestle knee deep with the cost of sins, regret, guilt and what happens when forgiveness isn't detected by the five senses. They don't just laugh it off and say, "Ha-ha! Well, I'm done with that philosophical crisis. When's lunch?" They find the tough economy of Christian forgiveness as hard to swallow, their doubts wreck their conscience, they find their old life-styles inescapable... and appealing.

My personal life... needs to remain personal. But I don't think the regrets that keep me up at night are any different than any of my readers. I think profound guilt over past sins, even forgiven sins, are things that every person can relate to. Maybe I'm projecting and if that's the case I won't be the first author to project his idiosyncratic dilemmas into his own work. I've found that I can be flip about bad things I've said and done and then I find those things keep me up at night ten years later.

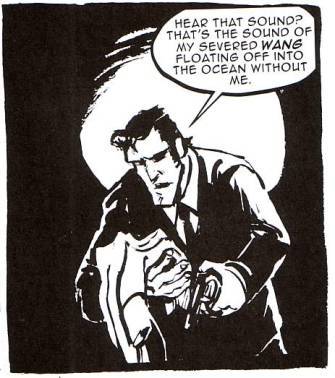

SPURGEON: There's a ton of humor on display in

SPURGEON: There's a ton of humor on display in Black Cherry

. There may be more funny moments in this new book than I can remember in any of your other works. Can you talk about your humorous influences, both in comics and in general? Do you have any particular role-models? Is there anyone you feel is extremely funny?

TENNAPEL: I love everything funny. I have the highest respect for physical actors: Keaton, Chaplin, Laurel and Hardy because it looks really hard to do. My role models are the Coen Borthers because they're so good at presenting humor while expositing a convoluted plot. Guys I think are extremely funny are Dan Harmon, Rob Schrab and the gang. They think fast and surprise their audience with just about everything they do. There's also a nervous tension with them where you

fear what they're going to do and say, like that drunk uncle that might just jump up on the Thanksgiving dinner table and pull down his pants.

It's a guilty pleasure, not humor I'm proud to enjoy, but there you go.

I agree that

BC is one of my funniest graphic novels and it's probably because of the R rating makes it easier to tell jokes at the crotch level. G rated humor is the hardest to do and the one I respect the most. R rated humor is the easiest to do and the one I respect the least.

SPURGEON: Do you believe that demons and angels play an active role in earthly matters?

SPURGEON: Do you believe that demons and angels play an active role in earthly matters?

TENNAPEL: Yes.

SPURGEON: Do you believe in life on other planets?

SPURGEON: Do you believe in life on other planets?

TENNAPEL: No.

SPURGEON: How does your belief or non-belief in these matters come to play in your using them in the comics?

TENNAPEL: It doesn't that much. I don't believe in Bigfoot but he's in my comics. Even the Christianity I present in my books is not the Christianity I believe. The Christianity I believe doesn't necessarily make for interesting graphic novels and in the end I want to weave a good story.

I don't fear using Christianity in my books and I know there are people who are trying to make that a "no-no". Almost all of the criticisms I get about using Christianity in my works come from our modern Relativist world view. They will fall into these kinds of critiques: "Who are you to judge?" "You actually think your world view applies to everyone else." "Your Christianity is fine if you keep it to yourself but don't march it out in public."

There's an implication in a philosophical world view called "Materialism" where only empirical (things we see, touch, taste...) materials are true. If I imply that non-empirical things are true and true in a sense for everyone and not just my little Christian ghetto then some are conditioned to attack. Authors like Sam Harris and Richard Dawkins are shaping pop culture to not only disregard the Christian world view, but to call it dangerous, delusional and on par with Radical Islamic terror.

Deep down inside, I work hard to completely ignore voices that can't tolerate my world view. I tolerate their world view... and tolerance is in no way endorsement. Okay, I feel like I'm really flying off the handle here. Sorry, but if you want to crack into how my world view influences my work this is where we're going to go.

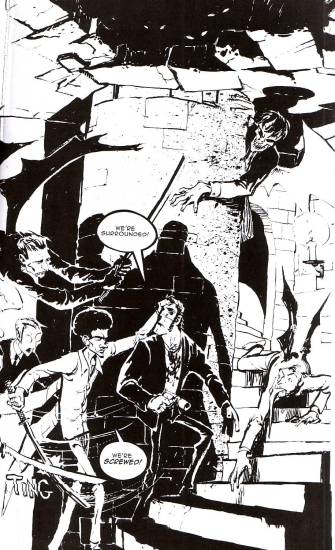

SPURGEON: How do you approach a page? Is the overall design of an individual page an important factor to you?

SPURGEON: How do you approach a page? Is the overall design of an individual page an important factor to you?

TENNAPEL: The overall design is important to me but I really stink at that part of comic art. Guys like Eisner, Mignola and Miller really know how to put a page together. They make works of art that if you squint the panels cohere into a single, powerful graphic statement. I have a really hard time with this because I really do compose at the panel level and not much higher. This makes for ugly, random or unclear full page compositions. We all have something to work on and this is one thing on my long list of things I need to get better at.

SPURGEON: In Black Cherry

, there's a lot of three-tiered pages, many that run the width of the page. How big a factor on each page is pacing the action?

TENNAPEL: I got the three panel formula from Scott Morse...and it's more a short-cut than a feature of the page. I knew I was going to need big panels because I was inking with a huge bamboo horse-hair brush. Mignola can put 16 panels on a page when drawing with a Micron pen and his pencils are super-tight. But I knew BC was going to be loose, so I geared the workspace for speed and expression over appeal and accuracy.

Pacing isn't difficult since I work form tight script break-downs and some thumb-nails. I feel like my pacing of late has been suffering and I'm not sure why. It could be that I'm forcing action into a plot instead of letting the characters breath in their particular situation. Again, this isn't my strength and I've got something to work on for the rest of my life. I'll go to digital drawing someday and that will make editing and changing panels around a piece of cake.

SPURGEON: You use a silhouette effect several times in the course of

SPURGEON: You use a silhouette effect several times in the course of Black Cherry

. Is there a certain reaction you want from the reader when you use that approach, or is it more of an intuitive act on your part. Why are those specific panels done in silhouette?

TENNAPEL: Silhouettes look like ghosts to me, you know? They character is represented by a featureless body so it turns the moment into an icon and I LOVE IT. I don't always have a reason for doing it but it always feels good to put one in when I do. I can usually decide to go silho' at the pencil stage... when all of the information can be communicated without the interior detail that panel just became a candidate.

SPURGEON: Doug, I like the way that you plot out your set pieces: like the fight with the jilted lover and her husband near the book's beginning, or Eddie swiping the body, or

SPURGEON: Doug, I like the way that you plot out your set pieces: like the fight with the jilted lover and her husband near the book's beginning, or Eddie swiping the body, or Black Cherry

's dream where Eddie pays her. Do you pay special intention in staging a special scene like a big fight, or does that just naturally flow with the rest of the narrative? Do those scenes get special consideration?

TENNAPEL: Yeah, they are meticulously choreographed... usually for clarity without sacrificing impact. In those cases you cite they were probably particularly convoluted in the script where I say, "I don't know where I am in the room" so I'll do an overhead schematic of the room, even placing furniture, doors and windows so I can block out a scene. Those tend to be more cinematic moments since I'm so influenced by composing for animation where everything is exaggerated for both drama and clarity.

SPURGEON: How do people respond to your pursuit of spiritual issues through your comics? Has any reaction ever surprised you?

TENNAPEL: No matter the response, they are always passionate. These topics cut a reader to the core and all of their offenses, defenses and deep feelings are usually hit at some level. I get two responses that really surprise me. One is by the Christian kids who read my work and tell me, "I didn't think a Christian was allowed to tell these cool stories. Now I have a new perspective on my pursuit of the arts." That's by far my most common response.

The other response I get from atheists or ex-Christians who can appreciate the work even though it doesn't agree with their world view. Some of my biggest fans are atheists. I think deep down inside, they have a soft spot for the religious culture they may have been raised with. Some appreciate the role Christianity has had on the west and don't buy into the modern paranoia of America's favorite religion.

At this point, nothing surprises me. I love to read what people think of the work and given the variety of responses, I think I'm onto something that just isn't present in other graphic novels. I didn't set out to do X or Y but I don't run from whatever story I choose to tell either.

SPURGEON: Something I think you do well is balance a kind of illustrator's approach, where your images are nice to look at, with a sense of movement and flow that's reminiscent of animation. How do you balance making an image that people want to pore over while at the same time communicating a certain amount of activity from panel to panel?

TENNAPEL: I learned how to draw comics by being an animator. Even "Silhouetting" is a foundational principle in animation. I studied design and composition most of my adult life so I have those elements working in me... at least at the panel level. I don't find a dichotomy between communicating story and making images that hold up to a long viewing. I'd say my images are better at telling story than hold up to being studied for more than a few moments. Comics as a medium means that every image only exists to tell the story. It's not an art contest and it's not my very best work by far. I know the panel is done when it does the job of telling the story, not when it impresses my art friends or even the reader.

SPURGEON: You've been an important part of Image's revival in the last few years.

SPURGEON: You've been an important part of Image's revival in the last few years.

TENNAPEL: That's funny because I've always seen Image as been an important part of my arrival in comics.

SPURGEON: Do you feel comfortable at Image? What is that company's greatest appeal to you?

TENNAPEL: I feel very comfortable at Image. Part of that comfort is their deal with me which is no deal at all. I can leave or they can quit publishing me whenever and that means we're both about making just that graphic novel and getting it out to the public. Image holds hands very well with my philosophy on most of my graphic novels. I think if I ever needed a sizable advance on a book I might part company with them for just that book and I think Image would be the first to be okay with that.

Image's greatest appeal is that they love comics. They didn't get into comics to make money on my movie deals and all of the Image gang have their own creations to work on. It's weird, because even though they are fellow comic creators they aren't in competition with me. It's not presented as a zero-sum gain where their careers are somehow threatened because [my] career goes good or bad.

SPURGEON: Do you feel a kinship with other Image creators? Which ones?

TENNAPEL: I feel a kindred spirit with Todd [McFarlane] because he's seen as a bit of a prick and he just creates his own stuff. I don't get the sense that he gets up in the morning to take a poll about what the industry thinks of him before he dives in and does his thing. I also like Erik Larsen a lot because he's like the responsible daddy-figure over there. His own comic work is mind blowing when you consider his non-comic duties at Image. I guess every comic artist has a hyphen by his job title in some way.

SPURGEON: What's next?

TENNAPEL: Flink.

*****

*

Black Cherry, Doug TenNapel, Image, soft cover, 192 pages, 1582408300, 9781582408309, July 2007, $17.99

*****