Home > News Story and Obituary Archive

Home > News Story and Obituary Archive Obituary: Ward Kimball, 1914-2002

posted August 30, 2002

Obituary: Ward Kimball, 1914-2002

posted August 30, 2002

Ward Kimball, one of the "nine old men" driving the animation division of the Walt Disney Company during its most fertile period, died on July 8 at Arcadia Methodist Hospital in southern California. He was 88 years old. According to a statement made by Disney's Buena Vista division and board member Roy Disney, Kimball died from natural causes. A one-time chief animator of Disney Studios, Kimball has become influential in both comics and animation for his refined character work and the madcap energy of his best, show-stopping movie scenes. A train enthusiast since childhood, Kimball was also one of those who adherence to that hobby helped in the formative stages of the amusement park side of the Disney entertainment empire.

Kimball was born in Minneapolis, Minnesota on March 4, 1914. He drew his first picture at age three, a train, making the artistic attempt not only a prescient display of talent but of subject matter. He eventually chose the medium over the message, and became a student at the Santa Barbara School of the Arts. Kimball submitted his portfolio to Disney in 1934 at a teacher's insistence, demanding an instant decision from his evaluator due to the fact he lacked the money to make the trip to Los Angeles again. His first solo assignment came less than a half-year later doing animation on a musician in Woodland Café, one of the studio's incredibly popular Silly Symphony series.

According to studio legend, Kimball nearly quit outright when informed by Walt Disney that his signature scene had been cut from the Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs feature. Known as the soup scene, the sequence, pulsating with energy and action, is a popular staple in its never-completed pencil animation form on programs about Disney animation and the studio's history. Kimball's own writing from that general period notes the energy with which the creative people at the studio -- including close friends such as Walt Kelly -- embraced the skills and training need to do their jobs. He did, however, note the long hours of a non-union shop.

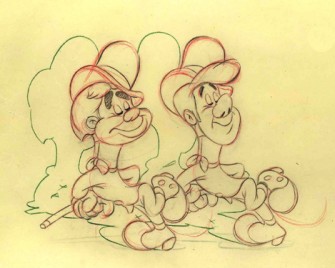

Kimball's creative contribution to the Disney's studio followed the general pattern of his first effort, albeit with more success in getting product on-screen. He gave the movie division some of its most interesting character work and mad-cap, show-stopping scenes during that great, prolific period of the 1940s and 1950s. He was responsible for Jiminy Cricket in Pinocchio -- one of the few Disney characters far more beloved than the feature from which he sprang -- as well as the crows in Dumbo and Beethoven's Pastoral Symphony in Fantasia. Jiminy Cricket was the bone tossed Kimball after the disappointment of Snow White, and Kimball in designing the character touched on a central truth of creating memorable characters for American audiences -- they'll very often believe what you tell them. "I ended up with a little man who looks like Mr Pickwick, but with no ears, no nose and no hair," Kimball later told an interviewer. "The audience accepts him as a cricket because the other characters say he is."

In addition to creating a break-out character who has since enjoyed television hosting duties and other media appearances, Kimball supervised scenes that enjoy a larger reputation than the movies around them. He directed the jaunty Tea Party in the largely forgettable Disney adaptation of Alice in Wonderland, and popped eyes of young animators and cartoonists around the world with the smoking hot final musical number in undervalued The Three Caballeros, as Donald Duck, Jose Carioca and Panchito bring down the house.

In later years, Kimball became a go-to guy for many of Disney's more innovative projects. In one protean year, Kimball directed the first Disney cartoon in 3-D, Adventures in Music: Melody, and the studio's first CinemaScope cartoon, Toot, Whistle, Plunk and Boom. The latter won an Academy Award, Kimball's first as a director and a feat he would repeat in 1969 for It's Tough to Be a Bird. A short list of Kimball's other projects at Disney includes Make Mine Music, Peter And The Wolf, Melody Time, supervising the Lucifer the Cat character from Cinderella, writing the script for Babes in Toyland, working on Peter Pan, Mary Poppins and Bedknobs And Broomsticks, and producing and directing 43 episodes of the syndicated television series The Mouse Factory. Kimball also wrote and directed a series of space-related shows for the Disneyland television shows in the 1950s that cultural historians claim paved the way for public acceptance of the space program.

Kimball also pursued projects outside of animation. In the 1964 film short Art Afterpieces, Kimball drew on advertising and art masterpieces with equal, disrespectful fervor, thus "improving" them. It later became a successful book. Outside of filmmaking entirely, he pursued his music career with the Dixieland jazz band Firehouse Five Plus Two. Kimball played trombone, and the band featured fellow Disney great Frank Thomas on piano. Originally an in-house band at the studio, the Firehouse Five Plus Two eventually made multiple television appearances and recorded a dozen albums.

Kimball was a noted train enthusiast his entire life, and after retirement in 1973 served for several years as president of the Train Collector's Association, attending conventions and making a name for himself not so much as animator but as a train lover's train lover. The first privately-owned backyard railroad in America was founded and built by Kimball in 1938 on his property in San Gabriel, California. The two steam engines and multiple cars of the Grizzly Flats Railroad ran on 500 to 900 feet of 3-foot gauge. A similar effort by Walt Disney to work with his company's machinists and company railroad fans like Kimball has long been considered an important first step into three-dimensional entertainment for the company, and photo evidence of the 1950 founding of the Lily Belle on Disney's property reveals Kimball close by, grinning.

Kimball's grandest post-retirement public appearance was on a 1978 train tour from Los Angeles to New York in celebration of Mickey Mouse's 50th birthday -- a character he once was put in charge of re-designing. But he also served as an important consultant on the long-simmering Epcot project at the Orlando amusement park, an important effort to the company, as it was completed after Disney's death and during a down period for the animation division. In 1992, he donated a portion of his railroad to the Orange Empire Railway Museum in Perris, California.

Enthusiastic and personable, Kimball's longtime employer once confessed to family members he was one of the few men Disney knew who could actually be called a genius. The seventh of the Nine Old Men to pass away, Kimball was the hidden, helpful caretaker of the Disney Empire, gracing nearly every facet of the worldwide entertainment company with his touch and carrying many a project or tough story point on the broad back of his creative talent.

Ward Kimball is survived by Betty, his wife of 66 years, two daughters and a son.