Home > News Story and Obituary Archive

Home > News Story and Obituary Archive Harvey Pekar, 1939-2010

posted July 13, 2010

Harvey Pekar, 1939-2010

posted July 13, 2010

By Tom Spurgeon

By Tom Spurgeon

"Comix are

words and

pictures...

words and pictures... you can do

anything with

words and

pictures..." -- Harvey Pekar

Harvey Pekar, a writer and critic whose comics output was dominated by mundane stories of everyday life as lived by the author in Cleveland, Ohio,

was found dead in his home early July 12 by his wife,

Joyce Brabner. An autopsy by Cuyahoga County officials will seek to reveal the exact cause of death.

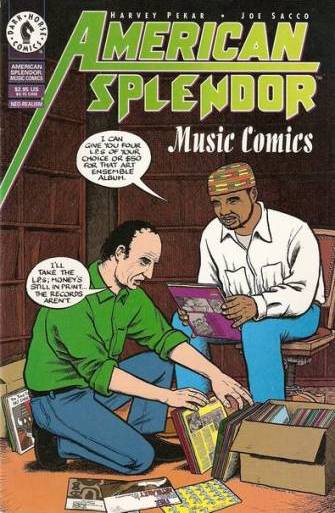

Pekar was an influential figure for multiple generations of comics creators. His initial comics as published in his own

American Splendor bridged the artistically fallow time period between the fall of the undergrounds and the rise of alternative comics. He was a key early and relatively successful self-publisher who forged a path for a number of creators whose fortunes became a single publication tied to their name and creative skill. His force of personality, quick wit and combative nature made him a formidable presence both within the comics industry, and, starting with a platform provided by

NBC's Late Night television show, the wider entertainment industry.

A 2003 film about his life and work bearing the same title of his magazine won widespread acclaim and became one of the most critically lauded comics-related movies in a decade stuffed with them. Best known for his short stories, Pekar became a surprise, key player in the literary graphic novel movement upon the 1994 release of the book-length

Our Cancer Year, in collaboration with Brabner and artist

Frank Stack. He continued to collaborate and create until the very end of his life, with several projects ongoing and multiple conversations with editors about the wave of work to come after that, some discussions taking place within days of his passing.

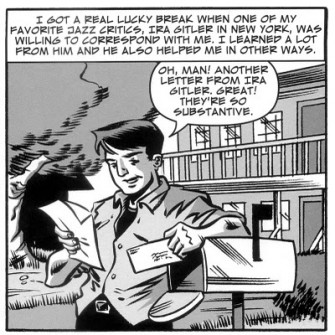

Harvey Pekar was born to Polish emigrants Saul and Dora Pekar on October 8, 1939. Harvey, his parents, and a younger brother lived above the small grocery store his parents owned and operated. His physical exploits and displayed ability to protect himself as a young man became the subject of a later, significant book project. Pekar graduated from high school in 1957 but dropped out of

Case Western Reserve University due to anxiety over a math requirement. He served in the US Navy and upon return home worked menial labor jobs before scoring a civil service job at Cleveland's Veteran Administration Hospital. He worked there, the eventual setting for many of his comics, until retirement in 2001. Pekar also began to establish himself as a writer, published nationally as a jazz critic at the age of nineteen. He would continue to write criticism through his career, for a variety of outlets, in comics, prose and through spoken word. Some would argue that the comics for which he would eventually become best known were a form of criticism as well, both depicting and commenting on the age in which he lived.

Pekar fell into comics through a friendship with cartoonist

R. Crumb, who lived in Cleveland during the early '60s working for greeting-card giant American Greetings. Pekar would in the early 1970s become inspired to write his own comics, utilizing a stick figure layout for his scripts that he would then give to artists for illustration purposes, a working method he would use throughout his career. Both Crumb and fellow underground Bob Armstrong expressed interest in potentially drawing Pekar's comics, which seems, in turn, to have provided Pekar with the drive to seek publication.

"I began corresponding with Harvey in 1972, several years prior to the debut of

American Splendor,"

Denis Kitchen told

Comics Reporter. "I still have all the correspondence, which I just quickly pulled to establish some time frames. His first pitch to me (6/72) was, 'You know any artists looking for stories? I can't draw but I write great stories, chock full of redeeming social value. Like I do stuff about how I fought my way up from Cleveland's tough East side to become a world renowned jazz critic. Just ask Crumb & up & coming Bob Armstrong & they'll tell you how deep I am.'"

Kitchen continue to correspond with the all-but-unknown writer (a one-pager with Crumb called "Crazy Ed" marked Pekar's comics debut in a 1972 issue of

People's Comics. "We had a tough time figuring out who he should collaborate with," he said. "It took a while. The first work I accepted wasn't until 1974: one with Gary Dumm ("How'd You Get Into This Bizness Ennyway?") and one with Bob Armstrong called "Don't Rain on My Parade." They appeared, respectively, in

Bizarre Sex #4 and

Snarf #6. I also used him in my Marvel experiment,

Comix Book,

Bop and a later

Snarf. Pekar also worked with Willy Murphy during this period and, through eventual long-time collaborator Dumm, Greg Budgett. Pekar's relationship with Kitchen would extend into the early 1980s. By that time, Pekar had found what would become his finest vehicle.

Pekar published the first issue of

American Splendor in 1976. The mid-1970s were a transitional time for comics. Both the Marvel superhero comic revolution of the 1960s and the underground comix movement of the late '60s and early '70s had reached diminishing returns, at the very least in relation to their initial, respective bursts of energy. Each industry was also facing massive distribution difficulties through the decline of the newsstand as a place for cheaper periodicals and the disruption by law of the once underground comix-friendly headshop. Publishing on his own didn't just secure for Pekar unfettered access to the comics page, he could enjoy a slightly greater profit margin from individual issues as well as control print runs in a way they wouldn't rapidly exceed actual demand. Pekar stated in 1993 that he published 10,000 copies of each issue of

American Splendor selling approximately 75 percent of each print run in its first year.

With stories mostly free of sex and violence and not all interested in the general breaking of taboos for the sake of seeing them broken, Pekar's comics were also a safer bet than many non-mainstream comics of its era for early comic book shops, many of whom in the first half of the 1980s operated under an ethos of carrying as many comics being published as possible. Most comic shops may have not taken a chance with Pekar's work, but some that did ended up doing very well with the offbeat magazine. Fellow Clevelander

Tony Isabella told

CR that Pekar had a sizable local audience through the emerging Direct Market. "By the time the third issue came out, I had bought a comics store in the heart of downtown Cleveland. I ordered a minimum of 50 copies of each new issue, which I soon raised to an even hundred. I kept all the back issues in stock as well. Add up the new sales and the back issue sales and

American Splendor was selling as well as

X-Men for me."

Pekar was also able to hand-sell his comics directly to fans at places like the Chicago Comicon. While even taken together these various sales avenues were never enough to take Pekar away from his day job, in the hardscrabble world of non-traditional comic books Pekar was able to establish a reputation as a fighter and survivor. Fans felt they could count on

American Splendor and anticipated new issues no matter how they might attain them. He also became, unlike many of the underground cartoonists, a member of the North American comics professional community -- attending many of the same shows, having his comics racked in the same shops, vying for attention from the same fan press. Larry Marder remembers a Harvey Pekar who was light on his feet. "Back in the old days of the Chicago Comicon, nighttime dances were fairly common events with DJs and sometimes live bands. Most pros, myself included, were too futzy to get on the dance floor. But not Harvey. That cat had some serious moves. All in a '60s sort of way but I can close my eyes and see Harvey sorta low to the ground, Joyce [Brabner] across from him, Harvey's skinny arms and legs undulating in a perfect groove with the beat as if he were actually part of the music. I knew that Harvey's brain was filled to the brim with knowledge as a lifelong collector and writer about music. But until that moment I didn't now just how in tune his body was with it, too."

Perhaps most importantly, through the first several issues of

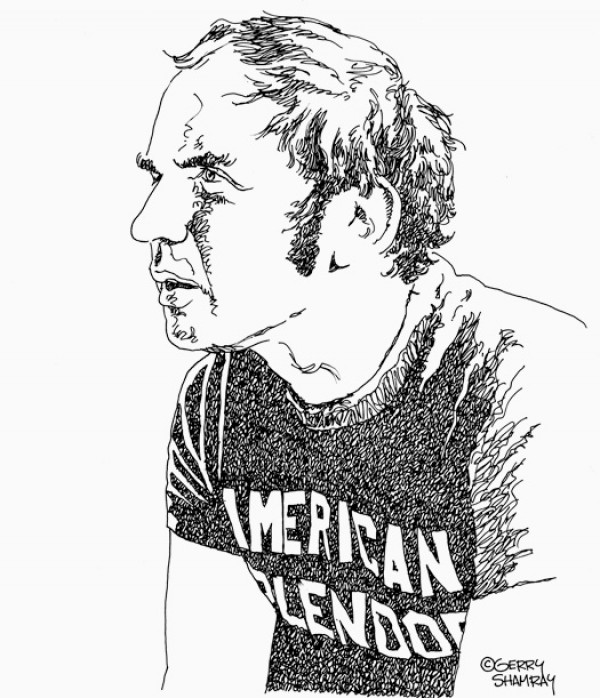

American Splendor Pekar forged relationships with a cadre of artists, including specific relationships that would extend through the bulk of his career. Most of the artists reacted positively to the experience of collaborating with Pekar. "It was a true joy for me to work with him," early

American Splendor artist Gerry Shamray told

Comics Reporter "I was flattered that he trusted me with his stories and was open to any suggestions I made on how to illustrate them. I will always remember him with fondness that he treated me as an equal in the creative process. He actually made me feel like a real artist and I never wanted to disappoint him."

American Splendor

American Splendor would publish roughly once a year during its initial run. Pekar's attention to distinct personalities and the elements of life as lived that he once termed the other ninety-five percent of human experience that doesn't get covered in media and art garnered him significant attention from fellow professionals and astute comics readers as the issues continued to come out. "For me the most important thing in the early '80s was that there was so little one could point to in the 'ComicsForGrownups' world we hoped for and dreamed of," Neil Gaiman told

Comics Reporter.

American Splendor was one of those books one discovered and then gave to friends going 'See? Like this.' I picked it up because I was a Robert Crumb fan, and then stayed because I loved the little slices of life. So perfectly observed and expressed."

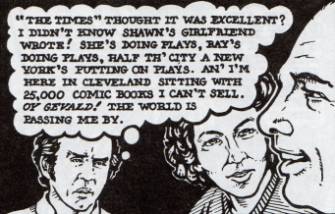

"Quotidian tales of moving furniture, collecting records, small talk during work breaks, sneaking into movie theaters: nothing ever seems to really happen," critic Tim Hodler describes

American Splendor to

CR. "None of it should work." Hodler sees a key to understanding much of Pekar's

American Splendor work in terms of the way the writer deals with the importance of unique and idiosyncratic voice. "In 'Grubstreet, U.S.A.,' [

American Splendor #6, 1983] one of dozens of stories Harvey Pekar wrote about the struggles of the writing life, Harvey -- somehow it seems wrong to call him Pekar -- reflects on a showing of

My Dinner with Andre: 'That was a good movie. I c'n see how we relate to each other's work. We both like to do things about people talking.' Like a lot of Pekar's criticism, and many of his comics are works of criticism, disguised as stories, this at first seems a bluntly obvious observation, and simple to the point of dullness. And yet, also like much of Pekar's criticism, it points out something too easily forgotten:

American Splendor, above all else, was about talk, and preserved the voices -- often in expertly rendered, Twain-esque dialect -- of people too often overlooked by artists -- layabouts, janitors, greasers, Nam vets, waitresses, jazz freaks, grad students -- and through them made poetry out of even the most mundane encounters."

For critic

Robert Boyd, this attention to language arose from a personal quality of Pekar's that served him extremely well as a comics writer. "Pekar was a really, really good listener. He's in all his stories, but much of the time, the stories are about other people. Sometimes they are stories that other people tell him, but often they are things he has witnessed and maybe played a small role in--but that primarily deal with other people. So he really isn't narcissistic. On the contrary, he is constantly observing and importantly, listening. He is trying to get the words just right." Boyd places Pekar on a continuity for comics that includes several great strips of the newspaper's 20th Century heyday. "Pekar seems to have realized that the undergrounds equal total freedom, but undergrounds were full of unrealized potential," Boyd told

CR. "It seems a cliche to say it, but the notion that a comic could be about everyday life was a forgotten fact when Pekar started doing them. There were still some newspaper strips mining this territory, but the golden age of

Gasoline Alley or

The Bungle Family was forgotten." For Boyd, the class-conscious quality of Pekar's stories, their focus on details of is life, distinguished them from much of what had come before. "His concept of doing realistic short stories and vignettes was a radical move. Basing them on episodes from his own life was unheard of. There was

Binky Brown, but I think it was really a different kettle of fish. And, outside of

Spain, I can't think of a writer with as much class consciousness as Pekar. A key story -- and I am going from memory -- in this regard is Working Man's Nightmare. Pekar is dreaming, and in his dream, he can't remember what his job is. The importance of that paycheck from the VA pops up over and over, as well as his keen sense of being working class when comparing himself to some of his bourgeois colleagues in so many of his stories."

The cartoonist Seth was another reader that felt deeply about the early

American Splendor issues, and cites Pekar's decision to depict everyday life and his success in doing so as key. "In time I came to see that Harvey was transmitting the texture of real living experience in a way that no one had done in the comics medium before this time -- not Crumb, not Lynda Barry... not even Justin Green," he told

CR. "It wasn't just that Harvey was focusing on the mundane or the folksy. That would be much easier than what he actually did. No, Harvey managed to get down on paper much of the feeling we have of actually being alive in a day to day manner. I think he did this best in those early years--those first ten years (or so) of

American Splendor --when a lot of his work dealt with loneliness. For comic books this kind of work was a genuine revelation."

Pekar's life changed dramatically in the 1980s, even as issues of

American Splendor continued to be released in almost clockwork fashion. He met his third wife, Joyce Brabner, in 1983 after she wrote Pekar asking after an issue of

American Splendor. They were married soon after they began dating, and Joyce became a presence in Pekar's comics in the 10th self-published issue of the magazine. She can be seen staring balefully at the dishwashing-challenged Pekar as the cover's text mirrors old-time romance comics in its breathless worry over the fate of their union. Brabner would become a recurring presence in any and all stories that dealt with Pekar's current life, and they enjoyed a reputation as one of comics' couples most fiercely protective of one another and each other's work. It also in some ways changed the tenor of his work, making Pekar less lonely and isolated, and taking away an element of his autobiography whereby the examination of his life's details to some readers seemed to touch on the subject of his bottom-line worthiness for domestic happiness.

Two collections of

American Splendor work came out from Doubleday in 1986 and 1987, placing Pekar squarely into the fight for wider cultural and literary acceptance for comics, although at this time the movement was perhaps based more on a smattering of noteworthy works like Pekar's rather than a rising tide. Although the exact dates remain unknown to me, I believe it's the publication of the first Doubleday volume that preceded Pekar's first appearance on the popular

Late Night program hosted by David Letterman -- I think it's in the host's hands at the top of a pile of other comic books when Pekar is introduced. More important than the exact date of that appearance is that Pekar became a popular and somewhat controversial guest during that show's most potent run as a pop culture powerhouse. His quick wit and the general intensity of his personality helped satisfy Letterman's penchant for unpredictable television. The appearances apparently helped Pekar sell more books, and generally raised his profile. Host and guest would later clash over the criticism Pekar wished to foist upon NBC owner General Electric in perhaps his most famous guest shot, criticism which he then turned on the host when frustrated in his attempts. Despite the impression sometimes left that this was Pekar's final TV appearance, Letterman and Pekar had enjoyed enough of a rapprochement that he later appeared on Letterman's CBS program.

In the midst of these television appearances, producing more issues of

American Splendor, and of course working his day job, Pekar wrote an intermittent column and some reviews for

The Comics Journal in the second half of the 1980s and into the very early1990s. He used the platform to call attention to comics work he felt noteworthy and generally advocating for the medium's untapped potential. His short run of articles was book-ended by two major interviews in 1985 and in 1993, the second showing a writer solicitous towards the struggles of fellow comics creators and praising the work of creators doing work somewhat close to his own. In 1989 Pekar was a name-in-title subject of one of the new breed of book-length academic study of comics through the prism of popular culture, Joseph Witek's

Comic Books As History: The Narrative Art Of Jack Jackson, Art Spiegelman and Harvey Pekar from the University Press of Mississippi.

The 1980s early 1990s yielded three noteworthy theatrical adaptations of Pekar's work, a tribute to the memorable character of Harvey Pekar that had been created in the pages of the comic and Pekar's attention to unique quirks of dialogue and interpersonal relationships. The first was a small production in Lancaster, Pennsylvania in 1985. The second was an adaptation by the writer Lloyd Rose for staging in Washington, D.C. The third was a year-long staging of an adaptation by Vince Waldron that ran in Los Angeles that featured comedic and voice actor Dan Castellaneta as Pekar. The last of those garnered some significant media attention at the time;

a memorial running yesterday on the LA Times web site from Victoria Looseleaf indicates that the show may have had an earlier, more modest run and that Pekar was not all the way pleased with the results. Pekar was also at one time reported to have been writing a theatrical version of his comics.

In 1990,

American Splendor ended its remarkable self-publishing run, Pekar's greatest contribution to the history of the medium. A continuation of the publication's numbering ran into issues published with Tundra (#16) and then Dark Horse (#17), but most fans see those as addenda to one of the great comics series. Pekar's impact upon comics saw any number of autobiographical cartoonists making comics while citing

American Splendor as a primary influence.

"There's no question that Harvey Pekar set the tone for confessional comics, for good or ill, in that he established that there was no experience too ordinary or too mundane to be the subject for a comic strip," critic Robert Fiore told

CR. "Whenever you see an unfiltered verite comic strip about everyday life with no clear narrative form imposed upon it, that comes from Pekar. In a sense it's a reaction to the idea that comics were naturally a form for outlandish fantasy." For Fiore,

American Splendor had an influence not just on autobiographical comics in the 1990s but on the general alternative comics movement of the previous decade that would eventually flower into today's art comics. "The most important effect of Pekar's work was in breaking down the reality wall, and I think he was instrumental in that. If you'll remember the first of the second generation art comics you'll see an assumption that comics had to be sugar coated with some sort of genre trappings. See for instance the early

Love & Rockets with BEM and the Mechanics stories, or the private eye trappings of

Lloyd Llewellyn. You see a gradual process of cartoonists realizing that these trappings were unnecessary, that you could get away with naturalistic comics about real life. I think the example of

American Splendor had a large part in emboldening cartoonists to do that. Recall that this period in the late 1980s was also the time when Pekar was having his David Letterman reluctant celebrity period, which I think sent the message that grown up material could get you notice in the larger world. I don't know if you'd have a book like

Fun Home if Harvey Pekar hadn't blazed that trail first."

One cartoonist who felt a more direct influence was Pat Moriarity, whose 1990s series

Big Mouth went so far as to reference

American Splendor conceptually by flipping the premise and having Moriarity draw stories presented to him by collaborative writers. One of those writers was Pekar. "Harvey Pekar wrote the first story of my first comic book and helped me get started as a cartoonist, and for that I'll be eternally grateful." Moriarity told

CR. Like many of the collaborators who made some of their earliest comics with Pekar, Moriarity was appreciative of the opportunity that working with the writer provided. "He saw something in me that no one else did, considering that I had hardly been published anywhere at the time… Harvey Pekar sported a gruff exterior that masked a kind and generous soul."

In 1990, Pekar was diagnosed with lymphatic cancer. The harrowing course of treatment that followed, set against the backdrop of Brabner's growing involvement with international political activism, became the subject of

Our Cancer Year. That stand-alone graphic novel from

Four Walls, Eight Windows -- with whom Pekar also published another anthology and would later release a collection of his work with Robert Crumb -- was one of several book-length graphic novels to appear in and around the calendar year 1994. As much as any book of that era,

Our Cancer Year was not only a formidable work on its own but spoke to the promise of the North American comics industry that they might one day be able to sustain that kind of significant, serious comics output season to season. Frank Stack's artwork, which at times turned Pekar's pain into a kind of rapturous dance of lines across the page, proved to be an intriguing match for Pekar and Brabner's straitlaced, matter-of-fact tone, suggesting the feverish nature of a long-time malady as well as ably depicting the physical changes felt by the writer. Neil Gaiman: "I think

Our Cancer Year is one of the Big Important Graphic Novels. It's heartbreaking and optimistic and so remarkably life-affirmingly human."

In 1998, Pekar and Brabner became the legal guardians for nine-year old Danielle Batone, making the couple a more traditional family unit and putting that much more pressure on the near-retirement writer to continue to get work and provide for the things needed by a child they were now raising as their own. The changing market for alternative comic books during the 1990s period of distributor upheaval and a subsequent market reset saw publisher Dark Horse -- as safe a haven as any as far as those things were measured -- pursue a strategy of single-issue, one-shot comic book publications featuring the

American Splendor name. Among his best collaborative partnerships during that time were those with two cartoonists whose own comics were informed by Pekar's general political awareness and his approach to a protagonist marching through landscape: Joe Sacco and Josh Neufeld. Another collaborator from this period was Jim Woodring, who praised the writer in a note to

CR. "He was very easy to work with; he sent these layouts with all the dialog and stick figures... stick figures like a child might draw, totally devoid of sophistication. I kept one and cherish it." Pekar never lost his personal touch with his artistic collaborators. "He seemed to like the results," said Woodring, "made me feel good about my work."

The partnership with Dark Horse was sought out by Pekar. "In 1992, Harvey called me up, completely out of the blue, and asked me if I'd be his editor," Diana Schutz told

CR. "We didn't know each other very well at the time, but Harvey knew I liked his work. I think I flew into Mike Richardson's office to give him the news, and so Dark Horse published fifteen issues of American Splendor over the next ten years." Like many of Pekar's collaborators and editors, Schutz became quite fond of the writer over the course of their working relationship, and considered him a friend. "He'd always painted such an unglamorous picture of himself in his comics that I was surprised to discover just how gentle a person Harvey really was. Which is not to say that he

wasn't stubborn and opinionated, because he could be both. And he certainly didn't brook any bullshit. But it was that gentle core that allowed him to appreciate the small, honest moments of everyday living and to write about human frailties and foibles with a generosity of spirit that is uncommon -- and undervalued."

The 2003 film adaptation of his life and comics,

American Splendor won the Grand Jury Prize for dramatic films at that year's Sundance Film Festival, and became one of the best-reviewed films of that year. It mixed documentary footage of Pekar with a dramatic portrayal of the author by the actor

Paul Giamatti and helped boost Pekar's public profile even further. It won the Writers Guild of America honor for best adapted screenplay, and lost a similar award for which it was nominated at that year's Academy Awards. Some might note the irony of the film losing that award to the well-regarded adaptation of JRR Tolkien's

Lord Of The Rings: The Return Of The King, the kind of fantasy that came from a very different creative heritage than Pekar's life work. The film

American Splendor remains perhaps the most uniquely structured and highly regarded films based on a comic book series in the still-current decade-plus long trend of such movies, and its greatest achievement may be in that it serves as a solid recommendation for those wishing a Harvey Pekar primer.

Pekar seemed to pursue as many film-related possibilities as were presented to him, including on-line journal writing -- Pekar had been and continues to be cited as a kind of proto-blogger, achieving on the comics page what some people writing blogs pursued on-line, although it's not a description that flatters the breadth and depth of his creative output -- which was suspended when the money ran out. A collection of the Dark Horse comics

Unsung Heroes appeared the same year the movie came out, as did a more general book collection from Random House featuring a movie-related cover and a comic from the DVD packaging of the film called

My Movie Year a landscape-formatted comic that was one of the rare Pekar efforts using a different page structure.

The last several years of Pekar's life saw him embrace a wide variety of projects, both under the

American Splendor umbrella and without, some engaging social justice issues with which the writer had always been interested. One publishing home was DC Comics and its various imprints. 2005's

The Quitter, a ruminative story about Pekar's younger years drawn with matching vitality by Dean Haspiel, marked Pekar's return to the full-length bookstore-ready comics work that he had established as a market presence a decade earlier with

Our Cancer Year. The market had changed since then, and the work was greeted with the flurry of press interested granted any popular prose author's new book. As was the case to varying degrees with a lot of Pekar's later work, artist Haspiel cites the assignment as having reestablished his own career in comics. Two short runs of

American Splendor comic books followed, with a mix of collaborators old and new, including a hefty number of alternative comics stalwarts and mainstream comics stylists in DC's sphere of influence:

Darwyn Cooke,

Ty Templeton,

Rick Geary,

Richard Corben,

David Lapham and

Gilbert Hernandez among them. The second run was even subtitled "Season Two," a nod to the short bursts of mini-series model that had come to dominate North American comics publishing. The two runs of DC comics were collected as

Another Day and

Another Dollar, respectively.

The last part of the previous decade saw Pekar take more opportunities to work on comics outside of the

American Splendor banner:

Students For A Democratic Society: A Graphic History (2008),

The Beats (2009) and

Studs Terkel's Working: A Graphic Adaptation (2009) were noteworthy titles released during the last few years. "If there was a drift in later Pekar, it was toward social history and away from his personal story -- note that Crumb left personal history to go in a different direction," editor and Pekar collaborator

Paul Buhle told

CR. "Harvey was eager to embrace all sorts of things that were not new to him, as a personal autodidact learner, but new in terms of him scripting. I collaborated by making things possible, I guess. Even when he was -- in my view -- mistaken on some particular, he had his own opinions, carefully developed."

Hill & Wang Editor Thomas Lebien told

CR that in editing Pekar during his later years he expected to encounter the irascible personality but never did, saying that any back and forth was practical in nature and focused on making the book better. "Harvey Pekar was smart and I learned to treasure how intelligent he was. It came across in his writing. He would come up with an idea, you'd toss it back to him with comments, and within a week he'd have surrounded himself with stacks of books on the subject, learned what he didn't know already, and start reading his revised script to you. That was the joy and pain of editing Harvey. You'd say, 'I think you need to go into that in greater detail,' and in a couple of days he'd have done it, but he'd want to read the revision out loud to you. As hard as it was to edit his handwriting, editing his reading voice was harder."

Another late-period collaborator,

Ed Piskor, describes a man he says he loved to make laugh who remained intensely interested in how his work was received. "Something others might find interesting, which I found fascinating, was that he really,

really, cared about what reviewers had to say about his books. After years of reading his comics I guess I imagined that he was nonchalant about how he was perceived. With the books that we collaborated on, he would either go to the library to check out what people had to say about our work, or (since he didn't know how to work a computer), he would call me up and I'd find a stack of reviews online and read them to him over the phone. Sometimes he would start getting loud as he defended what we did, like I was the guy who wrote the review. He would never let any of them go to his head if they were overly nice."

Despite a vigorous appearance for a man in his sixties and a vegetarian diet, Pekar was not free of health problems in his later years. He was diagnosed with prostate cancer, and was a sufferer of various maladies such as high blood pressure and asthma, much of which became grist for his later comics stories. In

a post for the Los Angeles Times Hero Complex blog published late on July 12, collaborator Haspiel cited Pekar's health problems as a motivation for his making art, stretching back to his parents suffering from Alzheimer's and fears that would be his own fate.

The discovery of a local Cleveland artist named

Tara Seibel led Pekar to create work with her that was then published on-line; this in turn led to an ambitious suite of web comics called "

The Pekar Project," edited by Jeff Newelt in conjuction with comics-savvy

Smith Magazine. Pekar was provided with a rotating series of regular artists and encouraged to make comics for the Internet. Once again, Pekar was working with people that were largely new to comics, a role that collaborator Joseph Remnant suggests he enjoyed. "I think he got a kick out of helping younger artists, perhaps as his way of paying forward what people like Crumb did to help him out when he was first starting out," he said to

CR. Remnant described Pekar as a no-bullshit personality frequently doing comics in his head, and as a supportive collaborative partner. "I think if he thought you were good enough for him to use as an illustrator in the first place, then he already trusted that you would make good visual decisions that were appropriate for the story. And he did seem to become even more comfortable with me as an illustrator over time. I remember one of the first stories that I did for him, he was very concerned that I get the right subtlety of the facial expressions in a story that was essentially two people talking. I think I nailed that story pretty well and after that we didn't really have discussions like that anymore."

In his final years, Pekar began to be appreciated for the model he provided younger creative people of a working writer and creator. During his a 2007 appearance on the Travel Channel television show

No Reservations, Pekar was lauded by host Anthony Bourdain as an artistic embodiment of Cleveland whose work, he was certain, would be read a hundred years in the future. In Cleveland, Pekar was considered a hometown figure of renown for years, a role that deepened in poignancy as in the 2000s that Midwestern city and so many like it suffered yet another debilitating period of economic misfortune. Pittsburgh-based cartoonist and critic

Frank Santoro told

CR that Pekar's regional identity came through to him as a fellow artist. "I will say that as a 'rustbelt' guy, Pekar was able to communicate directly to me and the values I grew up with. His dedication and responsibility to his work. And to treat it as work, not as fancy or as divine gift. Work. You do comics? Great, well, what's your real job? To me, that is the attitude in a rustbelt town. So Harvey was able to articulate what it was like to grow up with a certain set of values and mores and how to continue to live with them as opposed to freeing oneself from them which is what most get to do when they leave the rustbelt for the big city. He articulates the difficult position of the blue collar artist. I wept during the movie when they had that party for him at the end."

Harvey Pekar won an American Book Award in 1987 for the first Doubleday anthology, and shared a Harvey Award with Brabner and Stack in 1995 for

Our Cancer Year. The first ten issues of the self-published

American Splendor were named

en masse to

The Comics Journal's Top 100 Comics Of The 20th Century, Pekar joining Harvey Kurtzman, Neil Gaiman and Alan Moore on the short list of comics writers cited as the driving creator on their recognized works, and with Spain Rodriguez as one of only a few autobiographical comics-makers. Pekar's obituary ran on the front page of July 13's

Cleveland Plain-Dealer, his name and comic were both trending topics on the micro-blogging site Twitter on the day of his passing, and tributes on-line numbered in high hundreds hours after news of his death was released. It was a display off affection and respect that several people told

CR Pekar would have enjoyed immensely.

Seth eulogized the writer as a key figure in comics history. "The underground cartoonists were a generation -- a group of artists who knocked down the walls between art and commerce, shattering the traditional shape and meaning of a comic book. Later, the 'alternative' cartoonists came along -- or whatever you wish to call my generation of cartoonists -- who wanted to produce comics as a legitimate art medium. But in-between these two generations there was Harvey. A generation of one. Probably the first person who wanted to use the comics medium

seriously as a writer. Certainly the first person to toss every genre element out the window and try to capture something of the

genuine experience of living: not just some technique of real life glossed onto a story -- not satire, or sick humour or everyday melodrama -- but the

genuine desire to transmit from one person to another just what life feels like. That's the highest goal of art in my mind… I still think Harvey was right: it's getting at that quality of real experience that counts. His work was an enormously influential turning point in the history of the medium. It was a terrible shock to hear he was gone. I can only suspect that the impact and influence of his work will only grow in the decades to come."

Cartoonist Joe Sacco placed his longtime collaborator in the company of comics royalty. "It helped that he couldn't draw, that he approached the medium as an outsider, as a voracious reader of prose," Sacco wrote

CR. "He recognized that the medium had the potential to examine the human condition directly, and he threw himself into proving it and getting others to believe it. The best of his stories about day-to-day life -- about his loves, his obsessions, his work, his hobbies, his neuroses, his illness, his successes, his failures -- were powerful examples of what comics could be. Crumb, Griffith, Spiegelman and others also were pivotal in preparing the ground for the rest of us, but Harvey was an essential component in that underground mix; it is hard to imagine what comics would look like today without his ground-breaking, autobiographical explorations."

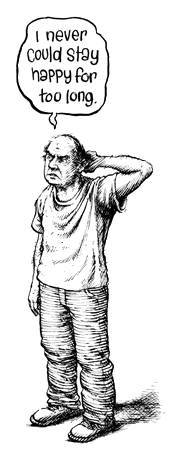

Harvey Pekar's long career was one of professional accomplishment and occasional personal frustration. "You also get a sense in his stories of his horribly conflicted feelings that he didn't just go all in and become a full-time writer," said Robert Boyd. Added Diana Schutz: "Harvey always believed in the potential of comics as literature and never understood why the market continued to produce and promote pulp fiction. I don't understand why his comics didn't make him a lot more money -- and he didn't understand that either. He was a guy ahead of his time, and I wish I could have done more for him." Alison Bechdel, speaking for a generation of readers, described the virtues of his comics in simple, straight-forward terms. "I discovered

AS in college, and loved how it wasn't really 'about' anything. I don't think I appreciated at the time that in its anti-heroism, its anti-drama, it was very much about something. The beauty of Harvey's work was his compassion for the alienated schlub in all of us, and of course, sadly for Harvey, his utter authenticity. His pain was all too genuine, and I'm sorry he had to carry it around so long."

"I feel like Harvey can't die," cartoonist

Phoebe Gloeckner wrote

CR. "Harvey and Joyce once visited my house on Hallowe'en. While I was out trick-or-treating with my kids, Harvey sat on the porch and gave out candy... there were other people at the house -- a few of my friends -- all I remember is that everybody loved Harvey, whether they knew his work or not. He seemed so happy, sitting on the porch swing in the near-dark, laughing and talking and handing out candy. He was incredibly generous and kind."

Cleveland's Harvey Pekar, the writer who changed comics with his personality and his pen, was 70 years old. He is survived by Joyce Brabner and Danielle Pekar, is likely survived by at least one former wife and may or may not be survived by a younger brother.