Home > News Story and Obituary Archive

Home > News Story and Obituary Archive Dylan Williams, 1970-2011

posted January 1, 2012

Dylan Williams, 1970-2011

posted January 1, 2012

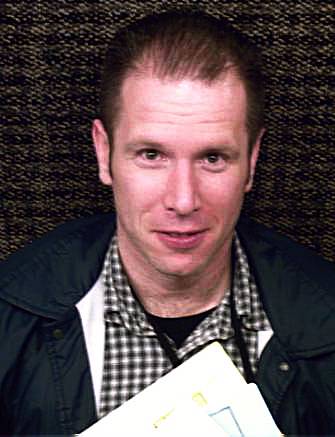

The publisher, cartoonist and comics historian Dylan Williams, best known for his successful small press publishing house and distribution company

Sparkplug Comic Books,

died on September 10, 2011 of complications due to cancer. He was 41 years old.

Dylan Williams was born in Berkeley in August, 1970. He split time during his childhood between northern California and India, spending several years of his young life in both places. According to testimony by Williams' friends, he lived primarily in a single-parent household with his mother, Joanna, an Asian Art historian and UC Berkeley professor, since retired. In

a 2008 interview with Joe Biel, Williams described being a fan of both metal and punk music, and creating his initial comics with skater friends. Williams received little to no formal training as an artist. He dropped out of

California College Of Arts And Crafts in Oakland after a brief enrollment in part, according to his longtime friend

Landry Walker, "due to disgust with the school's negative attitude towards comics."

Williams began work at the legendary comic book retailer

Comic Relief in 1992, moving between the San Francisco and Berkeley locations. He remained there until February 1996. Fellow Comic Relief veteran

Branwyn Bigglestone told

CR, "I remember Dylan being pretty shy, but usually with a smile on his face. I always felt like his ability to be entertained and impressed by the world hadn't been smushed the way it had been for so many of us jaded punk rock kids from back then. That's a special thing." The cartoonist and musician

Zak Sally, who met Williams during this period, described him as a popular, well-liked employee.

The artist

Gabby Gamboa, a longtime personal friend of the deceased, put great emphasis on the younger Williams as "incredibly self-educated, so curious about the world. He always bristled against institutionalized learning, but he could not stop following his intellectual curiosity. He would obsessively read and research about everything that interested him, comics and illustration obviously, but also film theory, history, etc." Gamboa cited his mother as a source for Williams' passion for continuing, self-directed education.

One benefit for cartoonists, comics fans and cultural historians of Williams' active curiosity from childhood through his passing was his work in comics scholarship and advocacy for forgotten or under-appreciated artists. He formally published a few articles -- his most consistent outlet was probably the short-lived magazine

Destroy All Comics -- and was singularly effective as a hands-on proselytizer, directly communicating his likes and dislikes to fellow comics fans and other cartoonists. Author and publisher Dan Nadel

cited Williams' endorsement as the primary reason for the inclusion of

Harry G. Peter in his book

Art In Time. Cartoonist Tom Devlin recalled

in a short essay at Drawn and Quarterly's blog his being directly challenged in his assessments by Williams, presented with work that Williams believe ran counter to Devlin's appraisal and asked to read and reconsider. Williams also created one of the best artist-focused web sites on-line,

The Life And Art Of Mort Meskin.

In his recently published remembrance of Williams

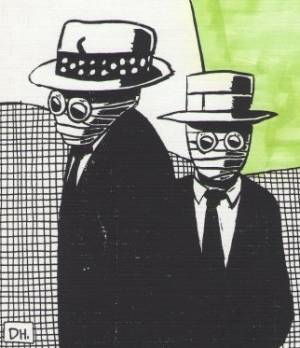

In his recently published remembrance of Williams, Sally recalled the most extravagant fruits of his friend's devotion to certain cartoonists: full 'zines of works from favorite Williams cartoonists like

Meskin,

Alex Toth,

Dick Briefer and

Bernard Krigstein (a cover for one of the Kurtzman issues is shown here) that Williams made in part due to his access to expensive original comics and archival editions on the shelves of Comic Relief. The idea was to put work made obscure by the shifting sands of history or the profit margins of archival collectors into the hands of comics fans at a cheap price. Sally wrote of Williams' motivations thusly: "Dylan did not do this because everyone would say, 'Wow, how ballsy.' It's because he thought it was bullshit that no one got to see this work. Because it was great work, important work. He didn't want credit for it, didn't want to be

seen as the guy who did that, he just did it because it needed doing."

After a brief flirtation with trying to do superhero comics, Williams had settle into a decided alternative/arts school of comics making. Williams was a founding member of the influential

Puppy Toss comics collective. Puppy Toss formed in early 1992. Founding members were Williams, Landry Walker, Scott Hsu-Storaker, K. Capelli and Chris Hatfield. Later members included Gabby Gamboa,

Ben Catmull and Eric Jones. Most of those involved had some connection to one of the Comic Relief locations. Sharing an office space -- including the still early '90s comics publishing house rarity a computer -- and working shows together, Puppy Toss may have been best known for its anthology

Skim Lizard, which published in both mini-comic and standard comic iterations. The collective also shepherded comics by individual members, such as Williams' own mini-comic

Horse. Puppy Toss was a bright spot in what many consider a mostly fallow period in comics publishing -- the business-wracked mid-1990s -- and signaled a move towards a collectivist ethos in comics making that remains in evidence today. It also directly inspired and/or guided other, similar distributors, such as Marc Arsenault's

Wow Cool enterprise. Arsenault recalled to

CR sitting in on Puppy Toss meetings and even using their computer to make his company's initial advertisements.

Walker describes Williams' involvement during the collective's initial days in terms of "directing the overall look and feel of the company, with a passionate focus on the expansion of using Puppy Toss and a distribution hub for other small press creators." The cartoonist

Steve Lafler, then an established veteran in his mid-thirties, told

CR that he sought out Puppy Toss and later wrote a piece about them for a local arts publication after seeing and being impressed by some of their comics. "Their

espirit de corps, work ethic, love of the medium, and dedication to the cooperative model -- all this stuff was a real breath of fresh air, and a major wave of fresh blood into the Bay Area scene. A lot of talent there! They were organized, had a cool catalog, a giant mailing list. [The co-op model] seemed to work for them; it really looked like everyone was willing to take responsibility for the whole deal, and it looked like they were democratic about it too."

Although several dates are given in on-line materials about Puppy Toss' closure, and some cartoonists left earlier than others, a pair of members suggested to

CR that 1995 could serve as an agreed-upon ending point.

Williams moved to Olympia, Washington in 1997 with his girlfriend Emily Nilsson. The two moved to Portland the next year, and quickly settled into a city that would in a few years' time be recognized as a potential comics-making capital of North America. The couple was married in September 2010, in a ceremony performed by their friend

Tim Goodyear.

Williams continued cartooning during the Olympia-to-Portland period, creating the initial issues of his series

Reporter, a true crime comic called

The Crime Clinic (with

Slave Labor), and a recurring strip feature called "

Hey, Grandpa!"

It was in Portland that Williams began what many consider his life's work: Sparkplug Comic Books. Cited by some as the first Sparkplug project (a copy of

Reporter: Little Black claims that title for itself, with

Orchid the second), and certainly the book that put the company on the small press comics map and established elements that would in many ways define the publisher over the next several years, was the anthology

Orchid. Featuring Victorian horror stories adapted by artists such as

Gabrielle Bell,

David Lasky and

Kevin Huizenga,

Orchid debuted at the Small Press Expo in 2002.

Although he's unclear about the exact provenance of the book in terms of Sparkplug's initial output, co-editor Ben Catmull described to

CR the origins of the book as a publishing project. "A couple of years before

Orchid, Dylan and I had contributed to an anthology called

Toxic Paradise. It was published by Slave Labor and edited by Landry Walker and Eric Jones. The theme was zombies. That gave Dylan the idea to edit his own horror-themed anthology. His initial idea was to have H.P. Lovecraft as the theme. For some reason he invited me to be the co-editor. I didn't know what that entailed. I just knew that I liked the idea of working with Dylan.

"I forget why but he changed his mind and wanted the theme to be adaptations of authentic Victorian horror stories. In theory this sounded like a great idea to me. But in reality I had never read any old Victorian horror stories. So I wasted most of the time frantically reading through lots of short stories trying to find just the right one. By the time I found one that excited me I realized that it would have been too massive to finish on time. So I fell back onto adapting something almost embarrassingly short.

"I think among the other contributors, Gabrielle Bell was the only one that I had suggested and the rest were invited by Dylan. Since Dylan and I lived really far apart I didn't really know how to stay involved with the production and distribution of the book. I ended up having so little to do with the making of

Orchid that it was out of Dylan's generosity that I was still credited as co-editor."

The resulting book was a consistently high-quality, well-written, engagingly drawn and strikingly well-conceived work featuring cartoonists that clearly deserved -- if not demanded -- a wider audience. It remains one of the strongest collective artistic statements made by the rising post-alternative generation of cartoonists that emerged of the late '90s/early '00s. The book continues to be sold in the Sparkplug Comic Books

shop, and is as compelling a work now as it was at the time of its initial publication.

Over the next several years, Sparkplug Comic Books published anthologies, solo comics, collections of previous work and stand-alone book volumes. Williams was specifically devoted to the pamphlet comic book, long the most accessible of the standard comic publishing formats, at a time during which most publishers scrambled towards the more beneficial math provided by the graphic novel/trade paperback model. Although Williams himself would likely shy away from any discussion of publishing highlights having passion and enthusiasm for all of his projects, among the best-received works Sparkplug released to the world were John Hankiewicz's

Asthma, Chris Cilla's

The Heavy Hand, Chris Wright's

Inkweed, David King's

Lemon Styles, Jason Shiga's

Bookhunter, Trevor Alixopulos'

The Hot Breath Of War and Rina Ayuyang's

Whirlwind Wonderland (with Tugboat Press). Sparkplug also published two of the best alternative comics series of the last decade: Jeff Levine's

Watching Days Become Years (page shown) and Elijah Brubaker's

Reich. It is difficult to imagine the majority of Sparkplug's projects finding initial homes elsewhere, or the larger world of comics over the last decade-plus without them. Over 50 creators and nearly a dozen anthology titles were affiliated with Sparkplug in either a publishing or distributing capacity by the time of Williams' passing.

Williams also became widely known in comics circles for eschewing sales avenues he found ethically unappealing or somehow not in line with Sparkplug's aims and goals. He shunned Amazon.com when similar publishers embraced the on-line bookselling giant. When dominant hobby shop distributor

Diamond tightened its sales requirements and this caused them to take an outright pass on Hellen Jo's spectacular and critically lauded

Jin And Jam #1, Williams withdrew his work from the Diamond sales gauntlet. He focused on putting work into comics stores through alternative routes such as direct sales and moving copies via the independent sales agent

Tony Shenton. Williams was an effective hand-seller of comics who displayed at any number of conventions, and was the most active alternative comics publisher and distributor in terms of routinely attending the 'zine culture's various public shows. He became an organizer with the

Portland Zine Symposium, and cited such shows generally as a key to reaching his comics' natural audience. The Sparkplug Comic Books web site, which facilitated direct sales of a different sort, has long been both inviting and easy to use.

In February 2009, Williams opened the DVD and bookstore

Bad Apple in Portland with Tim Goodyear, a project the pair had dreamed up in the previous year. Williams

told interviewer MK Reed in 2010, "We were both sort of feeling like we had some understanding of comics and wanted to do something we were both totally no good at. We're going to be continuing all kinds of stuff like that throughout our lives, it would seem. Both of us love movies and books and art, and we wanted a way to involve ourselves in the larger community of Portland." The store also provided Williams with a workspace through which he could pursue his Sparkplug-related activities.

Although his choices gave Williams the reputation of someone working counter to certain comics' business interests, his friend, the cartoonist and fellow distributor

Jason T. Miles of Profanity Hill emphasized to

CR that Williams' positions were not about a rejection of any arts or business culture but an embrace of self. "Dylan loved and devoured all forms of culture, both mainstream and obscure. Dylan ceaselessly sought and struggled to find a way for himself and others to proudly and fearlessly be themselves...

be yourself, even if that means you aren't going to appeal to 'mainstream taste' or 'alternative taste.' We're barely alive and its stunning to recognize how easy it is to succumb to shallow trends, whether aesthetically or commercially, all in the service to abate the fearful desire of wanting to be loved and accepted. Dylan bravely inverted this well-worn ego tread and helped many, many people to find and express themselves through art. He had such a gift for recognizing what made a person special."

During Sparkplug's fifth anniversary year in 2007, Williams rewrote

the page on his company's web site discussing the house's conception and general aims:

"Sparkplug Comic Books is a small publisher. The intent is to stay small, as small as I can keep it. I like the idea of getting little seen work to a wider audience. I've moved on from simply that. Also, it seems a little bit presumptuous and self-aggrandizing.

"Most of the work Sparkplug and I've published over the past 5 years has been put to print because I liked it, more than any other reason. So, I can't really claim to be publishing people whose work hasn't been seen by a wider audience. Ultimately it comes down to me liking the work.

"In looking back, the choice of work seems to have been based on the writing, first and foremost. Emphasizing the 'book' in comic book. And yet there have been visually based works as well. My chief requirement being that the work I've published made me think and challenged me as a reader, requiring an investment of time and thought."

In that same statement, Williams cited bringing on other books and minis from self-publishers that he admired as the biggest change in Sparkplug's first half-decade, and wrote that distributing comics he admired was nearly as much fun as publishing them.

Sometimes lost in the achievements that fell to Sparkplug was Williams' own cartooning work. His best-known comics were those found in the series

Reporter, although Williams created a number of considerable shorter works as well. Cartoonist, publisher and critic Austin English was a fan. "Dylan's cartooning is just as beautiful as his publishing, but perhaps less obviously pleasing -- Dylan might have liked that about it, the not-easy nature of it," English told

CR. Dylan is someone who loved Alex Toth but also loved 'vaguenesss' in storytelling. It's something Dylan talked about a lot -- how he appreciated 'unclear' art. And so you have a lot of Dylan in his cartooning: that obvious love for

Noel Sickles' cartooning coupled with perhaps the opposite of Sickles. I think one of the nicest things to be said about Dylan recently was that he would discuss '

Steve Ditko and

Fiona Logusch comics in the same breath.' His cartooning does this, too."

Sparkplug Comic Books became a consistent presence at the

Small Press Expo's Ignatz Awards over the last 11 years, pulling in 19 nominations and a win in 2003 for Jason Shiga's

Fleep in the "Outstanding Story" category. The number of honors won by artists with whom Sparkplug had some relationship, particularly early on in their careers, has and will continue to be felt outside of those with the official imprimatur. Regarding this year's "Outstanding Graphic Novel" winner

Gaylord Phoenix, its publishers Barry Matthews and Leon Avelino

posted on their Secret Acres blog on September 16, "Long before we came along, Dylan was buying up [cartoonist] Edie [Fake]'s extra

Gaylord minis and distributing them, and trading comics with him. He was offering any kind of support he could, because that's what Dylan did for cartoonists."

Williams had the attention and admiration of his peers. "Dylan was a super-interesting publisher,"

Fantagraphics Associate Publisher

Eric Reynolds told

CR. "Not just what he published, but how he published. Jason Miles and I have talked for years about this, about what a pure example Sparkplug has set for all of us publishing alternative comics. I think more than any other his contemporaries, from bigger companies like us and

D&Q to smaller ones like

PictureBox or

Buenaventura, Dylan really just published what he liked, for the sake of it, with virtually no concern for his own bottom line. If he had faith in the work, that was enough. That can be true for any of us, from book to book, but I don't think anyone was quite as consistent about it as Dylan. Look at his quiet devotion to the comics format -- the pamphlet format -- in the face of all logic. I doubt anyone in comics had better and more honest intentions as a publisher than Dylan."

Reynolds cited Williams' commitment to his artists as a key factor in his company's success. "His weaknesses somehow became his strengths, his integrity trumped his ambition and Sparkplug was the better for it. I know, for example, that Dylan loved established cartoonists like

Jaime Hernandez or

Dan Clowes. But I don't think he had any ambition to publish artists like that. They already had an audience; he would rather help someone like Austin English or

Chris Cilla find theirs. That's really something."

Working for an older, more established company and putting many of the same cartoonists into traditional bookstores via individual books and anthologies like

MOME, Reynolds respected the way that Williams sold Sparkplug's work through as many different channels as possible. "Dylan created a better grassroots network for finding homes for these books than just about anyone," Reynolds said. "I suspect he sold a smaller percentage of books in the usual marketplace -- comic shops and general bookstores -- than just about any publisher out there aside from maybe a company like Archie. I'm not even sure how he did it. It was clearly a byproduct of coming from punk and 'zine culture. None of which is to say he didn't want to make money. I think he very much wanted Sparkplug to pay for itself so he could simply continue to do what he loved doing, and I know he worked really hard at it. But I think he was happy being on the fringes, championing work that no one else would."

"More than anything, I admire how many cartoonists he encouraged and nurtured. He really befriended his artists; I sense he really cared about them as much as their work. I can't think of a guy off the top of my head who gave more of himself to comics and cartoonists. I loved Austin English's anecdote about Dylan telling him that 'selling comics was god's work.' I'm sure he said it with tongue-in-cheek, but on the other hand, he had clearly found his own higher calling."

English cited Williams as an inspiration for his own company. "Me starting

Domino Books is 100% a result of knowing Dylan," English told

CR. He described the generous nature with which Williams received news of efforts some people might have seen as competitive interests, and noted that Williams paid close attention to cartoonists he thought he could bring a wider audience "Dylan believed in encouraging people and he often resisted publishing people who he thought 'would get attention anyway.' That's to say, there were cartoonists he loved that were actively looking for a publisher that he avoided working with because he felt they would find support anyway. There were potentially popular books that he loved artistically that he could have published that he backed away from because he was sure those artists would find other helping hands. He published work that he felt needed to be published by him and supported that work relentlessly."

"Dylan's support of my work changed my life and I'm not alone -- it wasn't merely someone printing your work -- there was a huge amount of faith and belief that Dylan instilled in you and Dylan believed that was an important thing to do. If you believed in someone, you better let them know," English added. "If you worked with Dylan, you were a partner and he believed in the ebst aspects of you. At times that belief was hard to live up to and I think you often let Dylan down. But more often then not, you rose to the occasion."

David King described to

CR the experience of being published by Williams. "I've never dealt with any other publishers but I get the impression that unless he has some clout an artist can't just do whatever he wants if he's working with one of the bigger outfits." He described Williams an an editor with a light touch, someone with an eye on making the published work as close to that conceived by the artist. "My experience with Dylan on the three books I've done with him is that the whole project should end up exactly how I envisioned it and I never got pushed around editorially by him. I'm pretty sure he handled people differently, though, by being more involved or less involved in putting together books depending on the artist. He was a production junkie and we always talked a lot about the paper and InDesign or what-have-you. He did all the printing locally and always called me up from the print shop on the day the book was being printed and reassured me that everything was going to look OK."

"I think he was annoyed that I kept sending him oddball square books and he'd give me the business about it once in a while, but he was committed to doing right by the people he worked with and making good comic books," King wrote to

CR. "He never asked me to change anything. He always seemed genuinely excited and interested in the stuff I'd send him and checked in every now and then to see if had a new book in the works, probably his way of gently telling me to get busy when he knew I wasn't doing anything. We joked that

Lemon Styles might put Sparkplug out of business because it's overpriced and too big, but he did it anyway, which was pretty nice of him."

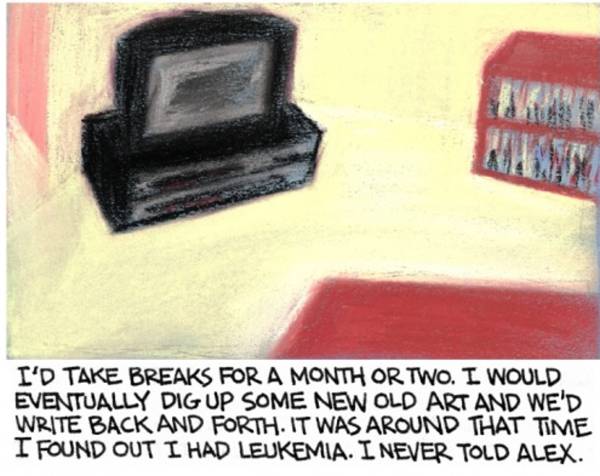

In "

Alex Toth," a short comic done for English published in 2009's

Windy Corner Magazine #2, Williams mentions a diagnosis of leukemia and discussing with the comics art great their mutual health problems. This is as public a confession that exists that Williams suffered from cancer starting with that leukemia, a series of diagnoses and setbacks that would eventually take his life. Williams fought the disease in its various permutations privately -- most had no idea he was ever sick, while others could never quite figure out exactly when and to what extent -- and with considerable dignity and tenacity.

"His initial diagnosis with cancer made him very aware of time," Landry Walker told

CR. "He hated to waste it. He was always very concerned with personal control, and despised the idea of any substance -- such as sugar or caffeine or alcohol -- controlling him. He was already a vegetarian when I met him, and had quit smoking cigarettes earlier as well. I watched him swear off caffeine, which was weird because he was obsessed with his morning coffee for years. But it was about health and control for him, and that was something that carried through to his handling of art and business." In

a short essay at

The Comics Journal,

Trevor Alixopulos described a changed man. "He had a touch that some people have when they've been breathed on by something large and final. He was a little less carefree, but had a depth of compassion that was all the more poignant because you could tell it was something that he wrestled into being, and continued to wrestle with."

Williams returned to the hospital in the summer of 2011 facing renewed complications from cancer. He revealed some of the basics of his situation on a Facebook post or two, and was immediately surrounded by a swarm of concern from friends and professional colleagues. On August 23, Williams

gave the nod to critic Robert Clough that he would be amenable to receiving support through the purchase of books from Sparkplug. This led to an extended effort by many on-line sources and comics community advocates asking friends of the company and comics consumers generally to consider buying works from the publisher. For many it brought into focus the wealth of Sparkplug's publishing catalog. Williams' friend Jason Leivian of

Floating World organized

a two-day sale at his Portland store, during which they raised money equivalent to two full New Comics Day's worth of sales for Williams. Leivian also organized

a books-and-art auction that drew support ranging from

Iron Man writer

Matt Fraction to cartoonist/printmaker

Jordan Crane.

Williams was apparently in relatively good health and seemed to many on the road to recovery when the Small Press Expo began the weekend of September 10. Friends

Tom Neely and

JT Dockery were manning the Sparkplug Comic Books table in Williams' place, in part in order to raise additional monies for the publisher. Word of Williams' passing hit the show in the second half of the Expo's first day, recasting the event, attended as always by a significant number of Williams' friends, fans and affiliated cartoonists, in a melancholic light. Most of the week of September 11 in the small press and independent comics communities was given over

to on-line tributes to the publisher and cartoonist, many extolling his considerate nature, intellectual curiosity and virtues as a friend.

Landry Walker related the following story to

CR. "When I was 20 years old I jumped on a stone wall out by the ocean and almost fell. Dylan grabbed me by the back of my jacket and saved me from what would have been a very bad fall. He wasn't the kind of guy who would even accept thanks for something like that. He seemed both embarrassed and respectfully amused by gratitude. I don't think he usually felt it was necessary. All he expected from people was to be listened to and treated with respect. You gave him that you had his absolute dedication."

Dylan Williams was laid to rest on Thursday, September 15, in Portland's Riverview Cemetery, attended to and remembered with abiding fondness by the community of people in which he was a valued, trusted member. Williams is survived by his wife, a father, a mother, and hundreds of cartoonists for whom he'll long remain a guiding light and beloved figure.

*****

My deepest thanks to Williams' friends and peers for taking time to answer questions during a very difficult week. Any correction as to factual information in the above would be greatly appreciated and more material may be added as new information on Williams' life comes to light.

*****

*****

*****