January 5, 2010

CR Holiday Interview #15—Jog On Death Note

CR Holiday Interview #15—Jog On Death Note

Joe McCulloch, better known as

Jog, is a one-person argument for the value of writing about comics on-line. His body of critical work that isn't ink on paper is, I think, better than anyone else's out there by a significant amount. He continues to find new ways to engage comics and I admire him for that. Jog was the first person I asked to be involved with this series, and he just as quickly responded with an offer to talk about

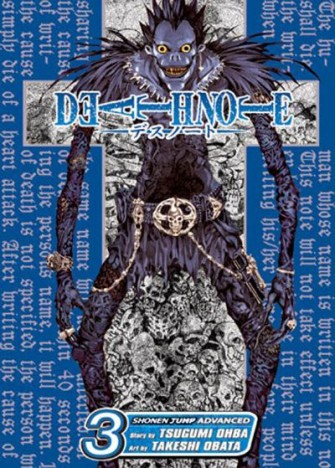

Death Note, by

Tsugumi Ohba and

Takeshi Obata. I was thrilled, and immediately curious. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: Jog, according to the time stamps on the e-mails it took you about 11 seconds to suggest Death Note

as an emblematic work of the decade. I know this is going to keep me from about five questions of my own generation, at least on the initial burst, but can you describe in broad terms why Death Note

so quickly sprung to mind?

JOG: Well, I was gonna do

the Punisher at first, but then I decided to keep the season classy by going with a teenager that discovers a

Shinigami death spirit's notebook with the power to kill anyone whose name is written in it and thereafter decides to crush human society into a malleable shape with an iron fist of justice -- much to the amusement of the aforementioned Shinigami -- thus kicking off a 2000+ page game of wits with a trio of eccentric boy detectives and a big, sexy supporting cast, probably sexier than that of the Punisher. A whole bunch of people die and we applaud, but maybe we feel bad, too!

But to get a little broader, when I think of comics this decade, I think of rapid expansion and fragmentation. Like, I don't know about you, but when I go back and look to the turn of the last decade, the millennial conversation, which I wasn't following comics to have experienced first-hand although I've tried to go back and study it, I get the feeling that people were hoping for a more unified comics in the future, as in a

Direct Market-dominant culture where maybe pamphlet-type comic books weren't necessarily the dominant format and the internet played more of a role and certainly where superhero comics weren't quite still so dominant, but fundamentally a similar place pushed a bit closer to where the mainstream of entertainment culture happened to be. From there came the search for the real/new mainstream of comics.

That didn't quite happen. What did was that webcomics inevitably expanded in one direction -- tied pretty strongly to gaming culture in its most lucrative, influential examples -- while bookstores opened up not so much as an adjunct to the options allowed English-dominant North American cartoonists but as an alternative distribution venue, geared in large part now toward a Young Adult-ish audience interested primarily in manga, although obviously it's not just teenagers reading the stuff. And there's a decent amount of literary-minded comics prone to attracting coverage from adult venues for prose literature coverage in there too, along with a bunch of superhero collections and bookshelf-aimed projects as well, but manga or manga-ish projects wound up becoming the dominant, public face of "bookstore comics," establishing essentially an alternate world of popular comics, as opposed to a popular world for alternative comics, if you get my drift.

Now, manga has a lot of blatant differentiating characteristics, particularly given that the bookstore boom was accompanied by the genius marketing scheme of not flipping the artwork to go left-to-right and then calling it "authentic," but even among as vaporous and form-defined a thing as webcomics you've probably noticed a certain lack of rhetoric spillover from dedicated webcomics readers to, say, superhero comics readers, or even avowedly comics-omnivorous outlets that mostly actually talk about print comics. In the same way, as a glance at the recent Top 10 of the Year or Decade lists will reveal, Western comics-focused or even miscellaneous geek or nerd culture-type forums tend to ignore manga, sometimes specifically begging off the topic for lack of expertise -- and it's a big area, no doubt.

The thing I'm getting at is, "comics" has gotten a lot bigger over the last decade, but it got big in a way that further exploded the notion of what "comics" were in North America, as per the subcultures devoted to comics reading. In fact, manga seems to be the new, popular place for casual comics consumption too, the supermarket checkout rack stocked with

Archie digests -- still here, motherfuckers -- mirrored funhouse-style as kids sitting around the shelves at

Borders where they don't tell you this ain't a goddamned library, and yeah some stuff gets bought.

And hey, now that

Archie is getting hitched to Veronica and Betty, and

Moose I think, like

Riverdale's now a polyamorous love dream city-state -- it's doing okay in comic book stores! Like, Diamond Top 100, 25,000+ copies okay! There should be a

Blackest Night tie-in where the Green Lanterns get married to other color lanterns to make a really pretty color, although I guess they're doing that with

Guy Gardner? I hope he marries

Midge next. But what I'm getting at is that the spillover between reading groups is limited, or it sure seems so based on our always-limited grasp of sales numbers, anecdotes - I'm very much aware that folks prone to writing about comics or running comics-friendly websites tend to be devoted to their favorite kinds of comics, so maybe a bit less prone to going on about a really wide swathe of the form. They stick to specialties, and in 2009 I think we're at the point where what's dominant in comics is well and truly tied to various workable -- if not lucrative -- distribution formats, so specialization doesn't denote an interest in niche-of-the-niche comics.

So, to answer your question, which I think was about

Dennis Eichhorn, but I'm just gonna answer the question in my head right now:

Death Note was the last comic I encountered that for a few bright, blazing moments seemed to bring all the tribes together. This is a personal thing, based on observation, but I think I observe a lot, and I damn well remember just about everyone nodding in

Death Note's direction, from the lowliest junior high

Narutard to dedicated art comics scribblers to random LiveJournal personages to gentlemen prone to detailing the meta-fictional aspects of

Infinite Crisis. I'm not saying everyone read all 12 books and the Official Guide, but an extremely broad selection of broken bigger comics read some of it, and even that, today, is amazing. To me, that makes it the emblematic mainstream comic of the decade.

SPURGEON: I agree with you that Death Note

kind of crossed all of comics' inner borders for a time there. Do you think there's a notion that a popular series like this one also gets some power, some of its appeal, out of not quite breaking wide? Does that allow for easier ownership of something, that it's apparently not for everyone? Even within manga, is there anything equivalent to liking this book or set of books over that book or set of books as a personal signifier?

JOG: Hmm... well,

Death Note didn't break quite as wide as something like

Dragon Ball did; it broke wide in comics, not necessarily in the wider U.S. culture, as perfect an original cable series the comic would make. Yeah, I think maybe some fans feel a bit more attached to it because not everyone knows -- I mean, lots of comics folks know about it, so you can converse and argue, but it isn't so spread out to defeat the precious nature of it.

My impression within manga is that

Death Note admirers tend to like how dark and cruel it is in addition to the funny parts, the suspense mechanisms; the gloss of moral complexity (ex: "Is Light justified in his mission?!?!") is appealing, though I personally don't think it's very substantive. Still, it gives it a leg up on other manga in its class --

Viz had it under their Shonen Jump Advanced label, which works for me.

With manga, fan "ownership" goes different ways, though, sometimes going beyond the text or referring to the basic communicative aspects of the text itself. There's a big aspect of authenticity zeal to some hardcore fans --

Shaenon Garrity made a reference on TCJ.com the other day to flamewars erupting over Viz's decision to translate Light's name as "Light" when some fan translators had it down as "Raito" because there's no 'L' sound in Japanese -- although a character named L is okay, since it's an in-story Roman letter -- which gives you an idea of how these things sometimes go.

And then there's "character" fans, which is how a finished series like

Death Note can survive -- frankly, the fact that not all of the story's plot maneuvers work for every reader encourages fans to ignore the stuff they don't like and imagine their own adventures for their favorite characters. Not that any of that stuff is unique to manga, but

Death Note got the effect off the ground very fast, with dead-basic but appealing characters to obsess over and a big toolkit of ideas (some of them pretty lightly used in the series proper) to fool around with.

Popular manga tends to be very adept at encouraging this kind of fandom quickly out of the gate, where appreciation of the work doesn't necessarily relate to what the work actually says, or how it functions in a literary sense; put simply, they're big stories, but then they stop. Then everyone becomes a little like superhero writers or legacy artists on a newspaper strip, only without much pay or anything, not too big an audience, but shit -- how big an audience does comics get? This is the makeup of

Comiket in Japan, unoffocial spin-off stuff like that, lots of fucking,

fan service -- original comics are famously harder to sell. You're better off making a porno computer game. Would you like to hear my pitch, Tom? It's about comics critics!

SPURGEON: I'll pass. [laughs] Now, I take it when you call it a finished series that Death Note

is done?

JOG: You are right. The main

Death Note series was serialized from 2004 to 2006 in Japan, with a somewhat different pilot episode in 2003 and a jokey "sequel" episode in 2008, so it's purely of this decade. The 12 Viz collections were released between 2005 and 2007, so it came out in English extremely quickly, if not quite as quickly as it did in, like, Taiwan. I think around the time Viz's English editions were just getting started the series was banned in several Chinese cities, having drifted in via piracy and Chinese-language imports. It appears to have been successful almost wherever it goes;

Anime News Network tells me it just wrapped its Polish translation, with the Hungarian edition about halfway through. I mean, this is the kind of comic where you've gotta be careful to specify English-dominant North America when you're talking, because it's also been released in Mexico.

For what it's worth, it's also one of the few U.S. releases of its age where I still routinely see full runs stocked in bookstores, just loose copies, not the box set -- 'cause there's a box set, too. Granted, for as popular a work as it was in Japan, selling tens of millions of comics and spawning a 37-episode television anime adaptation, two anime television specials, three live-action movies, two prose books, video games, etc., the creators pulled the plug fairly early. The writer, Tsugumi Ohba, notes that the series ends on Chapter 108, to symbolize the 108 Earthly desires in Buddhism.

SPURGEON: A lot of criticism on manga is done when series are in progress and I wondered if being able to look at the complete work here has an effect on how you're able to grapple with it as a reader and as a critic?

JOG: Oh sure. I mean, I initially read

Death Note while Viz was still releasing it, because I'd heard a lot about it, and at that time it was still an ongoing series in Japan. It's funny, because there's different tiers of popular manga readers, so that while casual readers or good consumer readers are dutifully following the official English releases you've got a different bunch of folks following scans of the Japanese releases, sometimes right off the pages of the serializing anthologies, with English text Photoshopped in by Japanese-equipped readers. That meant that you'd be following the series, and if you'd look around online you'd get people going "Aaah, they fuck it all up when L dies in vol. 7," or griping about how they hate the ending and stuff.

So, despite being a bit like reading this week's

Marvel comics while consulting the webcam bug you've planted on

Matt Fraction at a contemporaneous story retreat, it wasn't that different from reading any serialized comic as it happened and later going back and looking it over as a whole.

I'm glad you brought this up, because I think the initial wide appeal of

Death Note -- among sects of comics readers, not society at large, let's make no mistake, even though a couple high schools got mad over kids making their own kill notebooks, and, y'know, there's not too many things I take for granted in this world, but if schools are banning your comic you're probably on the right track as far as I'm concerned -- came from the process of reading it as a serial, even if it's a serial that's actually batches of serialized chapters collected into a dozen books. That's still a serial.

Death Note

Death Note, you see, is a plot machine. If, as the old saying goes, manga is different from Western pop comics in that it's more about going somewhere than getting there,

Death Note splits the difference by making virtually every chapter a small destination. It's a suspense comic that's just diabolically focused on plot points, dozens and dozens of them, everything swirling around Light the ambitious kid's efforts to evade capture while killing the shit out of criminals so as to reform the world, initially powered by new "rules" regarding how to use the deadly notebook, every one of them providing fresh fodder for cat 'n mouse contortions, but later just sprawling all of this accumulated background over expanded scenarios. What if Light loses his memory for a while? What if other Shinigami show up with extra Death Notes? What if we fucking kill the series' most popular character right here and replace him with two characters representing (a) emotion and (b) full

Vulcan? Oooh, how do we get out of this, dear readers??

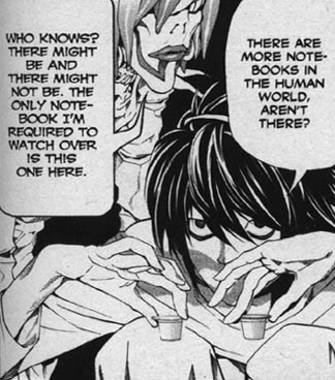

In this way, the suspense becomes almost as much about wondering how the plot isn't going to collapse into a heap than which of the characters are going to survive. And to be frank, the characters in

Death Note exist pretty much to drive the plot anyway; they're really catchy character types, and the artist, Takeshi Obata, does a decent job of giving them striking looks, but they never, ever, ever develop at all, in any but the most superficial ways! When someone enters the

Death Note stage, you can bank on them playing out that role, as you know it right there, for the whole series, which effectively short circuits your typical boys' manga focus on the development of a large cast of characters in a loose -- if ideally propulsive -- story.

Death Note is anti-decompression; it's dense, dialogue-heavy and all but soaked in ideas, all of which feed the roaring engine of who-knows-what-now, does-he-know-that-I-know-that-he-knows, et al. At risk of dealing in stereotypes, this plot point mania is fairly Western in style compared to your

Naruto or your

One Piece.

Even among series today, the closest artist I can think of working in this vein is

Naoki Urasawa of

Monster,

20th Century Boys and

Pluto, although he's a writer/artist that weaves a lot more in the way of theme and color and complexity into his stories, despite their being longform suspense pieces. He's been picking up some of readers outside the "expected" manga readership --

Pluto is really the key here, as it's almost eerily similar in basic outlook to Marvel's early

Ultimate superhero books in redoing a classic action fantasy character (

Astro Boy) in a modern, nominally sophisticated setting. I actually wonder how well he does with that typical manga reader, since he's writing for an older audience, and his sedate, not-so-"manga" looking art is more common to

seinen manga of that type; most of the visual tropes that maybe freak people out in manga are really heavy in

shonen (boy) and

shojo (girl) comics.

And do not forget:

Death Note, as much as this can boggle the mind, is a kids comic. Not a little kids comic, like in

CoroCoro or something, but it's shonen manga, it ran in

Shonen Jump. Ostensibly it's aimed at 12-year old boys, which brings to my mind

Grant Morrison's old line that

New X-Men was aimed at intelligent 12-year-olds, even though I'm sure he fucking well knew the real audience is 20, 30 and up. This isn't unique to American superhero comics.

Take the term "boy." That denotes both age and gender. There's a good quote from Obata in the

Death Note official guide,

How To Read -- this is where I'm getting all my

Death Note factoids, by the way -- where he attributes the series' wide appeal to the fact that it didn't seem like a typical

Shonen Jump manga, "although it actually was, really." But what

Death Note really does with

shonen manga is that it takes the classical

shonen elements, defined by

Jason Thompson as friendship, perseverance and victory, and subverts and mocks them with this story of your typical dedicated manga boy hero who perseveres in not getting locked up for all the criminals he's killed with the Magic Item he's come into, and strives with clenched fists to reform the world under his moral authority. To be the best, like it's a sports manga!

All his friends he just uses; it's all fake and shit, because everyone's using each other, especially in the bit where L, the favorite detective kid, calls him his first friend. L doesn't give a shit! He's out to beat Light, to win the game of

Death Note -- the chase after the value of victory destroys friendship, and turns struggle into amoral destruction. Nobody fucking "wins" in

Death Note, by the way -- the detectives go in neat alphabetical order: L, M(ello) and N(ear), and Near's the one that defeats Light, who dies, and then the world just goes back to how it was before, and I for one was left with no doubt that Near would just eventually be killed by someone else anyway, not that he seems to care; it's telling that he's the least human-like of the eccentric boys.

It's

shonen, but it's like old, angry

gekiga: it has an old soul, that of adult manga aimed at kicking the snot out of Japanese optimism, correcting society. When you back away from

Death Note, the fun of serialization, when you look at it as a whole, it's an awful thing. It's sheer nihilism. As a whole, it's all about how stupid, useless people are pushed around by powerful boys and men with the balls to command the brainless sheep of society, even though their efforts are inevitably immoral and any attempt at substantive change is doomed to failure. There is no God, there is no life after death, we all just trudge through the slime of corruption and literally the best we can hope for is to curtail the worst abuses so as to maintain the crummy status quo. Fuck you, and good night.

It's not necessarily there to make you sad, more to urge you to live life and give it your all because that's all you can ever do -- a man without hope is a man without fear, as Jesus said. And there's a place for that! Ohba has said that part of the reason

Death Note was pitched to a

shonen magazine was because they're be less focus on theme, more on action -- as a result, intentional or not, it's like a perfect, horrible machine of scattershot acid commentary, delivered like thrilling entertainment! For a while, anyway; part of

Death Note's monomaniacal focus on plotting is that once the plot gets shitty for readers, they jump off. It's somewhat hard to find many

Death Note fans that actually liked the whole series.

Which naturally leads to the boy-as-gender part of the equation. Death Note may be nominally aimed at males, but it's part of something some American readers have dubbed "

neo shonen" -- comics for boys that take great pains to attract girls, often through attractive male character designs and appealing relationships, maybe with the added zing of

yaoi appeal, though not generally actual homosexuality. If I was gonna be a huge boy about it, I'd say that

Death Note has a lot of ugly sentiments toward women in it, based on the fact that virtually every female character in the series is either a helpful idiot, blithely exploited or quickly killed.

That's not giving the series' female fans -- and there's plenty of them -- enough credit. Part of the fun of

Death Note, and I haven't talked nearly enough about fun here, is how the characters are all so wicked, yet latched onto this steaming plot engine and all sorts of novel bang-pow concept twists. I was rooting for L to, say, crack down on freedom of the press or subject Light to tortuous interrogation (often above the futile objections of some silly, minor moral voice, swiftly brushed aside) to see if he'd "win" the series. I think for women and girls the fact that all these handsome, get-things-done guys use all these mostly awful women is a similar part of the enjoyment, although certainly all women aren't the same!

Ha, this is a good topic, because you're right now you're probably going "infant Christ in the cradle, Jog, do you even

like Death Note?!" And the answer is: sorta! What I'm getting at is --

Death Note was a weird, curious series for Japan, for its manga demographic, and what made it odd is probably what helped its popularity here, and it finished smashingly well there and here, at a time where here became increasingly affected by there. In this way, as a finished unit, it straddles the line of what's expected of manga both in the manga-fied U.S. and in Japan, while representing a possible, now even likely future. I can't think of another comic this decade with such unique qualities, and it's got a visceral, immediate appeal that, for however brief it lasts, can't be denied.

SPURGEON:

SPURGEON: Death Note

was originally "sold" to me by a Viz editor on the floor of Comic-Con not on the main, conceptual hook but on Takeshi Obata's involvement. Even today, he seems an odd choice to me, and I don't know if there's a story there or not. Anyway, can you talk specifically a bit about his work as a designer and artist on the series, whatever your feelings are about his contribution?

JOG: Well that makes sense, because they had to sell the comic somehow when it was really fresh and unknown. When you see how odd it is,

Death Note is really kind of a risk despite its huge popularity in Japan; there's always a chance the aspects of it I'm deeming "Western" won't actually appeal to North American English readers at all. So I presume they looked for some tie-in, something familiar. Back in the '90s you'd always want to latch on to an anime tie-in when releasing manga, despite the fact that the manga would almost always have reached a bigger audience than anime adaptations in Japan. This tail-wagging-the-dog effect led to some odd stuff, like Viz putting out some old

Galaxy Express 999 movies and relatedly releasing a bunch of

Leiji Matsumoto manga that remains the most of the guy's work ever seen in English on this continent.

Even today, manga remains somewhat closely tied to the wider anime culture in English-dominant North America, which isn't to say that anime is a thriving business -- it's pretty much in the shitter at this point -- but that pirated and

fansubbed and out-of-context anime on the Internet is so common that it's an engine.

Death Note's anime didn't start up until 2006, so that wouldn't work -- I presume Viz went for Obata-as-sales-point since

Hikaru no Go, one of his prior projects as artist, had already been out in English for a couple years.

All this anime talk is funny, since I see Obata as exemplary in the youth manga effort to adapt a very slick, stylized-realism "anime" approach to manga -- glossy character designs that look like they stepped off of model sheets planted into detailed settings like old-timey cells on buffed backgrounds. It's a very lush approach, with fewer speed lines or iconographic details that'd denote the doodling of capricious pictures; I find it very chilly myself, machine-like and still, in the way that a lot of television anime these days doesn't even move very much.

But, y'know, that approach is fitting as a system of delivery for chit-chat and plot information. The writer Ohba is supposedly an artist, too; he scripted

Death Note via dialogued thumbnails, which I think is how

Mike Mignola does some of his

Hellboy-related comics, keeping a grip on the base look, the storytelling. Calling Obata a "designer" is maybe most accurate, given that he also works pretty heavily with studio assistants -- those 2000+ pages didn't get seralized over two years two-handed! -- and he is a damn appealing character draftsman, and adept at shadowy mood or the occasional good facial expression, and I wonder if looking like anime but not necessarily so much "manga" helped bridge the gap of appeal between the manga audience and other comics readers.

SPURGEON: You mentioned earlier about the various spin-offs and presentations in other media, and how they were releatively restrained. Still, I think of Death Note as this group of material rather than a couple of films over here and a manga series over there, and I'm not sure why that is. Is it wrong to suggest that the manga has a closer than usual relationship to the other forms in which

SPURGEON: You mentioned earlier about the various spin-offs and presentations in other media, and how they were releatively restrained. Still, I think of Death Note as this group of material rather than a couple of films over here and a manga series over there, and I'm not sure why that is. Is it wrong to suggest that the manga has a closer than usual relationship to the other forms in which Death Note

works have appeared? How closely interrelated are they for fans, do you think? Did the films or any of the other material change the way you look at the manga at all? Does that happen to you generally?

JOG: I'll say again, it's a pretty short series as far as shonen megahits go, and it's complicated enough in terms of basic concept -- to say nothing of its focus on plotting, which naturally endears those specific plot points to readers, as opposed to the general idea of

Monkey D. Luffy and his seafaring world of rib-tickling hijinx -- that the various spin-offs tend to hew close to the original. Even the farther-off stuff like the L-focused material tend to be oddly similar; the

L: Change the World movie and the

Death Note Another Note: The Los Angeles BB Murder Cases prose novel have almost exactly the same basic concept -- L vs. another eccentric kid from eccentric detective breeding ground Wammy's House that's gone bad, although they both take it in different and twisty directions.

The thing is, the

Death Note manga is such a unique thing as a whole, this anti-theme

shonen semi-parody that gains in bleak, awful impact from its dutiful, probably kinda thoughtless accumulation of plot baggage, the semi-faithful stuff is especially responsive to small changes.

Part of this is the issue of fandom:

Death Note is over. Done. Yet the fans keep it going -- more and more of them seem to be female, which maybe justifies the decision to appeal not just to guys, and perhaps plays into a certain stereotype of girl fans as especially glommy with their favorites -- which is fine for sparking interest in remakes and new properties. I'm convinced the sheer flatness and lack of development of the series' characters helps it in this way -- it's easier to hook onto really catchy "types" and read your own nuance into them than deal with preexisting complexity. Really,

Death Note almost seemed to cry for a fandom, and it got it -- in a world of closed-period stories like manga offers, this isn't a bad model for creators looking for nice money from finished work.

But fandom creates its own baggage. The first two

Death Note movies were a two-part adaptation of the "main" work, which actually only covers the bits with L and then skips to the very end -- as you've definitely figured out by now, L is the really popular character. Plus, L beats Light in the movie, and dies a peaceful, heroic death.

For me, this actually causes kind of a huge problem, introducing heroism into

Death Note! Because L is an awful mother fucker. He tortures, he suppresses freedoms, he clearly doesn't give two shits about anything in comparison to the thrill of figuring out a good puzzle -- and, you know, in the comic he dies like a dog, like Light eventually dies like a dog, and Near survives but he'll probably die like a dog eventually -- the 2008 manga postscript actually deals with another guy finding a

Death Note and just getting destroyed in one episode, mind you, but that's more a joke about how hard it is to repeat a big success; I think the story was released in anticipation of Ohba's & Obata's current series,

Bakuman, which is about high schoolers that want to be manga artists.

Getting back on topic though,

Death Note the manga has that cruel elegance to it, in that everyone is doomed, and that temporary success may be the realm of the immoral, but it's all hubris in the end. Yet popular L gets his day to win in

Death Note the movie, and suddenly -- he's a beloved character, so he's the hero. All the awful shit -- faithfully reproduced from the source material! -- is A-OK. It's necessary to stop the real evil! That's fucking repulsive!! It's way worse than the manga! But that's what happens when you put popular character A (er, L) in a seemingly stronger place. I don't know if the filmmakers were mindful of L's fandom or anything, but it still says something.

Then you get the L movie, which seems hellbent on undoing the mess of the proper

Death Note movies, which gets me thinking the implications didn't go unnoticed (ooh, maybe that's my hubris!) -- like, it's a pretty campy, light adventure L goes on to solve one last case after beating Light but before dying, and he spends the whole movie learning the value of life and repudiating his old ends-justify-the-means attitude, and all the death scenes are pretty disquietingly oozy and overlong, as if mocking the quick, pretty deaths of kids' comic

Death Note -- it makes me feel like I'm in the story, Tom. Did the director know that the other director knew that Tsugumi Ohba knows that... that...

SPURGEON: Why didn't we have a major

SPURGEON: Why didn't we have a major Death Note

-related controversy in some school somewhere? For that matter, why haven't we had a big manga-related controversy of any kind? I guess there was a Dragon Ball

thing with the wee-wees somewhere I can't even remember now, but I thought at one point that we were going to either have 50 of those or the one we'd have would be super-dire seeming.

JOG: I have no idea. Man, I remember the time a bunch of old copies of

Urotsukidoji somehow slithered out of the CPM archives and showed up at Borders -- some of 'em weren't even shrink wrapped! The secret ingredient is: it looked old, so none of the kids probably even opened it. Burden of pop, Tom.

Anyway, with

Death Note, it's good to remember that there's a lot of dying, but it's all very clean. Most of it's quick heart attacks -- that's the default mode of notebook killing -- and any of the nastier, specific deaths you can write in are depicted with restraint, especially considering the likes of

Fist of the North Star of

shonen series' past. I don't think it'd necessarily fly by the Comics Code Authority in 1957, but it is mostly a violent series about wishing people were dead really really really hard, which tends to go on in high school anyway, so finding a few kids scribbling "Bobby Pinkerton -- hit by his dumb fukking car" isn't going to cause too much of an uproar. The basic deadly item that kills via your desires concept isn't new, or new to manga -- there's a similar idea in

Hideshi Hino's Panorama of Hell, and that wasn't even the first time he used it.

But yeah, I guess I'm a little puzzled at how some of the precocious girls jonesing for

yaoi haven't caused an uproar, given the general outlook of society in re: non-male and/or non-hetero sexuality. If I had to lay money down, I'd say that most parents don't particularly understand these wacky backwards books to start with, and they maybe don't have much of a concept of cartoony-looking comics having a lot of squicky content. Thanks, Dr. Wertham!

SPURGEON: How much is the worldview put forward in

SPURGEON: How much is the worldview put forward in Death Note

a serious, considered one and how much of it is undercutting that which gets asserted in other manga? Or is that just a pathetically false dichotomy? How do readers engage with the series on that level, do you think?

JOG: I don't think a lot of readers engage on that level at all, because they're not supposed to. [Spurgeon laughs] That's why it's a

shonen manga, because there's less burden of questioning on it -- I think only lit majors, sociologists and huge nerds like me think of it that way, but that stuff is an element of it. If you read interviews with Ohba, he tends to be very evasive about deeper meanings in

Death Note, like: "We never put much thought into it. We just wanted it to be entertaining." That's from

How To Read.

It mirrors some sentiments you get from pro

mangaka, like when

Kiyohiko Azuma won the a Japan Media Arts Festival prize for Yotsuba&! in 2006 and he emphasized in his interview that he doesn't consider his work "art," and that he doesn't even want to be an artist, he wants to be an artisan. And I suspect this is an odd and maybe troubling thing to hear in the comics scene around here, where we like to imagine sometimes that everyone is struggling to do traditionally deeper things, "elevating" genre pieces, while manga has the benefit of actually having been a mass medium, steadily for decades now, with economic structures in place to support craftsmen and a wide variety of works coming out, and I expect that's fostered less anxiety over literary fiber in individual works -- in some cases, entertainment craftsmanship is essentially the goal. Well-done plot points could be their own reward, even in the abstract.

You see? I think we're nearing the reluctance right up proper critics have in dealing with manga, popular manga. Relaxed. I can sense

Gary Groth writing my name in his

Death Note right now; that's why I use a nickname. You think Gary has Shinigami eyes?

But anyway, here were are in the 21st century, the end of the first decade of that, and it's clear by now that we all can process works apart from authorial intent, so

Death Note is what

Death Note is. I'd say a good half to three-quarters is probably a product of its plot mechanisms clanking around to eliminate obstacles, keeping readers on their toes, which on the level of truly devious plot craft perhaps encourages the overall tone of the work. It may not be timed to the last word -- like, I'm not even convinced its response to shonen tropes was meant to be more than a hooky means of getting the series picked up a huge, big money magazine -- but it's a serious result nonetheless.

SPURGEON: It's weird, I'm usually a themes and moments guy, and I'm usually focused on the original works, but I think my lingering memory of this series is going to be watching one of the live action films and being struck by how awesome the design was for Ryuk.

SPURGEON: It's weird, I'm usually a themes and moments guy, and I'm usually focused on the original works, but I think my lingering memory of this series is going to be watching one of the live action films and being struck by how awesome the design was for Ryuk.

JOG: Hell yeah, Obata knows his design. And it's especially important that Ryuk look cool because --

Well, think about it. What does Ryuk, the main Shinigami even do in the story? He provides a helpful way to break up the monotony of talking heads, yes - when in doubt, cut to Ryuk. But he just hangs around. Observes. He started the story, dropping off the Death Note, and he ends it, writing in Light's name. Sometimes he participates in the action, but only to facilitate his own delight at what's happening.

The characters in

Death Note are flat. Types, like I've said. So specific-yet-vaguely-defined it's hard to even locate a reader identification figure, and they're mostly monsters anyway.

Except Ryuk, a literal monster. A death spirit. He's the reader identification figure, because he floats above everything, unconcerned. The official guide calls him lazy, but he's really just relaxed, like reading a comic on the train. It all means nothing to him -- these people are like fictions he can watch smash into one another, just like we're watching the Death Note passion play of silly fucking futility, of dumb fucking society going nowhere in high style, "reality" made sick for thrills, just like Ryuk did. A whole bunch of people die and we applaud, and maybe we don't feel so bad at all. We've got our own Shinigami death realm to sit in, boring before distraction.

That's entertainment, Tom. Happy holidays.

*****

*

Death Note (Box Set), Tsugumi Ohba and Takeshi Obata, Viz, Twelve Volumes Of Manga Plus How To Read, 142152581X, October 2008, $99.99.

*****

This year's CR Holiday Interview Series features some of the best writers about comics talking about emblematic -- by which we mean favorite, representative or just plain great -- books from the ten-year period 2000-2009. The writer provides a short list of books, comics or series they believe qualify; I pick one from their list that sounds interesting to me and we talk about it. It's been a long, rough and fascinating decade. Our hope is that this series will entertain from interview to interview but also remind all of us what a remarkable time it has been and continues to be for comics as an art form. We wish you the happiest of holidays no matter how you worship or choose not to. Thank you so much for reading

The Comics Reporter.

*

CR Holiday Interview One: Sean T. Collins On Blankets

*

CR Holiday Interview Two: Frank Santoro On Multiforce

*

CR Holiday Interview Three: Bart Beaty On Persepolis

*

CR Holiday Interview Four: Kristy Valenti On So Many Splendid Sundays

*

CR Holiday Interview Five: Shaenon Garrity On Achewood

*

CR Holiday Interview Six: Christopher Allen On Powers

*

CR Holiday Interview Seven: David P. Welsh On MW

*

CR Holiday Interview Eight: Robert Clough On ACME Novelty Library #19

*

CR Holiday Interview Nine: Jeet Heer On Louis Riel

*

CR Holiday Interview Ten: Chris Mautner On The Scott Pilgrim Series

*

CR Holiday Interview Eleven: Tim Hodler On In The Shadow Of No Towers

*

CR Holiday Interview Twelve: Noah Berlatsky On The Elephant And Piggie Series

*

CR Holiday Interview Thirteen: Tucker Stone On Ganges

*

CR Holiday Interview Fourteen: Douglas Wolk On The Invincible Iron Man: World's Most Wanted

*****

*****

*****

posted 2:00 am PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives