January 2, 2010

CR Holiday Interview #12—Noah Berlatsky On The Elephant And Piggie Series

CR Holiday Interview #12—Noah Berlatsky On The Elephant And Piggie Series

Noah Berlatsky

Noah Berlatsky is the prolific critic behind the team blog

Hooded Utilitarian, which was folded into the

TCJ.com family in early December. One of his choices was

the Elephant and Piggie series, from the illustrator and occasional cartoonist

Mo Willems. The re-emergence of comics for a wide variety of children is definitely one of the major comics publishing trends this decade, both from comics publishers and from traditional ones, and the Elephant and Piggie books are not just reminiscent of comics but straight up examples of the form. I'll let Mr. Berlatsky explain the rest. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: Give me the basics on this one, Noah. I know Elephant and Piggie

is a series, and I think it may be aimed at the kids in the first half of elementary school. How many books are there -- what's the scope of our discussion here?

NOAH BERLATSKY: Willems' books are actually generally aimed younger than elementary school; my son loved them from when he was three, probably, and still enjoys them at six, though they may be getting just a little young for him. The Elephant and Piggie series has multiplied fast; Willem started writing them in 2007, and as of now

trusty wikipedia lists ten, with another (

I Am Going!) scheduled for early 2010. I think we've read them all and own almost all... at least in theory. Finding things on our children's bookshelf is, alas, often a dicey proposition.

SPURGEON: I know Mo Willems as a cartoonist more by his travelogue in pictures You Can Never Find A Rickshaw When It Monsoons, and am only aware of the success of his career in kids' books, not so much what that work is like. How did you discover this specific work? Are you a fan of Willems?

SPURGEON: I know Mo Willems as a cartoonist more by his travelogue in pictures You Can Never Find A Rickshaw When It Monsoons, and am only aware of the success of his career in kids' books, not so much what that work is like. How did you discover this specific work? Are you a fan of Willems?

BERLATSKY: That's funny; while I have vague name recognition on his travelogue, I've never seen it or even read very much about it.

I found Willems because I'm a dad, so we're often in the children's book section. I don't remember anyone recommending these even; I think we just picked one up at the bookstore and loved it.

Since then we've found a number of his other books and series, and, yeah, they're all pretty great. His pigeon series ("

Don't Let the Pigeon Drive the Bus!") is maybe as good as Elephant and Piggie. The

Knuffle Bunny series is extremely cute as well. He's got a couple of others that I don't like quite as much --

Naked Mole Rat Gets Dressed has one of those "everyone be yourself!" morals that I kind of never need to read in a children's book again. But generally, yeah, he does great work.

SPURGEON: What made you think of this work specifically in the context of comics? Is the work like a pair samples I've seen on-line in traditional comics form? How much work have you seen in children's books that's more or less is comics and how much is merely reminiscent of comics? What would you suggest if someone were interested in doing some exploration of those kinds of works?

SPURGEON: What made you think of this work specifically in the context of comics? Is the work like a pair samples I've seen on-line in traditional comics form? How much work have you seen in children's books that's more or less is comics and how much is merely reminiscent of comics? What would you suggest if someone were interested in doing some exploration of those kinds of works?

BERLATSKY: I don't think it's an issue of seeing it in the context of comics; Willems' work is comics. He uses cartoony simplified animal characters and makes extensive use of comic tropes like motion lines and speech bubbles. The narrative is entirely advanced through sequential action; the movement and words of the characters directly tell the story; it's absolutely not text with illustrations. Some of the chicken books even use panels. The only reason you wouldn't call it a comic is because it's not sold through the direct market, basically.

I think in terms of what's out there in children's books that I've seen, that are like comics, Willems is maybe out on one end of a continuum, but he's certainly not alone or unique. Children's books regularly make use of speech bubbles, for example, and many of them mix comics tropes with some text explanation in varying degrees.

Obviously there's

Maurice Sendak's

In The Night Kitchen, which is a

Winsor McCay tribute.

Mercer Mayer's

A Boy, A Dog, and A Frog is a wordless comic; many of his other classic books rely on images to move the story (as in a couple of spots in

There's A Nightmare In My Closet.)

Sandra Boynton uses speech bubbles liberally, and her books can often read as comics I think.

Satoshi Kitamura is a Japanese expatriate living in Britain who writes both manga and manga-influenced books; and plays very consciously with ways that comics can be children's books and vice versa.

Calef Brown's stuff looks a lot like

Fort Thunder... I think there are really lots of examples. It's true that a lot of it maybe wouldn't be called comics by

Scott McCloud, but I think in some ways that actually indicates it's healthier, more adventurous medium.

SPURGEON: Are you familiar at all with Toon Books? Those are comics outright, although one difference is that because Francoise Mouly wanted them to be of value to children in an educational sense you have some input as to the types of language that will work, the clarity of certain visual keys... where does that kind of comics effort fit into your fluid continuity between the two forms?

SPURGEON: Are you familiar at all with Toon Books? Those are comics outright, although one difference is that because Francoise Mouly wanted them to be of value to children in an educational sense you have some input as to the types of language that will work, the clarity of certain visual keys... where does that kind of comics effort fit into your fluid continuity between the two forms?

BERLATSKY: I haven't seen these, though I did see the Spiegelman/Mouly anthology

Little Lit which I thought was pretty dreadful overall. There are a number of great comics for kids, though.

Jill Thompson's

Magic Trixie is a favorite in our house.

Lewis Trondheim's

Li'l Santa books are great, too... and for that matter, my son really enjoyed having me read

Asterix to him. The

Marvel Adventures series vary widely in quality, but are overall pretty good... and the DC children's series

Tiny Titans is particularly good, making use of a more children's booky art style that also happens to be vastly superior to most of the art in mainstream titles.

I think more superhero comics aimed at kids and marketed as children's books seems like a no-brainer in a lot of ways. Marvel and DC have taken some steps in this direction... but really, the market there seems potentially much larger than the Direct Market, it seems to me.

SPURGEON: What do you think makes successful character designs for works like these? It struck me looking at a photo of the stuffed animals that Willems nailed something here, but when I look at the actual drawings I'm not sure I can qualify what exactly that it is. Why do these characters work, particularly for their intended audience?

BERLATSKY: I'm not sure I can really answer that exactly; four- to six-year-olds like lots of things for reasons I find more or less baffling (

Bakugan... I confess; I don't get it.) I can talk a little about why I myself find Willems work effective, though. He has a lovely line -- not sure what he's using exactly, but he gets a lot of texture, and the forms are simple but fluid. His facial expressions are wonderful too; he's got some great eyebrows and does wonderful things with mouths and eyes. It reminds me a little of

Kate Beaton, actually; just a real knack for expressing a lot with a few strokes.

SPURGEON: In your essay on the books, you suggest that they have a slapstick quality that strips don't have anymore. What exactly do you mean by slapstick quality? Can you pinpoint that? Because these don't seem exemplars of slapstick: they're not out of control or super-manic or close to violent. Is there something essential here that makes something slapstick in your eyes that doesn't have to be pushed to the nth degree?

SPURGEON: In your essay on the books, you suggest that they have a slapstick quality that strips don't have anymore. What exactly do you mean by slapstick quality? Can you pinpoint that? Because these don't seem exemplars of slapstick: they're not out of control or super-manic or close to violent. Is there something essential here that makes something slapstick in your eyes that doesn't have to be pushed to the nth degree?

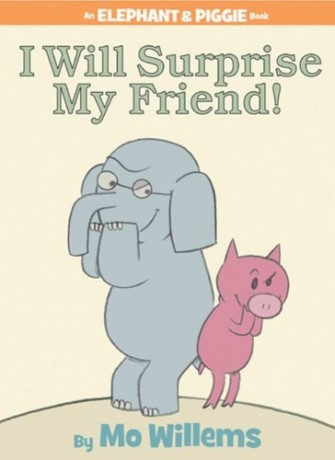

BERLATSKY: I guess what I was thinking of here is the way that the characters are so much in motion. They're always skipping and bounding, moving around the page in complicated patterns with dotted lines showing their paths. Even if they just stand there he's often got motion lines showing how and where there feet and heads and hands are twitching. You're right of course that they're very gentle books; nobody's getting crushed by rocks or even hit with pies. But there's an energy there that still says slapstick to me, even if it's just the moment in

I Will Surprise My Friend where they jump out from behind a rock and scare each other so badly that they leap in the air and shriek and fall over backwards.

You hardly see that kind of expressive, expansive physical humor in contemporary comic strips, it seems to me, because, among other reasons, there's just not room. Part of the effectiveness of Willems' humor and movement is that it occurs on a full page. Reduce it down to strip size and some of those motion lines would pretty much completely disappear.

I could be wrong here I suppose; I don't read a ton of strip comics these days -- I guess the one's I'm most familiar with are

Get Fuzzy and

Dilbert. And I actually think both those strips are funny -- though

Dilbert is remarkably ugly. But I certainly don't see much use of this kind of physical humor in either of them, nor in other strips I've occasionally glanced at. As another example, if

Chris Onstad was a third of the cartoonist Mo Willems is, I might actually find

Achewood tolerable.

SPURGEON: Why do you think strips don't have that manic quality anymore? Is it a cultural development, a formal restriction based on size, a self-consciousness about low-class roots?

BERLATSKY: Well, as I said, I think a lot of it is size for newsprint... though why it's the case for webcomics I really can't fathom. Though you know, if I have to pull something out of my posterior, it could be that webcomics aren't really for kids for the most part. I think a lot of the physical humor is something kids really enjoy especially. I think adults, on the other hand, can be satisfied by just having some punchline about the HR department even if the drawing looks like a kind of stale wad of gum that would probably sigh and fart and expire if you even suggested to it that it might put a motion line over near its left elbow there. And if you can be satisfied with that... well, good drawing is difficult and rare. Folks who can do that can probably make a living doing something more likely to be lucrative than webcomics.

Though, to be fair, Kate Beaton is a fine artist... though she doesn't really do the kind of slapticky action I'm talking about either. I don't know. The truth is, I don't know enough about webcomics to speculate about this very effectively.

But why let that stop me? You know, most monitors aren't necessarily going to allow for full page movement either the way the elephant and piggie books do. I think there's an argument to be made that physically and logistically, books just do this sort of thing better than computer screens, at least at the moment.

SPURGEON: How much about how the Piggie and Elephant books work has to do with its very basic but obviously effective coloring? Can comics learn anything from children's book illustration in terms of visual language?

BERLATSKY: I don't think the color work in Mo Willems is necessarily spectacular; he keeps things pretty simple, and it looks fine, but I don't know that I'd make huge claims for it beyond that. I think if you were going to learn something from Willems' color work, it might be "first do no harm." And, yeah, god knows that colorists on mainstream comics could stand to learn that lesson.

SPURGEON: What exactly were you suggesting in terms of a move on-line as a possibility we'll see more work of this type from comics-makers? It seems like you're talking about that cartoonists will be able to take more time to work on more material, but then you cite as a counter-example PvP, which is a daily strip.

SPURGEON: What exactly were you suggesting in terms of a move on-line as a possibility we'll see more work of this type from comics-makers? It seems like you're talking about that cartoonists will be able to take more time to work on more material, but then you cite as a counter-example PvP, which is a daily strip.

BERLATSKY: I was thinking of more time and more space. I probably didn't know anything about the mechanics or timing of

PVP when I said that except that I thought it was (and that it is) ugly. But... perhaps the demand for daily content on the web could explain part of why there hasn't been an impetus to try more formal experimentation, or at least variation.

SPURGEON: It seems like you're for a greater variety of ways of doing things generally, that you have an aversion to the kind of ossification that come with hard categories and boundaries. Is that a fair assessment? It seems like the decade has been really push and pull that way, with a lot of hybrids being published but also a stronger definitional sense of comics. Would comics in general be better off if folks embraced and paid attention to more forms of visual storytelling than the ones usually strictly defined as comics. Is that where comics is going?

BERLATSKY: I think it's a fair assessment more or less, at least in regard to comics. I don't think it's a particularly controversial stance to say that American comics with the direct market has gotten itself in a rut in terms of both genre and marketing that it would do well to try to get out of. Some of the alternative models -- like manga -- I quite like; others, like the more literary memoirs following in the wake of

Maus, I'm not such a fan of; still others, like webcomics, I'm largely ignorant of. But, yeah, aesthetically and market-share wise, I think comics can only be aided by trying to reclaim some of the limbs that have been lopped off over the years. And I think children's books could certainly be an important part of that.

*****

*

Watch Me Throw the Ball!, Mo Willems, Hyperion, picture book, 64 pages, 1423113489, March 2009, $8.99

*

My Friend is Sad, Mo Willems, Hyperion, picture book, 64 pages, 1423102975, April 2007, $8.99

*

Today I Will Fly, Mo Willems, Hyperion, picture book, 64 pages, 1423102959, April 2007, $8.99

*

I Am Invited to a Party!, Mo Willems, Hyperion, picture book, 64 pages, 1423106873, September 2007, $8.99

*

There Is a Bird on Your Head!, Mo Willems, Hyperion, picture book, 64 pages, 1423106865, September 2007, $8.99

*

I Love My New Toy!, Mo Willems, Hyperion, picture book, 64 pages, 1423109619, June 2008, $8.99

*

I Will Surprise My Friend!, Mo Willems, Hyperion, picture book, 64 pages, 1423109627, June 2008, $8.99

*

Are You Ready to Play Outside?, Mo Willems, Hyperion, picture book, 64 pages, 1423113470, October 2008, $8.99

*

Elephants Cannot Dance, Mo Willems, Hyperion, picture book, 64 pages, 1423114108, June 2009, $8.99

*

Pigs Make Me Sneeze!, Mo Willems, Hyperion, picture book, 64 pages, 1423114116, October 2009, $8.99

*****

This year's CR Holiday Interview Series features some of the best writers about comics talking about emblematic -- by which we mean favorite, representative or just plain great -- books from the ten-year period 2000-2009. The writer provides a short list of books, comics or series they believe qualify; I pick one from their list that sounds interesting to me and we talk about it. It's been a long, rough and fascinating decade. Our hope is that this series will entertain from interview to interview but also remind all of us what a remarkable time it has been and continues to be for comics as an art form. We wish you the happiest of holidays no matter how you worship or choose not to. Thank you so much for reading

The Comics Reporter.

*

CR Holiday Interview One: Sean T. Collins On Blankets

*

CR Holiday Interview Two: Frank Santoro On Multiforce

*

CR Holiday Interview Three: Bart Beaty On Persepolis

*

CR Holiday Interview Four: Kristy Valenti On So Many Splendid Sundays

*

CR Holiday Interview Five: Shaenon Garrity On Achewood

*

CR Holiday Interview Six: Christopher Allen On Powers

*

CR Holiday Interview Seven: David P. Welsh On MW

*

CR Holiday Interview Eight: Robert Clough On ACME Novelty Library #19

*

CR Holiday Interview Nine: Jeet Heer On Louis Riel

*

CR Holiday Interview Ten: Chris Mautner On The Scott Pilgrim Series

*

CR Holiday Interview Eleven: Tim Hodler On In The Shadow Of No Towers

*****

*****

*****

posted 2:00 am PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives