December 19, 2011

CR Holiday Interview #1—Art Spiegelman

CR Holiday Interview #1—Art Spiegelman

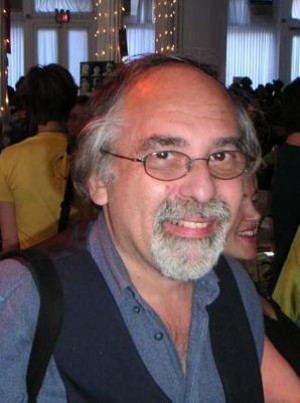

Art Spiegelman

Art Spiegelman is

an award-winning cartoonist, a celebrated

writer about comics, a crucial figure in comics history that straddles

two generations of comics-makers, one of the

most important editors in the medium's history and

the current Grand Prix winner going into next month's Angouleme Festival. December 2011 finds Spiegelman on the very tail end of his press work supporting the release of

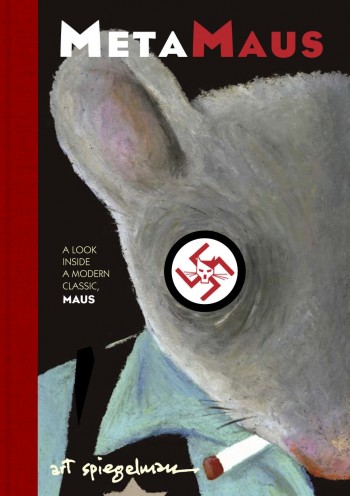

MetaMaus, a well-received exploration of his groundbreaking graphic novel success

Maus on the occasion of its migration to book form a quarter-century ago. Spiegelman is also gearing up for the exhibits and press demands of the massive French-language comics festival. I am extremely grateful he made the time for this interview, and I always enjoy talking to him. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: Can I ask you about France right off the bat? You've had a crazy last month, I know, being over there and putting the finishing touches on some of the exhibits and participating in their publicity cycle.

ART SPIEGELMAN: Sure. Actually, it's more like it's been a crazy year-plus. The last couple of weeks were especially nuts. You can ask me about either.

SPURGEON: I was wondering about the direct build-up to the Festival. You're the Grand Prix winner, which puts you square in everyone's sights as the Festival gets closer. How has that experience been in terms of all the attention, and how are your preparations going for your contribution to the show?

SPIEGELMAN: I'm finally beginning to see light at the end of what seemed like an endless tunnel on that stuff. Actually, when I was first invited in, I was trying to figure out how to get out of it without creating an interational freedom-fries like incident. [Spurgeon laughs]. Because it's very nice to be made the maharaja of comics or something. Either too soon or too late, you know? It should have happened either 15-20 years ago or maybe 15-20 years from now where they could wheel me in on a respirator. But right now it wasn't good timing.

The way it was presented to me was, "Call this number in France at 10:30 in the morning to say thank you to

Frédéric Mitterand, the minister of culture, when he names you the president" -- whatever it was, the grand prize winner, the grand marshal -- "of the next Festival as he announces it to a tent full of a thousand people." So it was sort of like a

fait accompli. It wasn't like I was being asked would I consider it. So I had to call up, and all I could really do as a kind of caveat -- because I was flattered, of course, but I also am aware that various other presidents I've met as friends fall into a black hole once they've been given this honor. In France, if you live in France, it makes a lot of sense that you do it. From far away, I'm not so sure. So my response, short of one of those kind of jingoistic "You crazy, cheese-eating surrender monkeys, go peddle your pornography elsewhere" or something, I had no clue as to how to wriggle out of what I knew was going to loom as a big deal. So I just promised to try and do as good a job as the last American president,

Robert Crumb.

SPURGEON: [laughs] As I recall, Crumb didn't show up much at all.

SPIEGELMAN: He was considered kind of a disaster. [laughter] They vowed never to give it to an American or maybe even a foreigner ever again. I was annoyed they had broken their promise.

Crumb was friends with Jean-Pierre Mercier, who worked in Angouleme and was able to put together a great retrospective show of his work. I was there that year. I haven't been there that often, but I was there that year. I hung out with Crumb in the tent that functions as a green room for the major celebrities where no press can get in and so on. And he just never went out. They'd come by with dispatches saying, "Would you go on

Arte-TV for an interview? Can

Le Monde talk to you?" The answer was always, "Nah." [Spurgeon laughs] That lasted for one afternoon where people he knew were hanging out with him back there. The next day I think he sort of said, "Screw this," and went off record hunting in old flea markets in that region of France. And that was the end of it, except I think he made a brief appearance at the judging. I wasn't there for that, so I don't remember for sure, but somebody said he did. The rest of it...? He had to make a poster, and his poster was considered so lurid that the metros and buses wouldn't put it up [Spurgeon laughs] and they had to come up with a last-minute other poster. So I figured that was a low-enough bar, to try and match that.

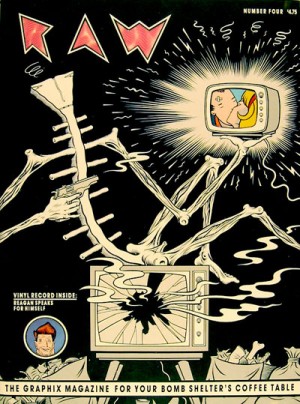

SPURGEON: I worked with you years ago on a couple of issues of The Comics Journal, where we ran a long interview you did with Gary Groth. I remember how specific you were about certain artists, how strong and idiosyncratic your curatorial sense was. Now, am I to understand you're putting together a retrospective of RAW for the festival?

SPURGEON: I worked with you years ago on a couple of issues of The Comics Journal, where we ran a long interview you did with Gary Groth. I remember how specific you were about certain artists, how strong and idiosyncratic your curatorial sense was. Now, am I to understand you're putting together a retrospective of RAW for the festival?

SPIEGELMAN: Well, there's different things, different aspects to this. Bit by bit, my obsessive-compulsive controlling self got involved. So that instead of just going, "They do what they want, I do what I want" from the get-go, they were trying to make it easier on me and I made it harder on myself to do this somewhat well. Although there are certain areas where it's just not reasonable for me to get involved. I'm just not there.

My involvement had to start with this retrospective show of my work. That was one of the main obligations. That was the first thing I said "no" to, as soon as I had a private conversation with somebody. That created a problem off the bat. I just can't spend whatever it would have been, four months, going through all of my old art, to fill a large exhibition space. So I suggested they blow up some cartoon work I've done and put it up. But they then came back with one of those offers one can't refuse. So I was then dragged into that show. The offer one couldn't refuse was to have the show then travel to

the Pompidou Centre.

SPURGEON: Nice.

SPIEGELMAN: First time for any contempo comics artist, I think. Although as I found out, it's in a venue that's unorthodox. It's in a bathroom on the way to the

Matisse show. [Spurgeon laughs] But nevertheless, there's a show, rather large, 400 square meters is now what it looks like it will be. I don't even know what it is in feet [approximately 4300], but it's large. So it can contain it. That made it all something I had to consider and deal with even though the main theme of my life is that I've just been hijacked. The cartoonist Art Spiegelman has died. I've been reincarnated as the executor of his estate. And now I hope someday to die and be reincarnated as an underground cartoonist. But I can't quite get there yet. So that show will now happen. And I was able to work with

Rina Zavagli,

Lorenzo Mattotti's wife Rina, who has a fantastic gallery in Paris. She was game to take this on. That made it possible for me to do the show. I trust her with my life, let alone my work. She had a very attractively arranged show of my work in her then brand-new gallery a year or two back.

So that was in place. So I was doing that. Then I made my life more complicated by saying yes to something that has its real complications. There's two museums in Angouleme. There's the festival's building, which I think used to be the old regions museum, I think it's called the Castro building. That has my retrospective. I haven't been back in Angouleme to see it, it's only about two or three years old, but now

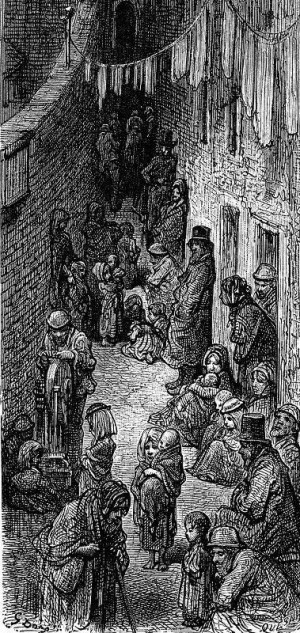

there's another museum. The Angouleme museum that's connected to the school that's there all year round. It's not administered the same way. I was interested in that museum and going there as soon as I got to Angouleme, because it's the museum of the French patrimony of comics. So that has really obscure -- for us certainly -- comics by

Gustave Doré and other 19th century proto-comics that are very interesting to me.

So there was an overture. They needed to get a photo of me because I was president and they needed it for

the CBIDI museum, and then I said, "It'd be easier for me to come out and visit," and eventually what it led to was [sighs] the second museum exhibit in Angouleme, which is basically, it's being called "Art Spiegelman's Private Museum" -- "musée privé" or something. I get to hijack their museum and put up an American patrimony. That will include the

RAW artists. It starts with the 19th Century material I'm interested in, because I wanted to see it. Then it moves primarily toward the American comic strips, comic book, underground comix.

It allowed for several things that I really wanted to have happen. One was to pay tribute to

Bill Blackbeard, who died last year, because without him there's not much of an American patrimony. That will be part of the early Sunday pages. The museum has some, I have some, and I was able to kind of arrange for other material that's going there as well.

Jenny Robb of the Ohio State University collection was willing to help this thing happen. That meant access to Blackbeard's actual pages that are in

the Billy Ireland collection, which is an airplane hangar sized collection. Also,

Glenn Bray was indispensable. He has an airplane hangar-sized collection of original comics art, mostly in the alt- and underground comix category as well as

EC Comics. So a bunch of things are being borrowed from him. I'm working with

Thierry Groensteen as my lynchpin in France. And being helped by

Bill Kartalopoulos. But in record time and with a lot of friction in some ways, because the two organizations aren't smoothly turning gears. The second show will allow for the

RAW work to be shown and the early comics work to be shown, all of which I consider as something that should have been part of my retrospective. But just to keep it more focused, there's one that's the retrospective and one that's the "roots and peers" show.

I think I answered a question in there somewhere, I'm not sure. [laughter]

That show will have for instance

Binky Brown's original art, all of it, from Glenn's collection, in a separate little room at

CIBDI. And my work in my retrospective, I think there's something from when I'm 12 years old. It's a scary retrospective. Certainly from the age of 17 to now there's a lot of work, most of which hasn't been seen in Europe or here.

SPURGEON: Let me ask you this now instead of later. You referred to yourself as an underground cartoonist. I think of you that way. You're one of the younger underground cartoonists, but...

SPURGEON: Let me ask you this now instead of later. You referred to yourself as an underground cartoonist. I think of you that way. You're one of the younger underground cartoonists, but...

SPIEGELMAN: You've put me in among these old geezers. [laughs]

SPURGEON: Well, that group of cartoonists is

aging. And some have passed away now. Do you think we have a proper grasp on the artistic legacy of the undergrounds? Do you think there's still work to be done there?

SPIEGELMAN: If this kind of museological patrimony of American comics style book keeps coming out, eventually we'll finally get that part as well. In this corner of publishing, there are the most astounding books of old comic strips, like -- the most impressive one, but there's so many, is probably

the Forgotten Fantasy book from Sunday Press, which made feel like I'd died, or was in a dream I wasn't waking up from, and saw this book that can't possibly exist. But then also the complete runs of everything from

Peanuts to

Dick Tracy to

Little Orphan Annie and now coming up

Barnaby and so on is an amazing zeitgeist shift. There is a history. That's happening for comic books as well, whether it be

Mort Meskin or

Alex Toth or the EC stuff or

Little Lulu, the comic book thing is coming together. Oddly enough, there's no real equivalent for underground comix.

Back in the day, there was this movie called

2001 and humanity passes through a monolith and changes and evolves? Basically, underground comix was the monolith for comics.

SPURGEON: Is it that we don't have a grasp on how much things have changed, or we've just kind of forgotten?

SPIEGELMAN: Boy, is that for sure! I feel so far outside the loop at this point, you know [laughs], even though it's a loop I guess I helped make. Yes, at the moment. things feel so comfortable. Even if there's not a lot of money associated with being an alternative cartoonist, you can go into any club or bar in the world, hold your head up high and say, "I draw comics." And that wasn't the case. It was better to say you were a plumber.

SPURGEON: [laughs] I guess that kind of leads to

SPURGEON: [laughs] I guess that kind of leads to MetaMaus

, in a way, in that the new book serves as reminder how far ahead of its time Maus

was and how much the context of how we look at it has changed in the years since. I know you've talked about a little bit, but one of the remarkable things about the appearance and success of Maus

was that it jump-started a publishing interest in comics that the material wasn't there to cover.

SPIEGELMAN: I think the phrase I was using when that was part of my sound byte repertoire was "Comics have to achieve to critical mass," meaning there have to be enough comics for critics to actually care about. So the first attempt at making a graphic novel section really got filled with Dungeons and Dragons books quick. After enough time passed people were able to make enough books that were clearly substantial:

Chris Ware and

Charles Burns and beyond and around, that the section started to stick. Now it's beginning to get Dungeons and Dragons books back in it, but they're much better produced.

SPURGEON: What I thought was interesting is that that you've also talked about the toll this had on you as an artist, trying to put this together out in the wilderness without a guide map.

SPIEGELMAN: I like that moment. Because of a question I've been asked a couple of times -- I'm just an interview victim these days [Spurgeon laughs] -- is "What would you do if you were starting to make comics now" or some variant of that question. And I wonder if I would at all. Because part of the lure for me was traveling through

terra icognita that most people didn't know about or care about. There was no cultural demerit given for not knowing who

George Herriman was, for example, back in the day. So part of it was the struggle of seeing what could be made in a medium that had no pejorative in my mind as a medium. But that wasn't the norm. The shift is so radical is that it's really hard for 20- or 25-year-old cartoonists to know what the frontier days were like. It had its advantages. There wasn't a hovering critical presence. It allowed for comics to retain a certain kind of vitality that arguably could be said to under threat in the environment we're in right now.

SPURGEON: Do you wonder about the limiting effects that Maus

might have had simply in terms of being first out of the gate? In that beating a path for people through the wilderness you're denying them the possibilities of having worked these things out on their own?

SPIEGELMAN: Of course. I mean, certainly

Maus was gestated in and continued with

RAW Magazine, which was an attempt to make it as clear as possible that there are many paths to making comics that aren't mired in commercial consideration. So that was a given from the get-go. On the other hand, one of the things that happened with

Maus -- just to address the first part of your question, the context was so different.

MetaMaus does go into that. The Holocaust wasn't a subject matter, a trope, a genre as it was just described in the

Times for a movie by

Agnieszka Holland -- the Holocaust

genre -- and that wasn't the case when

Maus was being made.

It was good subject for a story for me not because I wanted to make the world a better place by indicating that one must never do such things again, but because it was a story worth telling for me. It was a story that wasn't that known. I was interested in making a story, and I draw slowly and with some difficulty, and that was the right thing to do to fulfill the vision of "a long comic book that needs a bookmark and has to be re-read." That was the phrase I used before the punchier "graphic novel" took hold as a phrase. So in that context, the subject matter, without much context even in prose books until about the time I was in earnest making pages for

Maus. The late '70s. At that point, there was a zeitgeist shift. And the for comics, there wasn't much of a context, outside of maybe some things in underground comix when people discovered that work in

Arcade or whatever.

Within that zone it was very, very different than what it turned into. Even now I find that what happened was

Maus on the one hand opened a door, and [laughs] frog-marched into the culture on one side by

The Dark Knight and the other side

Watchmen, but it's the one that was sort of the odd man out in that group of three by not even having any basic connection to comic books as Americans knew them. So there was that.

Maus, on the other hand, created a situation for me and I think other comic artists that came in its wake, which is Holocaust trumps art every time as a subject. So I've gotten perceived as kind of "You're the guy that wrote the

Auschwitz For Beginners book." On the one hand, by people that have no interest in comics,

Maus was sort of a crossover hit with people that just don't read that kind of thing, thank you. On the other hand, it also created a situation for other comic artist as well as for me. The Holocaust is a hard act to follow. What do you do you to make something that people will tend to? And like we were just talking, it took a while for that kind of work to come to the foreground.

SPURGEON: Is there any element to

SPURGEON: Is there any element to MetaMaus

that's critical of subsequent works that have been created? A lot of folks' initial reaction has been to be staggered by the amount of material and amount of research and sketches you've included. That's not always the case with books that have followed. Is there anything about what you've presented that you wanted to put out there in terms of the seriousness and amount of work involved in your putting together that book?

SPIEGELMAN: No. One of the three questions that always was coming up was "Why did you do it in comics form?" To me, it was just built from the ground up, the answer is essential. It's not because there are mouse heads on these characters. That was something that's now made available, something that can be understood: that there's a comics grammar, a way pages are put together that's just basic to what I understand comics are.

I'm not saying that other artists have to do it my way, not by a long shot. All that I would say is that there is work that is thoroughly grounded in understanding the grammar that one works with. It's something I like in literature, too, when a writer can make a decent sentence, as opposed to another writer who I admire with all my heart,

Phil Dick, who couldn't get from subject to predicate [laughs] without a lot of side trips. I love what he does, but he's not a great writer. I think he reads better in French, probably. But he's a great philosopher.

Okay, end of parenthesis. There's not one way to make something important, except that it be urgent. I would say that's much more important than are you willing to read a library full of background material, or travel around the world to do the research for locales that are specific to specific projects.

SPURGEON: So do you see a lack of urgency from some of the work that's followed?

SPIEGELMAN: Yeah, some of it seems like knitting. But some of it seems amazing. I think we're living in a time where there's probably more great comics art coming out than at any time in my lifetime, certainly.

SPURGEON: I looked for a critical reappraisal of Maus

through the publication of this new work. There wasn't a lot of writing like that, but one idea struck me. Someone -- I think maybe David Ulin, although now I can't remember -- suggested that a central idea in Maus

is that an event like the Holocaust makes closure impossible.

SPIEGELMAN: I haven't seen the essay. This is about

Maus, not

MetaMaus?

SPURGEON: Yeah. And I think what hit me about the idea of the book engaging the inability to find closure is that it goes right to what a lot of the broader discussion of Maus

over the years has concerned itself with: your decision to include your story as an artist working with this Holocaust narrative and these relationships you had right next to the narrative itself.

SPIEGELMAN: That comes to the urgency part of this thing. I wasn't as aware of it consciously. I remember back to when I was in -- I'm not sure this made it into the final interview that ran in

MetaMaus -- at the time, all I knew was that thing about wanting to make a comic book that needed a bookmark and could be re-read. I had a few projects in mind, and one of them I left behind because

Maus seemed harder, and I wanted to take on something that would test my mettle. The other book was to be the life of a fictional cartoonist who lived from the beginning of comics to the then-present, when I was working. It was made up of artifacts of his work, and a history of comics sort of sewn into that. I think somebody must have done it by now [laughs] or variants of it, but at the time that was an alternative project I was considering. Part of the unconscious pull of taking on the thing that was hardest was to stare down the family legacy and the way it kind of distorted me and my relationship with my dysfunctional family, of course.

Closure, on the other hand, may only be possible in fiction and ten-cent therapy. It's not unique to the Holocaust, but the Holocaust is the example writ as large as it can be writ. But it's built into the actual structure of the

Maus book itself. It's sitting on this tombstone, and the past and present are kind of blurring. One ending that indicates a happily-ever-after kind of ending as delivered by my father, and then the compounded ending that lands on that tombstone. I think that's indicative of what closure is. Closure is probably just a tombstone.

SPURGEON: You mentioned early on in this conversation about wanting to get back to being a cartoonist, and it's something that's come up several times in your sound byte activities over the last several months. [laughter] You expressed that you hoped this book would have a positive effect on you as a cartoonist. Do you still think it will?

SPIEGELMAN: I sure hope so. I sure hope so. That was the bet I placed, I will say. The problem for me is that this has become... what I'm thinking of is that if I get to have another chapter in my life of one kind or another, I'd like to finish with this chapter, which is The Great Retrospection. It was a period where first I went and looked at

Breakdowns again. Oh, that's a book I can put out, my publisher is game to let me, I'll just do an introduction... two years later I deliver myself of a book, an introduction half as long as the book, and a postscript explaining the introduction. That was a two-book arrangement with Pantheon that also included

MetaMaus, which I think was supposed to come out with the 20th anniversary. And I put it off because it was harder.

Then just as I was sort of like finally getting to the end of what was a much more difficult project than I ever let myself know -- I now understand why I was putting it off -- "Okay,

MetaMaus. I'm seeing the light at the end of the tunnel." And then bam, this great art retrospective falls on my head. And that means looking back at any piece of art that I've made that wasn't a part of

Breakdowns [laughs] and

Maus as well as looking at it in a different context in terms of what could be part on a wall and make a good show. It's been very intense. And now until the other side of that show, which as I said is going to the Pompidou and as of last week has made my life even more complicated because now I have to do a catalog for that show before it opens at the Pompidou. So I don't quite know exactly when I get my life back, but I'm hoping when it does I'm kind of not going to expect myself to have to draw mice.

SPURGEON: Let me ask you one last thing. Looking at the book and hearing you talk about the retrospectives in France, it occurs to me how much collaboration you do. You listed that all-star team with whom you're doing these exhibits. That's very, very different from the perception of cartoonists as people locked away in their rooms, working alone. Has your collaboration been beneficial to your work as a cartoonist?

SPIEGELMAN: It's definitely been beneficial to the world of comics. I think. It's just how I understood the career option, to use a word I don't like: career. Because

Harvey Kurtzman was such an inspiration, I thought, "Oh, cartoonists are supposed to write, they're supposed to draw, and they're supposed to edit." It was just part of the job description. So early on that's how I entered into it. I became more interested in shaping books than making comics that didn't go anywhere. So that kind of collaboration, of being an editor -- although I find some times when there's an editor and I'm the cartoonist it makes my head explode [laughter] -- nevertheless, when it's done well, editing has a real function. So there was that kind of collaborating.

Here, on this particular book, on

MetaMaus more than any other book I've done, yes, it was built on an interview with

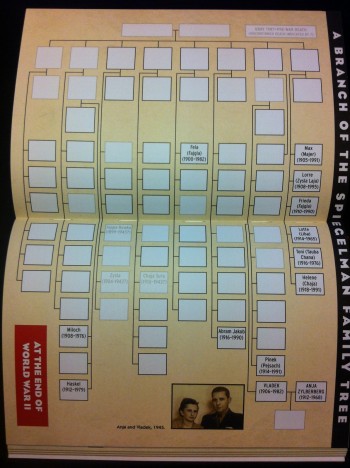

Hillary Chute. She was indispensable while working on it. To me the strongest two pages in the book are built on something my old cousin Sy Spiegelman made which was this geneology which included the pre-War and post-War genealogical tree. This amazing infographic, placing the people in

Maus in the context where they're a fractal of what happened. The corner of the family tree showing the children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren of a patriarch, and then after the war the very few names that are left and a lot of blank boxes, peole that died during the war years. That is a totally collaborative thing that is the essence of what this book offers in terms of answering why the Holocaust. So there's that kind of thing.

In the last few years, I've been more overtly collaborative. I don't like collaborating on my own comics. I don't want to write for somebody else to draw, because other people can't draw badly just the right way. [Spurgeon laughs] I certainly wouldn't want to draw for somebody else's writing. So that's out. On the other hand, it gets lonely here in the studio. When projects come up, I'm at least willing to entertain them on a certain level. Over a long period of time I was involved with something that never quite happened but someday still may, which is the

Drawn To Death: The Three-Panel Opera musical theater thing that made me realize how lucky I was to be trapped in a studio where you didn't have to interest bankers in every step of what's going on.

The past year or so I did a project that used some of the ideas from

Drawn to Death, working with a bunch of dancers who came over to the studio and invited me to collaborate on a dance. A medium that has no special interest for me, but I loved collaborating with them, making a comics dance piece with shadows and drawings interacting, drawings of dancers. The only drawing poster I've done in the last year outside of a poster for Angouleme was what will be an eight-foot-high by 50-foot-wide glass window for what had been my old school,

the School Of Industrial Art and the High School Of Art And Design. As they move into a new building, there will be this large kind of stained glass window that overlooks the cafeteria from above -- how do I describe it? -- it overlooks the cafeteria and upstairs there's a corridor where you can the image from behind. This thing that I've kind of built works with what you see from the front, what you see from behind, and what images are on this window, which in some ways is comics stuff. That involves working with master craftsmen in Germany; it's being fabricated as we speak. I'm going to see it right after Angouleme to approve what they're doing. That will be installed when the school opens next Fall. So that's also a kind of collaboration. I have to make something that I wasn't going to do hands on. I have no idea how to make a stained glass window as a craftsperson. But I made something that's now being translated. That's another kind of collaborative work, I guess. I need both.

Right now what I need is the non-collaborative work. I really need it badly. I hunger for it.

*****

*

MetaMaus, Art Spiegelman, hardcover, 9780375423949, October 2011, $35.

*

Festival International De La Bande Dessinée D'Angouleme

*****

* photo of Art Spiegelman from a MoCCA Festival from a few years back

* RAW will be a part of one of the exhibits with which Spiegelman is involved at this year's Angouleme Festival

* Gustave Doré

* underground-era work from Spiegelman

* the new book

* some of the sketchwork that went into

Maus

* that astonishing Sy Spiegelman infographic

* from the

MetaMaus introduction (below)

*****

*****

*****

posted 4:00 am PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives