January 13, 2015

CR Holiday Interview #4—Susan Kirtley

CR Holiday Interview #4—Susan Kirtley

Susan Kirtley

Susan Kirtley holds a masters and a PhD and is currently employed at Portland State University as an Assistant Professor. I met her at the academic conference held in conjunction with the opening of the

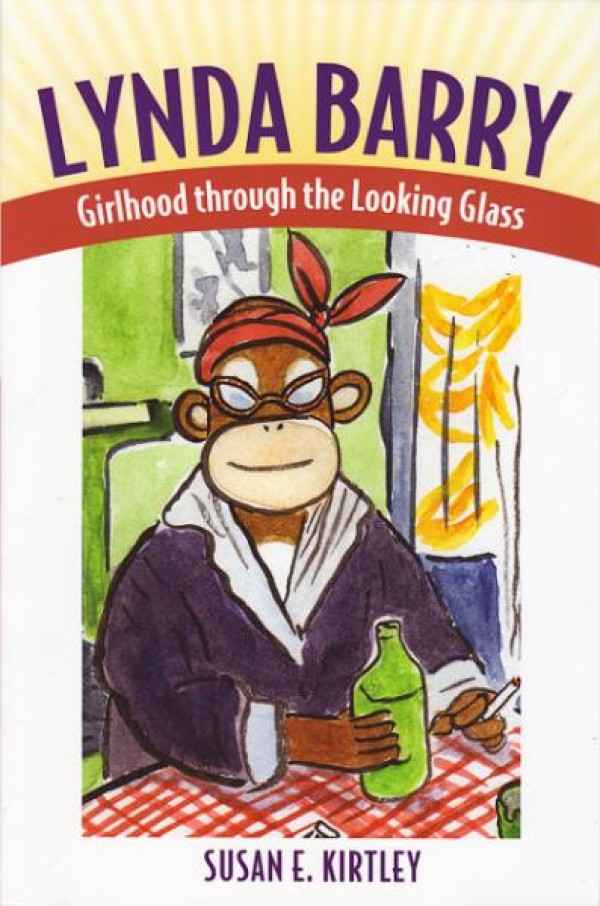

Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum in Columbus, Ohio, in 2013. I knew of her, having watched Kirtley's Eisner Awards win earlier that year for

Lynda Barry: Girlhood Through the Looking Glass in the nascent "best educational/academic publication" category. As a non-academic catching up to her work and watching her present over the last 18 months or so, I am struck by how honestly and thoroughly engaged her reading of the material in question seems to be. More than most, Kirtley seems willing to accept what the works she studies have to say for themselves. I look forward to future books, and hope for several. I was further intrigued that Kirtley was at the center of the

Comic Studies Society meetings at

ICAF this year. That's a newly-launched group for the support of those studying the comics form. I thought it might be a good time to interview. Happily, she agreed. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: Susan, I've read in a couple of profiles you had an interest in comics as a kid that endured and then shifted in focus when you got to college age. I'm interest in that shift, because it's one every young reader makes. What were some of the big titles for you, meaningful creators or works to discover, as you were finding works that interested you in college and beyond? Did you see it on a continuity with your older interest in mainstream comics?

SUSAN KIRTLEY: I am a lifelong reader of comics, and I am sure that I've told you the story of starting to read comics in elementary school because I was told, in no uncertain terms, "girls don't read comics." In those early days I read what I could find on the spinner racks at the supermarket, primarily superheroes, but as I got older and became more mobile and independent I entered that magical place -- the comic book shop. As a teenager I started investigating darker, more mature titles. I loved

Tank Girl and

Preacher and became fascinated with

Dark Horse titles like

Ghost,

Barb Wire,

Grendel and

Concrete. In college I discovered the Alternative and Underground movement, yet through all of this I still loved the superhero titles.

I am, by nature, a voracious and catholic reader of all sorts of texts, regardless of whether the narrative is primarily text-based or a graphic narrative. I subscribe to the

New Yorker and

Entertainment Weekly. In sixth grade I got a "Great Works of Shakespeare" anthology and read the giant tome entirely, while at the same time devouring

Judy Blume and

Madeline L'Engle. I've been devoted to comics for a long time, and as I've grown older and read more that passion and appreciation has only grown as I've discovered the depth and diversity of comic art.

SPURGEON: Was comics always going to be the end result of what you studied? Because most of the papers listed under your bio, they don't seem to have comics connection at all, and in one interview you actually said you worked outside of academia, in television. Is there any danger at all for an academic to limit themselves to one medium, one area of study like that?

KIRTLEY:

SPURGEON: Was comics always going to be the end result of what you studied? Because most of the papers listed under your bio, they don't seem to have comics connection at all, and in one interview you actually said you worked outside of academia, in television. Is there any danger at all for an academic to limit themselves to one medium, one area of study like that?

KIRTLEY: Honestly, I never thought I'd be lucky enough to study comics as a career. As I said before I've been reading comics for an awfully long time, but it wasn't until fairly recently that I was able to incorporate comic art into my scholarly work. Academia encourages us to focus narrowly, becoming an expert in a very small area. This is wonderful in that it allows us to think deeply and look closely, yet given my somewhat itinerant personality I find I am drawn to many areas of inquiry.

After graduating with my undergraduate degree I worked for a little while at

PBS in the documentary department, which allowed me to indulge my fascination with the interplay of text and image as I worked with written script and filmed footage. As time passed, I noticed huge budget cuts at PBS; they were replacing my senior colleagues with cheap, uninsured recent college graduates -- like me -- and I decided it was time to go back to school. While in graduate school I studied medieval women writers, feminist theory, rhetoric and composition, writing and technology, and visual rhetoric, amongst many other things. Some might find my curriculum vitae to be peripatetic since I've published and worked in several areas, but I think it also represents my continuing interests in representing voices and subjects marginalized or underrepresented in academic discourse. For me it is not so strange to examine the wonderful illuminated manuscripts of

Christine de Pisan, the evolving world of writing for the screen, and the unique conventions of comic art.

SPURGEON: What is the study of visual rhetoric? That would seem to apply to comics, or at least the definition of "visual rhetoric" I have in my head, but I honestly have no idea if it does or not. Is there a way to describe what you might uniquely bring to the study of comics, your specific area of study?

KIRTLEY: Visual rhetoric sounds quite fancy, but it is really quite intuitive -- the study of imagery as used in rhetoric. It's a fairly new area of inquiry within the very old field of rhetoric. How are images used to communicate? To persuade? To argue? We can study posters, advertisements, architecture, and, of course, comic art, in an attempt to better understand what the visual imagery conveys. The discipline of visual rhetoric offers a set of tools, a theory and vocabulary, for analyzing and interpreting comics that can provide another way of looking at the form. As someone trained in rhetoric, I find it very useful to bring this lens to my study of comics as a way of analyzing this medium I adore.

SPURGEON: You received an offer to write a book on Lynda Barry based on a lecture you gave -- you were verbally offered a contract right after speaking, if I have the story right. What do you remember about considering that offer? Did you have to make a case for what a book might look like, if only to yourself?

KIRTLEY:

KIRTLEY: I did actually have to submit something in writing to the

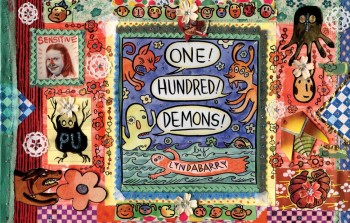

University Press of Mississippi to get a contract for my book, but it was, without a doubt, another very lucky break on my part. I gave a presentation about Lynda Barry's

One Hundred Demons at a conference and had an opportunity to meet the great

Tom Inge just afterward. He is the Series Editor for the Great Comics Artists Series with UPM, and he encouraged me to submit a proposal with the text from my talk. I was nervous because I was primarily trained as a rhetorician and scholar of literature, but Professor Inge sat me down and asked me what comics I liked. I proceeded to monologue for 15 or so minutes about all of my favorite comics, at which point Inge simply stated, "You'll be fine." He explained that many comics scholars come from other fields, but learn as they go. I think he saw my passion for comics and figured I should make the attempt. With his encouragement I sent off the proposal. I knew the subject of the book was important, but I worried whether I should be the one to tell it. I compensated by researching obsessively after receiving the contract, and trying to do my best to honor Barry and her work.

SPURGEON: One compelling through-line in the Barry book is how the fact that she works in so many different media, and to different ends project to project, allows you to isolate recurring elements in her work such as her depiction of childhood, of young girls. Does her facility across several media change the way she works within specific media, though. Is she a different cartoonist for also being a playwright?

KIRTLEY: I do find Barry's proficiency in so many media fascinating, and, I suspect, something of a rarity. Certainly we can see her strengths as a writer in her comics. She is clearly loquacious, cramming a great deal of narrative and speech into each panel, and even considered in isolation, this writing is excellent. However, I think her skills as a visual artist also influence her writing. She used a paintbrush to paint the text of the manuscript that would become

Cruddy, which forced her to slow down and consider the shape and meaning of each word. I think Barry would say that she is focused on rendering the image, and the form it takes (essay, comic, painting) doesn't matter as much as being truthful to that image, but it is quite a gift to be able to create in many media. I, for one, feel lucky to craft a decent sentence, let alone paint or draw an image.

SPURGEON: What do you remember about the interview she gave in support of the book? How did you arrange that? She's very careful about protecting her time considering that so many people want to spend time with her. What is different about the book for her having done that with you.

SPURGEON: What do you remember about the interview she gave in support of the book? How did you arrange that? She's very careful about protecting her time considering that so many people want to spend time with her. What is different about the book for her having done that with you.

KIRTLEY: Throughout the process of writing the book I was extremely cautious of maintaining a good working relationship with Lynda Barry. I reached out to her through her agent, and set up an interview at the

Omega Institute in Rhinebeck, New York. She was teaching a weeklong "Writing the Unthinkable" workshop, and I was able to attend and to conduct an interview with her. She was also gracious about providing the cover art and answering additional questions. However, I was careful not to ask too much of her. She is understandably protective of her time and her privacy, and I was very aware of that.

I felt incredibly privileged to conduct the interview. It was an extremely hot day in July, and the two of us sat in lounge chairs in the forest, surrounded by ancient trees, acrobatic squirrels, and the buzzing drone of insects. As I was getting set up I was sweating profusely and fiddling with a clunky, old school recorder; I'm sure nothing I did inspired confidence in my abilities. But as we talked and I began sharing about my own life, I think we both began to relax. At one point she turned to me and said, "You're alright," and I felt our conversation take another turn. We sat and chatted for several hours, and my list of questions was forgotten, but when I looked back at them later I realized we'd covered them all and more. Lynda Barry was obviously the heart of the book, and she was incredibly kind to give so generously of her time. In early drafts of the book there were huge chunks of transcripts of Lynda Barry just talking. The editors kept pushing me to cut back, but she's just so good!

SPURGEON: Was there a specific one of Barry's texts you found more difficult than the others? You write with a great deal of confidence, which gives this really nice energy as you unpack these ideas, like how conclusions regarding certain protagonists in her fiction may have led Barry to some of the methods she uses in teaching. I just wondered if all the chapters went that smoothly, or if there was something with which you struggled.

KIRTLEY:

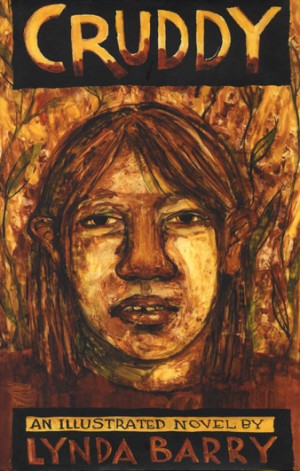

KIRTLEY: As a reader, I have a hard time with

Cruddy. You would think that as someone trained to study text-based novels I would find

Cruddy the easiest work to analyze; it is such a rich text to unpack. The paratext alone is fascinating. However, I find it to be such a raw, visceral piece that it can be incredibly painful to read. That's a testament to the quality of the work, but it's a very draining text to spend time with, at least for me.

SPURGEON: Was winning the Eisner important to the book? Was it important to you? What do you remember about that night now? Charles Hatfield told me that it was indeed a really big deal for an awards program to honor academic work in the Eisners have with his book and your book.

KIRTLEY: I am so glad that the Eisners decided to include a category for Best Educational/Academic publication. I think the category represents the great comics scholarship that is being done and demonstrates that academic inquiry can serve to illuminate and elucidate comic art.

I worked very hard on my book so I was thrilled to be nominated for the award, but once I saw the other nominees I was floored. These are scholars I thoroughly respect, and frankly, I'm in awe of them. To be included in that company is astounding. I went to the Eisner Awards never have attended a

San Diego Comic-Con before, and to say I was overwhelmed was an understatement. I attended convinced that I would never win, but knowing that this was my chance to be in a room full of the most talented, innovative people working in comics today. When my book received the award I, for lack of a better turn of phrase, freaked out. I remember trying to run -- not walk -- to the front of the room like a rat in a maze, but being unable to find my way through the tables. It was not a particularly dignified moment, but as I was ushered off the stage my friend and mentor

Charles Hatfield and his lovely wife Michele were there to prop me up. Suffice it to say, the award was a lovely and unexpected honor, one that I think speaks to Barry's influence and importance.

SPURGEON: What led you to want to go back and serve as a judge? That just happened, like the day we're talking. That's a lot of comics to read, Susan.

KIRTLEY: After attending the Eisner Awards at Comic-Con and experiencing this grand celebration of comics, I was eager to contribute in any way I could. I consider it an honor and a great privilege to help select the Eisner nominees. I know this is a cliché, but it's a dream come true. Furthermore, it's so much fun -- so far. You should probably ask me again in a few months. And yes, it's a lot of comics. I'm putting everything else on hold and holing up in my homemade Fortress of Solitude for the next few months, but what a great excuse to read comics!

SPURGEON: I love the approach with the Lynn Johnston material. Can you just talk in broad terms about the period you're covering with this new inquiry, what the basic parameters of your approach invovled? Speaking of which, am I to take it that this period has since ended on that feature, that this something you can study with a beginning and an end?

SPURGEON: I love the approach with the Lynn Johnston material. Can you just talk in broad terms about the period you're covering with this new inquiry, what the basic parameters of your approach invovled? Speaking of which, am I to take it that this period has since ended on that feature, that this something you can study with a beginning and an end?

KIRTLEY: I'm interested in studying several comic strips created by women that all began shortly after 1975 and all ended around 2010:

Cathy Guisewite's Cathy (1976-2010),

Lynn Johnston's For Better or For Worse (1979-2008), Lynda Barry's

Ernie Pook's Comeek (1979-2008) and

Alison Bechdel's Dykes to Watch Out For (1983-2008). I am still very much in the process of studying these comics, but I'm interested in the way that the strips render a rhetoric of domesticity that informed national opinion, simultaneously reinforcing and rejecting popular stereotypes of women, children, and family. The project will explore these strips and the ways in which they posit a complicated, multi-faceted perspective on family and relationships that is both personal and political.

SPURGEON: Is there anything that ties this inquiry into past takes you've had on things like the visual language involved? I don't see as natural a connection here as I do with Lynda Barry.

KIRTLEY: I've done a great deal of work with feminist theory and women writers, which is a theme that certainly recurs in my research interests and probably explains why I'm drawn to looking at the work of these creators. I'm also quite intrigued by the range of visual imagery expressed in the strips, and how it works in concert with the language.

SPURGEON: What does a working academic get out of a weekend like an ICAF? Both ideally and practically. What did you walk away from Columbus having experienced that's useful to you moving forward?

SPURGEON: What does a working academic get out of a weekend like an ICAF? Both ideally and practically. What did you walk away from Columbus having experienced that's useful to you moving forward?

KIRTLEY: I am something of a hermit, so events like ICAF can be challenging for me, but I've made a conscious effort to attend such events and really participate, attending the presentations and engaging with the other presenters because I find it so inspiring. These are folks who are creating exciting, innovative scholarship, and hearing about their work and having the opportunity to ask questions stimulates my thinking. I've also received great feedback on my own work -- suggestions for texts I should read and consider, ideas for connections with other scholars, and queries that spur my thinking. And finally, I've met the best colleagues, friends, and mentors I could imagine. These are people who help with teaching questions, research questions, life questions -- just great people to have a few drinks with and completely geek out.

SPURGEON: One of the underlying themes of this year's ICAF is something that I'm sure has come up multiple times with your work on Johnston: the idea that our knowledge of the personal lives of various comics-makers is something that should be explored, something that should inform us, and academics needn't be afraid to go into these areas in a respectful, curious way. Bart Beaty agitated on behalf of dealing with records of historical fact that way at a couple of panel presentations, even. How do you feel about getting into these areas with your work? What kind of standards do you apply?

KIRTLEY: In my doctoral program I was advised to avoid biographical readings of texts, since we can never know the "real" or "true" author, but only what Foucault would call the "author function," our creation of the idea of the author. Therefore I approach biographical information about creators carefully. In my work I would be cautious about making easy claims that a particular comic artist made a choice as a direct result of an event in his or her personal history. However, when working with artists like Barry and Johnston who reference themselves as artists in the work itself, I think you have to address the creator, or at least that self they present in the work.

SPURGEON: What was your response to Bart Beaty's challenge in his keystone address at ICAF that cartoonists need to be more engaged with neglected area of comics studies? What about his assertion that comics academics could be doing more within their departments to better up their chances of doing things on behalf of comics, on behalf of comics academia. Do you have aspirations in this direction?

KIRTLEY: I am a big fan of Bart's work so I was delighted by his talk. He cited statistical evidence that proved a feeling I've had for some time, that there are large swathes of unexplored areas in comics studies. As someone who loves all sorts of comics, from auteurs to mainstream publishers, I felt affirmed that the work I'm doing is worthwhile, both in my research on comic artists like Lynn Johnston and Cathy Guisewite and in my program building at Portland State, where I'm developing a Comics Studies program. I think if we are to promote comics scholarship and, for that matter, production, we need to lobby for resources and recognition. I'm trying to do that within my own university through program building and in the wider field of scholarship through my work with the Comics Studies Society and the MLA.

SPURGEON: How did you get involved with the Comics Studies Society? And where are you guys right now in terms of its development? What's the next big deadline?

SPURGEON: How did you get involved with the Comics Studies Society? And where are you guys right now in terms of its development? What's the next big deadline?

KIRTLEY: I attended the meeting Charles Hatfield organized at the Festival of Cartoon Art at Ohio State in 2013 to discuss such a society, and I was struck by the excitement of everyone in the room. Those who know me know that I have a bit of a compulsion for organization, thus I took detailed notes on the event and helped suggest some deadlines and procedures for moving forward. Over the summer I worked with Charles Hatfield,

Matt Smith and

Nhora Serrano on bylaws for the group, which we presented at our first official meeting the following November at ICAF, which was also held at Ohio State. Currently, the Executive Committee is working on establishing non-profit status so we can begin admitting members as soon as possible. Once we've tackled the business issues we can begin our mission, "promoting the critical study of comics, improving comics teaching, and engaging in open and ongoing conversations about the comics world."

SPURGEON: How would you describe the necessity for such a group to someone on the outside looking in? Where are you guys right now?

KIRTLEY: The Comics Studies Society bills itself as "the US's first learned society and professional association for comics researchers and teachers," and I believe that such an organization is important for answering Bart Beaty's call and promoting comics scholarship. Academics studying comics come from many different disciplines, which makes the field diverse and exciting, but also difficult to organize. Many scholarly conferences in different disciplines host panels on comics, but this society has the opportunity to bring all of us together.

*****

*

Susan Kirtley Biographical Page

*

Susan Kirtley's book Lynda Barry, Girlhood Through The Looking Glass

*

Comics Studies Society

*****

* photo provided by Kirtley

* from Christine de Pisan, I think

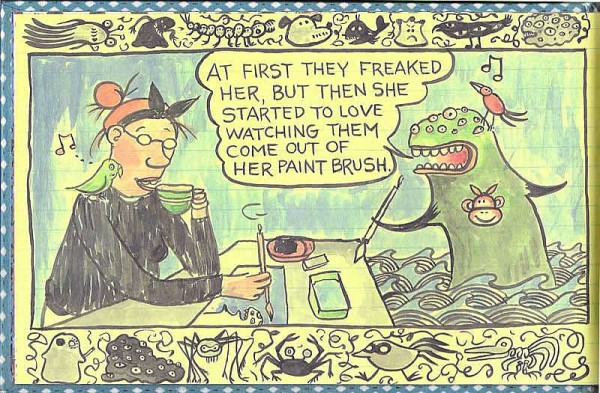

* Lynda Barry's

One Hundred Demons

* Kirtley's book on Barry

* the Barry book that's most difficult for Kirtley to read

* the first strip from the post-conclusion period on

For Better Or For Worse

* ICAF, the every-18-months academic conference, this year hosted by the good folks affiliated with Ohio State

* CSS, the new academics-support group of which Kirtley is a significant part

* one more from

One Hundred Demons, below

*****

*****

*****

posted 12:30 am PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives