November 22, 2014

CR Sunday Interview: Andrew Farago

CR Sunday Interview: Andrew Farago

*****

I've known

Andrew Farago for several years now, long enough I can't remember exactly when we met. He's Curator at

the Cartoon Art Museum in San Francisco, and has authored a variety of comics, ranging from self-directed mini-comics/webcomics series to gigs at

Marvel. Farago is also an effective writer

about comics, so when I saw he was the author of

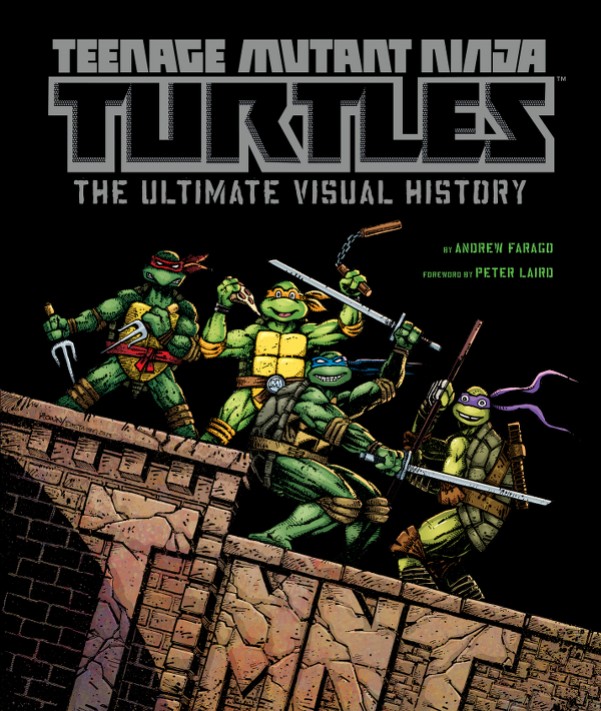

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: The Ultimate Visual Guide I perked up a bit. I think there's a lot of nuts and bolts history being put down in books like this one, which is very elaborately designed and presents to its readers page after page of scans and recreations of objects in the history of the unlikely worldwide comics and licensing hit. I think these books are even more likely to be valuable when someone with the access and doggedness of Farago is providing copy.

The longtime, still-ongoing success of a comic that was at best in my personal top 200 of brand-new series purchased as a comics fan that decade is something that's always baffled me. I thought Farago's book was very sweet in the way it chose to make itself the unlikely story of

Kevin Eastman and

Peter Laird over a version that might have favored the licensing agents and animation producers that took the

Turtles from substantial comics profits to immense real-world, pop-culture impact. The Eastman/Laird story has been a remarkable one, and while in many ways what happened is so very different from what might happen now there are similarities in a number of self-directed page to screen to toy projects of varying magnitudes. I thought I'd take this opportunity to ask Farago all my

Turtles questions and maybe by doing so get at one or two of those broader issues. I'm grateful he humored me. I tweaked a bit for flow. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: I suppose this is a pretty standard question with which to begin things, but do you have a personal history with the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles? Can you describe your personal awareness of and fondness for those comics, those characters?

TOM SPURGEON: I suppose this is a pretty standard question with which to begin things, but do you have a personal history with the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles? Can you describe your personal awareness of and fondness for those comics, those characters?

ANDREW FARAGO: Like millions of other kids who grew up in the 1980s, I learned about the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles when the first animated mini-series aired in syndication. It was right around Christmas break in 1987, and my younger brother and I were hooked as soon as we saw the first commercials advertising the mini-series. We watched every re-airing of that first series, then

the regular series, and again, like millions of other kids, we begged our mom for every single TMNT product we could get.

I scored the second print of the fourth issue at a flea market sometime that year, and was blown away at how much different

the Eastman/ Laird comics were from the TV show. Blood, swearing, gritty artwork... I bought a few more early issues around that time, but the television series was more my speed at 12 years old.

I still have the Turtles action figures we got for Christmas '88, although most of the other stuff we couldn't live without at the time got tossed out over the years.

We went crazy for

the first live action movie when it hit in 1990, and again, like millions of other kids, I moved on to other things after

the second movie hit. Apart from catching the second animated series on TV every once in a while and revisiting the Eastman/Laird comics, I didn't pay much attention to them for a long time after that.

SPURGEON: What about your past, this past as a fan and then, suddenly, not one, made this an easier book for you to write? What made it harder?

SPURGEON: What about your past, this past as a fan and then, suddenly, not one, made this an easier book for you to write? What made it harder?

FARAGO: Obviously I'm biased here, but I think being a lapsed fan was a big help. I have a real fondness for the source material, but being away from it for a period of time gave me just the right amount of distance. Thankfully I'd been a fan during the most prolific period for TV, movies, comics and merchandise, so catching up wasn't quite as daunting as it could have been.

If I hadn't been such a fan in the late '80s, I don't think I'd have committed myself to two years' worth of research and writing. Although if I'd kept up on the Turtles, I could have saved myself months of research and a lot of money at comic conventions.

SPURGEON: [laughs] How was the project presented to you? Were you the primary choice?

FARAGO: Chris Prince, editor at Insight Editions, sent me an e-mail letting me know that they'd gotten the license from Nickelodeon to do a big TMNT history book, and he invited me to send a pitch for a 200-page book. I told him that I'd start with the Eastman and Laird comic, then would follow the property through all of its various incarnations all the way through the latest versions from Nickelodeon, which bought the entire property from Peter Laird in 2009.

I think that a half-dozen writers pitched for this one, but my day job at the Cartoon Art Museum gave me a leg up, since that gives me a lot of access to creative talent and the art collectors who would be providing a lot of the book's imagery. One collector I've worked with a lot over the years owns the complete first issue of

TMNT, and he let us scan every single page of it for the book. None of the other potential writers would have had access to materials like that.

SPURGEON: Were Kevin and Peter involved from the get-go?

FARAGO: Kevin and Peter were on board immediately, although Insight Editions was only able to set me up with Nickelodeon, officially. I had to track Kevin and Peter down on my own, along with all of the other writers, artists, voice actors, animators, puppeteers, rappers, and other creative talent I interviewed for the book.

SPURGEON: Huh.

FARAGO: I spent about two hours on the phone with Kevin midway through my research, and Peter and I traded e-mails for about six months, with him answering every last TMNT question I had in painstaking detail. Getting their full cooperation was an essential part of the book, and I'm incredibly grateful for the help they provided every step of the way.

SPURGEON: Were there restrictions or imperatives that directed the content?

FARAGO: There were almost no restrictions on the book, which was a huge relief compared to some of the corporate-owned properties I've worked on. Nickelodeon had to sign off on everything, and I think their only editorial input came in the chapter about the current Nickelodeon cartoon series, and even that was just clarifying some people's official job titles.

But now that I mention Nickelodeon, I remembered the book's biggest obstacle, which was that so much of the latest live-action movie was completely under wraps, and a lot of it was being reworked as we were going to press. That chapter's a little more vague than I'd have liked, and some of it was factually inaccurate by the time the movie was released. I was able to make adjustments to that chapter with the book's second printing.

SPURGEON: Where does a book like this fit into the wide spectrum of material aimed at Ninja Turtle fans? I have no knowledge of that fandom beyond assuming there is one. Is there a lot of material with this basic level of sophistication that is also fan-oriented?

FARAGO: As someone who's been a dedicated comics fan for most of his life, I don't think I've encountered anything quite like TMNT fandom. There are a number of really dedicated fansites online, weekly podcasts and YouTube shows, review sites, collector groups, fan clubs, meetup groups... so many people who just live and breathe Turtles every day. Two guys who live right in my neighborhood have TMNT tattoos, and every time I see them, they're wearing some piece of Turtles gear I've never seen before. [Spurgeon laughs]

A one-off book can't match that level of intensity or scope, although I've gotten a lot of positive feedback from the really hardcore fans who follow all of the dedicated TMNT sites, and my goal -- and my editor's -- was always to make something that would be accessible to any casual fan of the Turtles. A TMNT blog can run an unedited 10,000-word interview with a storyboard artist, but you're working toward a much different goal with a coffee table book.

For sheer attention to detail, it's hard to top

Peter Laird's blog, which has been updating regularly for more than a decade with really detailed stories about his tenure on the TMNT comics and the 2003-07 animated series that he produced.

SPURGEON: What were a couple of the bigger questions you had going in? What curiosity did you see satisfied?

FARAGO: I was really curious about Eastman and Laird, and tried to make the book as much as possible about their story. I don't know if I believe in Fate, but if these two hadn't lived near each other, didn't have the right mutual contacts, hadn't both grown up on

Jack Kirby comics, hadn't hit it off in person, hadn't spent a slow night at their studio drawing turtles with weapons, hadn't come up with a catchy name for those turtles, hadn't decided to try their hand at making a comic book, hadn't self-published and retained all of the rights to their characters, hadn't sent out a press release that the Associated Press picked up... If any of those things had played out just a little differently, I'd have spent the last two years writing about

Car Wars, the other property that Mark Freedman of

Surge Licensing tried to land the same time he was talking to Eastman and Laird.

The Turtles reached some dizzying heights, but they also hit some real low points in the mid-to-late nineties, and I wanted to get the inside story on that, too, including Peter and Kevin's working relationship. A lot's going to change from the time you're a broke twenty-something artist and when you find yourself running a massive production company that oversees merchandising, films, animation, and publishing.

Over the course of dozens of interviews, I kept waiting to see if anyone had anything bad to say about Kevin or Peter, but it was just one nice thing after another. They seem to have been very generous employers, and were glad to share the wealth during the boom years.

SPURGEON: What was the shape of the archives you had to work with? How much of what you did was tracking down certain things and where did you have to fill in the blanks a bit? Were there particular research challenges here?

SPURGEON: What was the shape of the archives you had to work with? How much of what you did was tracking down certain things and where did you have to fill in the blanks a bit? Were there particular research challenges here?

FARAGO: Fortunately, a lot of key Turtles material, especially the Eastman/Laird comics run, was coming back into print as I was starting my research.

IDW picked up that license after Nickelodeon bought the Turtles, and they've been steadily making a lot of otherwise hard-to-find material available. I had to pick at subsequent volumes of the comics bit by bit, but thankfully

Erik Larsen was able to lend me the complete run of the Turtles' Image Comics series. I look forward to doing a complete cover-to-cover readthrough on anything I missed as IDW completes their TMNT library.

All of the theatrical releases are available on DVD, as are all of the cartoons, and the infamous and long-out-of-print

Coming Out of Their Shells tour is on YouTube, so I was able to at least watch a nice representative sample of everything during my research. I've still got a working Nintendo Entertainment System at home, too, and playing 20-year-old video games was a fun way to unwind after hours of reading.

SPURGEON: Was there stuff specific to the comics history end of things you wish you could have gotten into but didn't because of the interests of the perceived audience?

FARAGO: The book's final word count was in the neighborhood of 40,000 words, and my full manuscript was about 25% longer than that. In order to cover all of the things that were happening with the property simultaneously, I sometimes had to truncate the comics coverage in order to focus on other media. If I could have about eight additional pages in the book, I'd have spent more time talking about the second and fourth volumes of the comics, when

Jim Lawson and Peter Laird were guiding things. I'm hoping to carve out some time soon to do additional interviews with Jim and Peter so that I can run a "lost chapter" online.

Two other bits were left on the cutting room floor, and maybe I'll post those online someday, too. First was a big cross-country motorcycle trip that Peter and several members of

Mirage Studios took from Massachusetts to the

San Diego Comic-Con and back in the summer of 1991. Everyone on the trip had really great stories to tell about it, and I'm hoping that Peter or

Ken Mitchroney or one of the other Mirage alums will do a comic book adaptation of it someday.

I had a full chapter's worth of material on

the Creator's Bill of Rights and the importance of creator ownership and artistic control over your properties, with nice insights from people like Scott McCloud, but we only had so many pages in the book, and it didn't quite fit the overall narrative. I at least managed to make a mention or two of

Peter Laird's Xeric Foundation Grant and its importance to self-publishers.

I could have spent a lot more time talking about the black-and-white publishing boom of the 1980s, but had to settle for making sure that I fit

Dave Sim and

Wendy and Richard Pini into the book. There was probably another full chapter to be had on the dual influences of Jack Kirby and

Frank Miller on Eastman and Laird.

And

Tundra! Can't forget about that. I'd have loved an entire chapter on Tundra and

The Words and Pictures Museum and all of the fun stuff Kevin Eastman did during the Turtles' biggest years. Every cartoonist I know swears that if he had millions of dollars, he'd start a publishing house and give all of his buddies all the money they needed so that they could focus on making comics without having any financial worries or editorial interference. And Kevin Eastman actually did that, and it was a wonderful, amazing, chaotic mess. A few all-time great comics came out of it, at least. Thank Kevin Eastman the next time you read

From Hell or pull a copy of

Understanding Comics off your bookshelf.

SPURGEON: So why do you think that one hit? I was one of the older kids (15) that bought the title cold from a comic book shelf, and I liked it fine, and I bought some issues, but I was never over the moon for it and certainly when it refigured itself to skew younger for other media I had no interest in that beyond the novelty of the background story, that I knew it was these two guys that were managing the enterprise. But the content itself... those first fans, what do you think those first fans responded to?

SPURGEON: So why do you think that one hit? I was one of the older kids (15) that bought the title cold from a comic book shelf, and I liked it fine, and I bought some issues, but I was never over the moon for it and certainly when it refigured itself to skew younger for other media I had no interest in that beyond the novelty of the background story, that I knew it was these two guys that were managing the enterprise. But the content itself... those first fans, what do you think those first fans responded to?

FARAGO: Those first comics by Eastman and Laird were really fun, and there's an energy and enthusiasm to them that makes you gloss right over any number of technical issues with their work. Frank Miller wasn't drawing a monthly

Daredevil comic anymore, Jack Kirby was only doing the occasional book for publishers like

Pacific Comics... doing an adventure comic with an underground sensibility during an era when most mainstream comics were trying their best to look like

John Byrne's Fantastic Four certainly helped their book to stand out, and the black-and-white art with the duo-tone shading really gave the book a distinctive look.

But bringing Fate back into this, if they hadn't come up with that perfect title, Eastman and Laird might still have boxes full of that first issue sitting in their respective garages. The same comic called "Turtle Warriors" or "Mutant Turtles" might have done okay, but something about that four-word combination put it over the top. That title is what got the Associated Press to pick up the story about the publication of their first comic, which helped them to sell out their first printing immediately, which led to an immediately sold-out second printing, which got them thinking about doing a second issue and becoming full-time comic book artists. The same book without that title? Who knows?

And if

TMNT didn't hit, you didn't get the black-and-white boom, with every publisher hoping to create the next

TMNT.

SPURGEON: And without the boom no bust, and a potentially completely different 1990s... Hm. So why even as the context changed for it did the Turtles

SPURGEON: And without the boom no bust, and a potentially completely different 1990s... Hm. So why even as the context changed for it did the Turtles continue

to work, Andrew? Was it just weird enough to be an effective courier for these pretty standard little kid adventure tropes? Was it the fighting? The brotherly friendships? Cartoon or comic book, what is in a successful TMNT story, one that works?

FARAGO: At least since

Star Wars, and probably before that, there always has to be a "biggest thing" for kids at any given time.

Star Wars gave way to

He-Man, and that gave way to

G.I. Joe and

Transformers, and

TMNT jumped in there just as those were starting to fade. The core Eastman and Laird concept is a lot of fun, and you can explain it really quickly -- mutant turtles living in the sewer, and a rat trained them to be ninjas, so that they can fight other mutants and ninjas.

This is where all of those perfect decisions from Eastman and Laird came into play again. They and Mark Freedman threw in with Fred Wolf, who'd produced the hugely successful

DuckTales cartoon for Disney, which coincidentally starred three identical brothers who were identical except for the color of their clothing. Wolf hired David Wise, who'd already been a regular reader of the

TMNT comic book, and who had written a lot of action/comedy/merchandise-driven cartoons already. They figured out which elements of the comic book would resonate with kids, amped up the Turtles' personalities, added pizza and some recurring bad guys into the mix, and it all seems like a no-brainer now.

The theme song, co-written by

Big Bang Theory creator Chuck Lorre and his writing partner Dennis Challen Brown, was another thing that instantly hooked kids. And just like with

Star Wars, the merchandise roll-out was kind of slow, and somehow the timing worked out perfectly. The

TMNT action figures blew off the shelves as soon as they hit stores.

SPURGEON: The timeline seems extraordinarily compressed in terms of going from the comics to the animated TV show and licensing bonanza. Was that atypical for a licensing-heavy cartoon property?

FARAGO: It was a real whirlwind for Eastman and Laird. When they met Mark Freedman, who took on licensing for them, they gave him a month to come shop the Turtles around and if they liked the progress he'd made, they'd keep working with him. He got Playmates on board for the toy license right away, and given the success of properties like G.I. Joe and He-Man, they wisely suggested launching the Turtles on television before rolling out the toy line.

The first comic book was published in the spring of 1984, Freedman came into the picture a couple of years later, and the year after that, the first cartoon was airing on television. By comparison, when Nickelodeon bought the Turtles from Peter Laird in 2009, it took them three years before they started airing their Turtles cartoon and launching their action figure line and merchandising. Angry Birds has been a huge property for almost five years now, and they're aiming for 2016 for a theatrical release, and the big studio superhero movies have staked out another six years' worth of release dates. The first wave of TMNT stuff was really Eastman and Laird flying by the seat of their pants by comparison.

Do I have to say "their respective pants" there? They weren't rich yet, but they had their own pairs of pants.

SPURGEON: Very different pants, too, I'd gather. What's worth revisiting in terms of the later comics, do you think? I'm kind of fascinated by Jim Lawson as a cartoonist, for instance, but I don't know how much work he did on those actual comics, or when he did so.

SPURGEON: Very different pants, too, I'd gather. What's worth revisiting in terms of the later comics, do you think? I'm kind of fascinated by Jim Lawson as a cartoonist, for instance, but I don't know how much work he did on those actual comics, or when he did so.

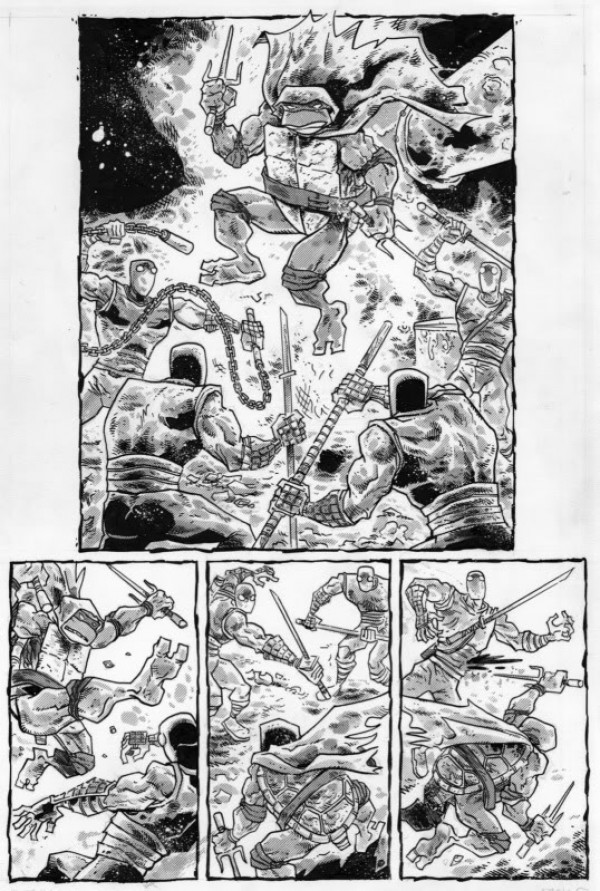

FARAGO: I love Jim Lawson's art, and feel that he's really underrated. Even in my book, unfortunately, since I didn't get to spend nearly enough time talking about the fact that he was actually the most prolific of the TMNT artists, and had a big influence on the Turtles comic books that Mirage published over the years. He joined Mirage early on, with Steve Lavigne and Ryan Brown, assisting Kevin and Peter together, then assisting them individually when they started alternating issues in an effort to keep the book on schedule, then taking on more and more of the art chores as Kevin and Peter's responsibilities to the rest of the TMNT franchise grew. The black-and-white comic book might have wrapped up a lot earlier if not for that core group.

IDW's working their way through the whole Turtles back catalog. My favorites are still the Eastman/Laird collaborations, especially the first 11 issues of the Mirage comic and the four one-shots they did spotlighting the individual turtles. The rest of that first volume is available as full-color trade paperbacks from IDW, and it's a really mixed bag. Lots of one-off stories about the Turtles meeting strange characters and aliens, the Turtles dropping into fantasy settings, really throwing everything at the wall to see what sticks. I'm glad that they were so willing to experiment and let other indie cartoonists cut loose on the Turtles, though. Mark Martin, Richard Corben, Mark Bode... not everything worked, but it was interesting to see them going so far from the mass-media version of the Turtles.

My recommended reading list if you're just starting out would be to read the very first issue from 1984, and if you like that, keep going with

the big TMNT: Ultimate Collection hardcovers from IDW. IDW's current comic series is a fun mix of the original comics and other versions that have come along since. Try the

Change Is Constant trade paperback that kicks off the new run, or maybe

the Northampton trade that Ross Campbell illustrated.

SPURGEON: How much do you think Peter and Kevin were creatures of comics culture and how much were they kind of outside their direct peer group? I would think the control they desired and tried to have was very indicative of 1980s comics-making, as well as their belief in their one big hit.

FARAGO: It's interesting, since their entry into comics was really unlike anyone else's, before or since. Their first convention appearance was to promote

TMNT #1 and to sell their mini-comic,

Gobbledygook, and thanks to advance press, they went into that show knowing that they'd sold through their whole print run of the Turtles comic. But during those years when they were "just" comic book creators, they struck up a lot of friendships with other indie artists, trading comics through the mail, hiring some of those artists to join Mirage Studios or as freelancers on the comic, and a lot of those guys are still friends with Kevin and Peter today. The aforementioned artists who formed the core of Mirage, artists like

Stan Sakai, Ken Mitchroney, and

Dave Garcia.

Kevin and Peter deserve a lot of credit for trying to cut their fellow artists into the Turtles money whenever they could.

Usagi Yojimbo's appearance on the Turtles cartoon and as an action figure brought Stan Sakai's characters in front of an audience that was thousands of times larger than the number of people visiting Direct Market comic shops and conventions.

As far as creative control goes, those two are the textbook example of why artists always need to read their contracts closely, and why you shouldn't sign away ownership or creative control unless you really know what you're getting into. They had any number of opportunities to cash out after that first issue hit, and they could have easily said, "We've sold a lot of comic books, but how far could this thing really go?" But they didn't, thankfully, and I think we're well into our second generation of artists who holds them up as an example of the importance of creator ownership.

They'll both acknowledge that if people like Wendy and Richard Pini and Dave Sim hadn't paved the way, they might not have considered self-publishing to be a viable option. Which is one of those things I love about comics history. If these two hadn't been fans of Jack Kirby's DC books in the '70s, if they hadn't moved on to Frank Miller's comics in the late '70s and early '80s, if

Cerebus and

ElfQuest hadn't earned a living wage for their creators... it's fun to see how all of these disparate elements come together.

SPURGEON: I'm surprised that the Turtles are still around, with as much force as they have -- can you point to one or two creative decisions Peter or other folks made later on, say the 2000s, that have helped keep that whole franchise a living, breathing thing?

SPURGEON: I'm surprised that the Turtles are still around, with as much force as they have -- can you point to one or two creative decisions Peter or other folks made later on, say the 2000s, that have helped keep that whole franchise a living, breathing thing?

FARAGO: When Eastman and Laird signed their TV and toy contracts, Mark Freedman warned them that they'd probably get about two good years out of it before their toys were in the discount bins and they faded into the background. Although that wasn't the case, the peak years couldn't last forever, and by the mid-'90s, the franchise was losing steam. The first live action movie was a blockbuster, the second did pretty well, but

the third didn't come anywhere close to generating the excitement the first film had.

SPURGEON: I took some kids to that third film. It was an empty theater except for us and maybe one other guy, and it seemed like the party was over.

FARAGO: The TV cartoon tried to reinvent itself a couple of times, but its target audience had moved on to the next big thing, which was the

Mighty Morphin' Power Rangers. The whole comic book industry was imploding at the time, which led to the cancellation of the Archie Comics kid-friendly

Turtles comic, and the edgier black and white

TMNT comics weren't finding an audience, either. I think the property was seen as too much of a kid thing by comic shop customers, while kids didn't want the more adult version that didn't look like the TV show.

All of this came to a head with

a live-action show called The Next Mutation, which was actually produced by the same people who were in charge of the Power Rangers. The short version of it is that the producers insisted on including

a female Turtle as part of the team, and Eastman basically agreed to it so that they could keep as many people employed at Mirage as possible. Ratings weren't great, fans hated the show, and Eastman and Laird's relationship was at its most strained, since they'd been on opposite ends of the female turtle argument.

After letting the franchise rest for a bit, apart from Laird and Lawson's

TMNT comic and some merchandising, Laird and Mirage signed on as executive producers for a new

Turtles animated series that was much closer in tone to the original comic books, and Laird took a very active role in that series, something he hadn't done with the original cartoon. I don't recall the exact dates off the top of my head, but if I recall correctly, Laird had bought out part of Eastman's share in the Turtles not long after

The Next Mutation aired (1997-98), and may have bought out the rest of his interest in the Turtles around the time the new animated series started airing as part of the 4Kids Entertainment Saturday morning block.

Which is a roundabout way of saying that the Turtles hit a real low point in the late '90s, but Peter Laird brought things back on track early in the next decade. The new series wasn't the runaway hit that its predecessor had been, but it would have been hard for any cartoon to approach that level of success. The diehard fans embraced it, though, and it introduced yet another new generation of fans to the Turtles. Their ability to reinvent themselves every five years or so has been a big factor in their continued popularity with kids.

SPURGEON: How would you contrast where Laird and Eastman are in terms of how they feel about that whole major first-line-of-obit event of their lives? Are they both happy in terms of how everything worked out, do you think?

FARAGO: Both of them have said to me that they know they'll always be known as the co-creators of the

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, and that's a pretty nice accomplishment no matter how you slice it.

Laird had full ownership of the Turtles when he sold them to Nickelodeon in 2009, and it basically came down to the fact that the Turtles were 25 years old, he was about 50, and I get the impression he didn't want to spend the rest of his life looking at financial spreadsheets and signing off on t-shirt designs. His deal with Nickelodeon allows him to publish his own Turtles comic if he wants, so I don't think he's ruling anything out.

Kevin Eastman has made and lost a couple of fortunes, has bought and sold the 1989 Batmobile and

Heavy Metal Magazine, and I'm sorry there wasn't a documentary crew following him around constantly throughout the 1990s. [Spurgeon laughs] He's absolutely embraced his role as the Turtles' co-creator, doing the work-for-hire thing writing and drawing

TMNT comics for IDW again, so he's come full circle in his career, getting to spend more time drawing comics now than he has in 30 years. He attends about 800 comic book conventions a year and always has a few hundred people waiting in line to meet him.

SPURGEON: He had an amazing line at this year's Heroes Con.

FARAGO: I got to sign books with him at the San Diego Comic-Con in July, and I got to feel like a real rock star for about two hours. Some people just shoved books under Kevin's nose, some shared their life stories, some grown men were shaking in their boots trying to work up the nerve to talk to him... but he made every single person in that line feel like there was nothing he'd rather do in the world than say hello to them and talk about the Turtles. It was one of those great "restore your faith in the power of comics" experiences.

So yeah, as far as my armchair psychology goes, they both seem really happy. Laird gets to stay at home and enjoy life without business meetings, and Eastman still gets the rock star treatment everywhere he goes. I don't think they'd ever trade places with each other, or anybody else, for that matter.

SPURGEON: I forgot to mention this earlier in a serious way. One thing that's very distinctive about this book is its art direction in terms of spotlighting the replication of actual items from the Turtles' publishing and licensing history. Have you ever worked with a book like this before? Are there specific challenges to it? What do you think it adds as an effect?

SPURGEON: I forgot to mention this earlier in a serious way. One thing that's very distinctive about this book is its art direction in terms of spotlighting the replication of actual items from the Turtles' publishing and licensing history. Have you ever worked with a book like this before? Are there specific challenges to it? What do you think it adds as an effect?

FARAGO: My previous "coffee table" history book was

The Looney Tunes Treasury. My editor, Kevin Toyama, and his designers tracked down all of the artwork for the book, created some new art, and I think my only design input was suggesting some of the bonus insert materials and maybe some font recommendations. The publisher established the conceit, which was a history of the Looney Tunes as told by the characters themselves. It was a lot of fun to write, but nearly everyone who'd worked on the classic cartoons had died years ago, so my research was limited to existing Warner Bros. history books and DVDs.

With the Turtles book, I was able to interview dozens of people who'd worked on every aspect of TMNT, and that was a really nice change of pace. I'd never taken on a firsthand research project of this scope before, and I agreed to it before it sunk in just how big a task it was going to be.

I was a lot more involved with the art side of the book this time around, too. Finding original artwork, photographs, and other rarities was part of my contract this time around, and I managed to track down the original art from the first issue, several early covers, preliminary sketches that predated the first issue, some vintage photographs.it was a lot of work wrangling everything, but tracking down artwork has been my full-time job for almost 15 years now.

Insight Editions, my publisher, handled the actual layout and design, although I had a lot more input on that aspect of everything this time around, including recommendations for the bonus inserts. That's one of Insight's specialties, doing these treasury editions with replicas of vintage materials. If you buy one of their music history books, you'll get replica concert tickets and posters, things like that. With the Turtles book, we included a reprint of the first comic book, a copy of Eastman and Laird's press release announcing the launch of the comic, an early business card... Chris Prince, my editor, really pushed for adding inserts as an opportunity to add about 20% more artwork to the book, so that we didn't have to pass up too much of the fun stuff that we found. They're all designed to be removable, too, so you can take them out and store them in the envelope tucked into the book's back cover if you're so inclined.

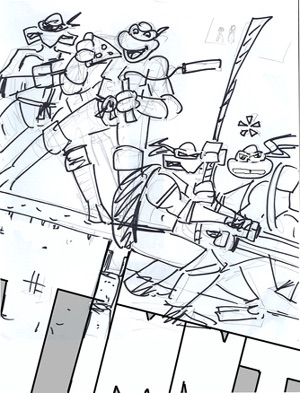

My biggest contribution to the book's art was suggesting that we put Turtles from four different eras on the cover, and that we use the same layout as that iconic first issue of

TMNT from 1984. I drew a few different versions, including one with several dozen additional characters in the background, but we ultimately went with the basic four-Turtle design. We got budget approval to commission new art for the cover, and initially, I lobbied to draw it myself and have Mirage Studios alum

Ryan Brown, who coincidentally lives about 30 minutes away from the town where I grew up, ink it. My editor shot that down right away, so idea number two was to have Ryan pencil and ink the cover himself. Ryan told us he could talk Kevin Eastman into inking it, which was a no-brainer.

Ronda Pattison's been doing a great job as the colorist on IDW's Turtles books, so she was my first choice for the cover, and I was able to talk my editor into that, too. I guess I've picked up a fair number of editorial and art director skills over the years.

SPURGEON: I wanted to ask you a couple of questions about the rest of your work while I still have you. You have a kid at home now, your first. How has that changed the way you look at the vocational aspects of comics? I know some people have been rattled when they have kids about the kinds of opportunities available to them, some even moving into other kinds of work because of that life event. Are you happy in comics?

FARAGO: Having a kid at home has changed everything. About three weeks separates the start of this interview and the last few questions here, and four months into fatherhood, I feel like I'm just finally starting to figure out how to fit a kid, a day job, and side projects into my schedule. It's been a very rewarding, very exhausting, very expensive four months, and the biggest change job-wise is that I'm putting a lot more time and effort into my writing, art, and comics, and I'm talking to a lot more editors these days about potential projects.

Up through the Turtles book, I was content to just take on projects as they've been offered to me, but medical expenses for the baby have taken a toll on our savings, so I've been a lot more proactive about my writing career. I've also been more selective about taking on anything that's going to keep me away from home or that isn't going to contribute to the baby fund. I've turned down a couple of convention trips and have opted out of a few other opportunities that would have left [Farago's wife,

the cartoonist] Shaenon [Garrity] at home alone with the baby or would have monopolized time that I'd rather be spending with my newborn.

Am I happy in comics? I'm still having a great time as the curator at San Francisco's Cartoon Art Museum, and hope to have that job until I hit retirement age. I'm writing books on fun subjects, I've got a cartoonist at home who's drawing exactly the comic that she wants to draw.

I'd love to get some comic book writing jobs again, since I haven't done much of that lately, and my 12-year-old self is still hoping that Marvel will call and ask me to draw

The Amazing Spider-Man for them, but I'm in a good place right now, and so is comics.

SPURGEON: Is "curator" an over-used word? Do you ever bristle when you hear people that aren't in a museum setting or something similar employ that word?

FARAGO: People curate their Netflix queues, they curate their dinner menus, they curate their iTunes playlists... [Spurgeon laughs]

It took most of my life for people to realize that cartoons were cool, so I'm glad the word "curator" is starting to catch on. I'm fine with casual usage of the word, but just like librarians bristle when people call anyone who works at a library a "librarian," I've had people claim curatorial credit by virtue of suggesting an exhibition subject to me or passing along contact information for an artist or a collector. I'm always glad to give credit where credit is due, but there's more to it than just knowing where the art is.

SPURGEON: Who's your least-favorite turtle?

FARAGO: Mark Volman. [Spurgeon laughs]

That's my

Hollywood Squares answer, which come to think of it, is another increasingly dated reference.

It's probably a cheat to say Venus de Milo, the female turtle from

The Next Mutation TV show, so I'll say that Michelangelo would probably be the worst fit for me as a roommate. Empty pizza boxes everywhere, the surfer accent that he somehow picked up in subterranean New York City, and you just know he'd ask you to cover his rent at least a few times a year.

*****

*

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: The Ultimate Visual Guide, Andrew Farago, Insight Editions, hardcover, 9781608871858, 198 pages, 2014, $50.

*

Farago's Personal Site

*

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles At IDW

*****

* cover to the new book

* photo of Farago by Whit Spurgeon, 2012

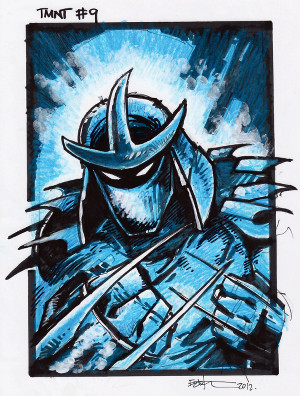

* multiple images from the book, although one or two might be more random imagery from the Turtles' long existence. The contextually important ones are the scene of the turtles all together from that first comic, the full page which features Jim Lawson's work and the rough art from Andrew Farago of what he wanted the cover to look like. That last one was supplied by Farago.

* one more animation-era depiction of the Turtles [below]

*****

*****

*****

posted 8:00 pm PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives