July 27, 2008

CR Sunday Interview: Blake Bell

CR Sunday Interview: Blake Bell

*****

I was happy when

Strange and Stranger: The World of Steve Ditko made its way into bookshops and comic book stores this summer. It was a book I dearly wanted to read, and its author,

Blake Bell, has been working on it for at least as long as this site has been in existence. The end result is an extremely tasteful art book capturing the idiosyncrasies of a surprisingly underrated craftsmen and the most insightful look to date at the motivations that fuel mainstream American comic books' grandest and most mysterious figure. I can't imagine it not being well received. It has already been the subject of a a great deal of first-rank press, so I was delighted that Bell agreed to take some time during his efforts on the book's behalf to interview with this site. He says he answered most of the questions on an airplane taking him into San Diego, and I'm grateful for this extra effort.

*****

TOM SPURGEON: Blake, my first memory of you is the book I Have To Live With This Guy!

I assume you were a comics fan growing up. Can you talk in rough terms about your background and how that's intersected with comics?

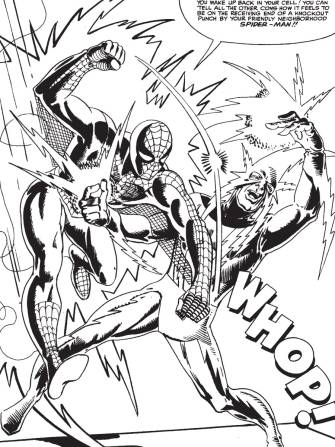

BLAKE BELL: I grew up in Toronto, Canada, born in 1970, reading comics from a very early age. I felt like I had "graduated" into something bigger once I started reading the Ditko/Lee run of

Spider-Man when those Pocket Books came out in the late 1970s. I dove into the "indie/alt" world of comics with

Cerebus in 1987 and never looked back.

SPURGEON: How do you look at the

SPURGEON: How do you look at the I Have to Live With This Guy!

experience now that you've had a few years and are in the midst of another comics-related book cycle. Is there anything you'd change about that book now?

BELL: It was the single greatest learning experience of my life -- besides raising my eight-year-old son, Luke, as a single parent -- in terms of the extraordinary discipline it took to get that book done in what was essentially November 2001 to August 2002. I contacted everyone, interviewed everyone, wrote and designed the book myself, all the while working a 9 to 5 job and being married with a child.

What would I change about the book? Almost everything. I have made a pledge that if March ever has 32 days, I'll re-write and re-design the book. I still stand by the concept as being wholly original and unique, in a field historically dominated by men, and I think I especially delivered on the content piece. We see a side of the artists in question from a perspective no one even bothered to look at. That foundation is what still pleases me about the book.

With my writing and designing skills having improved so dramatically in the past 6 years, it's now almost impossible for me to sit down and read the book. When Will Eisner passed away, I re-wrote the chapter with him and Ann and it was so much better. Far more economical, much more to the point and better organized. The good news is that this has paid off for the Ditko book.

SPURGEON: How cognizant were you of criticism that even with one reverse-gender example, that book propagated a view of defining these mostly formidable women in terms of the creative men in their lives?

BELL: There was a 300+ post thread on The Comics Journal Message Board where some alleged feminist freaked out about the concept... before ever reading the book. Apparently the person had just come from protesting

The Last Temptation of Christ, but that's my only memory of an adverse reaction based on what you're mentioning. I would argue that the book is about "partnership," and not one party living in the other's shadow, especially since comic books don't cast a very long shadow. One could argue that it is the men that are defined by these women because they were mostly the ones holding everything together. And I would love to be in the company of Anne T. Murphy when someone tells her that she was wholly defined by Archie Goodwin. She was, in fact, the fulcrum of the book because it was really tracing and speaking to the social mores of the different eras. By the 1960s, women like Anne were certainly defining themselves career-wise, as did Deni Loubert and Melinda Gebbie, all the way through to Jackie Estrada. Her chapter goes quite a ways before Batton Lash even shows up. Plus Melinda and Eddie Sedarbaum make two "kinda" reverse gender examples, don't they?

SPURGEON: At what point did you first personally encounter Steve Ditko? When did that issue begin to coalesce into the idea of a book?

SPURGEON: At what point did you first personally encounter Steve Ditko? When did that issue begin to coalesce into the idea of a book?

BELL: His co-publisher,

Robin Snyder, was on an internet Ditko discussion group that I joined -- which really started my entry into fandom back in 1997 -- and I kept hounding him to let me start up a web site for them. At the time I was delving into Objectivism through Ditko's work and Rand's novels, so certain behaviors exhibited by me had their camp believing I was someone they could trust not to undermine them with the site. They accepted the offer and it debuted on Independence Day, July 4th, 2001. Up until then and only in the month or two prior had I sent a letter to Ditko and received a reply. We exchanged a few letters during the time the web site was up, but working on the site was all done with Robin.

Unfortunately, there lay a ticking time bomb beneath us all, thanks to the

Comic Book Artist #14 historical fiction piece on Steve and Wally Wood that I had done -- and had vetted through two of Wally's peers -- before the web site offer was accepted. Ditko read it and thought it took too many liberties and objected to being portrayed in such a fashion, so they asked the web site to be pulled down for good. I actually received a check from Robin Snyder dated September 11th, 2001, refunding me for the subscription to his

The Comics fanzine, and they've refused to allow me to buy their product ever since.

Fast forward to November when I was in New York to interview Anne T. Murphy and I went to Ditko's studio to apologize for how the

CBA #14 piece had landed with him. We actually had a great conversation and he said it was "all in the past." That gave me comfort until I was sitting in the Ed Sullivan Theatre later that night, watching the Letterman show live and thought to myself, "Wait a minute, this is the most literal person I've ever met. Maybe he wasn't forgiving me at all, and just pointing out that 'A is A' -- that it was indeed 'all is the past.'" Still, he had shaken my hand upon leaving and put up with me for a good 20 minutes, so I took comfort in that.

That same summer,

TwoMorrows and I had had discussions about doing a Ditko book as part of what is now their "Modern Masters" series, but they recanted when Ditko said to them that he didn't want to participate in such a book. I then sold Gary Groth on the idea at the 2002 San Diego Comic-Con and off we went.

SPURGEON: Am I to understand you selected the art that was used in the book? Can you talk about the art direction process, and how you worked with Greg Sadowski? What were you attempting to do with the way the book was designed in terms of showcasing Ditko's art?

BELL: Yes, I selected each piece and scanned in all but five or six of the over 300 images. The book functions on three levels. First, it's a presentation of the work itself, and for this I made what was probably a daring move. I chose what I thought were the best images out there for each period of his career, and then pursued the best quality reproductions I could find. As much as I like to look at original art, I didn't want to just accept whatever slim pickings there were of Ditko's art on the market -- a lot had been stolen, shredded, lost or horded by Ditko himself -- and run with sub-standard images just to be able to say, "Wow, look at the blue pencil lines on that piece of original art!" And that doesn't even take into account that Ditko is the Mozart of comic-book art -- his pages are extremely clean.

Second, it functions as a critique of the work. True, the best of his work could hang in museums all by themselves, but I continually get frustrated by reading comic-book art books that barely spend a paragraph deconstructing the work. That's not easy to articulate, but I find it fascinating when someone does it with an artist who has something to deconstruct. Third, it functions as a critique of his career: the choices he made and the impact it had on his work -- and ability to get work.

With regards to working with

Fantagraphics, I must say that working with Greg, who copy-edited the book, was fantastically easy. The draft I gave him was 64,000 words and Gary Groth stepped in and said, "We need to get this down to 45K or it ain't gonna be an artbook at all!" Of course, I was trying to con him into giving me 270 pages and a price point of $50, but the economy for that has probably collapsed for good, especially in 2008.

But bless their souls, but they all let me go away and knock it down to 48K and I really feel that I didn't lose a thing that I wanted to say. I was really able to tighten up the writing, knocked out some repetitiveness and some hyperbole, and move some of the art criticism to the captions to help get us to 48K. From there, Greg was very good about staying away from imposing his view of Ditko or the work with regards to any suggestions on editing the text. It was really a question at that point of "tidying things up" with the language or making a point clearer in instances where I couldn't see the forest through the trees, if you will.

Working with

Adam Grano, the designer, was also a dream. I tried to be really proactive and gave him a 35-page document that listed each image by file name, size, caption, etc. and the order I wanted them in each chapter. He went away and laid out a great foundation for the book, and then I went back at them with three pages of changes I wanted to see -- Gary now keeps a defibrillator in the office -- and then Adam was wonderfully accommodating when I went back and forth with him over exactly how I wanted to see it, only stepping in when he thought it would really affect the technical aspects of the design of the book. It was especially gratifying to see Chapter Three come out as it did, because that's my favorite era, and I really had a picture in mind of what I wanted, or at least the limits that I could live with, and we nailed it.

Based on this experience, I really can't complement Gary, Adam and everyone at Fantagraphics enough. I had a vision for this book from 2002, regarding the visuals and the text, and they could have put the hammer down on me in many instances, but they were wonderfully accommodating. I think this is also due to the fact that we all understood what would make a great book and were open to ideas in the regard. Here are two "tit-for-tat" examples:

First, when I got the first design by Adam back, they had really bled a ton of the full pages. They were able to convince me of the value of this, and I was able to convince them to pull back on about 14 of the full bleeds, as I argued that it impacted what I was trying to show with regards to Ditko's ability to take into account all the elements of the page working in unison, rather than just within each panel. They could have told me to go to hell, and say what did I know about designing a book, but they listened, and I did too. Good communication produces a good book. Houda thunk it?

Second, all credit to Adam for coming across as someone who never let ego get in the way of producing a great book. That first design had the "Stretching Things" story at the start of the book sitting on white pages. I looked at it, thought it looked a little dead on the page, so I suggested to him that he should change the background to black and let the blacks on the comic pages blend into the black background, and then make the endnotes have the same black background to book-end that idea. Again, another big suggestion, but we worked together and I know can't even imagine the book without that black opening and closing.

SPURGEON: You mention a favorite period... Is there any period of his work that you feel is under-appreciated? I'm a great fan of his wash work for the Warren magazines, for instance.

SPURGEON: You mention a favorite period... Is there any period of his work that you feel is under-appreciated? I'm a great fan of his wash work for the Warren magazines, for instance.

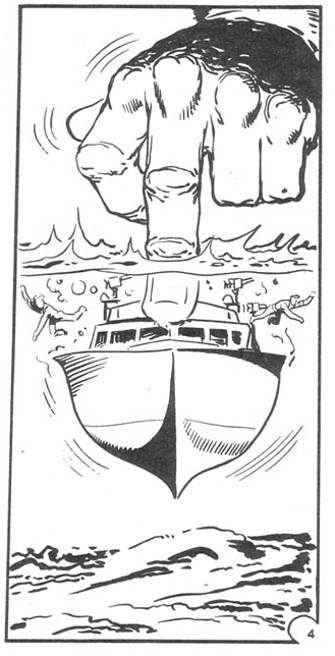

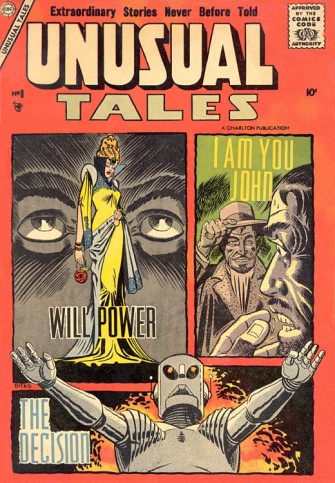

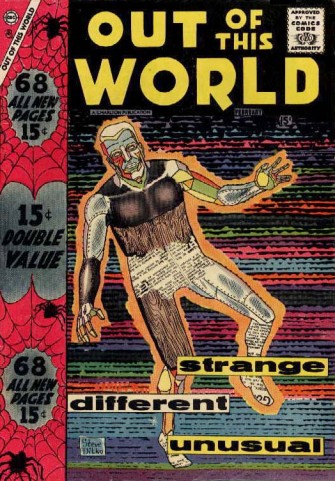

BELL: I love those five-page pre-hero stories that he did for

Marvel, but specifically in 1960-61 where he seemed to be channeling

John Severin's inking style. The work was so tight, so well executed, so brilliantly haunting and so uniquely Ditko in the sense that all the stories seem to focus on these loner characters trying to find their way in a world that doesn't quite understand them. These stood in stark contrast to the Kirby Monster stories that always had some guy trying to impress some girl or the rest of the "collective." And yes, the great thing about an artist like Ditko is everyone can have a favorite "era" like you mention with his Warren work. Between the pre-Code work in 1954, that fantastic Charlton work in 1957, the pre-hero Marvel work,

Spider-Man,

Dr. Strange, Warren,

Mr. A... well, you can see why a book is so deserving.

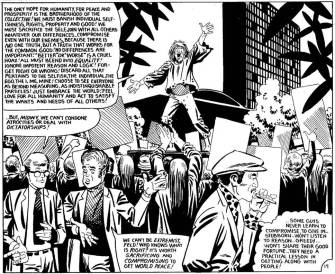

I think Ditko's humor work, on books like

Konga, is under-appreciated. I don't think enough credit is given to just how revolutionary those early

Mr. A stories are. They were so far ahead of their time, and so against the grain of their time.

SPURGEON: Blake, was

SPURGEON: Blake, was Strange and Stranger

always intended for Fantagraphics? I seem to remember it having a life before it ended up there.

BELL: Only for a few seconds was it considered for TwoMorrows and, ironically, had

Brett Warnock had his way,

Top Shelf would have snagged it because I came to the 2002 San Diego Comic-Con with the expressed interest in getting a publisher for the book, and Brett and I discussed it on the Wednesday night, but Gary really ran with it after he saw the response to my Art of Steve Ditko panel at the show, whereas Brett had trouble convincing his partner Chris Staros to venture off their beaten path and focus on the past rather than on the now. You couldn't lose working with either company.

SPURGEON: Why did it take so long to get done?

SPURGEON: Why did it take so long to get done?

BELL: 2004 and 2006 were a wipe out with family- and job-related concerns, plus we tried way too hard to push it out for June 2003 and were really going down the wrong conceptual path, so that didn't help. The book was really rolling in late 2003, the latter half of 2005, and then September 2007 to present.

Putting aside the two lost years mentioned above, I did learn a valuable lesson that all prospective authors should hear. Unless you're one of the guaranteed top sellers in this business, don't expect a publisher to drive the agenda of getting your book done. You have to drive that agenda, and that means not waiting around for responses (but also not badgering -- it's all about the balance) and setting benchmarks and then delivering on them, and finding win/win solutions, rather than just whining about not being paid enough attention. I believe that Gary still wants to do business with me because he knows he can trust that I "get it" and that I'm reasonable and work towards those win/wins, which are all about producing the best book, instead time being consumed by overwrought egos.

SPURGEON: Your biographical information on Ditko's early life is brief, but contains a lot of interesting anecdotal material. What would you have a fan of Ditko's work take away from his early life in terms of a thing or two that might give them insight into the shape and form of his art? What is important to know about Ditko's early life if we're to understand Ditko?

SPURGEON: Your biographical information on Ditko's early life is brief, but contains a lot of interesting anecdotal material. What would you have a fan of Ditko's work take away from his early life in terms of a thing or two that might give them insight into the shape and form of his art? What is important to know about Ditko's early life if we're to understand Ditko?

BELL: His choices of influences from such an early age and his strict devotion to becoming what he set out to be: a comic-book artist that lets the work speak for itself. He clearly has never had an interest in "celebrity" and look at the amount of work that his ethic/belief system has produced. Alan Moore said it best once: that Ditko's DNA is so stamped on all his work that the work tells you more about the man than the man could tell you about his work.

SPURGEON: You repeat the information from a fanzine interview where Stan Lee admits that Dr. Strange was Ditko's idea, which you reinforce with clues from the text that Lee was not as heavily involved -- his touch was missing. You talk some about how Ditko supported the work with research around the city, but what do you think the impetus was in creating that character? Of all the characters he could have contributed to that degree, what was it about Dr. Strange that you think drove Ditko to make that character his creation?

SPURGEON: You repeat the information from a fanzine interview where Stan Lee admits that Dr. Strange was Ditko's idea, which you reinforce with clues from the text that Lee was not as heavily involved -- his touch was missing. You talk some about how Ditko supported the work with research around the city, but what do you think the impetus was in creating that character? Of all the characters he could have contributed to that degree, what was it about Dr. Strange that you think drove Ditko to make that character his creation?

BELL: It's difficult to pin much specific down to Ditko's original impetus because the strip changed so much in scope once Ditko took him into different dimensions (besides the Nightmare world, which was more about going into dreams). What you do see over the course of the strip, as the most likely impetus if there was one, was another loner character, another devout hero, destined to live unacknowledged, saving the world time and time again, living in and between dimensions belonging to neither. Much like Peter Parker's transformation over the course of the strip resembles Ditko's own transformation, I think Dr. Strange really represents how Ditko viewed the world and the ultimate act of a hero: to go unacknowledged but still consistently make positive choices that a hero would without a second thought.

SPURGEON: Can you talk a little bit about Ditko's relationship with Martin Goodman? You suggest that Goodman as well as Stan Lee objected to the growing influence of objectivist principle in Ditko's -- on what basis do you note that Goodman was opposed to this kind of thing seeping in? Did Ditko, like Jack Kirby, have any contact or understanding with Goodman the dissolution of which or failure of same had an effect on his leaving the company?

SPURGEON: Can you talk a little bit about Ditko's relationship with Martin Goodman? You suggest that Goodman as well as Stan Lee objected to the growing influence of objectivist principle in Ditko's -- on what basis do you note that Goodman was opposed to this kind of thing seeping in? Did Ditko, like Jack Kirby, have any contact or understanding with Goodman the dissolution of which or failure of same had an effect on his leaving the company?

BELL: Ditko claims never to have met Goodman in person, but he and others were promised royalties once Marvel took off. When the TV and merchandizing money start to come about, Goodman tried to buy him off with a pay raise. One of the great moments for me in the course of putting the book together was talking to Stan Lee back in 2005. I laid out what others had said about Ditko telling them it was Goodman reneging on promised royalties that was the primary driver of forcing Ditko to leave. This sparked a memory in Stan -- you have to set Stan up for success to get that from him -- about a conversation with Ditko where Stan asked him to come back to do a final

Spider-Man story. Ditko retorted, "Not til Goodman pays me the royalties he owns me!" Stan remembered this because he was perplexed as to why Goodman hadn't kept him in the loop on an issue like this, but Lee remembers Ditko's comment.

As to Goodman's concerns about Ditko's path for the book, we source it in the book so I'll put it another way: as everyone had said about Goodman, including Ditko, "whatever Goodman wanted Goodman got."

Amazing Spider-Man #39 is one of the great "about faces" in all of comics history.

SPURGEON: On the one hand, you talk about Ditko using the fan press as an avenue for publication because of utilitarian reasons -- they were fast, they would accede to his demands for no interference, etc -- and suggest that he may have had nowhere else to go with some of that material, yet later you use a remarkable quote from Ditko where he seems to be suggesting that an appeal to that kind of publishing was that it put his work outside the standard avenues for discussion and examination. Which of those factors do you believe was most important in his working with that kind of publication?

BELL: I think Ditko's idea of "standard avenues" was that there were no avenues for this kind of discussion, and he -- as he always has -- not only harps on publishers for producing such irrational, anti-hero pap, but also goes after the fan for sanctioning it. I think he hoped that he'd find some kind of moral nobility amongst the fan publishers, and I'm sure there was a lot of that, but Ditko also got burned a lot by mainstream and fan publishers. Pretty sad legacy for an artist of his caliber who gave away his most personal work for free; sad that there was no mainstream publishers willing to go to the mat for it, but even sadder is how some fans took advantage of him because they truly were hypocrites and didn't live by the same rational moral code that they pretended to Ditko that they had.

SPURGEON: I think Ditko's later material, even the flat, didactic material he did for fanzines, looks remarkable in a lot of ways, and is generally very boldly designed. Were there an artistic influence on Ditko later in life that pushed him that way? Did he continue to look at and process comics styles the way he might have as a younger man?

SPURGEON: I think Ditko's later material, even the flat, didactic material he did for fanzines, looks remarkable in a lot of ways, and is generally very boldly designed. Were there an artistic influence on Ditko later in life that pushed him that way? Did he continue to look at and process comics styles the way he might have as a younger man?

BELL: I don't see any indication of that. He's never mentioned any artists that he's admired since

[Jerry] Robinson,

[Will] Eisner,

[Mort] Meskin and

[Harvey] Kurtzman, and he's also derided the work of today's creators or sacrificing the hero on the altar of the "anti-hero." I think what pushed him that way later in his career was just a growing desire to push a message that was underpinned with disillusionment of the industry, the fans and the world at large around him.

SPURGEON: Given the way he improved as an artist through the prime of his career, and even accepted bold new ways of doing art later on in some of the not as well-received material, do you think he progressed as a writer at all. If so, how? If not, why?

BELL: I don't see much progression in terms of him writing dialogue. Read a piece from 1969 and another from 1999 and the diction still has the same characteristics. The longer form work, like the two graphic novels from the 1980s,

Static and

The Mocker, show him at his best, but nothing that showed a particular progression, as if he were to have tried a completely new way of presenting characters, or presenting his themes in a particularly new way.

SPURGEON: You argue that one of the reasons Ditko became dissatisfied with some of his publishers was that they failed to meet the standards he felt they should have in presenting his work as he intended it. Yet in the story you tell about his appearance at the convention, that element couldn't have been present, and yet he seemed completely turned off by it in a fashion similar to the way he would walk away from projects or publishers that he felt failed to meet his standards. What was it about that early convention experience that you think convinced Ditko to never go back?

BELL: Beyond just a shyness, I think it goes back to his disinterest in any notion of "celebrity." What was to be gained by going to conventions? He wanted to communicate through his work. Any extracurricular activities only delayed the next work. And then, post-

Spider-Man, he would have been caged by people discussing age-old work, whereas he wanted to present his newer ideas. Let's never forget that he never wanted to be anything else but the best comic-book artist he could be. Everything else could be regard as superfluous.

SPURGEON: Is there any evidence out there that Randians every considered Ditko's work, or how he might be perceived in those circles?

SPURGEON: Is there any evidence out there that Randians every considered Ditko's work, or how he might be perceived in those circles?

BELL: Not a lot of writing about it, except for people citing him as being influenced by Rand. The one instance, though, was when the Rand Estate gave him

carte blanche to do an adaptation of

Atlas Shrugged that Mort Todd had proposed to Marvel. They knew him well enough to trust him with this heavy endeavor, but Ditko rejected it because he didn't want to be responsible for creating one likeness of the famous characters, figuring everyone had their own vision in their heads.

SPURGEON: What had a greater effect on Ditko's life, do you think, his Randian beliefs or this undercurrent that he's generally distant -- cordial, at time, but never married and not super-close to anyone of whom I'm aware -- from humanity? Certainly there are Randians with more of the public evidence of a social life than Ditko's evinced.

BELL: I don't think you can separate the two. Batton Lash once said to me that most people who discover Rand's works don't necessarily go through some heightened epiphany. They instead feel like someone's being able to put down on paper what they've been feeling their whole lives about these issues.

SPURGEON: How do you feel about the criticism leveled at your book from Geoff Boucher at the LA Times

that it's too narrowly focused to be the great book about Steve Ditko that he feels the subject matter demands?

BELL: I may still be too close to this to comment objectively, but then again I did predict before MoCCA that there would be concerns about my book not having enough of "where the bodies are buried." I don't think it would be considered a surprise that some of the mainstream press has tempered their praise of the book with sentiments like "Gee, Ditko was such an oddball, and it's a shame that Blake didn't play this up enough" or "to get into the soul of a man you have to gather anecdotes from peoples' memories of 60 years ago" and "go deep" on whether Ditko is gay, married, did drugs, was left in his own poop by his mom when he was a baby, etc.

I think some people miss the one unique value that comics have over all other mediums, and that is that the creator can take an idea from their head and see it in the public's hands without any filters along the way if they choose. Ditko "the man" is Ditko "the work" and Ditko "the work" is Ditko "the man." It goes back to the "DNA" comment by Moore: everything about Ditko, his beliefs, his personality, his career choices, everything is right there in the work. Sometimes I think I could have just made up a bunch of stuff, or searched far and wide to tap some 80 year-old's memories about a man they barely knew, and people who come in believing, or wanting to believe, certain things about Ditko "the man" would walk away thinking they better understood "the man." It could all be clap-trap, but it wouldn't matter because "inquiring minds want to know," even if it has no basis in fact or reality or could even have anything remotely to do with his work.

If Ditko was/is gay, would that really "enhance" your understanding of his work? I might end up with a sense of pride that we didn't play up his "oddball nature" or wasted reams of paper speculating on the ins and outs of "his soul," as opposed to what we did, which was present and examine the work and how his career choices had an impact on him and his work. Most else strikes me as a little too Kitty Kelley for my tastes. Believe me when I say that I could have run with the zillions of rumors about his private life that have come across my doorstep, and warped that into a "tale of the man," but we worked really hard to "bulletproof" the book, sourcing everything, Gary especially challenging me on every assertion I made in the book, hence the very long and deliberate end notes.

SPURGEON: How has your work been received by the hardcore Ditko fans out there? Have you heard back from any of the major professional fans he had, like Jim Shooter or Frank Miller?

SPURGEON: How has your work been received by the hardcore Ditko fans out there? Have you heard back from any of the major professional fans he had, like Jim Shooter or Frank Miller?

BELL: I'll let you know after the San Diego Comic-Con! Lots of excellent initial feedback about the choice of images, the observations about the work and -- so far -- I haven't received the one reaction I thought I would. I figured there'd be that populist notion about not invading Ditko's private life enough -- "where the bodies are buried" -- but I was more interested/wary of that faction of comic-book fandom that "protects" their heroes at all costs, and would view anything other than a checklist with pictures as a violation of Ditko's privacy. Somebody actually warned, bordering on threatened, me of that if I "went too deep" into his private life. Perhaps the most pride I take from the early reaction is that A) large, mainstream publications consider the writing good enough to even bother reviewing it -- I'm always interested in progressing as a writer; B) that we achieved such a great balance of telling the story and showing the work to more than just the hard-core comic-book fan. Everyone's getting something new out of this and that's extremely satisfying.

SPURGEON: Do you think Ditko will read your book? Would he like it?

BELL: On the one hand, he implies at times that he divorces himself from all of what he views as irrational, whim-based "thinking," but on the other hand, he'll quote articles from the internet, so he definitely has some kind of feeder system going on. He once wrote a fan that he has "no interest in the history of Steve Ditko," but that didn't stop him from attacking Gary and I just based on the previous title and cover image, even though Gary tried to call him to explain the intent. Again, I suspect he'll fall into the camp of "anything other than a checklist with pictures..." He once told a fan that he'd rather read someone who hates his work than someone who presents untruths, so maybe he'll appreciate the critique of his work, but that's likely wishful thinking on my part. If I had ignored any of the choices he made that impacted his life and the work, and just presented a career timeline with images and a critique of the work, I don't know what he'd have to complain about, but that's not all we did, so...

SPURGEON: How far are you on the Bill Everett book? How will it be different than your Ditko book? What's your basic take on his career and its significance?

SPURGEON: How far are you on the Bill Everett book? How will it be different than your Ditko book? What's your basic take on his career and its significance?

BELL: Similarly with the Ditko book, I've been doing "research" on Everett since the late 1990s, so a good framework is in place. The family is on board, so that will present a unique opportunity to "get close to 'the man'" that the

LA Times might crave, but I think the emphasis will be even more on the artwork of Everett. He had a less drama than Ditko in his career, and passed away at the age of 53 which, if that had happened to Ditko, would have knocked a few chapters off that book.

There's still a great story to tell, though, about the creator of the first anti-hero in comics, and Bill's participation in

Marvel Comics #1 and that nascent period in comics. You'll likely see a lot of emphasis on his 1950s horror work. The basic take will be that if he had worked at EC Comics instead of Marvel, he'd likely have been considered the best artist going, and he likely would have had more than one book written about him by now. It's going to be a great book to look at, and it'll capture the zeitgeist of the earliest periods in comic-book history. And I'm donating 10% of my royalties from the book to The Hero Initiative in Bill's name, so hopefully much good will come out of it all.

*****

Strange and Stranger: The World of Steve Ditko, Blake Bell, Fantagraphics, hardcover, 9781560979210, July 2008, $39.99

*****

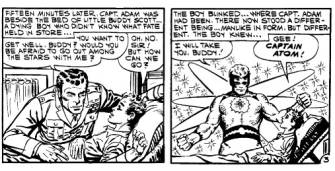

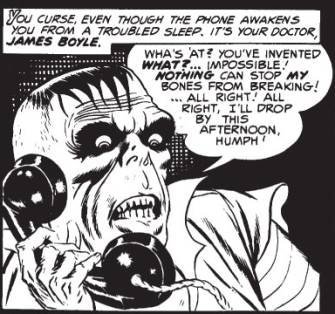

all of the art here is Steve Ditko, with the exception of the cover for I Have To Live With This Guy

. Only a few of the Ditko pieces of art are from Blake's book (the Electro image, the phone image below, the Captain Universe panels, the cover up top and the Mr. A image); my scanner's broke!

*****

*****

*****

posted 8:10 am PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives