August 24, 2013

CR Sunday Interview: Ken Parille

CR Sunday Interview: Ken Parille

*****

Ken Parille is one of the best writers about comics to emerge in years and years and years. The East Carolina University professor can write on a variety of comics-related subjects with an almost serene authority, I think mainly for

the strength of his observations -- the act of seeing being the primary skill of the critic that gets shortest shrift when they're appraised. His

The Daniel Clowes Reader: A Critical Edition Of Ghost World is a marvel. It provides fresh and I think potentially enduring perspective on Clowes' comics work; it makes several forceful distinctions through an egalitarian sense of the critical room rather than forced bluster or clever wordplay. It is a wholly edifying way to revisit and re-experience that work. I strongly recommend it. In lieu of buying it right now just on my say-so or being driven to buy it when you experience the thoughtfulness of Parille's answers below, I hope that you'll maybe at least like

the Facebook page and go look at -- and potentially follow --

the dedicated tumblr site while you make up your mind. I greatly appreciated Parille's time and patience with the following. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: Ken, I apologize for the unimaginative nature of the first few questions, but I'm interested in the answers. If I ever knew anything about you, I've forgotten it. Is there a history of your interaction with comics you could share? I'm primarily intrigued by those points in your life when your interests deepened and/or sharpened and why. I'm always fascinated a bit by how someone over the course of their life ends up writing about this medium.

TOM SPURGEON: Ken, I apologize for the unimaginative nature of the first few questions, but I'm interested in the answers. If I ever knew anything about you, I've forgotten it. Is there a history of your interaction with comics you could share? I'm primarily intrigued by those points in your life when your interests deepened and/or sharpened and why. I'm always fascinated a bit by how someone over the course of their life ends up writing about this medium.

KEN PARILLE: I started as a reader and collector -- at times more one than the other -- of

Marvel and

DC comics. I followed characters and series like the Fantastic Four, Doctor Strange, Hawkman, and Moon Knight, but eventually become more interested in non-superhero comics like

Tower of Shadows,

Chamber of Darkness,

Strange Adventures, and

House of Mystery as well as humor comics like

Swing with Scooter,

Tippy Teen,

The Inferior Five,

Plop!, and

The Adventures of Jerry Lewis. I developed an appreciation for DC and Marvel girls' romance comics that continues. I didn't follow any writers, just artists: I had boxes of

Steranko and

Bill Sienkiewicz.

Things changed dramatically in the mid '80s, during the time known as "The Black and White Explosion," when I discovered

EC,

Disney,

underground, and

alternative comics. I had never seen things like

Daniel Clowes's

Lloyd Llewellyn or

Harvey Pekar's

American Splendor. Pekar's work, so different from superhero/fantasy comics, baffled me, with its lack of action and plots. But there was something that kept me coming back.

Crumb has said that

American Splendor "was so mundane as to be exotic," and I think this was the quality that attracted me.

In the early '90s, I lost interest in current Marvel/DC comics. I remember contemplating a stack of issues and realizing that I had no desire to read any of them. And it was over -- for the time being. I would still buy a few back issues, and the only new issues I would buy were Clowes's

Eightball comics, which came out only two or three times a year. In the late '90s, things changed again. I decided to track down all of Clowes's work and create an online bibliography. And my interest in Clowes lead to a renewed interest in alternative comics, as well as a desire to read all kinds of comics.

SPURGEON: Could you focus on the Dan Clowes aspect of what you do, how your specific interest in his work developed? Was there an initial work of his that struck you? Was there a key work?

SPURGEON: Could you focus on the Dan Clowes aspect of what you do, how your specific interest in his work developed? Was there an initial work of his that struck you? Was there a key work?

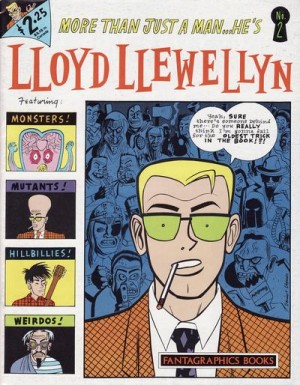

PARILLE: 1986's

Lloyd Llewellyn #2 was my first exposure to Clowes.

The Lloyd Llewellyn comics were so different from anything I'd been reading. I vaguely recognized that the artwork evoked 1950s and '60s advertising art, but because that was popular before my time, my lack of familiarity was part of Lloyd Llewellyn's appeal. The comics were strange, and Clowes's allusions to things I'd never heard of only increased this strangeness. But the series was great because it was funny -- and because it was often very dark, a fact people sometimes forget. Those issues contained violence-soaked comics like "Hound Blood" and "Dementia Praecox" -- and the faces of Clowes's

Lloyd Llewellyn villains are often genuinely frightening. From the beginning, Clowes's work always had this odd synthesis of humor and horror, which plays out in recent graphic novels like

The Death-Ray and

Wilson, though less explicitly now than in earlier comics.

Clowes's art was really appealing; it was far more minimal and angular than what I was used to (though I can recognize connections now I didn't see then, like Clowes's kinship with

Steve Ditko and

Johnny Craig). The panels and pages have a lot of white space, and this openness felt like an antidote to the dense DC/Marvel stuff I had been reading. His art also encouraged me to pay more attention to design than I ever had.

Released after

Llewellyn ended, the early

Eightball issues were important -- I understood the anger toward contemporary culture expressed in comics like "I Love You Tenderly" and "I Hate You Deeply." In his comics, Clowes has a way of tempering his anger, even undermining his own judgments and authority with moments of intense self-criticism. There's a mix of anger, cruelty, sympathy, self-deprecation, comedy, and honesty that, for me sets Clowes's comics apart. Clowes's work confronts very basic, and often very unpleasant attitudes, emotions, and drives, all which he portrays with a ruthless clarity, free from gimmicks. The Rodger Young stories, in particular -- which appear in

The Clowes Reader -- were favorites, with their uncompromising portrayal of adolescence. They also signaled Clowes's turn toward character studies, along with his emergence as a cartoonist who understood awkwardness, alienation, and psychology in profound ways.

SPURGEON: So how did that interest manifest itself first on-line, or in different publications, and then with this book? How does a book like this develop at all? What is the value of such a project to you beyond the engagement with the material it represents?

PARILLE: An important moment was my discovery of

The Comics Journal message board. In the early 2000s, it had a contingent of smart people, from whom I learned a lot. So I began to post regularly and think about how to approach comics criticism. I wanted to be part of a conversation about comics, and the quickest and perhaps best way to do that was online. Then

Todd Hignite, who read my many comments about Clowes on

TCJ, asked me to write a piece on his work for

Comic Art, which he edited, and I wrote my first comics essay on Clowes's

David Boring.

Along with a general interest in comics and Clowes in particular,

The Clowes Reader grows out experience teaching comics for well over a decade, going back to my time as a graduate student. My students have always really enjoyed reading and talking about comics, and we have had many interesting conversations, especially when discussing

Ghost World,

Ice Haven, or

The Death-Ray. Though

The Clowes Reader is not solely a classroom text (as many critical editions are), that use was often on my mind; so I include features like indexes and a glossary, as well as extensive annotations of reference that many college-age students might not know. I wanted the book to speak to different audiences: students, general comics readers, Clowes readers, teachers who wanted a classroom-friendly anthology, and academics interested in comics. Though Clowes is widely appreciated, I edited the book because I think there's so much more to be said about his work; it really stands up to extended analysis from different critical points of view.

SPURGEON: This may be incredibly rudimentary, but I see books that are presented to me as "readers" and I always feel like it's assumed I know what that means, and I'm not sure I do. Is there an accepted meaning for a book like this one, great books in the mini-genre, and do people tend to know what that involves? Is the shape of yours determined by any of those expectations or does it break with them at all?

SPURGEON: This may be incredibly rudimentary, but I see books that are presented to me as "readers" and I always feel like it's assumed I know what that means, and I'm not sure I do. Is there an accepted meaning for a book like this one, great books in the mini-genre, and do people tend to know what that involves? Is the shape of yours determined by any of those expectations or does it break with them at all?

PARILLE: The Clowes Reader comes out of a book tradition in which "reader" is just a synonym for "anthology" -- series like

Viking's Portable Readers, for example. It's also from the "Critical Edition" tradition -- books like Norton editions of literary classics -- and it's related to literature anthologies like the Longman or Heath collections, which include primary texts along with introductory materials and annotations. Yet, because these series differ from one another, we needed a title and subtitle that would tell different audiences what the book was all about -- and it took a lot of back and forth to arrive at the full title. We wanted to use the term "reader" and "critical edition" because these words mean something to some people. But because they mean nothing to others, we used the subtitle to explain the contents: the book is comics, along with essays, interviews, and annotations. Since this kind of collection is somewhat new in comics/comics criticism -- most anthologies are either primary materials (comics) or secondary materials (essays, etc.) -- we needed to be explicit. And since

Ghost World is Clowes's most widely known work and appears in

The Reader, it's in the title, as well.

Though previous anthologies provided models for the book, I wanted to do many things differently. It was important that the collection was smart but not stuffy -- it shouldn't seem too much like a textbook. On a basic level, it needed to be a book that people would enjoy reading and looking at it.

Alvin Buenaventura's design perfectly accomplishes this goal; the look (his choice of fonts and layouts and the colors he selected for certain text and pages) is streamlined and elegant, helping the essays communicate their ideas and giving Clowes's work a setting it deserves.

Literature anthologies typically begin with the editor's introductory essay, but I didn't want to start this way. I thought Clowes should have the first word. So the book begins with a selection of interviews excerpts -- each accompanied by a comic panel or two -- in which Clowes talks about an issue (why he makes comics, his ideas about narrative suspense, etc.) that is crucial to his approach. In this way, Clowes introduces himself. And this section gives readers who might be unfamiliar with his work a series of key ideas to contemplate as they read further.

The Reader ends with Clowes's words, with a lengthy discussion of his creative process. Clowes's ideas about comics and art provide the frame in which everything else appears.

SPURGEON: Talk to me about the general editorial direction of the work, what you wanted in there both comics-wise and text-wise, and how that might have developed since the book's initial conception.

PARILLE:

PARILLE: It took a lot of time to figure out the collection's direction and contents. I first thought it would just be

Ghost World and a few essays about that comic, but quickly realized this was too narrow. So I began to think about how to organize a more comprehensive anthology. I knew that

Ghost World, which is widely read and often taught, would be key. Then I thought of balancing Clowes's 1990s female coming-of-age narrative with the Rodger Young stories, in which a male comes of age in the 1970s. This lead to a three-part structure: 1. Girls and Adolescence; 2. Boys, Adolescence, and Post-Adolescence; 3. Art, Artists, Readers, and Critics. These sections are preceded by an introductory section with interview excerpts, an aesthetic biography, and a general introduction. Section 3 is followed by a brief coda with a chronology of Clowes's life/career and a "For Further Reading" section.

As far as organization, it was crucial that the book alternate between comics and critical materials, and that within the essays, text and images would be carefully integrated -- and Alvin's design does that. I also wanted a diversity of secondary materials: full interviews; interview expects; a piece on Clowes's children's literature precursors; a short feature on Clowes's revisions of character faces (how he changes them from comic to graphic novel); full lyrics to songs that Enid listens to and sings; excerpts from a zine mentioned in

Ghost World; and more. When I couldn't find an essay on a topic I thought should be included, I asked someone to write it. I also thought it would be helpful if

Ghost World, a comic more visually and thematically dense than some might recognize, had an index; so I created one with entries for key themes, words, phrases, and objects.

Since Clowes's comics come from so many different artistic and social perspectives, I include essays that employ distinct critical approaches: personal narrative, literary theory, close reading, historical context, psychoanalytic, etc. In order to addresses a wide readership, I selected writers who are smart and write accessible prose. In unexpected ways, many recurring issues tie the essays together: gender, adolescence, music, punk, grunge/gen x/the '90s, Clowes's aesthetics, urban environments, etc. . . . The essays present readers with an expanded sense of what Clowes is about and offer new ways to appreciate his work.

SPURGEON: You mention the design, and that it does what you want it to… how involved were you in that aspect of the book? Did you communicate to Alvin what you wanted, and if so, how did that communication work? Is there a specific example of a design flourish with which you're particularly happy?

SPURGEON: You mention the design, and that it does what you want it to… how involved were you in that aspect of the book? Did you communicate to Alvin what you wanted, and if so, how did that communication work? Is there a specific example of a design flourish with which you're particularly happy?

PARILLE: Alvin would run pages by me and

Eric Reynolds -- the book's editor at

Fantagraphics -- and I commented on a few placement, layout, and image issues. Together we decided on some of the formats, but the overall look is the result of Alvin's sensibility. Sometimes I wanted a page to be set up one way, but he had a different idea -- and he was right. And when he suggested alternate images for the essays, we went with his because they worked.

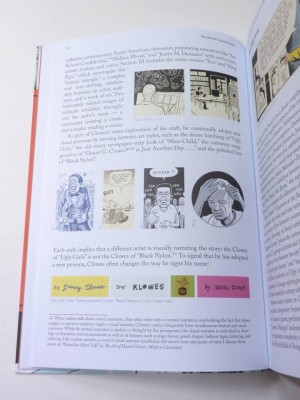

I'm really happy with the color and fonts for section titles, essay titles, and author credits, as well as the use of light blue pages to distinguish sections in list form (such as the Ghost World index, the cartooning glossary, and chronology of Clowes's career) from the rest of the book. For me, these elements signal the collection's approachable tone and straightforward organization. And the cover, which I had almost nothing to do with, is great.

SPURGEON: You seem unwaveringly confident that Clowes work is substantive in a way that flatters this multi-pronged approach. Two questions. First, do you know how comfortable Dan is with his work being explored so thoroughly, and in this fashion? Does the author's perspective in that way matter? Second, or I guess, third, do you feel like taking such an ambitious approach brought with it certain conclusions about the material just for the effort of it? I mean, this is probably a terrible example, but I know when I sit through some academic presentations I don't really get the sense they're reading the same material I am. Usually this is some pretty dull material, and Clowes' isn't, but I wonder if you worry at all about assuming something about the work just by this sort of rigor?

PARILLE: I think that Clowes trusted me and recognized that I'm invested in thinking and writing about comics. We needed to get his permission to do the book, but then he left it up to me to make all decisions about the contents. In interviews, he'll say that interpretation is best left to readers. When asked about a specific scene or panel in one of his comics, he'll sometimes say that, while he has his own ideas about what's going on, he'd prefer that readers make up their own minds. So I think he's open to his work being interpreted in the ways it is in

The Reader.

The perspective of any author I write about typically matters to me. In a way, the frequently rejected notion of "author intention" is often on my mind as I write. This doesn't mean that it constrains what I say, only that for me the process of writing about/ interpreting a comic is usually (though not always) about trying to understand it from a somewhat sympathetic perspective -- each comic is a potentially complex extension of the person or people who created it. Even though a cartoonist might feel that my interpretation is misguided or wrong, I hope that in some way my analysis aligns with the work. This is a vague goal, and I'm sure I often don't meet it.

In

The Reader I discuss Clowes's "Black Nylon" from a psychoanalytical perspective, not just because I like that way of reading, but because the comic is about a troubled superhero who undergoes psychoanalysis. The story is dense and carefully organized, and using a Freudian approach seemed like a good way to explore a complicated comic on its own terms. I have no problem with anyone making assumptions about a comic's meanings or the cartoonist's intentions if those assumptions come from careful engagement with the comic.

You mention sitting "through some academic presentations" and not getting "the sense they're reading the same material" as you are. The feeling that someone's interpretation shares nothing with yours can be frustrating, particularly when he or she is discussing a work you like. Yet interpretations that come from a new or different perspective can be helpful. When I selected the book's writers, I wanted people who were careful interpreters of art, culture, and Clowes. I'd hope that if someone reads one of the essays and thinks, "I didn't get anything like that out of the comic," they'll consider their response as potentially a good thing, acknowledging new ways of approaching the comic.

The collection has been described as "readable" and "accessible," and again, that's one of the goals, especially given that some people associate critical analysis with impenetrability. You're right when you say there's nothing dull about Clowes's work, and so the last thing we wanted was dull, anything-but-readable discussions. The collection's writers avoid this by communicating their excitement about Clowes's work and offering sophisticated analysis. For this kind of book, I think you need writers who merge these two qualities.

SPURGEON: To expand on that last notion, what were your worries going into the work? Can you describe a specific problem that came up and how you solved it? You mention that you wanted certain approaches and when you didn't find them you went out and got them, which is very Steve McQueen, and lot less agonizing than I think most people find putting together a book. What, if any, were the crucial moments for how this work came together?

SPURGEON: To expand on that last notion, what were your worries going into the work? Can you describe a specific problem that came up and how you solved it? You mention that you wanted certain approaches and when you didn't find them you went out and got them, which is very Steve McQueen, and lot less agonizing than I think most people find putting together a book. What, if any, were the crucial moments for how this work came together?

PARILLE: I wondered a lot about which comics I should include. I wanted the book to display Clowes's wide range, especially in terms of visual style, tone, and genre -- few cartoonists work in as many genres as he does, including the realist short story, coming-of-age fiction, cultural criticism, superhero and detective fiction, autobiography, semi-autobiography, newspaper-style comic strip, etc. And I had some difficulty making final decisions, a problem that was partially solved by deciding on the three-part structure I referred to earlier. Some comics fit this structure better than others, and using it as a content guide helped me narrow my options. This focus also helps

The Reader tell a series of larger narratives about Clowes's work as a whole, involving issues of adolescence and post-adolescence, Gen X, the 1990s, advertising, superheroes, the relationship between alternative and corporate comics, etc. . . .

Section 3 also helps with this because it's about Clowes's aesthetics.

The Reader's introductions and essays offer numerous ways to approach his comics, and the comics in this section do the same by presenting Clowes's theories about important topics such as comic books, cartooning, style, autobiography, beauty and ugliness, the cartoonist-reader relationship, critics and criticism, and interpretation. All of his comics, not just those in this book, can be interpreted in relation to ideas that he discusses and dramatizes in this section's comics and

Modern Cartoonist, Clowes's prose manifesto about comic books and cartooning.

The crucial moments are too boring to recount in any detail, but they were key nonetheless: getting the permission required to reprint the cartoons, poems, song lyrics, and essays, and getting the writers I wanted in the book to agree to contribute essays. All of this took a lot of time, and there was a real sense of relief when an email said "yes."

SPURGEON: Can you talk about you used your own writing? I thought that was kind of interesting that there were a number of pieces from you in the book. Was that a matter of you following your own curiosity regarding Clowes' work, or were you used to kind of fill in areas of inquiry where you couldn't find a different piece.

PARILLE: It was both a matter of following my curiosity and writing about topics that hadn't been covered -- or at least hadn't been written about in a way that worked for this book. For example, midway through the project I was thinking about the prominent role advertising plays in Clowes's 1990s comics and how it begins to change in the post-1998 work. His use of signs, billboards, logos, TV commercials, etc. is interesting because it brings up issues that reoccur throughout his comics: capitalism and consumption, the media, insults, the power of images, and Clowes's longstanding fascination with certain kinds of classic product mascots, which often have a near-magical significance in his comics, such as the "Mr. Jones" character/mascot/icon that haunts his first graphic novel,

Like a Velvet Glove Cast in Iron. I didn't search for a piece on advertising because, as I thought about it, I developed a specific idea about the format I wanted it to take: rather than a traditional analytical essay organized around a thesis, I imagined a chronological series of images from his comics and commercial work accompanied by some commentary. Clowes's art would be the focus, and the text would be secondary to the story told by the images.

I thought the collection's overall readability would be helped by having mostly medium-length pieces, not long essays. In part as a result of writing for and reading online sites, I generally prefer shorter pieces, and would guess that many people do as well. Since I needed essays that were relevant to the book's comics, I quickly realized that finding pre-existing pieces of the right length would be difficult.

SPURGEON: Can you talk about specifically how one or two of the essays might have been modified for publication in the

SPURGEON: Can you talk about specifically how one or two of the essays might have been modified for publication in the Reader

?

PARILLE: Pam's essay on

Ghost World, which first appeared in a collection titled

Popular Ghosts: The Haunted Spaces of Everyday Culture, also looked at connections between adolescence and ghostliness in a number of recent films. This material was great, but didn't fit with the volume's focus. So I suggested some edits and a few other scenes she could talk about. We made the changes and were done. The other pieces were edited for consistency in terms of the style sheet, and that's about it.

SPURGEON: You've talked about how you began and ended the book, but is there a key essay in there, or a couple do you think? Reading the book it seemed to me like the Glenn interview and the Melander-Dayton and Thurschwell essays constituted a kind of representative reading of the book entire, like I could let someone read those three and have an idea of what the book was like. How carefully did the curate the middle sections, and to what effect?

PARILLE: You're right that those three pieces could be seen as representative, and I think that's true of many groups, such as one represented by Scott Saul (on the Rodger Young stories), Josh Glenn (on "Original Gen X"), and Darcy Sullivan (on Clowes's creative process). Both of these groups begin to get at the volume's diverse approach to criticism, which includes personal narrative, literary theory, close reading (a story / a line of dialogue), scene-by-scene analysis, contextual (biographical, artistic, and philosophical), interview, etc. Though the book is divided into three thematic sections, I conceived of the pieces as a single group. In this way, no essay or section is key for me; it's really about the interplay between the essays' methods. I thought that constantly moving from one approach to another would keep the writing interesting and give readers unfamiliar with comics criticism a wide sample of the ways comics could be interpreted.

SPURGEON: What essay is furthest removed from your own view of Clowes? Was there work you considered and then on which you took a pass because you just couldn't find a level of agreement with the piece's conclusions? Is it important at all that anyone find totally agreement with the works in a book like this?

PARILLE: Writers like Adele, Kaya, and Josh, for example, approach Clowes's comics in ways that I don't. I couldn't write pieces like theirs because they have knowledge and personal experiences I lack. But that's one of the reasons why I'm happy their pieces are in the book. Though I agree with most of what the writers say, for me it's not really about agreement or disagreement; when one of the writers makes an interpretive claim I disagree with, that's fine. The essays are smart, well-written, and shine considerable light on Clowes's work, and that's what matters. I've certainly read pieces on Clowes that I disagree with, but I didn't consider them for many different reasons, the primary one being that they didn't help readers understand his comics in a new or interesting way.

In my essay on "Black Nylon," I offer some interpretations completely at odds with each other; the comic provides evidence for mutually contradictory readings. Sometimes I see "Black Nylon" as a serious exploration of Freudian theory applied to superheroes, other times as a farce that makes Freud's ideas seem comical by taking them to an extreme, and sometimes as a mix of both. Since I often disagree with myself, I fully expect that readers will disagree with some of the book's claims and observations.

SPURGEON: Can you talk a bit about the notion expressed that Clowes picks a style according to how he wants to express a certain story? How much of that is a feeling-out process, and how much of that is deliberately selected, do you think, on Clowes' part?

SPURGEON: Can you talk a bit about the notion expressed that Clowes picks a style according to how he wants to express a certain story? How much of that is a feeling-out process, and how much of that is deliberately selected, do you think, on Clowes' part?

PARILLE: Clowes seems very intuitive in this way. I'd guess that form and content generally originate together. Yet, after the fact, readers can see reasons why the content works particularly well with the art style; it seems as if the style must have been consciously chosen as the best form for the comic, even if it wasn't. A good example might be "Ugly Girls." The dense crosshatching and compositions seem very appropriate to a story that shows the influence of R. Crumb and his ideas about beauty, ugliness, popular culture, and self-critique: was Clowes (who refers to himself as "D. Clowes" in the comic's dialogue) thinking about R. Crumb explicitly? Or was he channeling aspects of Crumb's style unconsciously? Either way, this comic, like Clowes's comics in general, reveal his constant exploration of style. His work displays many artistic personas embedded in distinct drawing styles. You can see this just by flipping though the collection's comics and comparing opening panels:

Ghost World is very different from "You"; both of these are unlike "Man-Child"; and none of these look like "King Ego."

SPURGEON: Does Clowes's own admission that these comics are sort of amazingly and relentlessly self-revelatory, even the ones that he thought weren't, change the way we should view his work? That seems to present a greater through-line, a relationship between the works, but it also seems like maybe it presents the danger of a thematic sameness. A lot of his work does seems to be an embryonic version of a later one -- I don't know if you'd agree with me that he sometimes works like that or not?

PARILLE:

PARILLE: In the volume I look at the early origins of this personal aspect when I talk about the power comics had for him as child -- the way he would react (often with disturbing intensity) to a comic's images as if they were reality (not a representation), and the way he intuitively interpreted comics in relation to his family life. Reading autobiographical comics in

The Reader like "Introduction" (a never-before-reprinted strip about Clowes's life-long relationship with comics), semi-autobiography like "The Party," and the collection's biographical material can add a compelling layer of meaning to the comics if we think, for example, about the way that a comic like "Just Another Day" connects to his own concerns about truth-telling and autobiographical comics. At the same time, of course, appreciating the comics requires no biographical knowledge -- and we never quite know what they reveal to Clowes about himself and his inner life. In his case, I don't see these comics' personal nature leading to any danger of thematic sameness. While some of his stories arise out of similar biographical sources, they typically employ very different drawing styles and formal organization.

I think you're right that some of his work sets the stage for later comics. For example, you can see the way "Battlin' American" (1987) leads to "Black Nylon" (1997), which sets up

The Death-Ray (2004/2011). These three comics deal with emotionally troubled superheroes (and Clowes drew superheroes and read superhero comics when young), but each uses a distinct approach to narration and form and has a specific tone. In Clowes's work especially, reading a later comic in relation to an earlier one always yields interesting insights because each does something new with the interplay of form, content, and narration. This gets at one reason why Clowes's comics and graphic novels work well in the classroom; they're very accessible as narratives and very innovative as comics.

SPURGEON: Do you see gradations in the severity of the humor between works? I know that there's a notion expressed in one of the interviews that to call early works funny and later works more serious is bad critical thought, but surely there are differences in tone and approach -- there are works that are more bluntly, more directly comedic than others. How does tone work for Clowes, how is that part of the language he uses to express what he wishes to express in certain stories?

PARILLE: These questions bring up one of the most interesting -- and nearly impossible to describe -- aspects of Clowes's work: the nature of its constantly shifting tones. The collection includes "Wallace Wood," a strip that, as a eulogy for one of Clowes's main influences, is appropriately absent of humor. "You" is also not funny; rather it reflects on the relationship between cartoonist and reader. There's a submerged sense of melancholy in the strip that I'd be hard pressed to locate where it comes from; maybe it has something to do with the visual representations of the distance between cartoonist and reader, the empty last panel, and the narration's neutral tone.

Other strips are scathing comedic satires, like "Art School Confidential," with a relentless take-no-prisoners approach to art school, artistic foolishness, and self-deception: every panel is funny. To return to "Black Nylon" -- when I first read that story, I didn't know what to make of it. Now it seems funny to me in ways that I can't quite explain; it has no explicit gags (as other Clowes comics do), but there's a ridiculousness and over-the-top intensity to the superhero's self-deception and narration. The entire story seems like a very strange, very twisted "joke" -- yet it displays some real pathos, too, particularly in the ending scene. Along with conventionally recognizable comedic moments, Clowes's comics often employ an odd kind of humor in which you'll laugh at a panel but might not know why, or even if you should. This tonally complexity always makes a Clowes comic worth rereading; it often seems like a new comic each time.

SPURGEON: Does Wilson

change how we might see either the Rodger Young stories or Ghost World

? It could be seen as a response or in relation to that work fairly easily, almost to the point I'm mistrustful.

PARILLE: That's an interesting question I hadn't thought about. Wilson appears like an older version of Rodger in that he also wants a deep connection with other people but has a personality that puts this kind of relationship forever out of reach. While Rodger never voices his desires to others (only to the comic's readers), Wilson blurts them out to everyone, instantly alienating all potential friends. Yet Rodger's retrospective narration displays a self awareness that Wilson typically lacks.

And

Wilson's visual approach (Clowes draws each page in a different style, often in the look of a cartoonist who influenced him), makes that book, for me, fundamentally different. (

Wilson is also very linear, while "Blue Italian Shit" and Like a Weed, Joe" -- the two Rodger Young stories -- are not). But reading

Wilson as a response to these comics, as an outgrowth of earlier concerns, makes sense. While Clowes engages some similar issues in these comics, the same theme treated in such dissimilar ways almost makes it no longer the same theme, if that makes sense. This is true of the three superhero comics I talked about earlier.

SPURGEON: Why Modern Cartoonist

so late in the book? That seems in some ways like this evinces the core principles that you thought were important to open the book as opposed to an essay from yourself. What do you feel about reading Modern Cartoonist

now as opposed to when you first encountered it? I think it works extremely well in this context, but it didn't have the shock of the new that it had when I encountered it. How much is that a work of a working professional -- would you include it if it were about Clowes by not by him? What do you most appealing about his writing on comics and comics-making, what idea?

PARILLE: You're right that

Modern Cartoonist, in which Clowes discusses the cartooning history, reception, and practice, could have been placed where the opening interview excerpts are. But for people not immersed in comics, this manifesto might be a little dense to open with -- it's packed with references to comic book history. Since I wanted to talk about its unusual tone and provide many historical annotations, section three (on aesthetics) felt like the right place. It also works well as a companion to Darcy Sullivan's interview with Clowes on artistic process. Parts of

Modern Cartoonist examine the historical and conceptual side of cartooning, while Sullivan's piece explores the details of creating a comic: penciling, inking, lettering, and even drawing folds in clothing. I also think that readers are better prepared for

Modern Cartoonist after they've read all of the material that precedes it.

When I first read

Modern Cartoonist, it was a revelation, almost a "shock," as you said. It might have been the first extended piece of comics criticism (though I wouldn't have called it that then) I read. It seems even more valuable to me now as a way to think about comics and about what cartooning means to Clowes.

You asked if I "would you include it if it were about Clowes by not by him?" and I certainly would. But it's written in ways so unique to Clowes -- its odd sense of humor applied to a serious subject; its Freudian-inflected understanding of the cartoonist; a prose style that's simultaneously funny and apocalyptic -- that I can't imagine anyone else could write it. I wanted

Modern Cartoonist in the book because it has so much to say about Clowes's values and because it's so entertaining and well written. Clowes's look at cartooning through Freud's ideas about fetishes and his examinations of collaboration, world-making, and object-making offers the most interesting and useful ways to think about cartooning that I've ever read.

SPURGEON: I came out of this book hopeful not just for the sophistication of the approach but the level of the writing across the board. I know that we sometimes bemoan the lack of quality writing about comics, but I think that's because that gets defined in a way that's limited to a certain kind of book or to a certain point of engagement. Do you feel like this book is representative of the range of approach concerning comics, generally, or is this specific to Clowes? Are there are other Readers

to be published?

PARILLE: It's likely that, for the time being, there may not be as much quality writing on comics as we'd like simply because, when compared to something like film criticism, comics criticism is a fairly small world. But this has been changing. If we think back to what it was like in 2000, it's clear how much better it is now, with more academic journals, venues like

the new online Comics Journal, and the comics writing that appears in the

Los Angeles Review of Books among the many positive developments.

It's true that our ideas about what comics criticism should look like -- especially when it appears in books, magazine, and journals -- is often "limited to a certain kind... of engagement" that takes one of three or four modes, such as the review, profile, or analytical essay. I think

The Daniel Clowes Reader offers something a little different by using unfamiliar modes and by integrating so many examples of Clowes's art into the essays and talking about them at length.

Clowes's variety in terms of genres and styles as well as his highly allusive comics and broad engagement with contemporary culture makes his work especially suited to this kind of annotated critical edition. But its approach would certainly work for many other cartoonists. I'd like to see a book like this on Chris Ware, for example, and I hope to see more critical editions in the future; Alison Bechdel's

Fun Home, for example, is the kind of graphic novel that would work well in this format.

SPURGEON: What do you do next that's comics related? Is there a promotional cycle for this work? Is there a next work in mind?

PARILLE: I've been spending a lot of time getting the word out about the book, but assume the promotion will slow down at some point. As far as what's next, I'm not sure. I have been thinking about a few projects, but don't know if I will stay with any of them.

*****

*

The Daniel Clowes Reader, Daniel Clowes and Ken Parille, Fantagraphics, softcover, 360 pages, 9781606995891, 2013, $35.

*****

* cover to the new work

* a cover of

Tower Of Shadows, an early Parille favorite

* cover to

Lloyd Llewellyn #2, Parille's discovery of Clowes

* Clowes image I don't remember why I chose

* Enid and Rebecca

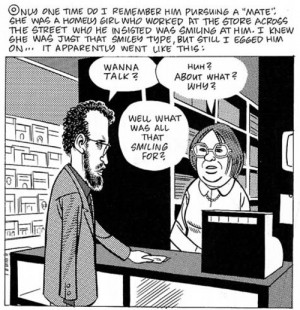

* from one of the Rodger Young stories

* photo of page of Alvin Buenaventura's design ganked from the Facebook page at Parille's invitation

* from "Black Nylon"

* pop culture-conscious illustration from Clowes

*

Ghost World-related art

* from "Ugly Girls"

* from "Just Another Day"

* from "Art School Confidential"

* from

Modern Cartoonist

* painting from cover of

Eightball; I just like that image (below)

*****

*****

*****

posted 10:00 pm PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives