July 13, 2013

CR Sunday Interview: Maris Wicks

CR Sunday Interview: Maris Wicks

*****

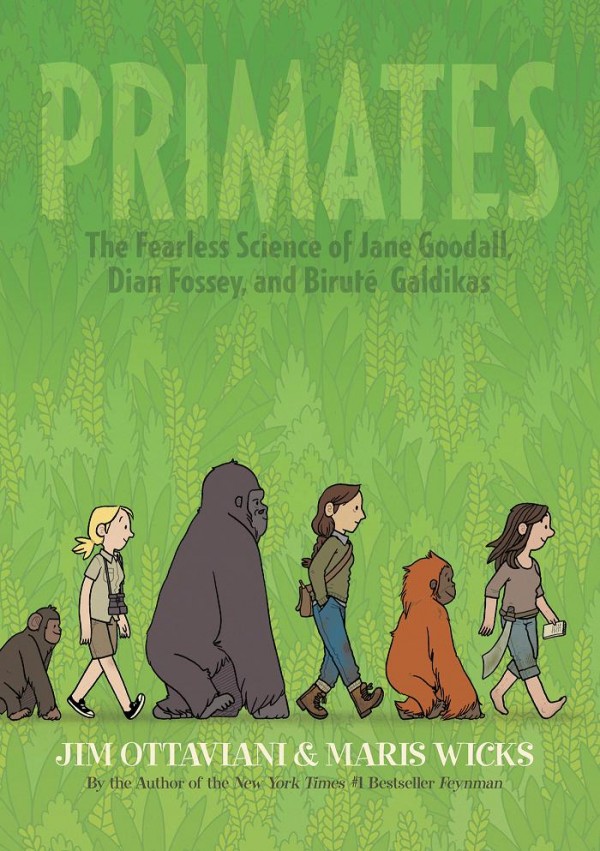

Maris Wicks is the artist behind the latest First Second effort in conjunction with comics-maker-about-science

Jim Ottaviani,

Primates. It's the story of three influential and widely-known field researchers in the area of primate studies:

Jane Goodall,

Dian Fossey and

Biruté Galdikas. Because of their shared experiences and through the patronage/instigation of

Louis Leakey, Ottaviani and Wicks blend the three very different stories into a broader saga about the costs and pleasures of practicing hands-on science. The New England-based Wicks lives with her partner of several years,

Joe Quinones, and their cat. She is working on a follow-up solo project with her current publisher, and has one of comics' more interesting day jobs – Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: Maris, I'm not sure how much I know about you. I'm reasonably familiar with your work. I remember that you were in Superior Showcase

, and I've seen some science-y mini-comics of yours. I'm totally unfamiliar with your background, however, as it pertains to comics. [Wicks laughs] I don't know that I know your origin story, where you came from, how you ended up doing comics that place so very high on the New York Times graphic novel bestseller's list. Is there a reasonably short version of your story, one that you might tell at a cocktail party?

MARIS WICKS: I can give you the

relatively short one. My degree, my undergraduate degree, is in illustration. I went to the

Rhode Island School Of Design. When I graduated in 2003, I was like, "I don't know if I want to do art." [laughs] I actually trained -- this is partly the long version, but I'll keep it short -- I trained to be an EMT. I thought I wanted to work on an ambulance. I observed for a while and I was like, "Fuck this. I can't do this. This is too stressful." [laughter]

I really liked education. I'd been teaching kids for my part-time jobs since -- summer camp stuff. I did a year of

AmeriCorps, which is basically governmental volunteer work. You get paid a living wage and an educational award to help pay off your loans or to put towards future education. I worked at a children's museum, and it was basically a year of working full-time for them and learning a lot about museum ed. I was like, "I like this like science as full-time stuff." I worked a bunch of environmental ed. stuff, and when I moved to Boston I ended up working for the aquarium: the

New England Aquarium, as an educator. So there's all this weird education stuff that I really liked because I liked teaching kids. But I didn't want to be a classroom teacher.

The whole while that was happening, I was doing minis and editorial stuff. The first big published thing was for

AdHouse. It was actually for

Project: Romantic. I liked minis, I was doing the zines not purely as a hobby, but I had a full-time education job because I need to pay the bills. The reality after graduating was like... yeah. I worked on a farm and did a bunch of weird stuff. [laughter] The first year of working at the aquarium I started doing more science-y minis, quick stuff. I was kind of like, "Oh, I want to do science comics. That's my 'dream'."

A year into working there, First Second approached me about submitting samples for the script for

Primates. I nearly pooped my pants because it was like, "This is what I want to do!" And it was less intimidating because it was written. I was still trying to build my confidence as a writer, so it was nice to be able to work with a script. Not only was it science-y, but Jim [Ottaviani] was one of my favorite writers in comics since I started going to

SPX and

MoCCA and things and learning about all of those wonderful things.

SPURGEON: What is it you like about Jim's writing?

WICKS: Bone Sharps was the first thing I picked up. I was actually a longtime fan of

Zander Cannon's. I read his stuff when I was 14 or 15. Most women I know got into comics... not through the back door, but through indy stuff. So I followed a lot of

Slave Labor. I always bought

Negative Burn. This is the mid- to late-'90s. I followed

Evan Dorkin. I didn't read a Batman book until college. I picked up

Batman: Year One and I was like, "Oh, this is really awesome." [laughter] I cut my teeth on all of that in my early twenties, which is actually a good way to do it.

When I picked that [

Bone Sharps] up, I loved the storytelling, I loved the way it jumped around, I loved the humor in it. I liked the way his dialogue was written. And I just love science. I made the choice to go to a full-time art college but I was torn. I really liked chem and bio and thought I might want to do that. But then I was like, "Oh, I really have to get a scholarship." It was a good choice. I felt like I abandoned science, but it came back in a different way.

SPURGEON: I imagine First Second's interest in pairing you up with Jim was due to your science-related mini-comics. But do you know why they had you try out rather than just offering you the gig? Was there something about what you were doing where they might not have known you wanted to do a long comic? Did they want to see something specific in the art? What do you remember about your tryout?

WICKS: They were basically like, "Submit what you want." It was very open-ended. There were a bunch of artists trying out for the book, and they said they would get back to us in a couple of weeks to a few months.

I thought they were looking for a good fit. I didn't have a track record of doing long-form work. I feel like that may have been the case. I thought maybe the content, but that was weird because First Second didn't know about any of my science education background until as recently as this past year.

SPURGEON: [laughs] Okay.

WICKS: When we started working on articles for

Primates they were like, "Oh, you're fairly well-versed in this stuff, especially when it comes to talking about conservation." I had been at the aquarium for almost six years. They are different fields, because I'm primarily marine bio, but I do know some of the language because my job is to talk to the public not just about animals but about ecology and habitat loss, all of these things that in the bigger picture are attached to primates and the primatologists' stories. It's weird that it's very organic. Or maybe I can just see the connections. But I didn't advertise myself as the science cartoonist.

I didn't know if I was going to get the book; I tried my hardest to turn around my samples in a week or two to be like, "Look, I can do this fast." The reality of the book was... not as fast. [laughter] When I started I was working full-time, but I eventually dropped my hours. Now I just work one day a week. I'm a weird, permanent part-timer. They've been great about being flexible with my hours at the aquarium to allow me to do art.

SPURGEON: The obvious thing that leaps out about your basic approach to the material is that you've employed a cartoony style, a simpler style than many in terms of the rendering and detail. Was there any apprehension or anxiety or your part about presenting First Second with that approach? I think it's distinctive and strong, but I can imagine some people going a different direction with this material. Did First Second have to be convinced at all that this style would work?

WICKS: That's something I thought about when I gave them the samples. I looked at pictures of each of the women, and Louis [Leakey], and the primates they studied. I was like, "I'm just going to give them my interpretation because anything other than that would not be honest to myself." If they like it, they like it, if they don't, if they want something more realistic, they don't. When they said yes, I was like, "That's awesome."

I don't think we explicitly had this conversation, but I was like, "Oh, this is cool. I get to draw this in my style." My thumbnails are really tight. My pencils are really tight -- for the submission process and for editing. But even preliminaries: I did model sheets for the characters at different ages because they show up at so many different ages throughout the book. There was no, "Draw them more realistically."

The way I draw resonates with me. I know that cartooning is sometimes seen as an ugly word in the world of illustration, but I proudly wave my cartoony flag because there's something nice about abstraction and the accessibility that the abstraction of cartooning allows, I think. I'm personally as a reader distracted when something is too realistic. As Jim says,

Primates is a real account but a fictionalized account. So it's kind of nice to be able to make it into a -- to see the world through cartoon-colored glasses. [laughs] It doesn't seem weird to me, but I didn't question it because I did rely so heavily on photo reference. I felt the honesty of trying to portray them my way was the undercurrent even though they're very abstracted.

SPURGEON: Was there anything you particularly enjoyed drawing in Primates

? Was there something that you got to draw that you knew would make for a good day at the drawing board?

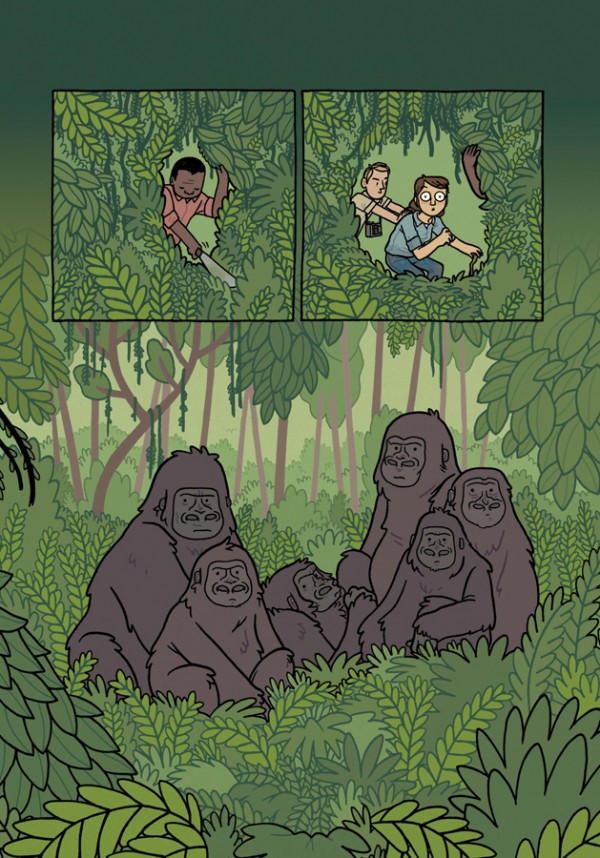

WICKS: My favorite part of the book -- and I know I'm not supposed to pick favorites -- was the last part, the Biruté Galdikas part. I really liked the jungle scenes. I got into drawing her foliage. I liked drawing her, and I liked drawing orangutans. "I like these ones; they're orange." [laughter] It was very basic.

Really the whole book was a pleasure to work on. Jim gave me a three-inch stack of photocopy references that he had compiled while he was doing research. So I was pretty well served. When he had a specific problem -- "There's a telephone on Leakey's desk; it's this phone" -- he would give me a picture of the phone on-line. It was helpful.

There were a few scenes, especially in Galdikas' part, that were in Indonesia where I could find pictures of the city but they were from the '80s and I couldn't find anyting prior to that. I was like, "Well, I'm going to draw this city minus all the weird '80s style cement buildings that are in it." So there was a little fudging on my behalf of trying to use photo references but use them appropriately. Taking an educated guess as to what to put there.

SPURGEON: Jim once wrote a little bit about his process, saying that when he gets art pages back from an artist, he puts aside his own script initially to look over what's going on on the page itself. Was there any back and forth between yourself and Jim apart from the formal editorial process? Were you getting feedback directly from him as you went along? Or was your primary relationship with his script?

WICKS: Jim was always in the loop when I submitted stuff; he was in the loop on the editorial process. From the inks to the colors there were a couple of jumping around changes -- rearranging panels and drawing a few new ones to help the flow of storytelling. When we were jumping between 20 years, sometimes it was a little choppy. So we ironed that part out. That was an active process with him and

Calista [Brill], who was our editor.

There's only one scene where I drew something that was not the way it was written in the script. There's a scene were Biruté and Rob, her ex-husband, are leaving for Borneo and they dash off-panel. I made them dash into the next panel holding a map and everything. Jim said, "I didn't mean for this to happen but it looks good. Happy accident." [laughter] There were some tiny, tiny minute things.

Jim and I are both big nerds, so when we did have conversations on the phone or over e-mail it was us nerding out. Not even

Primates stuff, just, "Oh this is exciting. Did you hear this science news?" [laughs] He was really good about sending me videos and articles, and I would do the same thing about

Primates-related stuff. I think there were even a couple about animal cognition, which we talked a little bit about. He had written a short thing about Biruté Galdikas in

Dignifying Science, the anthology he wrote about women scientists. So any time we had the chance, we would nerd out about stuff.

It was a relatively organic process. I really enjoyed it. Besides working with maybe a few editors and art directors on very rare occasions... it was a really awesome process with him and with First Second. Everything. The cover design even. It was all very fun.

SPURGEON: There was a scene late in the book, I think with Dian Fossey, where she pantomimes the hanging of poachers.

SPURGEON: There was a scene late in the book, I think with Dian Fossey, where she pantomimes the hanging of poachers.

WICKS: Yes.

SPURGEON: That scene was apparently redrawn; it was worked on a bit.

WICKS: We wanted to get that scene right. I can't remember... I did a couple of versions to make it fit the effect of what Jim wanted. I don't remember it being, "Oh no, this is horrible." It was just like trying it a few times. The end result was better than what I had originally tried to get the point across.

That scene is weird. It half makes me chuckle but it's also kind of creepy... I don't know. It's weird. She had a very specific personality. We talked about it at the beginning. Jim was like, "I'm not sure if it's okay, but she was a pretty heavy chain smoker. So anytime you want to throw in her smoking a cigarette, that's totally okay and it's part of her gruff, partly-jaded..." I mean, I didn't know her personally, but she seemed downtrodden yet somehow really passionate. I think it says in my research, and this may be in the book, that she felt more connected to gorillas than she did other human beings. There are parts of that that we wanted to get across -- her passion, but also her dissatisfaction, her frustration with human beings, especially in their treatment of these animals.

SPURGEON: I liked that there were off-putting moments in your portrayal of her. There were parts of the depiction that were unflattering, even unpleasant.

WICKS: Like tying up a poacher.

SPURGEON: That one stands out.

WICKS: I think that's a point worth mentioning. Whenever you have environmentalists, there is a fine line between what is acceptable and what is too far. Eco-terrorism might be an over-used word, but when does it become... ? It's hard. You have to look at the big picture. I get kind of defensive talking about stuff like this, but when is it all right to kind of break the rules? "Hey, people need to pay attention to this." And that might mean illegal things.

I think a terrible example of this is actually

Whale Wars, [laughs] that show about the guy that left Greenpeace and he funds his own boat and they attack Japanese whaling boats. I completely think that countries that bend the rules of the Marine Mammal Protection Act, that's not okay. But I don't think the solution... I don't think that's the right solution. I think there are ways that aren't negative ways to get across environmentalism and conservation. So it's something that I was thinking about in the background whether or not it comes across in the book. Based on my aquarium experience, I think about these things.

SPURGEON: One thing that connects the three women whose lives are detailed in Primates

is they're not exactly on track to do the kind of work they end up doing. They do go back and get degrees, but at the start there's a real lack of traditional credentials. I don't know that it's controversial for most people, but I'm sure it was controversial in that world. And you don't ignore that in the book, this element of dispute over the outsider aspects of the work they were doing. This is particularly true of Goodall and Fossey, that they were not initially credentialed the way other researchers might have been.

Do you have any thoughts on that element of the book? Because you're also doing what you're doing from a passion for it rather than as the next step on a credentialed path. Do you have any extra sympathy for the characters, that they fell in love with a certain kind of research, a way of working to which everything else then kind of caught up?

WICKS: Yeah. I think in the case of especially Goodall and Fossey, there were no women in that field to begin with. It would be almost unheard of. You went to school for science when you were a woman back then and you ended up being a science teacher or a nurse. That is what was happening in science fields for women. I'm not sure there was any other way for them to get into it.

Part of the refreshing thing for younger readers reading this is that yes, times have changed, and you go to school for this if you're going to be doing field research and data analysis. But all it took for them was passion and interest, and out of that passion and interest grew not just a career but a life... a lifestyle that changed them.

I totally understand where Leaky goes to Goodall, "If you want people to take you seriously, get your PhD. Go back to Cambridge." Which is so funny. Nowadays it's very, very different. You get your undergrad, and you get your masters, and then you do your doctoral stuff. The playing field is not level. There are a lot more women in science. There are more hoops to jump through -- not even more hoops to jump through: you just do it. Science is a limited field, and there are a lot of people going after these jobs. There are different standards for how to do it. But I think it was very worth mentioning that Goodall I think didn't even finish college before she was like, "I want to go to Africa." [laughter]

The work that they did... so much of science is data analysis and field research. What's sad to me is at the end, where Biruté is talking to another young PhD student and he's like, "Yeah, I can't wait to get done with this and I can get a nice tenure-track job." Oh. That's

sad. [laughter]

It's like that in every profession. There are teachers that are unhappy being teachers, and there are teachers that are really passionate and want to be there. I think you're going to find that in every profession. I liked that the women in that book are like, "I am doing my dream job and it is awesome and I want to do this the rest of my life." I feel like young people, more than ever, whether it's girls or guys, need to be inspired in science. I feel like it's the dark ages of science in that we teach it so that it's not fun after elementary school. I'm in elementary schools all the time for my job and I'm like, "Aw, middle-schoolers, why don't you like science? It's super-fun." They shut off, and in Mass. we focus on standardized testing like a lot of other states. But why shouldn't you like this stuff? It's awesome. [laughs]

SPURGEON: One of the other virtues of Primates

in the way that it presents these lives is that there's a deglamorizing of what they did. This takes place in the traditional way, where you see the struggles that each woman went through. But there's also a kind of a subtle portrayal of the amount of time they had to put in. The time spent to get these certain observations -- there's an honesty about the commitment level necessary to do this kind of work. I thought that a real strength of the book. Was it important to you to show these lives as lived? Do you think that's also important for young people to see?

WICKS: I got into the fact that they're outside and in the environment of the animals they're studying. A lot of times we tend to think of science as taking place in a laboratory or in a controlled setting. The quiet parts of the book also allowed other parts of the book to be louder. But I think that was valid to point out in the world we live in where everything is so convenient, and you get things now-now-now on the Internet, that data and good research means thousand of hours. There are aspects to things that we study or things that we do in our lifetimes that we're not going to be able to speed up, because that's not reality.

I don't want to discourage people from being scientists because they have to log 25,000 hours of research... [Spurgeon laughs] but I think it's refreshing. So much of growing up in the public school system you don't spend a lot of time outside. Since I've been in elementary schools, there's been a big shift in curriculums for elementary school kids. Instead of focusing on the rain forests or the coral reefs, a lot of what they learn first is about their backyards and their local habitats. Afterwards they learn about other ones and they can compare and contrast. I think that shift is really interesting. One, it creates good observations and critical thinking skills, because you're learning about stuff around you. Two, it helps to foster a connection to the place that you live whether it's an urban environment or a rural environment or coastal. I think that's something that's really interesting, that shift in curriculums. People really thinking about what's going to make the biggest impact, especially on elementary school age kids. I think that those two things are correlated.

Have you seen

the Look Around You videos? [laughs] I always think of that in my head... that's a parody, but I think that's important to mention in the book. It's funny because

Primates is about them doing fieldwork in exotic places around the world compared to where they grew up. It's still that fostering of caring, and being there, and being present. Again, sorry -- tangent.

SPURGEON: No, that's perfect for what we do. Now the color palette... was that left entirely up to you? Was that all you? Did Jim make any contribution to that? Can you talk a bit about selecting colors for the book?

SPURGEON: No, that's perfect for what we do. Now the color palette... was that left entirely up to you? Was that all you? Did Jim make any contribution to that? Can you talk a bit about selecting colors for the book?

WICKS: Jim's directions, and this was at the very beginning of the book, he had directions for the colors of the narration boxes and for the colors generally during each story. He said Goodall should be vibrant greens because she's fresh and young and the habitat she's working in is also vibrant greens. Fossey should be gray-green or a blue-gray green, just because her story is a bit more somber. The Borneo part of the story for Galdikas was to be saturated with yellow-greens and oranges for the thick jungle. Narration boxes, I think Jane's was a sandy color, Galdikas was a gray, and I think... I think Jane was blue, actually.

This was my first time coloring a large-scale print book. I sought coloring advice from

Alec Longstreth. He was the fellow that colored

Aaron Renier's Walker Bean story for First Second. I really liked his colors on that. He gave me a bunch of pointers about coloring in CMYK, about keeping black out of every color. So every single color you see in

Primates, there's no black. It's all consisting of Cyan, Magenta or Yellow. Alec expressed to me that you would get truer colors because it would not get muddied in the printing process because you would not be using any black. This actually happened. I had started coloring pages and sent them to First Second and they were like, "This is too muddy." And I was like, "Oh no, what do I do?" [Spurgeon laughs] I e-mailed Alec and I was like, "I need your Jedi wisdom, please." It was great. He gave me a few sample pages of

Walker Bean, and gave me a couple of paragraphs. It was invaluable. I've been meaning to make a blog post about the coloring process. There were hardly any tweaks that needed to be made after I started coloring that way.

It's weird. My partner Joe Quinones also works in comics. When he watches me color, he's like, "I hate how you do that." He colors in RGB and converts it. When I want to color I drop it and I open the color palette and then I basically make the black go away and then compensate in Cyan, Magenta and Yellow. He's just like, "I don't understand why you're doing that." I'm like, "But my colors, they come out okay." It gets very technical from a Photoshop standpoint.

I was very happy with the way the colors came out with the book. I was worried because I hadn't done much. I had done a book for

Tugboat Press, which was a kids' book. The colors were really muddy. Part of that was we did an organic printing process on that paper with non-toxic ink. Not that I don't think that should happen, because it's important to think about those things, but I think that was a lot harder to navigate. "Oh, it's so dark. What happened?"

SPURGEON: Wasn't Tugboat using a non-traditional comics printer, too?

WICKS: Yeah, he was trying to use a local... more environmentally friendly techniques. And it's weird, because we got proofs for that. The proofs looked nothing like the printed versions. Both Greg [Means] and I were like, "Aww..." [Spurgeon laughs]

It still worked out!

We just had a second printing on it, not through Tugboat but through Tanglewood Press, which does distribution for kids' books. That was part of the reason Greg Means at Tugboat got that one off the ground. He wanted to publish it in the hopes that it would get picked up by someone else -- which is not the way things usually work in publishing. But it ended up working, and it did well for the second publisher.

SPURGEON: The lettering in

SPURGEON: The lettering in Primates

-- were there also directives with an opportunity to play around with the execution? I don't even know that I noticed that each narrator was linked to a different text style until the scene where all three women were at a conference together and the lettering was placed right next to one another. Until then I was using visual clues to figure out who was talking and when. Once I noticed that the lettering itself was an indicator, I thought it a really nice effect.

WICKS: That was again part of Jim's direction. We talked about that really early on. When I sent him character sketches, with each character I lettered my recommendation of what their font should be based on the tone of the dialogue. First Second was like, "That's great."

I was also really stubborn and said, "I want to hand-letter this book." [laughs] I feel like I'm biased. In college I had

David Mazzucchelli as a professor and I remember him being like, "Hand-lettering is the best. Always hand-letter if you can." I was like, "Yes, yes, I must do that." [Spurgeon laughs] In retrospect, it was very hard for editing, later editing that happened. I would have to go back. It wasn't that long of book, but 130 pages of finding what needed to be changed, all of the lettering is 1200 dpi bitmaps on top of the art. It made it a little hard for me, but that was a sacrifice I was willing to make because I'm stubborn.

SPURGEON: Do you remember a quality of one of the women that led you to a specific conclusion about the font to use? What kind of factors were involved? How do you represent a personality in a font?

WICKS: With Jane, I picked a -- not benign -- but a very simple upper case/lower case. Again, she was the youngest of all three of them. Any time I could use cursive for her journal notes, I would. I feel like she was out there with nothing. She had a pen, and a lantern and some food. [laughs] Pen and paper. With Fossey, she had more cover. She had a cabin. She had cattle and dogs and chickens. Jim was explicit about her font being a messy typewriter font. I think I tried to match Courier as best as possible with a computer typewriter font. With Galdikas, I pretty much used my own handwriting. All caps. I feel a little more with her because she has her master's that it's clean science notes. Note taking in a legible handwriting way. Jane wasn't illegible, but she was British! I wanted her to have nice, cursive, handwritten notes. I wanted there to be a properness to her research. Not that there wasn't for Galdikas -- plus all caps would stand out from typewriter and from upper case/lower case. It would differentiate it. I think Leakey also got a pretty basic sans serif upper case/lower case; his wasn't too different from Jane's.

SPURGEON: You talked about roping Alec Longstreth in at one point, and we've discussed your relationship with Jim and with your editor. But seeing as this was such a long work for you and not something you'd attempted before, did you ever seek out outside feedback?

WICKS: The only other feedback I sought out on a regular basis was from my partner, Joe. We're in the same house and have been for ten years. We do go back and forth. It's like having a studio. I proofread his stuff; he proofreads my stuff. We give each other art direction. It's nice because he's a different set of eyes from indy comics -- it's not that he's seeing it through superhero eyes, but he's seeing it through a different lens.

SPURGEON: Superhero eyes might be helpful, actually.

WICKS: X-ray vision is pretty rad. [Spurgeon laughs] Other than that... I'm trying to think if there's anybody I gave preliminary stuff to. I don't think I did.

SPURGEON: Was there a way you coped with doing a longer project? Was there ever a dark night of the soul where you despaired finishing something of that size? Some folks says that step up in page count is really tough.

WICKS: I think one of the hardest parts was just trying to manage a non-comics job and doing comics. That meant that three days of the week I was at the aquarium and four days a week I was working on

Primates. If you do the math, that means no weekends. Which is a lifestyle I'm completely content with. I get to talk to you at 1:30 PM in my pajamas. I have no regrets. I've been awake since 8:30 doing work, but there's a casualness in place. Joe and I talk about this all the time, that it's hard to shut it off. We sort of want to keep working. You hit a stride at 2:30 in the morning and you're like, "I want to keep going. I'm having a good day." Granted the only thing we have to provide for other than us is our cat. I think things turn out a little differently when there's a tiny human being in the picture. So no. A lot of it was just patience.

Sometimes the editing would take a long time. I was very explicit when I set up my schedule -- which I didn't keep -- that we had a very open communication with First Second and I would re-evaluate after every major hurdle. After I finished the thumbnails -- which were super-tight, I almost did little scribbles to represent how many words I'd put in each caption and we're talking business-card sized drawings of each page -- I cleaned them up, scanned them, and sent them in. "If there's anything that stands out, I want to know now before I go to pencils." They have a lot of books on their plate. So a lot of time might pass in between. And it wasn't bad. I had other editorial small stuff going on. A lot of it was patience and being organic. Their mantra isn't the longer it takes the better but that if it needs extra time to be good, that's okay. Because the book had so much factual representation of places, and of characters, during the editing process I wanted to make sure there were no glaring problems. That meant looking at it with a lot of scrutiny. For Calista, who has a ton of other books, it had to be overwhelming.

I was really explicit about thumbnails getting the full editorial process, pencils same thing, inks same thing. Part of it was covering my butt, to prevent any huge edits that might happen later. There's a tiny bit of stuff that happened after the color proofs came out, stuff that we had to re-arrange, but really it wasn't a big deal. By streamlining the process and having those checkpoints, for me, and also for them, it made it go as efficiently as possible. Yeah, I'd love to be faster. I think every artist would love to be faster. But I never had a "I'm never going to finish" moment. I was like, "Persevere, get it done, be patient."

SPURGEON: I assume you're a different cartoonist now in some ways just for having that many more pages done. It seems like there's a point in the development of a career where cartoonists will change a bit with every hundred or two hundred pages. But are you different now in a way that's noticeable to you? Is there something you can do now that you couldn't before? Are you a more confident writer now for having worked that closely with a strip you enjoyed and admired?

WICKS: Confidence in writing was definitely built; I'll talk about that in a moment. But having a physical book and looking through it... I read

Primates a bunch of times, but I haven't read it since it came out officially. I read proofs in February. I kind of want to read it again. This past year was really hard because I finished it last April. Last May. So it's been a year. Waiting and waiting. "I can't wait until it comes out because it's been so long."

I totally respect the fact that First Second spends that full year. They warn you. "When it finishes, it's not coming out for a year." They put a lot of effort into PR. This one specifically they were barking up three trees. They were barking up the science tree, they were barking up the library tree, and the school tree. This book can fit neatly into any of those categories. It's cool that they did that. It's cool that we were reviewed in

Nature and in

Orion. We're also in the all-ages sectors and in the comics sector.

The other thing I did right after I finished

Primates is, "What am I going to work on next? I want to keep doing comics. I like this." So I put together a pitch for First Second and submitted that to them at the end of August last year. The book got approved, so the project I'm working on right now is

Human Body Theater, which is a 240-page comic book about the human body. So I think maybe there's a little bit of self-punishment there. "133 pages? Forget that. I'm doing 240 now." It's funny, when I asked them, I was like, "I'm just going to write this script; is there something I have to keep it under page-count wise?" And they were like, "No more than 240." I'm like, "Okay. I got that." [Spurgeon laughs]

The way that ended up working is I had talked with Jim. "You want to work again? I had a nice time working with you." I was throwing out ideas. He was like, "These ideas are great, but why don't you write them yourself." That extra kick in the pants was the confidence that I needed. "Oh. You think I'm an okay enough writer to do this."

I struggled in high school. I failed English one year. "I am failing my mother tongue. This is horrible." By the time I hit college I was like, "Oh. Hey. Writing is kind of cool." Because comics kind of combined words and pictures so neatly, that was kind of, "This is what works. This is how I feel comfortable telling a story." So fingers crossed that the new book I'm writing is okay. I have a wonderful editorial team and because it's the human body I'm going to have a consultant with a bunch of consonants after their name in the medical field to handle the factual stuff that it's tackling. That's how I've changed as a cartoonist and writer.

SPURGEON: You know, Maris, that's all I have. Did I miss anything you were dying to talk about?

WICKS: One other side project I think worth mentioning -- and this is another weird writing thing -- is that a year or two ago,

Mark Chiarello at

DC asked Joe Quinones and myself to pitch a

Batman: Black and White story. He asked the both of us for the story, but what Joe and I ended up doing is brainstorming and then I wrote the script and Joe did the art. So that was like never in a million years did I think I would ever get to write a

Batman story. They just announced that was coming out.

SPURGEON: That kind of brings it full circle for you.

WICKS: The reason why Mark asked is that he had all of my minis. Joe had worked with him before on

Wednesday Comics. He knew us as a couple, and I gave him my minis. "This is what I do." It was flattering that just through my mini-comics work, that was enough cred to be a writer.

I had a wonderful time. That story comes out in November, in either the first or second issue. I secretly love superheroes. And I wanted to work with Joe. We're collaborating on an

Adventure Time story as well. Just one of those background things that's like, "Oh, this will be fun."

*****

*

Primates: The Fearless Science of Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey, and Biruté Galdikas, Jim Ottaviani and Maris Wicks, First Second, hardcover, 144 pages, 9781596438651, 2013, $19.99.

*****

* the cover image

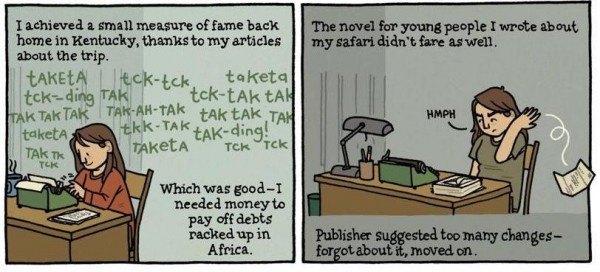

* the hanging sequence discussed

* one of the color pages

* some of the lettering in

Primates

* discovering the direction of one's life (bottom)

*****

*****

*****

posted 10:00 pm PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives