January 6, 2013

CR Holiday Interview #18—Sammy Harkham

CR Holiday Interview #18—Sammy Harkham

*****

I always have the best discussions face-to-face with the cartoonist

Sammy Harkham, which means the following interview likely doesn't work at all. I'll leave it up to you. It's old, too! I conducted it back before

Small Press Expo, so you'll forgive us both our hardened souls that had yet to be exposed to the at-least

ameliorative light of the very good small press convention season that followed our talk. I lost the tape, because I'm bad at my job -- and because I still use tapes. I found it during the course of this interview series because sometimes that happens. I hope that's okay. There were a few exchanges Harkham wanted excised that he communicated to me during the interview. I did so. The final edit is mine, as per a wish Harkham expressed at the end of our conversation. I edited solely for flow and hope that this interview captures not just Harkham on the various topics addressed but also the nature of our back and forth.

I first became aware of Sammy Harkham years and years ago at a

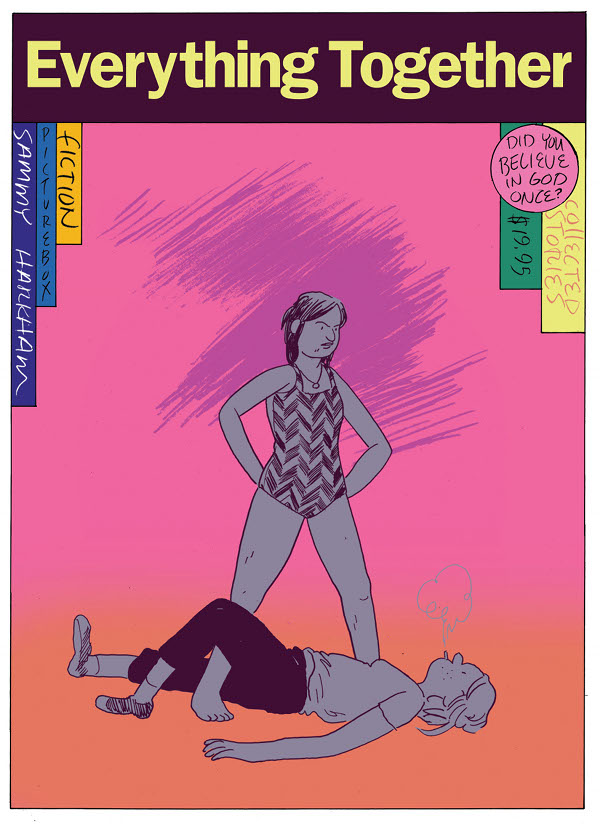

San Diego Comic-Con where he had set up to sell his work, work which at the time was more influence than influential. That's changed. Harkham has continued on with his primary creative outlet, the anthology

Kramers Ergot, to the point where it's one of the premier comics publications of our time. Its

eighth issue found its way into most people's hands at the beginning of 2012. The Fall's

Everything Together featured a variety of Harkham's own comics, both out of print and rarely seen. I'm particularly very fond of the short, biting humor strips as well as the longer piece about an academic suffering with writer's block, "The

New Yorker Story," that reads like a leap forward in the cartoonist's already-assured understanding of narrative. Heck, I liked pretty much all of it. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: Where am I talking to you today? Are you at work? Are you in your studio?

SAMMY HARKHAM: Basically, I've been working at my home for the last... two or three years? Time moves so fast now. It might be three years. 2009... I'm not sure exactly. I work from home, which is easier, but it's also getting to the point where I might switch it up and go back to work at the store.

SPURGEON: I visited you at one point a few years back and you were in a small studio space above the Family store, working with John Pham.

HARKHAM: It was useful at first because I wanted to get away from all of the distractions and I needed to finish

Crickets #3. I did the right thing, because I had solicited it through Diamond with Fantagraphics. The book was not even halfway done. [laughs] So that's the best way to say, "Let's just draw this. Let's get it done." You know? I'm always one of those people that's overly-optimistic about how long something will take. So I was like, "I'll get a page done every other day." It took longer.

I had become burnt out doing a lot of work for other people, so this was an opportunity to be selfish with my time. I turned this room into a mini-studio and I drew for like five months or six months straight. Which was fantastic. I think it yielded real results because of the consistency and full attention. But it's impossible to do now for more than a week at a time, because I have to do other work.

SPURGEON: That's a pretty traditional lament. Is there a positive to having those outside experiences?

HARKHAM: No. [Spurgeon laughs] The truth is you're going to have them. If you're a cartoonist that makes a living drawing comics, they're going to have outside projects that they want to do: curating a show, working on paintings, working on a movie. Whatever. They're going to do production art for a show. They're going to take the things that are different than their comics, maybe collaborative, that's the one thing you miss being so involved in comics. You miss the collaborative projects. I think you do those things anyway. It sucks to

have to do that work, when you want to finish your book or whatever that is. But it's a weird thing to complain about, because it's the usual complaint.

SPURGEON: I want to ask about the PictureBox book right up top. What made you want to do a collection now? Did Dan Nadel bring it to you? Did you go to him?

HARKHAM: I'll try to form an answer. I'm going to SPX, and I'm going to have people asking me about the book. So I'm going to have to figure out how to verbalize these answers. Basically... there's a part of you that gets depressed about all the work you've done. I realized the vast majority of things I've done are in comics that are hard to find. I'd done the

Poor Sailor book, and it had sold out, so even that was out of print. I thought, "Let's put all of this together, and make it an affordable, fairly casual collection." That was appealing. I didn't want it to become my focus for the year, didn't want it to become this huge production. It was appealing to me to make a book that felt almost like an annual. Like one of those Western annuals that you get.

SPURGEON: This is one of those questions I wonder if you'll roll your eyes at me for asking, but given the fact that you've put together so many book with a bunch of different people in it, did that inform how you work with your own comics?

HARKHAM: For sure. I developed an aesthetic sense for how I can make a book feel like a comic book. What's funny with this is, when I started thinking about a collection, just daydreaming about it, it was like, "Oh, this is like making an issue of

Kramers but with one person." You know? All of the sudden, it got exciting as an idea. As time passed, and I started working on

Kramers 8, I started to go in a completely opposite directions about the form of the book. BOOK in big, bold letters. The classic "book." What is a "book"? So

Kramers 8 was kind of taking the piss out of the whole idea of the literary book. So it was a little bit about adjusting my thinking, and figuring out how I wanted this to feel, even though lately I'd been getting excited about typset text and white end papers and things like that. [laughs] So it was like going back to repackaging something like a comic.

SPURGEON: It has this flexi-book look to it.

HARKHAM: I'm sorry?

SPURGEON: The cover is a softcover, but it looks like I could spill a drink on it.

HARKHAM: You can! The main influence is Japanese art books. A lot of Japanese magazines and art book have these really thick, thick dustjackets. They don't even score properly on the spine; they're rounded. I thought it would be nice to make a book that looks really different than the other books I've made and look really different from other books on the shelf. I liked the idea of a book that was brightly colored and shiny and looked like a product. I tried to carry that through. PictureBox gave me a synopsis of the book that runs in the inside dustjacket. There's a bio that PictureBox wrote as well. Normally I would throw those things out, and use those spaces for something else. There are quotes on the book, blurbs on the back. I wanted to have all of the elements of a traditional book, but hopefully play with it and make it interesting within that framework.

I hope that makes sense. You work on a book for a couple of months and you think you understand it, but when you actually try to talk about it, it's not the easiest thing to explain.

With the book, before anything else was decided on, I knew it was going to be a softcover book and it was going to have a dustjacket and I wanted it to feel like an annual or a magazine. I wanted the price point to be low, fairly low. I wanted it to be casual. I didn't want to trump up the work as "These are amazing comics that are part of the canon of literature." It's like, "These comics are out of print. I think they're good. [laughs] I want them to be in a handy volume." In my mind, before anything was formed, I was imagining a table at a comic book convention. Everything was there, all the new books are there, and this book looks almost wet because it's so glossy and the colors are so bright. That seemed like an exciting way to approach it.

SPURGEON: The arrangement of the stories inside, my impression reading the book is that the stories at the end of the book were increasingly dense. The narrative density of the works became more and more pronounced. Is that just your own progression as an artist, or was that purposeful in your arrangement here? Because it seems like right after Poor Sailor, it seems like your work becomes a lot more involved page to page. If nothing else, the majority of the time one spends reading this book is spent on the last 25 pages or so. I wondered if that was a purposeful thing.

HARKHAM: Not really. If I wanted to stick to that as a didactic, structural rule, I would have started the comic with

Poor Sailor or one-panel gags or something. But I did want the end of the book to feel like the sensibility was changing. The thing that happens, looking at all of this old work and me editing my own book like this, it's like looking at these stories for the first time in a long time the thing that's most striking -- this is very narcissistic -- is that you don't recognize the person that made the work. It was a little depressing in that way. I think I was a more hopeful person and a happier person when I was younger. And the work's not even that old. Most of it is from the last seven or eight years. To me the newer stuff, like "The

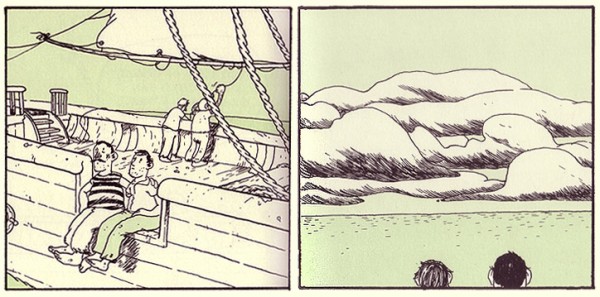

New Yorker Story," which ends the book, feels very different than

Poor Sailor or

Somersaulting. So my goal, as we went on, was to show that shift a little bit. So that when you get to the end, you're like okay, whatever book he does next will be more in line with the end of this book than the beginning of this book.

SPURGEON: I'm interested in that you're now worked with

SPURGEON: I'm interested in that you're now worked with Poor Sailor

a bunch of times. Did anything strike you about working with it this time? That's a work for which you're very well known.

HARKHAM: People really like that story. I still get mail about that story, which is cool. [pause] Nothing really, to be honest.

SPURGEON: [laughs] I was sort of surprised to see it in there, to tell you the truth. I wasn't aware it was out of print. That little hardcover works really well for that story, so I was surprised to see it again.

HARKHAM: I didn't feel like it deserved to be its own book. As the author. I'm not Edward Gorey. [Spurgeon laughs] I don't feel like my own drawings are so special they need to be individually showcased. The story to me wasn't so great that it needs to be its own object. I feel like this book -- it's probably going to be frustrating for the people that have the

Poor Sailor book. I wasn't really thinking about the people that have been reading me the last five years. I was thinking of the readers that are discovering, teenagers now, discovering my work now, as a way they can get my work in one form as opposed to tracking down old issues of

Crickets,

Vice,

Drawn And Quarterly Showcase, whatever. So I thought I'd put it in here. If you already had all of this stuff, you don't need it. [laughs] It's not lime I'm that prolific of a cartoonist, that I've done so much stuff... it's just a handful of things. But this way it's all together. And the way we reformatted it was just the way it ran in

Kramers 4 originally, which I've always liked.

SPURGEON: The stuff about about other cartoonists in here, material that gets blended in with some other observational work, that has to be an odd area... that has to be an odd subject to engage. On the one hand, it's all there for you. That's your life. You see other cartoonists. You have these experiences. At the same time, it's also a well trod-upon area, and it must be hard to do comics like that without settling on cliché: "Here I am with my cartoonist buddies." Is there a self-consciousness when you do strips like that. I think they're very well-observed, although I'm not sure how many people will be able to appreciate how much so. Is it tough to work in that very specific sub-genre?

SPURGEON: The stuff about about other cartoonists in here, material that gets blended in with some other observational work, that has to be an odd area... that has to be an odd subject to engage. On the one hand, it's all there for you. That's your life. You see other cartoonists. You have these experiences. At the same time, it's also a well trod-upon area, and it must be hard to do comics like that without settling on cliché: "Here I am with my cartoonist buddies." Is there a self-consciousness when you do strips like that. I think they're very well-observed, although I'm not sure how many people will be able to appreciate how much so. Is it tough to work in that very specific sub-genre?

HARKHAM: I think it's kind of fairly easy work to do, in that you're just making jokes about your friends. They're great warm-up exercise, in a way. Autobio, strips about your friends, I think there are holes you can fall into because that's very insular. That's what keeps me from doing more of them. If you go on a book tour with other cartoonists, there are loads of ridiculous things that happen that are funny to you and your friends and people that read comics. I was wondering if I should include that stuff because it's so insular. I thought they were so little, and that they kind of work on their own -- hopefully -- as autobio strips regardless if you know who the people involved are.

SPURGEON: There's an odd thing in comics, and in media in general, where it seems like you don't have a choice to not know at least a little bit about this stuff? It's almost like you're always... we follow Dan's work, and we also follow Dan. The majority of people that read Wilson

probably know at least something

about Dan, right?

HARKHAM: Maybe. I don't know. I'm not sure that's true at all.

SPURGEON: If the proportion I describe isn't accurate, that kind of reading relationship certainly exists as a construct within comics. That's certainly a

way people read them.

HARKHAM: To me that strip was just funny. It was a dream that Kevin had that he told me about. I thought it was funny. I'm sitting there months later just looking for something to draw... you know? I drew that in an afternoon and thought, "That's goofy." I don't know. The truth is, you could do loads of that stuff. I think. It's limited, it's very limited.

SPURGEON: There's not a lot of full color in here.

HARKHAM: No. I'm not a fan of full color.

SPURGEON: You're not a fan of color?

SPURGEON: You're not a fan of color?

HARKHAM: Yes. [laughs] I hate color. It's so disgusting. [laughter] I don't like

my work in full color. I think it makes the work look like it's trying to be more polished and more magazine-ready than it actually is. For the most part, I don't like it when other cartoonists do their work in full color, either. That's just a preference of mine. I prefer black and white or two-color.

The hardest thing to talk about is my work. I'd rather talk about the weather where you are in New Mexico. [laughs] I'd probably have more to say about the weather in New Mexico than this book.

SPURGEON: One thing that connects your longer stories is that many of them involve people in marriages, and in some ways, at least, what's going on in the story seems to encompass some sort of collection of thoughts or extended meditation on marriage. What is it about marriage that interests you as a subject for your comics? Your Kramers 8 story also deals with that kind of central life relationship, albeit in a more arch and depressing way.

HARKHAM: [laughs] It's probably just an automatic writer's response to "what's the setting/what's the world"? Because I'm married, that's the world. Every story that you read, the character has some sort of life. For me, the married world, it still yields so much as a setting, as a way to add even more tension and add more humor to a plot. I don't know if I've done a strip -- actually, I guess "Blood Of A Virgin" is explicitly about relationships. I feel like my other stories use marriage not as the center topic. A lot of this stuff... I don't write a script, I don't do a lot of pre-planning. I just sort of jump into it. So a lot of this is "first thought, best thought," at least initially. I guess there is a lot of marriage stuff.

There are cartoonists that are really good with every story jumping from genre to genre. Tone to tone. There are other people that just re-tell the same story over and over again, just in different ways. That's fine. Maybe I'm more like that. I don't know.

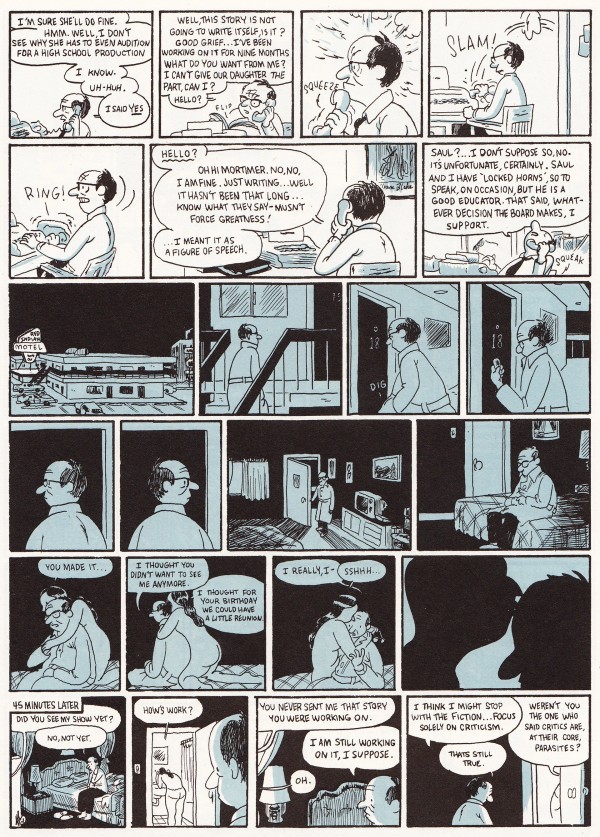

SPURGEON: We mentioned it in relation to how it was placed and the work's overall organizing principle, but "The New Yorker Story," the fact that it's very intense, page to page, very involved: I think it's six tiers, five or six panels across. Since you don't write beforehand, what led you to making that choice with that story? Why tell that story that way?

SPURGEON: We mentioned it in relation to how it was placed and the work's overall organizing principle, but "The New Yorker Story," the fact that it's very intense, page to page, very involved: I think it's six tiers, five or six panels across. Since you don't write beforehand, what led you to making that choice with that story? Why tell that story that way?

HARKHAM: With that story in particular, I was contacted by

Vice to do a strip for the magazine. They told me I had four pages. I didn't have a lot of time. I had something like two weeks. I hadn't drawn comics in a while, and the comics I was drawing were less panels to page and more realistic -- "realistic" -- looking. I took the

Vice gag. With something like that, you need to plan it out, so I wrote it out point by point as a story. It all had to come together quickly. I had to draw quickly. For me, when I make my panels smaller, and there are more panels on the page, it's easier for me to draw. It becomes more about pure information. It's about conveying the idea of a person typing at a desk in an office. When you only have two or three inches to do that in, it takes a lot the pressure off of making a nice drawing and just trying to make a readable drawing.

Doing that strip was a big revelation for me. Because I had a big time crunch, and I had to get it done. I found a mode of working that totally suited me. Working on that strip reminded me of how I like to make comics. I liked to spend one to days on a page. I don't like to be too fussy. It also reminded me of the kind of storytelling I like in film or in literatures. I have a preference for clean, declarative sentences, right? So if the comic can kind of mirror that, and I think that that one does in the sense that it's very unadorned and very straight-forward. Hopefully each panels gives you the information. As you work on that, you start realizing that emotional complexity doesn't necessarily come out of composition or realistic faces. A realistic face trying to convey sadness may not be as effective as two dots and a sad mouth. A downward line. Then you realize that whole idea that Chris Ware talked about in '97 in his

Journalinterview of comics as music, all of the sudden you understand what he's talking about in a whole new way, because it's not, if you look at each at each individual panel as notes of music, any individual note isn't necessarily complex, it's the arrangement of those notes that creates complexity. So working on "The

New Yorker Story" I started seeing that these were really simple images, really simple ideas, as individual panels. It's the arrangement of these panels, these really easy-to-read images, that creates -- hopefully -- something richer.

Then I realized, "Oh, Charles Willeford." It's totally the same, you know? Or Knut Hamsun. They state something, and they state it clearly, and that's no different than a perfectly round head with two dots for eyes and a downward line to show someone being sad. A writer like Charles Willeford, you couldn't pull out any line. You couldn't pluck one line out of any of his novels as an example of the complexity of his work, what makes his work so great. It's the reading of the entire book. To do that, to do that comic in those four pages in that many days, and have it turn out well, was a really good lesson. When I was done, I went right back into "Blood Of A Virgin," and even thought "Blood Of A Virgin" isn't as dense, I tried to use the lessons learned in that story. That's why the book ends with that strip, too, because I felt that was a big learning curve. There was a big learning curve with that story that I hope has influenced everything since. I think I was touching on those things, and those ideas, occasionally. But when you're constantly starting and stopping, where cartooning becomes a hobby because you have to have a day job and stuff, it's hard to have momentum and to keep the lessons learned. So that was a big learning experience for me.

SPURGEON: I want to ask you about Kramers

. I talked to you about Kramers

a tiny bit on-line this year, about four months after it had come out. My impression is that you were kind of mad about how it was received.

HARKHAM: No, no. Of course not. At this point, how could anyone making comics give a shit about how they're received? You know? I'm not 18 years old. I don't make a living doing this, not necessarily, so it's not... you make the work that you make, and you believe in it. I totally love the issue. As far as the reception for it? It never means anything, if people love something or not. I don't even know how you're supposed to gauge the response to a book. Do you gauge it on what people write you, or what you read? I read some reviews of

Kramers and it's the usual thing where I don't relate to anything they're saying. Occasionally you go, "Oh, wow. I hadn't thought about that." But it doesn't really ruin my day if somebody doesn't like

Kramers. You hope people like it.

SPURGEON: I thought that our conversation centered around that you thought people focused too much on the inclusion of the

SPURGEON: I thought that our conversation centered around that you thought people focused too much on the inclusion of the Wicked Wanda

material.

HARKHAM: Did we talk about this?

SPURGEON: I swear we did. My memory is really, really lousy now, but I think that's what happened. My impression is that you thought people didn't quite get why you included it, and you didn't know why people were making a deal of its inclusion.

HARKHAM: I mean, look. At the end of the day you include material that you like.

SPURGEON: Maybe that's the way to engage it, then. What did you like about that work?

HARKHAM: I think it's visually beautiful. It's not in print. I'd never really seen it before until I stumbled on it fairly recently. I liked it when I read it. I thought the writing was good, too. I wanted to make it feel a little separate from the rest of the book. That's why it's on glossy paper and it's at the end, past the epilogue. I felt the intentions and the whole approach to the work is very different from the approach of all the other artists in the books. I didn't want to say that, "

Wicked Wanda and the artists that made it are arm in arm with us in terms of how we approach comics and make comics." I still really liked it. I like it, still.

SPURGEON: It's a weird mix of approaches. There are some panels that are classic humor-comic -- it's a tableau where everyone is acting on a stage in front of you. Like everyone has been set up and it's an applause moment and we should all applaud now from the sheer delight of the new scene. There are also some cartoon-movement scenes. It's a strange, strange mix. I was taken with it, too.

HARKHAM: Did you find it tedious to read? I loved how dated it is, as well. There's a joy in reading jokes about Jimmy Carter. That's part of the charm of reading something like that now.

SPURGEON: That's a comics thing, too. I frequently read comics that I don't all the way understand in terms of who I might know that was reading them and enjoying them at the time they were published. I didn't understand Milton Caniff until my dad told me his sister, my Aunt Barbara, loved Terry And The Pirates. That gave me an in.

HARKHAM: I remember I went and saw an early Nicholas Ray movie, and the person presenting it said they were interested in it because it was the kind of movie their grandparents would go to. All our grandparents would go to. Then when the movie starts, you start thinking about it from that point of view. It can be helpful. To me it's as simple as if I like something, and it's a reprint of something, is it useful for people. Is it useful for me as a reader to have this stuff in print? I really like those comics a lot. I do.

SPURGEON: The other one that kind of killed me when I re-read it, that maybe didn't strike me as powerfully the first time was the Barbarian Bitch story.

SPURGEON: The other one that kind of killed me when I re-read it, that maybe didn't strike me as powerfully the first time was the Barbarian Bitch story.

HARKHAM: Anya Davidson. I think she's amazing. I think she's fantastic. She does great color comics.

SPURGEON: I think the color is very striking in that story.

HARKHAM: Her color sense is fantastic, I think. She's someone that's unique in comics in that her voice is really smart: I love how layered everything is. I love the drawing, too. She's amazing.

I love that whole book, actually. I'm really proud of that whole book.

SPURGEON: Is there a way to discuss the central mission of that issue at this late date. Was it that you wanted people to tell these genre stories?

HARKHAM: Whatever you start with, conceptually, definitely changes as you start working on the book. Working on a book is very similar to working on a story, if you're a writer. You have some ideas of where you want a story to go, and then it can take a left turn that you don't even realize. The story with this book? I was interested in making a book that sort of adhered to all of the rules of a book. A normal book. The vast majority of people that buy comics are getting them in bookstores, at least the kind of people that buy art comics or whatever you call them. So I thought let's do everything a normal book does, and let's even make it look generic in some ways. Let's invert it and play with it and take the piss out of it. So even having "Other Books By PictureBox" and white endpapers, to me those were fun ways to say, "This is not a unique book. This is not a special book. This is just a book. One of millions." Then hopefully when you start reading, it plays with your preconceptions. It has an introduction. It has a tipped-in artists section. When you get an issue of

Granta, there will often be a section of pictures of sculptures, or photographs. On different paper stock around the prose. I liked the idea of doing all of those things and hopefully doing them well and also kind of playing with it. How successful that is, I don't know. So much of making work is about process. I enjoyed the process of making the book. I learned a lot working on the book. That's the difficulty of talking about

Everything Together. I got what I needed out of doing those stories when I made them. To collect them and put them in a new book, it's a different experience than releasing a book of new material.

SPURGEON: We've talked about the satisfaction you get out of putting together projects like these. What is it that you think you're providing the artists with whom you work? How much of a concern is that it's interesting to them, or that they're shown off well?

HARKHAM: There's very little money to be made by contributing to an anthology. You're giving a lot of your time and a lot of your effort to something that doesn't pay you very well. I feel that people are only going to contribute if they really want to. To begin with. Hopefully by working with me, they enjoy the process of making that story, in a way that's different than making something for their own comics, or for their graphic novel, or whatever.

SPURGEON: I wonder if you don't have a pretty refined sense of this kind of thing. You've done some outside projects over the last few years, and I think you're an astute guy and you're a working artist that wants to work and place your own material in different places. Do you have a sense of what the rewards of something like that are?

HARKHAM: Yeah. I feel you should never do something because you think it might lead to something else. If I do something for a 'zine or anything, an anthology, I don't do it for "exposure," I do it because I like the 'zine and I like the people involved and I believe in it. Right now I'm doing a comic for Oily Comics, Charles Forsman's thing. He asked me. I like Chuck, and I like what he's doing and why not? I think I get ten cents for every copy sold. [Spurgeon laughs] I'm not doing it for monetary reasons, and I'm not doing it for exposure. I'm doing it because it seems like fun. I think fun is a really good reason to do stuff. That's how I approach something. If someone asks me to be in an anthology, it's a matter of do I have the time for this, do I have something in mind for this, and do I like the anthology itself. So I assume that people apply the same basic ideas for when I ask them.

SPURGEON: There was something you tweeted the other day that you thought that people go through too much hassle for too little reward.

SPURGEON: There was something you tweeted the other day that you thought that people go through too much hassle for too little reward.

HARKHAM: Oh, yeah. That's just being in comics now, for like ten years, which is fucking scary because I still feel like a tourist here. It's interesting watching how the world of alternative comics has changed since '99. I remember

David Boring and

Jimmy Corrigan coming out from Pantheon. You start seeing this mad rush of all these cartoonists start getting agents and start getting published by large publishing houses. You see how the vast majority of them are failures. Not as books -- failures as successful business enterprises. I don't understand why people who are happy with their small, independent publishers who let them do what they want to do, I don't understand why they opt to go somewhere else and make middlebrow work and fairly ugly books.

When I wrote that, I was jet-lagged [Spurgeon laughs] and I was getting feisty. It's interesting to see how companies change more and more. Where companies like PictureBox and First Second fit into it all. You know this; you've been in comics longer than I have. You can see... over the last eight years, publishers, all of those publishers lost on advances to books that didn't sell. Cartoonists lost because they had to work with publishers that didn't give a shit about them and tossed their books out as soon as they didn't do well on the first week or whatever. Then you go, "Who won?" Or "Who's winning?" The agents won because they got a big chunk of change for doing next to nothing and they got to sell a mediocre cartoonist to a publishing house that didn't know jack shit but knew they wanted the next

Fun Home or

Jimmy Corrigan or the next thing they can sell to a movie company.

Who wins? You hear so many horror stories of cartoonists who sign on with a major company, a major publishing house, and it doesn't make sense. [laughs] As comics become more and more like the rest of the publishing world, the only people that are going to become more successful with book sales are going to be people doing sports books, or sensationalistic autobio or political books. That's exactly the same as the regular book world. And that's fine. To me, it becomes a matter of embracing what it is. If you have a compulsion to draw comics, that's something you can't change. That's a fucked-up thing inside you. You're a talented writer and you're a talented artist, and you're now going to spend time making work that's barely going to be seen? You've got to own that, and embrace it and say, "Okay. This is what I do." It's for 500 people or less, or maybe a little bit more. But who cares? It seems... it's kind of ending now, but it seemed people were having these outsized expectations of what comics can give you. It's a niche thing. And that's cool.

SPURGEON: You think it had an effect on the work.

SPURGEON: You think it had an effect on the work.

HARKHAM: Maybe the work is fine because these cartoonists were middle-of-the-road anyway. They're just going to make middle-of-the-road work for everybody. But it's definitely bad that these are the ambassadors for comics. Are these the works that need to be front and center in bookstores? Probably not. If it were up to me,

Wally Gropius would be that book. But whatever. It's silly for me to even tweet about that stuff, because it's just me being goofy and running my mouth. That's never a good thing. And what do I know about any of this stuff? I just know from my own experiences and second hand from what my friends go through.

As I get older, I get more angry. I'm filled with more disappointment and more bitterness about life in general. The goal is to not let that take over your life. I love this interview that Zak Sally did with John Porcellino in the

Journal. It ends with him talking about his subscription list of 2000 people -- maybe it's less, maybe it's 800 people. And he's saying that that's a lot of people to be speaking to directly. I think that's great. I think that's fantastic.

I think you can save yourself a lot of heartache if you stop trying to turn this medium into something it can't be.

*****

*

Everything Together, Sammy Harkham, PictureBox, 120 pages, 9780985159504, October 2012, $19.95.

*

Sammy Harkham on Twitter

*****

* cover to collection

* photo from 2008

* from

Poor Sailor

* the cartoonist strip discussed

* Harkham in working in something less than full-color

* page from "The

New Yorker Story"

* from

Wicked Wanda

* from "Barbarian Bitch"

* two illustration pieces from Harkham, I believe both from 2012

* an earlier iteration of an image that's in the book (below)

*****

*****

*****

posted 4:00 am PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives