November 7, 2010

CR Sunday Interview: Sarah Glidden

CR Sunday Interview: Sarah Glidden

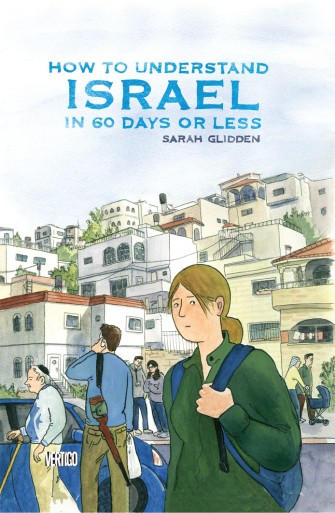

How To Understand Israel In 60 Days Or Less

How To Understand Israel In 60 Days Or Less is the book of the moment: a stand-alone graphic novel by a more-or-less first-time author (small-press cartoonist

Sarah Glidden, a former Maisie Kukoc Award Winner) from a major comics publisher (

DC's Vertigo imprint) with a fascinating narrative structure (

a birthright visit) performed in warm, easy-on-the-eyes colors.

As Glidden explains below, her book is less about the trip itself and more about the attempts we all make to come to some sort of understanding regarding complicated issues despite being bombarded by information from multiple sources and having to process everything from deep within our own preexisting biases and assumptions. In refusing to provide easy answers to the multiple questions raised, Glidden spreads her personal experiences both good and bad right out in front of readers in a way they either have to bring some sort of reason and analysis of their own to bear on the issues or close the book not having tried to understand a thing. It's a mature choice, and speaks well of both this effort and to the future possibility of more like it. I'm grateful for Sarah Glidden's time in what must be an extremely busy few weeks. -- Tom Spurgeon

*****

TOM SPURGEON: One thing that comes out of reading Understanding Israel is that there's no sense -- none that I noticed, anyway -- of you working on the project while having the experiences that facilitated the project. We don't see you draw or take notes or take photos for the comic book to come. When did this become something you wanted to put into comics form, and when you decided that, what kind of work did you have to do to capture this experience as faithfully as possible?

SARAH GLIDDEN: I knew I was going to make a comic about this before I went and I was pretty transparent about that at the time too. I even talked to the director of

Israel Experts (the tour provider) and let them know about what I was doing. Actually, I do have a handful of scenes in the book that show me taking notes and photos but the fact that you didn't notice them I guess says something about how I didn't make a point of showing that process.

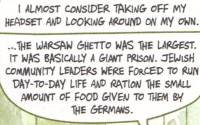

In real life I had this thick gray sketchbook that was glued to my hand the whole time. I brought it thinking that I was going to be doing a lot of sketching from life but I ended up just writing constantly. I wanted to get down everything that everyone was saying, especially the different speakers we went to see. Most of the monologues delivered by people in the book are pretty much verbatim (though edited) because I was jotting it down while they were talking. It was my way of getting my thoughts down on paper, working through confusion and emotions. The sketchbook also had all these notes I had taken before I left and other stuff so I could consult it as we went along. I pasted

the Balfour declaration in there, and

UN Resolution 242, and a pocket in the back with maps and Xeroxed passages from

Josephus. Basically, I was the weird nerd in the group and everyone knew it. But I don't think it would have added anything to the story if I had always drawn myself with a notebook in hand, writing. My character already comes off as kind of annoyingly over-eager and geeky; I think revealing more of the process might have made me unbearable. It would have taken the readers attention away from what the book is actually about.

SPURGEON:To sort of focus in on one aspect of that as a follow-up question, can you describe what you hoped to accomplish by turning this into a comics narrative? Is it important to you to get your personal experience down on paper, do you want to instigate discussion along the same lines of what you're thinking about during your visit, is there something about birthright visitation specifically that you're hoping to capture?

SPURGEON:To sort of focus in on one aspect of that as a follow-up question, can you describe what you hoped to accomplish by turning this into a comics narrative? Is it important to you to get your personal experience down on paper, do you want to instigate discussion along the same lines of what you're thinking about during your visit, is there something about birthright visitation specifically that you're hoping to capture?

GLIDDEN: When I decided to go on the trip I thought it was going to be a comic about Birthright and about how they would try to represent Israel to me. I had envisioned it as a sort of extended journal comic that I would just draw what happened and what we saw. That's the way I had approached comics up to that point: by making daily journal comics. But then the trip ended up being more intense on a personal level than I thought it was going to be.

It took me a few months of stewing after I got home to realize that this wasn't going to be a book about Birthright, it was a story about someone trying to learn how to think for them about something complicated. I hadn't realized that a lot of my opinions about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict were actually someone else's opinions that I had read somewhere and decided I agreed with because I trusted them to tell me the right way to feel. About halfway through the trip, I came to the conclusion that I couldn't trust anyone 100%, that no one was going to tell me what was the correct way to think about this situation that is so complex. That's a really terrifying realization and it made me feel incredibly isolated.

People talk about "keeping an open mind" as if it's some blissed-out path of least resistance, but I think sometimes, when you think you already know how you feel about an issue, it can be very painful and disruptive to open up to other possibilities. You have to admit that you might have been wrong about some things. But also, I had to weigh all of this against this fear that I was being manipulated.

I guess I wanted that to be relatable in some way. That kind of inner conflict can apply to anything. In the end I wanted to show that it's OK to be confused and no one is forcing you to choose a side. On the other hand, you can't really expect everyone to support your stance of confusion.

SPURGEON: Do you think your memory of this experience, or how you perceive it, is different now for your having turned it into art?

SPURGEON: Do you think your memory of this experience, or how you perceive it, is different now for your having turned it into art?

GLIDDEN: Probably. The fact is that I've been spending the past three years reliving two weeks. It was an important experience in the first place, but spending so much time thinking about it and writing about it has inflated it to the point where it's taken a pretty central role in my life. It's become less about the disparate things that happened and more about, well, what I think are the themes of the book. Maybe the actual experience has been entirely subsumed by the book version of it, which can never be a completely accurate retelling of the events as they occurred.

The way memory works, as I understand it, is that you are actually re-creating the experience every single time you reflect on it. It keeps morphing. But I wonder how writing memoir about a piece of your past changes that process. I haven't really thought about that. It could be really positive or maybe its kind of unhealthy. I'm not sure.

Anyway, there's something kind of indulgent and nice about being able to spend such a long period of time thinking about one thing, but I'm really glad I can move on now.

SPURGEON:I seem to remember that this started as a self-published project. Can you talk about how the book ended up at Vertigo?

SPURGEON:I seem to remember that this started as a self-published project. Can you talk about how the book ended up at Vertigo?

GLIDDEN: I was really surprised when Vertigo approached me and told me they were interested in publishing the book. I had been serializing the chapters as mini-comics, writing and drawing them one by one without having planned out the complete narrative. I had completed two chapters and was selling them at the

MoCCA fest at a table I was sharing with a bunch of other Brooklyn cartoonists when this guy with a DC badge that said "

Jon Vankin" walked over and picked them up and asked what they were about. If I had actually thought that DC might be interested in my work, I probably would have been a nervous wreck, but after he bought the comics and walked away one of my friends came back to the table and said, "Who was that?" and I was like "Meh, just some guy from DC," and didn't think about it anymore. [Spurgeon laughs] Then a few days later I got the e-mail that he was an editor at Vertigo and that they wanted to publish the book and I was totally bowled over.

SPURGEON: I know very few people that have done a stand-alone work with Vertigo; what was the experience like of making this book with their involvement? Was there a rigorous editorial process? Was there fruitful back and forth?

GLIDDEN: There's this assumption that if you go with a "big publisher" you're going to have to compromise your work, and I was worried about that at first with Vertigo. It was still too good to be true that someone was going to publish my book and actually pay me for it and that the trade-off would be my integrity or something. But that ended up being really off base. Jon gave me what felt like total freedom to shape the book the way I wanted while at the same time giving me great suggestions.

I think a good editor is someone who doesn't say, "I think you should change this" or "you have to cut this scene"; it's more like they help you step outside your own head long enough to see how what you're writing will come across to someone who isn't you. Then you know what you need to do to make the narrative better. Most of all, just knowing that he trusted me to make this whole book when I had never done anything longer than 25 pages made me feel like maybe I could actually pull it off. Because I really didn't know if I could.

SPURGEON: One of the best things about the book, I thought, was the coloring. Can you talk a bit about making this a full-color book, how you approached capturing the range of colors you did on the page, what was important to you in how that came out?

SPURGEON: One of the best things about the book, I thought, was the coloring. Can you talk a bit about making this a full-color book, how you approached capturing the range of colors you did on the page, what was important to you in how that came out?

GLIDDEN: I hadn't ever made comics in color before. Jon and

Karen Berger at Vertigo actually suggested that I color the whole thing. I said, "But I don't know how to color comics" and they said, "Sure you do, you made those stickers. Just do it like that." They were referring to these stickers I had made for the covers of the mini-comics which were just panels that I had colored in Photoshop. But coloring one panel to liven up your mini-comic's book design is really different than coloring a 200-page book.

So I just said, "Sure, I can do that" and decided that I would figure it out later. I had some time because I decided to pencil the whole thing first and at that point I also had the whole script to write so the coloring stage was over a year away.

As that time got closer I tried to learn more about computer coloring and started doing tests with a Wacom tablet and Photoshop but it just wasn't working. I hated everything about coloring that way and I wasn't good at it either. I was asking other cartoonists for help on the internet and Renee French asked why I wasn't trying watercolors. I hadn't considered this because watercolors have a reputation for being really difficult and unforgiving and I had only tried using them a few times with not so great results. But I got a lot of advice from the community and gave it another try.

What changed everything for me was using tube watercolors instead of the little brick kind. It was kind of a "duh" moment because honestly up until that point I had kind of forgotten that I was a painting major in art school. I had stopped painting pretty abruptly, turning to photography instead, and I think I had so successfully convinced myself that I was never going to paint again that it hadn't seemed like an option.

It had been about eight years since I picked up a brush, and applying watercolor is different than painting with oils, so I had a rocky start. But mixing colors on a palette was like getting back on a bike. I probably used the same seven colors to mix colors for this book that I had used in oils for painting landscapes and still-lives back in school and all that color theory stuff came back to me, too. Once I figured out my process, coloring the book became really relaxing and fun. I remembered that I used to love painting and that I had missed it.

SPURGEON: If you'll forgive me another craft question, did you hand letter the book? I really liked the quality of the lettering, how it was both attractive in a surface way but also seemed well suited to capture the succession of dialogues in the work.

SPURGEON: If you'll forgive me another craft question, did you hand letter the book? I really liked the quality of the lettering, how it was both attractive in a surface way but also seemed well suited to capture the succession of dialogues in the work.

GLIDDEN: I didn't actually letter the book. [Spurgeon laughs] Well, not directly, anyway. Vertigo wanted to get a letterer for the book -- which I actually didn't think was a bad idea. My lettering in the mini-comics was pretty cramped and not always legible and there's a lot of text in the book, so it was important that people actually be able to read it. But I really didn't want the lettering to look computery, either. Luckily, the letterer that they chose to work on the book,

Clem Robins, was really good. He made a font out of my handwriting by having me write all the characters five times and used a program that randomized them so the same "a" wouldn't appear twice in one word balloon. The human brain can pick up on patterns like that, but the way he did it you can't really tell its not hand-lettered. I was really happy with how it came out. He did the word balloons, too.

SPURGEON: One thing I thought was admirable in the book is how you put your doubts about your ability to process what you were seeing and learning right out there for us to see: a few times you suggest that you'd be better able to understand the issues involved if you'd seen a movie about them, you talk about misjudging certain people on the trip and you make a point of mentioning when you had a hard time connecting with certain people. How much anxiety did you feel about your ability to take in what you were seeing and communicate that to someone else? Did that ever get in the way of your making comics about it?

SPURGEON: One thing I thought was admirable in the book is how you put your doubts about your ability to process what you were seeing and learning right out there for us to see: a few times you suggest that you'd be better able to understand the issues involved if you'd seen a movie about them, you talk about misjudging certain people on the trip and you make a point of mentioning when you had a hard time connecting with certain people. How much anxiety did you feel about your ability to take in what you were seeing and communicate that to someone else? Did that ever get in the way of your making comics about it?

GLIDDEN: That difficulty processing things, misjudging people, trying to figure out whether I could trust what people were telling me, all of that was kind of what the book is about for me. There was just so much information being thrown at us at all times and at the same time I was comparing that to my previous knowledge, checking that against my notes and somehow at the same time trying to synthesize everything into something resembling a coherent point of view. I think at that point in the middle where I have a little nervous breakdown it was because I just got overloaded.

When it came to making comics about it, the difficult part was trying to get back into that place of confusion. I wanted to write it from the perspective of that moment, not from a place of hindsight and understanding. After a year or more of reflecting on the trip it was easier to understand why I was perplexed or why I had an emotional breakdown, but I really wanted the whole book to exist in the extreme present. My narrator isn't reflecting; she's reacting. So while writing about it I had to try hard to empathize with my past-self enough to write her experience.

SPURGEON: How do you think your relatively cosmopolitan set of experiences -- you've traveled, and we even see some of that late in the book, I take it you're educated, you're generally politically aware, and you're not uncomfortable simply being outside your everyday world -- had an effect on how you felt during this experience and then in making art about it? I'm not sure that I can express this as clearly as would be helpful, but I never got the feeling that I do with many travelogues that these were foreign experiences, that the novelty of what you were seeing or doing interfered with how you felt or what you saw.

SPURGEON: How do you think your relatively cosmopolitan set of experiences -- you've traveled, and we even see some of that late in the book, I take it you're educated, you're generally politically aware, and you're not uncomfortable simply being outside your everyday world -- had an effect on how you felt during this experience and then in making art about it? I'm not sure that I can express this as clearly as would be helpful, but I never got the feeling that I do with many travelogues that these were foreign experiences, that the novelty of what you were seeing or doing interfered with how you felt or what you saw.

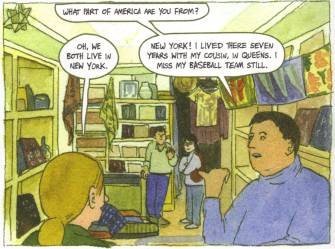

GLIDDEN: I think that novelty of being in a new place actually helps me focus on what I'm seeing and experiencing. This is maybe why I'll take any chance I can get to travel, and not just abroad but anywhere. You can learn almost as much by taking a day trip to the flea market in southern New Jersey as you can by going halfway across the world. It's really a cliché to say this but you learn the most about yourself when you travel.

Alain De Botton talks about this kind of thing in

The Art of Travel, saying that there's something about being in your everyday world that makes you more resistant to change. The furniture in your apartment doesn't change, so neither can you. Being in a strange place opens you up to things. You're not bound to your identity as much.

I don't think that having done a lot of travel makes me feel blasé about being in a new place. I'm still always really excited to see what things are different and what things are the same as my world at home. But with that excitement comes this very special brand of loneliness. It used to really bum me out to feel like I don't belong someplace. You're walking around, seeing groups of friends laughing and feeling comfortable in their surroundings and you feel so excluded from their happiness. Over time, though, I've come to understand that this loneliness is inevitable and not something to really feel badly about. So maybe the fact that I don't dwell on that anymore allows me to focus more on everything else I'm seeing or feeling.

SPURGEON: Why did you feel it was important to end the book you did, with a full chapter on your post-birthright trip experiences? What do you think -- or hope -- comes through by having that material included that might not have formed into shape had you ended the book a bit earlier?

SPURGEON: Why did you feel it was important to end the book you did, with a full chapter on your post-birthright trip experiences? What do you think -- or hope -- comes through by having that material included that might not have formed into shape had you ended the book a bit earlier?

GLIDDEN: This book for me was about so much more than just the Birthright trip, it was about trying to come to terms with how I felt about Israel and how I tied that to my own identity. And once the tour was over, it was even harder to try and wrestle with what that meant. During the tour, I had no choice where we went or even who I talked to, so all I had to do was take in whatever came my way and process that. That was difficult enough as it was, but once the tour was over I suddenly had to make decisions about how to continue exploring the issue outside of a set framework. That was frustrating and scary!

But of course, that's how life works. You have to choose what you're going to look at, where you are going to go, what risks you think are worth taking. I had an opportunity to go into the West Bank and I let myself get talked out of it because someone told me it was too risky. I really ended up regretting that. But being afraid and doing things you regret are a part of life and part of understanding your own approach to the world. So I guess I wanted to show that as much as things were difficult for me to come to terms with in the framework of a guided tour, that's just the start of it. Real freedom to explore yourself and your world is much scarier and doesn't have an end point.

*****

*

How To Understand Israel In 60 Days Or Less, Sarah Glidden, Vertigo, hardcover, 9781401222338 (ISBN13), 1401222331 (ISBN10), 208 pages, 2010, $24.99.

*****

* all art from the book being discussed except the fourth image, which is one of her mini-comics that kick-started that book

*****

*****

*****

posted 8:30 am PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives