August 4, 2007

CR Sunday Interview: Tom Neely

CR Sunday Interview: Tom Neely

*****

I was vaguely aware of

Tom Neely before

The Blot hit my desk, both as a cartoonist and an animator. What I've discovered since devouring Neely's debut graphic novel is that he splits time between animation, illustration, fine art and comics, with noticeable output in each area. That range of influences reveals itself in the

The Blot a meditation on intimacy, creativity and the loss of control over one's environment. It's a fine debut graphic novel, and one that hints at interesting work ahead, in whatever area he chooses to ply his trade. A personal aside: I also enjoyed the crap out of listening to a path to comics creation that was as much about school and training and figuring out how to express yourself as much as it is the objects of childhood affection.

The LA-based Neely was extremely helpful throughout the entire process of this talk, and I want to thank him for his time. He will be sharing a table with Sparkplug Comic Books at

TCAF and

SPX if you'd like to meet him personally or buy his book directly from him.

*****

TOM SPURGEON: Tell me a bit about your childhood, specifically as it relates to comics. It's my understanding that your interest in fine art and comics were both fostered fairly early on.

TOM SPURGEON: Tell me a bit about your childhood, specifically as it relates to comics. It's my understanding that your interest in fine art and comics were both fostered fairly early on.

TOM NEELY: I've been drawing as long as I can remember. My mom says I used to draw my

Star Wars action figures rather than play with them. I was a nerdy kid with so many allergies that I couldn't go out and play much, and was sick in bed a lot. So I spent a lot of that time reading books and comics all the time. I drew my first comic when I was six yrs old, and used to make stop-motion animated Super-8 movies with my toys.

My Mom was a housewife but also wrote a newspaper column about things for parents to do with their kids. I was the guinea pig for most of her crafty ideas, so we were always doing creative things like making puppets and costumes. My dad was a farmer and cattle breeder who turned into an English and Literature professor. He was always reading and introduced me to a lot of literature. My grandmother had an interest in art and had a lot of big art books in her house. She gave me a subscription to the

Mickey Mouse,

Scrooge and

Donald Duck comics as well as the

Smithsonian Book of Comic-Book Comics for my birthday when I was about 10 years old. Pretty soon I was obsessed with comics and that's all I wanted to do.

Even though I grew up in a the very small town of

Paris, Texas, my family traveled all the time. We went to Europe when I was very young and seeing those museums and castles made a big impression on me. I remember going to a lot of art museums when I was young. I was very fortunate to be exposed to many different things, and my parents were very encouraging of anything I wanted to do artistically.

SPURGEON: Can you talk about your schooling in San Francisco, the formal training you received and how you got there? Am I remembering right in that you're kind of ambivalent about art training?

SPURGEON: Can you talk about your schooling in San Francisco, the formal training you received and how you got there? Am I remembering right in that you're kind of ambivalent about art training?

NEELY: San Francisco seemed like a bad time while I was there, but in retrospect I think it was a really great experience for me. I went to

undergrad school in Tulsa, OK, which was only about three hours from where I grew up in Texas. That was a great school for me at the time, and I had some good teachers. I got my

BFA in painting with a double major in art education.

Then I started teaching at

Tulsa Community College and soon found out that I wasn't really comfortable with that -- most of my students were older than me. At the time I was doing very abstract work, large paintings with some collaged elements, kind of like

Rauschenberg or

Cy Twombly but not as good. I dreamt of going to New York and being the next Basquiat or something. I started applying to grad schools kind of blindly. I picked the top five art schools and applied to all of them. I ended up choosing the

San Francisco Art Institute because one of my professors from T.U. recommended it. If I did it all over again, I would have found out what schools had a strong painting program before making my decision, but I didn't know any better at the time.

When I got there, I was immediately faced with a student body and faculty that were largely against painting. I still remember the first day of orientation, having a group of "new genres" students say things like, "Why would anyone want do paint? Painting is dead!" and "I can't imagine why anyone would want to create an object that would hang on somebody's wall." I managed to meet a few painting students that I got along with, but I felt completely lost. I was in all these classes that taught us how to be conceptual assholes who don't produce any actual art, when all I wanted to do was learn how to be a better painter. It wasn't until my second year that I found a teacher,

Brett Reichman, who seemed to understand me and what I wanted to learn.

Around that time, I had sort of re-discovered my love of comics and defiantly decided to throw all the high-falutin' snobbery of my classmates back in their face by making oil paintings that were the equivalent of one-panel comic strips. A lot of those paintings were directly making fun of many of my fellow students and teachers. I got a lot out of art school, but what I got was completely different than what I originally wanted to go there for.

SPURGEON: How exactly did you rediscover comics, and how did that lead to your wanting to do some?

NEELY: Well, I always drew comics and read comics. Even when I was trying to paint like Cy Twombly, I was also drawing my own comics in my sketchbooks. I did this kind of autobiographical, humorous super-hero comic called

Tom-Man for a while. [Spurgeon laughs] Growing up in Texas, I had never read any indie or underground comics. I had never even heard of

Crumb until

the Zwigoff movie came out. I was still reading the

Spider-Man Clone Saga at the time. Obviously my knowledge of comics was very limited.

My first revelation was when I found an issue of

Renee French's Grit Bath in a quarter-bin at a comic shop in Tulsa. I thought it was the most amazing thing I'd ever seen. I actually made bootleg copies of it for my friends because I wanted more people to see it. Later, there was a local sci-fi convention that I attended because

Shannon Wheeler was going to do a panel discussion on self-publishing. That was the first time I'd ever heard of the concept of self-publishing.

Fast-forward to San Francisco: I started to find all these other alternative comics like

Chester Brown,

Chris Ware,

Dan Clowes,

Steve Weissman,

Seth, etc... Suddenly, I realized that anything could be a comic. To that point, I thought that you could do superheroes or you could do newspaper strips... I had gone the path of fine art and painting because I wanted to express something through my art that I didn't know was possible with comics. For the first time I realized that you could make a comic about anything, with any kind of style, and it could be as expressive and interesting as any great work of "fine" art. So, I started doing these paintings that involved this menagerie of anthropomorphic characters and making a comic book that told more of their story. I was able to combine both of these worlds in my own art, and it finally felt right. The comic, and the paintings, became an autobiography of my life in art school and in San Francisco.

For my

MFA thesis show, I had 50 oil paintings of these monkeys and bunnies and stuff, and along with it, I self-published my first comic book called

Aminals that starred the same characters. Somehow that impressed even the most conceptual of professors at my school, and even students who were attaching bubble-wrap to walls, and calling it art, seemed to like what I was doing. Basically, I got my MFA in painting by doing comics.

SPURGEON: Was your conception of what you wanted to do with comics when you started doing them again the same as it is now? If it's changed, why do you think your expectations are different?

NEELY:

NEELY: I've been through a lot of changes since I started doing comics. Right now, I'm more serious about it and I have a better understanding of what I'm doing as an artist, which has grown out of a lot of experimenting, a lot more reading and a lot more exposure to the indie comics world. I went to my first

San Diego Comic Con in 2000 (the year I graduated from SFAI) and saw that there was this whole world of people self-publishing their comics and selling them. I had a bunch of copies of

Aminals #1 and #2 in my backpack and gave them to every cartoonist I met. It was such an amazing thing to meet so many other cartoonists. I finally felt like I'd found "home" as an artist.

The year after that, I was offered half a table to share with

Martin Cendreda, and I made a new comic. At the time, I was working for Disney and was inspired to do a comic that reflected my love of old cartoons from the '20s and '30s. It got my foot in the door, and I met even more cartoonists and made a lot of friends in the industry. A lot of people bought those early comics and seemed to like them, but after doing three issues of it, I lost interest. It just didn't really work as a comic because I was trying to imitate animated cartoons and silent movies.

Sometimes I wish I could go back and erase those, but I learned a lot in the process of making mini-comics and going to lots of conventions and selling them and meeting a lot more cartoonists and learning from them. I hadn't found my own voice yet. I was having fun making funny animal comics, but I wasn't doing anything that expressed myself as an artist. But then around 2004 my art changed. That's when I started doing paintings in the Blot series and as that series of paintings grew, the comics followed and this book started to take shape.

I guess my expectations have changed in that when I started doing this seven years ago, I thought of it as something fun to do and not take too seriously... then somewhere along the way I realized that I was taking it seriously and started putting a lot more thought into it as my art. It's like I had this limbo period where I wasn't really putting myself into my artwork, but at the same time I was learning how to do it. Now, I feel like I'm doing something really good, but I feel like I have to convince people to forget my earlier immature attempts at comics and take my new work seriously.

SPURGEON: Can you talk in more detail about your various influences, particularly Floyd Gottfredson? Is there an influence we might not immediately see, or be surprised by?

SPURGEON: Can you talk in more detail about your various influences, particularly Floyd Gottfredson? Is there an influence we might not immediately see, or be surprised by?

NEELY: Floyd Gottfredson's

Mickey Mouse comics were probably the first comics I ever read when I was a kid. I read them constantly and studied them and copied them and learned a lot about drawing from them. I also had a subscription to the

Donald Duck and

Uncle Scrooge comics by

Carl Barks, but there was something about Gottfredson's stuff that was more attractive to me. There's something grittier and weirder about them with his approach to a panel and the kind of manic energy that is always present in all of his drawings. Carl Barks, though I love his work too, just seemed more subdued, a little more conservative. Later I got into superhero comics and was hooked. I really wanted to grow up to be the next great Spider-Man cartoonist.

By the time I reached high school, I was becoming more serious about art and comics didn't seem like the medium for me. I still loved drawing comics, but I started getting more into surrealism and began painting on canvas. My biggest influence from the surrealists is

Rene Magritte. Practically everything about Magritte fascinates me. He was one of the first painters I ever really connected with. His use of metaphor is still a big influence on my storytelling, though he always refused the idea that any of his symbols stood for anything other than their literal definition.

Philip Guston was probably one of the things that "saved" me in art school. I read several books about him and was inspired by the way he broke away from a successful career as an abstract expressionist and started doing his figurative cartoon-influenced work. That inspired me to break away from the pretentious bullshit of my art school surroundings and start making paintings of my comics. Through studying Guston's work, I learned about great old comic strips like

Krazy Kat and

Mutt & Jeff. I like old comics that have a bit of oddness, like

Bud Fisher's and

Billy DeBeck's.

I look through a big book of old comic strips and find myself randomly transfixed on a single panel where all you see is the foot of someone who has just walked out of the panel. That stuff kills me. I think it's the painter in me that likes to look at those panels as sort of abstract paintings, rather than something that serves a larger story. Actually, I think I read once that

Franz Kline sometimes drew inspiration for his abstract paintings from comic strips as well. Another, more recent influence was

Gene Byrne's Reg'lar Fellers. I found a collection of those a few years ago, and it wasn't long before more hatching and loose squiggly lines started to make their way into my work.

E. C. Segar's Popeye is another huge influence, but the Fleischer

Popeye animated cartoons have also influenced me, particularly in my animation work. Other inspirations, outside of comics, are painters like

Lucian Freud,

Egon Schielle,

Caravaggio,

Vermeer,

Honore Daumier,

L.S. Lowry,

James Ensor,

Otto Dix and

George Grosz.

I often like to make reference to artists in my work. Early in the Blot series of paintings, I did a piece designed after a painting by Lucien Freud, which inspired part of the first chapter of

The Blot and is drawn into the upper left panel of page 24. The first page of the chapter called "Broken" is inspired by

a Van Gogh drawing called Worn Out. I saw it last year at the

Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Van Gogh's paintings have never really blown me away, but his drawings are so beautiful I had tears in my eyes while seeing that show. I like making those little references as a little way of paying homage to the artists I love.

I think the work I'm doing post-

Blot is becoming less "Gottfredson." I'm mixing a little more realism into the cartoonyness. My line work is becoming more expressive. I think it's a result of absorbing my influences rather than imitating. It feels more natural now. I used to look at a lot of reference materials and other artists for how to draw things in that old style. Now I just draw things the way I draw them and it feel much better.

SPURGEON: You've mentioned a few times that a work like

SPURGEON: You've mentioned a few times that a work like The Blot

fits into an everyman-driven continuity that involves a number of other works, including fine arts painting. Can you talk a bit about how you came to that idea as the way to approach your work, and how that grander conception has an effect on the individual works like The Blot

?

NEELY: The "everyman" idea came as a result of frustration with the other characters I've used in the past. I had all these anthropomorphic characters that were, in various ways, self-portraits or stand-ins for my self. Those characters started taking on their own personalities and eventually became restrictive to work with. I wanted to create sort of a generic, nameless man that I could do anything with; a character that could represent me or anyone else. But when I started this series of paintings with him, something still felt stifled about the way I was working. That's when I started dropping ink on top of the paintings. I would finish one, lay it on the floor and drop ink on it Pollock-style to break myself away from the preciousness of constructing a picture. I wanted some kind of random, abstract, chance element to literally obliterate parts of the painting to liberate me from the rigidity of my normal painting process. Pretty soon, those ink blots began to take on a life of their own. They became a conceptual element within the paintings as well as a formal abstract element.

I approach each painting as if it needs to tell a story, or as if it's a part of a larger story. I want my paintings to have some sort of narrative element. After doing a lot of these, some of them started to feel connected, so I began writing a story around them. The process that has grown out of this is that the paintings serve as a space for me to freely express some stream-of-consciousness ideas without having to worry about the bigger picture. Then later, I come back and see if they work their way into the comics.

About a year ago I had reached a point where I had all of these short stories worked out that were based on paintings. When some difficult things happened in my personal life, I tied all those short stories together with some autobiographical elements, and that's what became the final book "The Blot." There are lots of paintings and ideas that didn't make it into this book, and may be a part of a future book. Vice-versa, there are parts of the comic that later become paintings. Ultimately I want the different works of painting and comics to inform and compliment each other as one large body of work.

SPURGEON: Tom, I know that you show in galleries, but I'm never sure that what means. How much of your living is tied into gallery work and illustration?

SPURGEON: Tom, I know that you show in galleries, but I'm never sure that what means. How much of your living is tied into gallery work and illustration?

NEELY: When I first graduated from SFAI I had a big show at a gallery in SF. It could've been the beginning of an art career, but at the time I was so burnt out on art that all I wanted to do was go get a job in animation and escape it all. In retrospect, I'm really glad that I escaped it, because I wasn't ready for a career as an artist yet. Now I am ready for that career and I've been trying to get back into the art scene, but that's a hard thing to do. I mainly show in smaller galleries and group shows that are more open to unknown artists. The bigger "fine arts" galleries won't pay attention to me because my work is too "cartoony." So, I often get lumped into the "low-brow" art scene, but I don't feel like I'm a part of that world of hot-rods and devil-girls. I feel like I'm caught between the two. I do shows pretty regularly and sell lots of paintings through the galleries I've worked with, but it only amounts to about 10% of my income because the smaller galleries can't sell work for as much. I tried to get work in illustration for a while, but I soon realized that it's just as difficult to break into that world as it is into the art world and chose to focus my attention on more fine art and comics. My bills are paid by working freelance in animation, online video games, and Japanese cell-phone animations for places like Disney and Nickelodeon.

SPURGEON: The stand-alone, credited animation I've seen from you seems very accomplished.

SPURGEON: The stand-alone, credited animation I've seen from you seems very accomplished.

NEELY: If you mean my

Muffs music video and

the Bush cartoon, I think they're somewhat accomplished and I'm very proud of them. But I see their flaws now and I think if I do more animation in the future I'll approach it differently.

SPURGEON: How has your work in animation been informative in an overall sense as to how you do comics?

NEELY: It was a weird jump from art school to a cubicle at Disney. But at the time, it was a refreshing change. Luckily, I had a friend who worked there and set up an interview for me. I moved to L.A. a week after graduating from SFAI and was very happy about that. But after two and a half years there, it didn't feel right anymore and I felt myself longing to devote more of my time to my own art and comics. That's when I left Disney to be a freelancer and spent more time painting and drawing. My time at Disney was almost like a second degree in commercial art after my fine arts degree. I learned everything about design and using computers from that job. I also think it improved my drawing skills by having to mimic all the different styles of Disney characters. One day I'd be drawing Mickey, the next day Cinderella, then Mulan, then Dalmations... and the style-guides are so strict that you have to really learn how to nail all the quirks of each different character. While working for Disney, I began to read more about

Walt Disney and studied his films extensively. If anything has really lingered from that, it's that I always want to put a strong emphasis on story in whatever I do, no matter how experimental I may try to be.

SPURGEON: Is there a reason you self-published instead of taking this to any number of publisher I'm sure would have been happy to work with you?

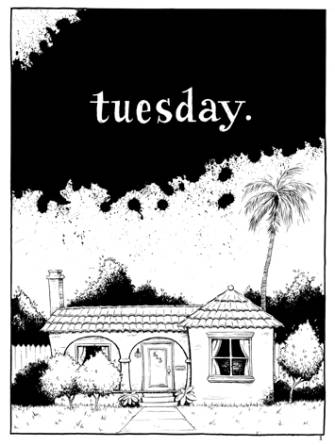

NEELY: In 2005 I self-published the first chapter, "Tuesday," as a mini-comic, released it through conventions in 2005 and then submitted it for a

Xeric. After it was rejected for the grant,

Top Shelf was interested. At first I really wanted to do the book with them, but when it got down to talking about book design and what they were willing to do with the printing, I started to feel like I was giving up control over this very personal work. This book is very connected to everything I'm doing as an artist now, and the thought of putting it in anyone else's hands just didn't feel right. That's when I decided to pull out of that and publish it myself.

Now that my house is full of boxes, I'm mildly regretful of that... but really I think for this book I had to do it myself. [Top Shelf's] Chris [Staros] and Brett [Warnock] were very cool about my decision and very supportive. I think it was the best thing, but ask me about that in three years when I'm still sitting on boxes and I might have changed my mind.

SPURGEON: Do you enjoy the publishing and promotional aspects of comics?

SPURGEON: Do you enjoy the publishing and promotional aspects of comics?

NEELY: I don't really enjoy the business end of publishing. I'm terrible with math and organizing spreadsheets and all that stuff. And I hate going to the post office to mail stuff, even though there's one just three blocks from my house. But I'm trying to make myself do that stuff and keep the books flowing out of here. In the future, I'm not sure whether I'll publish myself or look for someone else to do it. I like the idea of working with a publisher, but it would have to be the right relationship in which I felt comfortable with the amount of control I have over my work. As a self-publisher I have all the control, and I like that. But it would be nice if someone would handle all the business and the expenses.

SPURGEON: I don't want to get too deep into a discussion of the thematic aspects of The Blot

, because I think that people are probably going to be better off carving their own meaning out of the work. Let me ask this, though: Are there feelings about work or the nature of art or relationships that you deal with in The Blot

that have already changed since the time you did that work? Would The Blot

be different if you did it now?

NEELY: I have very personal ideas about what the work means, but I always hesitate to give anyone a defined meaning because I think, in some ways, that's the death of a work of art. I like working with strong symbols and metaphors, but I want them to be ambiguous enough to be interpreted in many ways.

My life has changed a lot since beginning this book. I started it during a very dark time, and it deals with a lot of that. The book was like therapy for me. Since then, everything has just continued to get better and better. I just got engaged and my life is much more peaceful and happy now. I think

The Blot would be different if I did it now. It had to have been made during last year to come out the way it did. And for that reason, I worked really hard to finish it all in one year while all those emotions were still fresh in my memory. I fear that my work might get boring now that I'm happy, but I don't think that will necessarily happen. My work has already evolved since I finished

The Blot. Though it's still a continuation of those characters and ideas, I think it's actually getting a bit weirder.

SPURGEON: You wrote what is a mostly silent book. You talked a bit about this earlier, but did the various vignettes exist independent of the work's through-line; did you develop them one by one? You use an awful lot of different approaches to page design in terms of your panel placement. How much did you have written when you approached a page?

SPURGEON: You wrote what is a mostly silent book. You talked a bit about this earlier, but did the various vignettes exist independent of the work's through-line; did you develop them one by one? You use an awful lot of different approaches to page design in terms of your panel placement. How much did you have written when you approached a page?

NEELY: Since my comics are an extension of my paintings, I think of them as silent. I like the ambiguous use of image over the more defined use of words in a narrative. But when writing the story I wanted the female character to have a voice. It gave her a disruptive power over the man that works as a guiding force but also shows her as a destructive intruder into this silent world.

A lot of the vignettes developed first as paintings. Then I started to write a story that strung those vignettes together. My ideas come to me in many different ways -- sometimes from a dream, sometimes from an actual event, sometimes just from my trying to work out a formal composition on a sheet of paper. I try not to over-think a painting. I think about it later to figure out what it is about and where it fits into the greater story. Once I figure that out, then I start writing it in my sketchbook. The first chapter was done independently back in 2005 -- the part I released as a mini-comic. The rest of it was all written around March and April of '06. I had the whole story arc figured out. Then I spent the next six months or so thinking about it. I did rough pencils of the entire book -- during this stage, I do any editing and page designing to make sure it all flows correctly. Then all the hard work is done and I get to enjoy the inking process. That took about two months.

I finished the whole book -- with the exception of Chapter One -- in just under a year.

SPURGEON: How important was panel to panel pacing for you in contrast to individual page design?

Neely: I think of those things as inseparable. I worked very hard to make the pages work together. I paid particular attention to where certain pages would happen. I tried to design pages that would fall next to each other as a pair, rather than individually. I used a lot of black pages to add a pause or space between moments -- like the waking point between dreams. I think the pacing is completely reliant on how I design the pages, and pacing is probably what I think about the most when I'm working out a story. When working with a silent comic, it's very important to try and slow down the reader so they get it all. It's very easy to read a wordless comic in a couple of minutes. I'm even guilty of often just flipping through and looking at the pictures quickly. But if you can find a way to slow the reader down and make them absorb it, then you can really get through to them.

I recently read

Destin by

Otto Nuckel and that is a book that only works if you spend a lot of time on each page, and then come back and re-read it a few times. I hope I achieved that kind of pacing, but it's hard to tell what other people will do with it.

SPURGEON: How did you achieve the wilder effects using the blot? Was that done directly on the page? Was control a factor in doing those sequences?

SPURGEON: How did you achieve the wilder effects using the blot? Was that done directly on the page? Was control a factor in doing those sequences?

NEELY: I've become very skilled at dropping ink on the page... It's all done directly on the pages. I finish a page, mask around the panels with tape, and I drop the ink on top of the art. There's always a chance that I'll screw it up completely and have to start over. I don't use any whiteout. The painter in me likes to see a finished presentable piece of art in the end. So all of my pages are just clean ink on paper. If I screw up, I'd rather start over than leave a visible correction. Luckily, I only had to redo three pages in this book. There are some places where the ink landed wrong, but I left it alone because I like that chance element to be a part of the book. A few of the pages where there is a "negative" white blot (like pages 138 & 139 or the girl's eyes in pages 152 & 156) are created by using Winsor Newton Art Masking Fluid, which is a rubber-cement like glue that's used in watercolor painting techniques. I would drop and spatter that stuff on the same way I would the regular ink blots, then paint ink over it, and when the masking rubber is removed it leaves a nice negative blot effect.

SPURGEON: Does living in Los Angeles inform your work at all? Is there such a thing as an LA artist?

SPURGEON: Does living in Los Angeles inform your work at all? Is there such a thing as an LA artist?

NEELY: I don't know how L.A. does or doesn't affect my art. There are an awful lot of artists in this city. But we're all so spread out, and if they're anything like me, they hate to drive across this city, so I don't see other L.A. cartoonists much.

A few years ago, I was feeling very isolated as an artist in this city, so I called up three other artists and proposed that we meet up once a month to drink a few beers and talk about art. We became an artist collective and called ourselves

the Igloo Tornado. It's me,

Levon Jihanian,

Gin Stevens and

Scot Nobles. We're all very different kinds of artists, but we're all at relatively the same stage in our careers and we all have similar goals. If you saw all of our art together, you wouldn't imagine we'd work together, but I think that's part of what has made us successful as a group. We all push each other to try new things, I know I've grown immensely as a result of that process. We had our first gallery show together last year and it was very successful. We have another one scheduled for February '08 and we hope to be able to put together some kind of book, too. I like a lot of other L. A. artists and cartoonists.

Souther [Salazar], for example, is one of my favorite contemporary artists right now. You'd think that with all the cartoonists in L.A. there'd be a big club where we'd all hang out. Maybe there is and I don't know about it, but I don't really have much connection to many artists outside of the Igloo.

SPURGEON: Do you think you'll do another long work like this one? Ideally, what are your future plans for comics?

SPURGEON: Do you think you'll do another long work like this one? Ideally, what are your future plans for comics?

NEELY: Yes. I want to do another long book. Right now, I'm working on a couple of series of paintings for my first solo art show. (my shameless plug: The show is called "Self Indulgent Werewolf" and will be at

Black Maria Gallery in Los Angeles opening September 15th.) There are three new series of paintings that sort of continue with the same main character from

The Blot. I'm doing a lot of stuff with werewolves. But at this stage, the story is still in the early part of the development. I don't really know where the story is going right now. It's sort of about evolving as an artist, but I've got so many ideas going in different directions I'm not really sure yet. I think I'll eventually figure out how to tie them all together to make my next book. I love making comics. I think this book is the best thing I've done as an artist so far. Making comics is harder than anything else I do, but holding that book in my hands now is a very satisfying feeling. Of course, seeing the boxes full of those books disappear would be even more satisfying.

*****

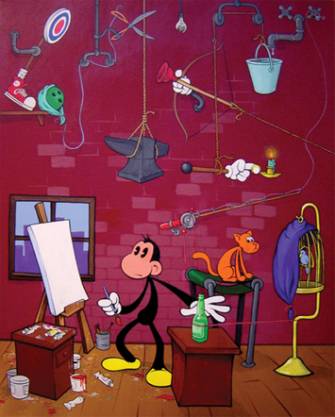

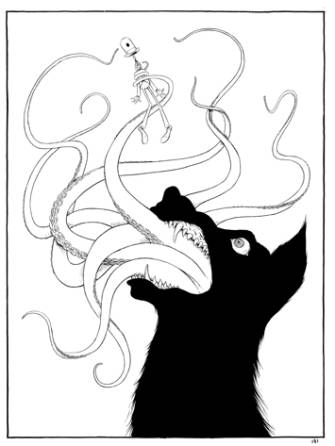

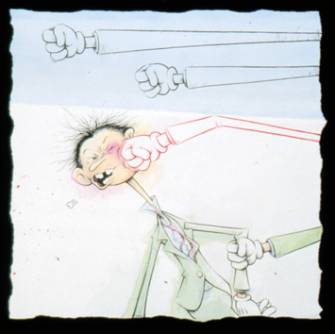

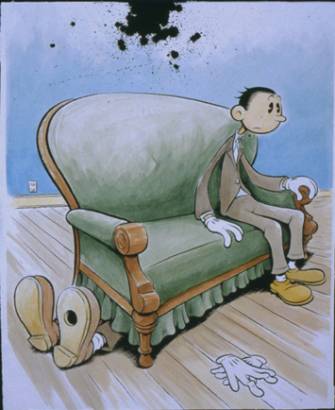

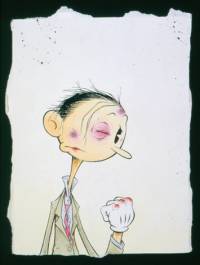

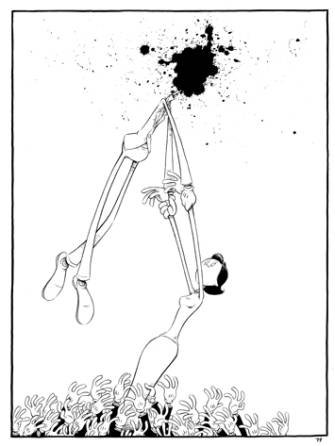

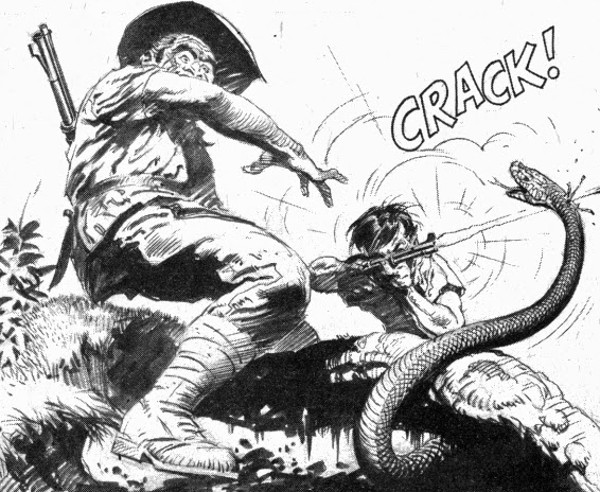

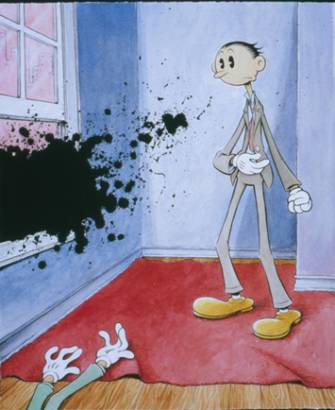

Art for this interview provided by the cartoonist. That's the cover to the new book up top. In general, the black and white pieces are the ones from

The Blot, while the color pieces are painting and other work. As the cartoonist says, a lot of the subject matter jumps back and forth between the exact same subject, and you can see similar characters and themes in different kinds of art. An

Aminals cover is also up there somewhere. That was Neely's first mini-comic.

*****

The Blot, Tom Neely,

I Will Destroy You, softcover, 192 pages, 9780974271583 (ISBN13), July 2007, $14.95.

*****

posted 10:30 pm PST

posted 10:30 pm PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives