March 30, 2014

David A. Trampier, 1954-2014

David A. Trampier, 1954-2014

David A. Trampier, a fantasy artist whose work was prominently featured in the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons gaming material in the late 1970s and a cartoonist who created the longtime featurey

Wormy for the magazine

Dragon,

died on March 24 in a nursing home in Carbondale, Illinois. He was 59 years old. The cause of death was believed to be have been a stroke; the artist had also recently been diagnosed with cancer.

Trampier was responsible for what may be

the iconic image in all of fantasy gaming: the cover art for the Player's Handbook volume of the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons series of books. The art depicted the aftermath of combat between an assembled group of adventurers and some lizard creatures: manly sword-wiping, sage plotting of the next maneuver, opportunistic looting of the space. Trampier was a house artist at gaming company TSR at the time of the publication of those books, which took the James Vance-flavored spin-off of tabletop war games out of several dozen campus gaming clubs and into the homes of a wide variety of young creative people, and in doing so, staked a claim to general cultural awareness.

It is important to note that in those days, when artwork of any kind had to be conveyed via published book rather than on-line, the pictorial component provided by artists like Trampier was a hugely significant element in the visualization necessary to make those games work. Trampier's work carried with it an ethos of grubby subsistance to a genre that often featured the lofty and heroic. His characters were frequently caught in moments right before or right after actual dramatic activity; they looked like people that would spend any money accrued in a seedy tavern rather than orienting themselves towards an apocalyptic battle of good versus evil. What action scenes Trampier did were usually of the random encounter variety rather than the table-thumping climaxes of the typical gaming evening. He drew a lot of hallways. Trampier's had a working class feel, the adventurer as everyman or everywoman.

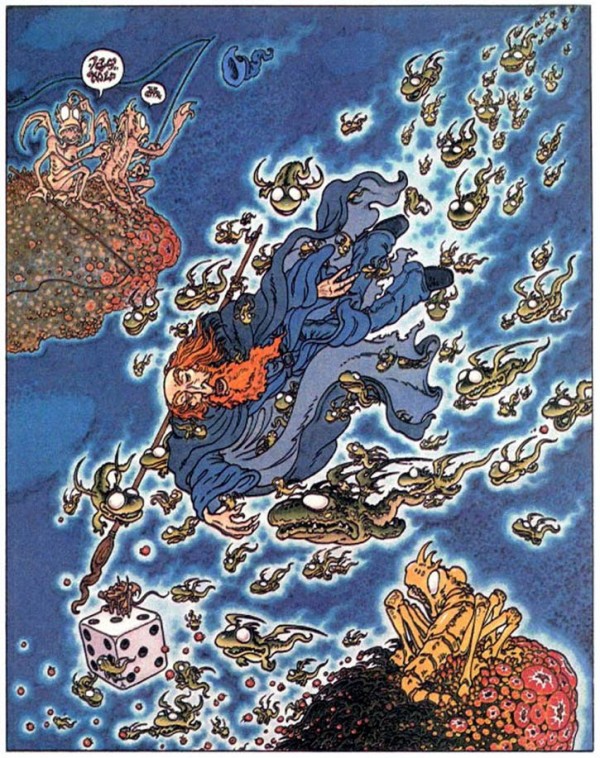

"Dave Trampier's art was easily one of my favourite things about Dungeons & Dragons," the cartoonist Dylan Horrocks told

CR, providing the jpeg at left of what he described as his favorite image of Trampier's. "It was his black & white drawings that I was most in awe of. I used to study his drawings closely: the great design sense, the gorgeous inking, the powerful solidity that made everything feel almost real. I tried to draw like him for ages, but of course I couldn't. His was such a distinctive unique voice - always recognisably him, even though he was so versatile. Sometimes he'd draw nothing but shadows, out of which some mysterious, half-hidden, genuinely terrifying monster would emerge. Other drawings looked like woodcuts, or delicate etchings. He could be funny, scary, epic or lyrical -- sometimes all at once. More importantly, his work often touched something deep in my brain. More than any other D&D artist, Trampier drew me into an imaginary world that seemed like a place I really wanted to be. Those little black and white drawings felt gutsy, charming, magical and -- somehow, in a weird way -- honest."

Trampier began a comic strip called

Wormy for the gaming magazine

Dragon starting in 1977, in that publication's devoted comics section alongside future prominent cartoonist as Phil Foglio. A brightly colored, rambling story whose central conceit was exploring these worlds from the monster's point of view,

Wormy was more reminiscent of a country-tinged Vaughn Bodé strips than any of the more realistically rendered, straight-faced comics that many fans might have preferred. More

Pogo than Pellucidar,

Wormy had to have been one of the odder achievements in comics at the time, across the course of a mini-boom of fantasy works that's only just now begin to come back into play. As was the case with many fantasy expressions of that time across various media, Dungeons & Dragons had an arch component that both expanded the game's appeal to a certain element of smart folks and older players that could not always take their fantasy 100 percent seriously;

Wormy certainly worked that way.

Wormy was also off-model in terms of the dominant Hildebrandt Brothers/Frank Frazetta/John Buscema art ethos of that time period, although its "serious" moments were as well-executed as nearly any comics fantasy going. One wonders if it isn't due for a bit of rediscovery given current publishing climes.

Wormy's run was truncated. In 1988, the feature and the artist disappeared; royalties and other payments to the artist were returned unopened. A few, idle rumors were floated in that pre-Internet era that there had been a dispute about the comic strip, a belief that firmed up a bit later on but may always remain a creature of second-hand testimony. In 2002, a newspaper article identified a person with Trampier's name as a cab driver in Carbondale; it was later confirmed to be the former gaming figure. Trampier declined invitations tendered for gaming-related work and appearances at shows.

An article at Paste suggests that Rampier was more recently considering a comics comeback, hoping an appearance at a local gaming convention might drive interest in publisher taking on a book featuring the

Wormy material. It's been further suggested that an element of financial need was driving that effort. He had in recent years sold original art after the closure of his taxicab service employer.

A significant storehouse of

Wormy material can be found

here. A Facebook fan page devoted to Trampier has a number of illustrations scanned in

here.

Horrocks: "I'm really sorry he seems to have had some tough times and I hope he found some peace in his later life."

posted 6:25 pm PST

posted 6:25 pm PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives