February 8, 2014

Morrie Turner, 1923-2014

Morrie Turner, 1923-2014

The newspaper comic strip cartoonist, illustrator and educator

Morrie Turner died on January 25 in Sacramento, California. He was 90 years old. Turner was the first African-American to see his work widely distributed to North American newspapers through traditional syndication strategies. His

Wee Pals was also the first such strip to employ a cast of characters from a wide variety of races and ethnicities. The cause of Turner's death was complications due to kidney disease,

according to a report in the New York Times quoting a family spokesperson.

Morris Turner was born in Oakland in 1923. He had three older siblings. His father was a Pullman porter, a secure job prized in the black community but one that took him away from his family for days and weeks at a time. The primary household presence was Turner's mother, who worked as a nurse and instilled in her children Christian values and faith that Turner would profess for the rest of his life. Turner grew up in West Oakland and went to school in ethnically and racially diverse classrooms he would recall when turning to newspaper strips decades later. He attended McClymonds High School and Berkeley High School. While he had no formal art training, it is believe he may have worked with some correspondence course materials as a young man.

Turner joined the Army Air Corps in World War II and served on the newspaper of the 332nd Fighter Group, better known as the Tuskegee Airmen (or even as the 477th Bombardment Group). His cartoon appeared in that newspaper and in

Stars And Stripes. The writer, cartoonist and curator Andrew Farago, currently employed at the Cartoon Art Museum, told

CR that like many veterans Turner rarely talked about his service, even one with the historical pedigree of the Airmen. "I knew him for ten years before he casually mentioned that in a panel discussion at the Museum of the African Diaspora in San Francisco a couple of years back," he said.

Turner married the former Letha Mae Harvey in 1946. Upon leaving the armed services, Turner would find a clerk's position with the Oakland police. He also began to freelance cartoon and provide illustrations to client. He built a list that included the

Saturday Evening Post and

Ebony. Turner became a friend of Charles Schulz, a solid, established presence in the newspapers and a rising star across all of pop culture. It was with Schulz's encouragement -- and rolodex -- that Turner began to develop a newspaper comic strip, in part to redress the lack of black characters on the page.

Wee Pals' other key foster-parent was the comedian Dick Gregory, whose own work and public profile was in the process of a significant transformation due to the cultural shift brought about by the 1960s. It's unknown why Turner worked for almost twenty years as a cartoonist before moving into syndication, but the result was a mature, fully-realized effort from day one.

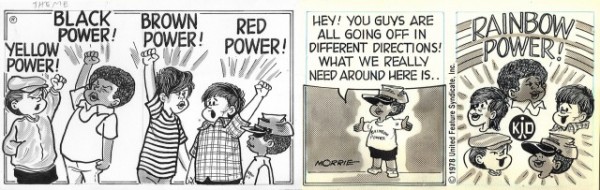

Wee Pals

Wee Pals focused on a set of childhood playmates like a few other prominent, past comic strip features. Unlike those features, the group readers encountered in

Wee Pals clearly racially and ethnically diverse: white, black, hispanic, asian, Jewish. The lead character was a black kid named Nipper, visually distinguished further by a Confederate cap that covered his eyes. Other characters were Jerry, Diz and Ralph, and the cast would eventually expand to include any number of kids defined only cynically by something other than their individual personalities. Despite its friends in high places -- Bil Keane named a character in his

Family Circus after Turner in 1967,

Wee Pals was at best a slow-builder and at worst a near non-starter.

Wee Pals only attracted a few client upon its debut from the Register and Tribune Syndicate in 1965. It wasn't until 1968 that a number of clients less than ten started to grow, in part because of that year's troubled political climate including the murder of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in the Spring. Legend has it by year's end that Turner's client list had swollen to over 100, certainly a sustainable number of several years moving forward.

Turner was one of a small number of National Cartoonist Society members to visit the troops in Vietnam. He and five other cartoonists spent almost a month there, visiting and drawing for the troops.

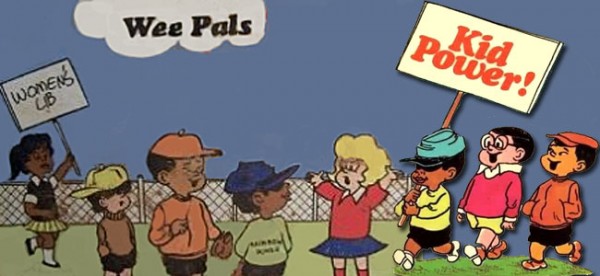

Wee Pals was the basis for the television cartoon

Kid Power, which came from Rankin Bass studio starting in September 1972. A live-action show, where kid actors playing the

Wee Pals took educational trips with their creator, started appearing on a San Francisco TV station that year and increased Turner's public standing in that community significantly.

Wee Pals remained a reasonably solid performer particularly in the 1970s, the last true decade of multiple-newspaper towns where a strip with a perceived potential audience advantage like

Wee Pals was a valuable commodity in distinguishing one paper from the other. The strip would add to its large cast through the years, becoming even more diverse. Turner became one of the few cartoonists of his era for whom it could be argued he was better known than his strip. He moved into children's books. The strip was collected into the paperback format that dominated the '60s and '70s, primarily through Signet Books.

One significant effect that Turner may have had on the Sunday newspaper page and in his animated work is that by featuring a cast with multiple children of color, all of whom were significant and recurring, a range of skin colors had to be used to depict them rather than a single, limited color employed to represent black skin.

Turner became a popular outreach and community-program arts educator in the Bay Area. "It's possible that every kid in Oakland from the 1970s through the 1990s saw Morrie speak at his school at least once," Andrew Farago told

CR. He spoke at schools, libraries, museums, conventions, anywhere he'd find a receptive audience that wanted to hear about his life and his art. Even when his health started declining in recent years, he barely scaled back on his public appearances."

In a lengthy, lovely appreciation, the artist Jimmie Robinson noted the effect that Turner's example and presence could have on young, black artists.

"I was in a school for the arts. It was a magnet education/arts program in Oakland, California called Mosswood Arts. So it wasn't uncommon for the school to have various artists come in and speak to the students. However, when Morrie Turner came to visit there was something different. And for me it was that Mr. Turner was black. In fact, in my three years at that art school he was the only black adult artist I ever met."

In later years the key role Turner's strip played on the comics page in terms of diversifying its content made him the subject of lengthy profiles and appreciations. He would eventually move his strip to Creators Syndicate and it has remained in syndication, with likely only a handful of clients, including the

Oakland Tribune.

Wee Pals was still Turner's work, with a shakier line and increasingly loose lettering, but boasting the same emphases as years and decades past. One of the things that Turner did that may have been unique to

Wee Pals was turning over the strip to an historical person or high-achieving living personality without needing the spur of a special holiday or week to do so. Farago told

CR that Turner may have been ready to once again consider full retirement once

Wee Pals had hit its 50th year in 2015.

Turner received the Milton Caniff Lifetime Achievement Award in 2003 from the National Cartoonist Society. He also received the Anti-Defamation League's Humanitarian Award, the Boys and Girls Club Image Award, the B'Nai B'rith Humanitarian Award, the California Educators Award, an Inkpot Award from the San Diego Comic-Con, the Brotherhood Award from the National Conference Of Christians And Jews, awards from the American Red Cross and the NAACP, and the California Black Chamber of Commerce Lifetime Achievement Award. In 2000, the Cartoon Art Museum presented Turner with the Sparky Award named after his friend Charles Schulz. In 2012, Turner won the Bob Clampett Humanitarian Award, which he accepted in front of an admiring crowd at the Eisner Awards ceremony. A documentary on Turner's life through the prism of his religious beliefs,

Keeping the Faith with Morrie, was released in 2001, and Turner was one of the cartoonists feature in 1980's

The Fantastic Funnies. A major retrospective of Turner's work was hosted in San Francisco's main library marking the 45th year of

Wee Pals.

In addition to his professional, educational and community work, Turner also in his later years became an active member of the Center For Spiritual Awareness in West Sacramento. He was also on

the advisory board at Cartoon Art Museum.

Turner is survived by a son and namesake, four grandchildren and a companion, Karol Trachtenburg. He was preceded in death by wife Leatha in 1994.

posted 5:00 pm PST

posted 5:00 pm PST |

Permalink

Daily Blog Archives

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

Full Archives